Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019)

Más datosTo determine the effect of behavioral interventions on improving the severity of post-stroke insomnia.

MethodThe design of this study was observational research with a consecutive sampling method consisting of intervention and control groups 12 people each. This research was conducted for two months, April–May 2019, at Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital and its network. Patients were given a 30-min behavioral intervention. Insomnia severity was measured by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) before and after an intervention.

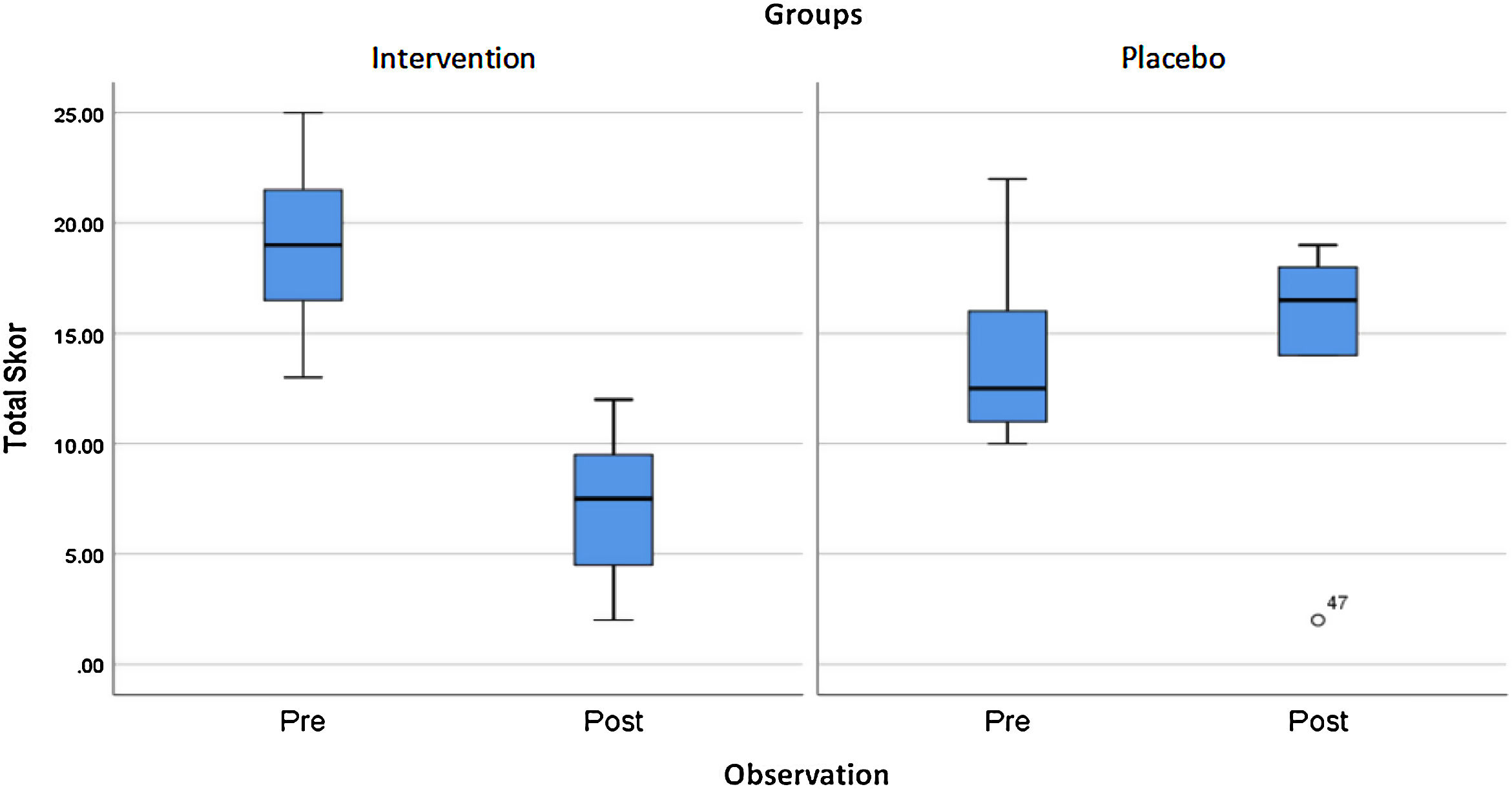

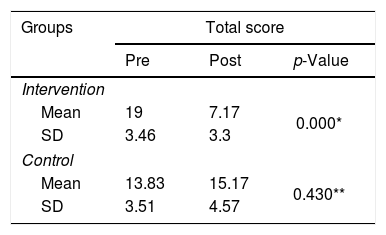

ResultsThere was a significant decrease in the ISI score intervention group (p<0.001), where the mean of ISI score before and after the intervention was 19±3.46 and 7.17±3.30, respectively. Moreover, for the control group (p=0.043), the mean of ISI is 13.83±3.51 and 15.17±4.57 after two weeks of follow-up. There was a significant decrease of ISI scores in the intervention group compared to controls (p<0.001).

ConclusionBehavioral intervention has a significant effect on improving the severity of post-stroke insomnia.

Stroke is an acute situation caused by a temporary or permanent brain. The primary division of the stroke is following the underlying pathological process, distinguished by bleeding and ischemic stroke. A stroke occurs in 70–85% of cases, and strokes develop because of the inability to supply oxygen to brain tissue and due to blood clots. While bleeding strokes constitute 15–20% of cases and can cause mass effects on the brain. One of the most common complications of stroke involving sleep problems, stroke patients obtained 76.8% of sleep disorders and 82.5% of patients with bleeding stroke.1

Sleep disorders, as a neurophysiological disorder, occupy a significant incidence in stroke patients. Sleep disorders often occur in stroke patients in the form of sleep apnea, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness. Sleep disturbances significantly reduce the quality of life of patients. From one study, data obtained that the frequency of sleep disturbances in patients did not depend on the location of the lesion. Statistically, there were no significant differences in the incidence of ischemic stroke and bleeding patients.1

Stroke can further aggravate sleep disorders or caused by strokes. Unrecognized and untreated sleep disorders can affect rehabilitation efforts and poor functional outcomes after a stroke. This risk increases stroke recurrence, thereby increasing alertness and screening for sleep disturbances significant in preventing primary and secondary strokes, and in improving stroke outcomes.2

One of the most sleep disorders in stroke patients is insomnia. The prevalence of insomnia in stroke patients in the form of complaints is difficult to start sleeping around 23–40% and maintain sleep 57%. Insomnia patients are typical in women compared to men in patients without strokes, and in older people ≥65 years, are not satisfied with their sleep quality compared to younger ones. Data is obtained that 48% of stroke patients and more than 80% of insomniacs use sleeping pills. Other sources say that insomnia patients have a history of depression and anxiety disorders (30%) compared to patients who do not have insomnia.3

Insomnia in stroke patients usually occurs in dominant major strokes, especially in those with more severe neurological symptoms. Patients with complaints of being unable to walk. It showed more sleep disorders than those who did not.3,4 Insomnia is defined as difficulty in starting, maintaining sleep almost every night for a certain period with sleepiness during the day. According to the Psychosocial Outcome in Stroke (Poise) Study, 30–37% of insomnia occurs in the first year.4 In the first month after the stroke, the prevalence of insomnia is around 50%.5 In a meta-analysis study found that short sleep, ≤5–6h/night, was an independent predictor of the incidence of stroke after adjusting for age, gender, vascular risk factors, and comorbidity. In a meta-analysis study, it was found that short sleep, ≤5–6h/night, was an independent predictor of the incidence of stroke after adjusting for age, sex, vascular risk factors, and comorbidity.5

In a meta-analysis study, it was found that short sleep, ≤5–6h/night, was an independent predictor of the incidence of stroke after adjusted for age, sex, vascular risk factors, and comorbidities.5,6

Complaints of insomnia are established if patient reports: (1) difficulty to fall asleep (at least for 1h), (2) insomnia at night (at least for 1h), (3) waking up at the beginning of sleep time (at least for 1h), (4) poor sleep quality, and (5) use of the sedative agent for sleeping during the week they could fall asleep, even if given enough sleep opportunities.2,3 The diagnosis of insomnia is established if there is a functional disorder during the day, including fatigue, daytime drowsiness, irritability, impaired memory, or hard to concentrate.2 The term post-stroke insomnia is defined as insomnia that arises after stroke.3

Insomnia can be diagnosed through the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire (KSQ). KSQ includes psychometric parameters and three validated parts, according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders criteria. Besides, the diagnosis of insomnia can be established through the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) questionnaire with a sensitivity of 86.1% and a specificity of 87.7% for detecting insomnia.7,8

Insomnia is a hyperarousal disorder, increased somatic, cognitive, and cortical activation. Individuals with insomnia tend to show hyperarousal experiences in the central (cortical) and peripheral (autonomic) nervous system.9

Circadian sleep tendencies are regulated by intrinsic circadian oscillations in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus. Visible light, melatonin, and social factors can influence the circadian process, such as REM sleep, body temperature, and endogenous melatonin.9,10

Insomnia treatments include medical therapy, such as benzodiazepine (zolpidem) agonists and behavioral interventions. The main nonpharmacological intervention is a behavioral intervention. The latter is stimulus control therapy, sleep restriction therapy, and sleep hygiene education. The elements of this treatment focus on (1) improving the relationship between bed and sleep; (2) rebuilding a consistent sleep–wake schedule; (3) limiting time in bed to increase sleep drive and resulting in sleep efficiency; (4) maintaining good sleep practices.9,10

Behavioral intervention in insomnia includes cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or brief behavioral treatment insomnia (BBTI), which is an adaptation of standard CBT for insomnia. CBT-I is the gold standard for insomnia.11 A meta-analysis study found that CBT-I could improve sleep quality with significant improvements to ISI and was an effective and long-lasting treatment for comorbid insomnia.12 CBT-I is a first-line therapy.12 There is more limited evidence for shorter versions of treatment, such as one-session meetings and self-help material.13,14 BBTI is a natural, effective intervention for patients with chronic insomnia.13 BBTI is associated with significant improvements in sleep measurement and can be a promising therapy for insomnia.15 BBTI produces complete remission from insomnia.16

The high incidence of post-stroke insomnia and the presence of effective non-pharmacological therapies for insomnia. Therefore, researchers wanted to examine the effect of behavioral intervention therapy on improving the severity of post-stroke insomnia with some modifications in the inpatient and outpatient settings of Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo Hospital and its network in Makassar.

MethodResearch locationThis study was conducted in an outpatient and inpatient at Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo Teaching Hospital for two months. It used the ISI score to assess the severity of insomnia. The subject was divided into the control and intervention groups which each group consists of 12 people. A subject in the intervention group was given behavioral intervention for 30min.

Types and sources of dataThe data to be measured from the samples were data related to the demographic data, medical diagnosis, onset, brain lesion, and ISI score covering the severity degree of insomnia. The data were obtained by looking at the results of a medical record, head of CT scan, and ISI score.

Data collection techniquesISI score was measured twice in each group. The first measurement was taken when the sample meets the inclusion criteria. The intervention group was given a 30min behavioral intervention, which included sleep restriction, stimulus control therapy, and sleeps hygiene. Then, the ISI score was measured after two weeks in both groups. ISI scores were categorized as severe insomnia, moderate insomnia, mild insomnia, and healthy.

ResultThis study aims to determine the effect of behavioral intervention on the severity of insomnia. This research was conducted at the Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo Teaching Hospital and its network consisting of a control and intervention group. Each group consists of 12 respondents. Respondents consisted of 15 men and nine women. The control group consisted of 6 homemakers, three retirees, a civil servant, a police officer, and an entrepreneur, while the intervention group consisted of 5 housewives, a pensioner, a private company worker, and an entrepreneur.

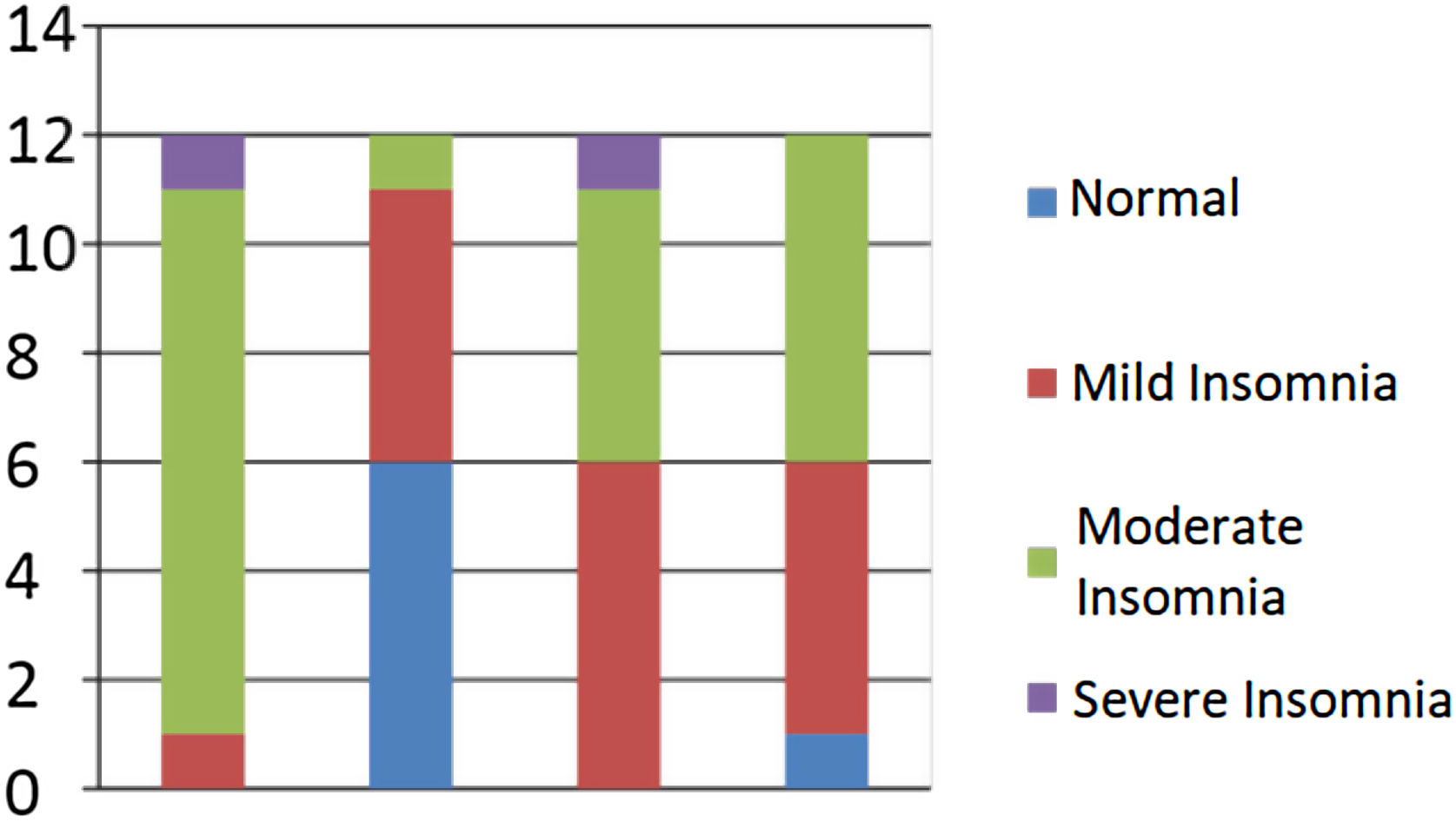

When reviewed from the location of the lesion, in the control group, there are six respondents with lesions on the right side, four respondents had lesions on the left side, one respondent had bilateral lesions, and one respondent had lesions, not including both. In the intervention group, nine respondents had lesions on the right side, two respondents had lesions on the left side, and one respondent had bilateral lesions (Figs. 1 and 2).

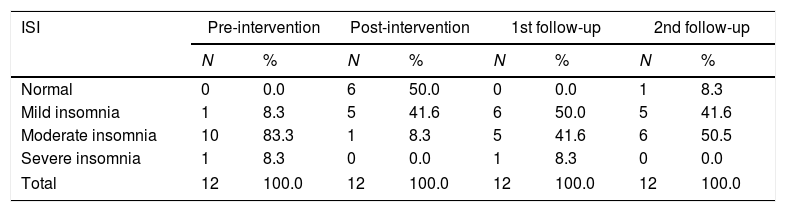

Table 1 shows a significant improvement in the ISI score on the intervention group (p<0.001) but did not show a significant change in the control group.

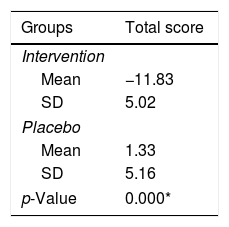

The results of this study showed a significant improvement in the ISI score on the intervention group compared to the sample group (p<0.001), which can be seen in Table 2.

Comparison of the severity of post-stroke insomnia in the intervention group compared to the control group.

| Groups | Total score |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

| Mean | −11.83 |

| SD | 5.02 |

| Placebo | |

| Mean | 1.33 |

| SD | 5.16 |

| p-Value | 0.000* |

Ages over 65 years were not included in the inclusion criteria because there was a linear decrease in the percentage of NREM N3 and REM sleep.17

There was an improvement in the ISI score on several samples within controls showing the evolution of post-stroke sleep due to neural network reorganization. Changes in post-stroke sleep and stroke evolution coincide (Table 3).18

Distribution of samples based on the severity of post-stroke insomnia.

| ISI | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | 1st follow-up | 2nd follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Normal | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| Mild insomnia | 1 | 8.3 | 5 | 41.6 | 6 | 50.0 | 5 | 41.6 |

| Moderate insomnia | 10 | 83.3 | 1 | 8.3 | 5 | 41.6 | 6 | 50.5 |

| Severe insomnia | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 12 | 100.0 | 12 | 100.0 | 12 | 100.0 | 12 | 100.0 |

ISI score in the intervention group compared to the control group showed a significant value (p<0.001). This study indicates that the causes of insomnia in post-stroke patients are precipitating factors and perpetuating factors based on Spielman's theory. The precipitating factor in this study is a stroke, whereas the perpetuating factor is a factor that arises as a result of acute insomnia. Preserving factors are environmental and behavioral cues that aggravate insomnia with the ongoing relationship between insomnia – situations and behavior related to sleep.19

Behavioral intervention through the approach of stimulus control therapy, sleep restriction therapy and sleep hygiene education can control perpetuating factors to reduce the severity of insomnia.14,16,20,21

ConclusionsThe results of this study show that behavioral intervention significantly improves the severity of post-stroke Insomnia. Therefore, behavioral intervention could be one of the non-pharmacological therapy for post-stroke insomnia.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.