Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019)

Más datosTo know the effect of white noise on the sleep quality at high senior students in Putri Rajawali Makassar.

AimThis study aimed to evaluate the effect of white noise on the sleep quality of high school students at Unit B of Rajawali Girls Dormitory Makassar.

MethodsThis was an experimental study involving twelve subjects, ages 16–18, with a total sampling method. The JBL T5 speaker was placed in the subject's room to generate white noise for 30 days. The white noise was listened continuously from 10 pm to 5 am, and sleep quality was measured subjectively with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) before and after the intervention. Then the data were analyzed by paired t-test.

ResultsThe mean of PSQI score before the intervention was 8.50±2.5 and significantly decrease into 6.50±3.00 after the intervention (p-value 0.019).

ConclusionWhite noise decreased the score of PSQI, which interpreted as better sleep quality.

Sleep is essential for children and adolescents that can affect learning, memory, and performance at school. Sleep can be defined as a state of active, recurrent, and reversible withdrawal of the environment. Healthy sleep requires adequate duration, appropriate time, quality, regularity, and the absence of specific disorders and diseases.1 Sleep is related to brain processes at night, which are believed to affect cognitive, physical, and emotional performance throughout the day. The relationship between sleep, cognitive function, and performance in school is essential for neurocognitive function.2,3 It based on the opinion that the lack of sleep disturbance can affect brain activity at night. Complex activities require abstract thinking, creativity, integration, and planning, which are mainly influenced by problems related to sleep. These activities present sublime cortical functions, all of which are characterized by the influence of the prefrontal cortex, which is known to be sensitive to sleep. Based on some evidence, poor or inadequate sleep quality during early adolescence can affect the executive function of the prefrontal cortex and consequently reduce learning ability and performance in school.4

Sleep quality and duration can be seen as two different sleep domains. Although the two things overlap, there are qualitative differences between them. Sleep quality refers to subjectively how sleep experiences are, among others, feelings after awakening and satisfaction with sleep itself. Besides, sleep duration is a more objective domain of sleep, that is, the individual's time of actual sleep. Although these two domains are associated with sleepiness, emotional status, behavioral and cognitive functions, this is more strongly related to sleep quality than sleep duration.4

Several studies have shown that poor sleep quality, increased sleep fragmentation, late sleep, and early waking can affect learning abilities, performance at school, and student behavior.4 Parental supervision and complaints of sleep disorders in children vary. Parents usually pay more attention to sleep problems in infants and toddlers than school-age children and teenagers. For example, based on a poll conducted by the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) found that only 7% of parents knew sleep disturbance in their teenage children, while 16% of teenagers were aware of it. One in 3 of these adolescents did not tell anyone about their sleep problems.5 Problems with starting sleep and maintaining sleep are common in children and adolescents and can indicate poor sleep quality.4 Based on a meta-analysis of children conducted from 20 countries concluded that children ages 13–18 have an increased ratio of accidents in children whose sleep duration is less than 7 or 8h, and better health in children who sleep for 9h or more. A meta-analysis found that sleep duration decreased continuously from 9 to 10h at 13 years of age and less than 8–9h at 18 years. Inadequate sleep can be caused by the interaction of intrinsic factors (e.g., puberty, circadian rhythm or homeostatic and extrinsic changes (e.g., school time, social pressure, and piles of academic work) that can cause late sleep while waking time does not change.1

The most critical consequence of sleep disorders is increased daytime sleepiness, with a prevalence of 20–50% in children and adolescents. Daytime sleepiness is caused by poor sleep quality, lack of sleep duration or a combination of these two things.4

Staying in a dorm can affect the quality and quantity of students’ sleep, which can affect academic performance. According to research conducted by Bahrami M. et al., the sleep quality of students living in dormitories is not a favorable situation and is a significant health problem.6 Some studies indicate that students who live in dormitories have poor sleep quality, as in studies in China and North America. Whereas in Palestine and South America, sleep disturbance is lower in students who live in dormitories.7

Auditory stimulation is one of the convenient and effective alternatives that some people do when doing activities. Auditory stimulation defined as an event or something that provokes a specific functional reaction of a tissue or organ, for example, sounds that affect our auditory sensations. When sound causes changes in air pressure or other elastic media, it can cause stimulated auditory stimuli. Generally, the loudness of sound is measured in decibels and enters the ear as a wave. The human ear can detect sounds that have a frequency of 20–20,000Hz.8

White noise consists of a combination of constant sound frequency variations and comes from the environment, monotonous sound that can disguise all the sounds from the surrounding environment that are quite disturbing.9 The mechanism of white noise can improve sleep quality is still unclear.10 Some research abroad shows that listening to white noise can improve sleep quality continuously by increasing the acoustic threshold to the maximum so that the surrounding noise is less able to stimulate the brain during sleep. Some research also shows that white noise affects the electrical activity of the brain and improves sleep quality by reducing the latency of sleep onset and triggering deeper sleep so that it can improve one's sleep architecture.10–12

Based on the description above, we are interested in researching the effect of white noise on the sleep quality of individuals who are the subject of our study.

MethodsThe design of this study is a pre-experimental study. The study population consisted of 12 residents of Unit B of Putri Rajawali Makassar dormitory who met the inclusion criteria as follows: (1) permanent residents of Unit B of Makassar Rajawali Dormitory, (2) ages 13–18 years, (3) had no hearing loss, (4) had no condition certain medical conditions that cause sleep disorders. Samples obtained by total sampling method where the number of samples is equal to the population.

Data collection began when residents of Unit B of Putri Rajawali Makassar Dormitory filled out a consent form to participate in this study. Participants were asked to fill in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire as an initial measure of sleep quality before the intervention. Then the researchers installed the JBL T5 speaker in the participant's bedroom. The white noise used in this study is the sound of 60min of rain played every night for 30 days when participants enter the room at 22:00 to wake up at 05.00. On the 30th day, participants were asked to re-write the PSQI questionnaire to measure sleep quality after the intervention. The cut-off value of the PSQI questionnaire is >5, which means poor sleep quality. The distribution of the study sample was declared normal after passing the Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical data was processed by a paired t-test and processed using SPSS version 25.

ResultThis research was conducted in Unit B of Putri Rajawali Makassar Dormitory in April–May 2019. In this study, the same number of samples was obtained with a population of 12 people.

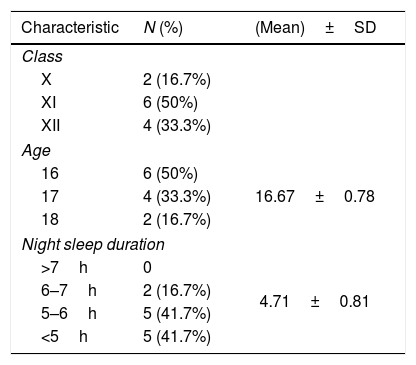

Based on Table 1 shows that most participants came from class XI with a percentage of 50% (6 people), while the rest were class X 16.7% (2 people) and class XII 33.3% (4 people). Participants aged 16–18 years with a percentage of 50% (6 people) aged 16 years, 33.3% (4 people) aged 17 years, and 16.7% (2 people) aged 18 years. The average sleep duration of participants lasted for 4.71±0.81h each night, where as many as 41.7% (5 people) slept for <5h, 41.7% (5 people) slept for 5–6h, and 16.7% (2 people) slept during 6–7h.

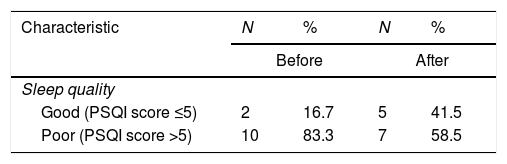

Based on Table 2, before giving white noise stimulation showed that 83.3% (10 people) participants had poor sleep quality, while only 16.7% (2 people) had good sleep quality. After administering white noise stimulation, participants who had good sleep quality increased to 41.5% (5 people), while 58.5% (7 people) had poor sleep quality. Although still in the poor category, there was a decrease in PSQI scores in most participants after the intervention with white noise.

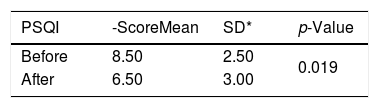

Based on Table 3, the mean PSQI score before the intervention was 8.50±2.5, while after the intervention, it became 6.50±3.0. The data is then processed using a paired t-test so that it gives results p=0.019 (p<0.05). Based on these statistical data, it is known that there is an effect of white noise on improving sleep quality.

Paired t-test results of sleep quality of samples against white noise stimulation.

| PSQI | -ScoreMean | SD* | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 8.50 | 2.50 | 0.019 |

| After | 6.50 | 3.00 |

The subjects of our study were all high school students aged 16–18 who had an average sleep duration of 4.71±0.81. According to the recommendations of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the ± duration of adequate sleep in adolescents aged 13–18 years is 8–10h.1 When comparing the two data, and our study subjects have a sleep duration that is still lacking when compared to adolescents in general. It is due to the daily schedule of activities set by the local dormitory.

Before the white noise intervention, almost all participants in this study had poor sleep quality (PSQI score>5), where the mean PSQI score was 8.50±2.50. Sleep quality measurements were carried out using a PSQI questionnaire consisting of 7 components, namely objectively quality night sleep, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, disruption when sleeping at night, use of sleeping pills, and dysfunction in daytime activities. Most participants said that their sleep quality was quite good, sleep latency was more than 15min, lack of sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance at night, no use of sleeping pills, and dysfunction in daytime activities more than three days a week.

Interventions given to improve participants’ sleep quality are white noise stimulation that is played every night for 60min as a lullaby, where white noise can affect the electrical activity of the brain and improve sleep quality by reducing the latency of sleep onset and triggering deeper sleep to improve sleep architecture of a person.10–12

After completing the intervention for the participants for 30 days, based on the results of the post-test, the mean PSQI score decreased to 6.50±3.00. Some participants said there was an increase in sleep quality, improved sleep latency, improved sleep efficiency, reduced frequency of sleep disturbance at night, no use of sleeping pills, and improved dysfunction in daytime activities. Two participants experienced a decrease in sleep quality, where an increase in PSQI scores. It can occur because there are still many external factors that can affect the quality of participants’ sleep beyond the control of the researcher.

Based on our statistical data, namely the paired t-test to assess the pre-test and post-test of our study subjects, the results were found to be p=0.019, which means that there is an influence of white noise stimulation interventions on improving the sleep quality of our study subjects. It is following several studies that have been done previously abroad, where there was a significant improvement in the quality of sleep in the research subjects.

ConclusionPoor sleep quality is common in individuals who live in dorms. Based on data obtained from this study, the use of white noise can be one method that can improve the sleep quality of someone who lives in a dormitory.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.