Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019)

Más datosThe general objective of this study was to determine the relationship between sleep quality and pain intensity in chronic low back pain patients.

MethodCross-sectional analytic study with consecutive sampling. Chronic patients who met the inclusion criteria at clinic neurology Wahidin Sudirohusodo Makassar. Independent variable: sleep quality, measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)score. Dependent variable: pain intensity, measured by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)score. Data analysis using a Chi-Square test.

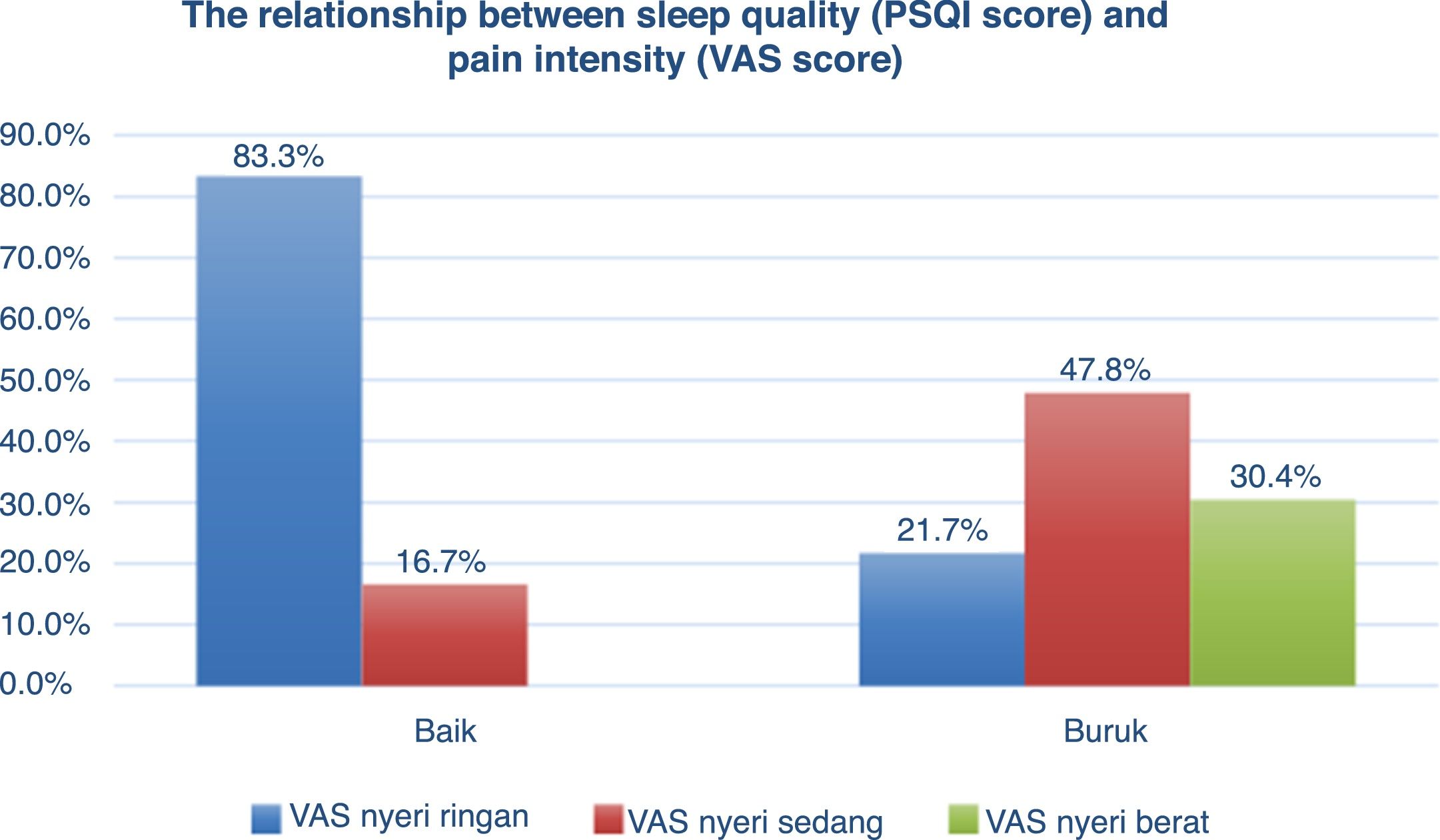

ResultA total of 29 samples met our inclusion criteria and divided into two groups, 23 samples of poor sleep quality, and six samples of good sleep quality. Within the poor sleep quality group, five patients (21.7%) had mild pain intensity, 11 patients (47.8%) had moderate pain intensity, and seven patients (30.4%) had severe pain intensity. In good sleep quality, five patients (83.3%) had mild pain intensity, one patient (16.7%) had moderate pain intensity, and no samples with severe pain intensity. A significant relationship found between sleep quality and pain intensity (p=0.017).

ConclusionThere is a relationship between sleep quality and pain intensity. Poor sleep quality is associated with increased pain intensity in patients with chronic low back pain.

Sleep is defined by the Sleep Disorders Management Guide (2017) by the Sleep Disorders Study Group of the Indonesian Neurologist Specialist Association (PERDOSSI). Sleep is defined by the Sleep Disorders Management Guide (2017), the Sleep Disorders Study Group of the Indonesian Neurologist Specialist Association (PERDOSSI) is a reversible decrease in consciousness that is a physiological and recurrent form, usually, a decline in cognitive function globally, so the brain does not respond to surrounding stimuli. The function of sleep can be seen by the fact that people spend about a third of their lives sleeping. Sleep quality has several components that involve a variety of domains, including assessments of sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep dysfunction, and the use of sleeping pills, if one or more of the disrupted domains will result in decreased sleep quality. Poor sleep quality has been associated with increasing age, low socioeconomic status, poor general health, poor lifestyle behavior. Changes in terms of quality, quantity, and sleep patterns cause sleep disturbance. Sleep disorders that occur continuously and repeatedly are important predisposing factors for the development of chronic diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, depression, cancer, stroke, chronic back pain, and decreased quality of life. Sleep disturbance is proven to increase the stress response so that it can delay the healing process, causing sequelae that are detrimental to the cardiovascular system, metabolism, and endocrine. Moreover, it can cause hyperalgesia and contribute to the dysregulation of emotional reactivity.1–6

In the United States, there are 50–70 million adults who have sleep disorders with the proportion of insomnia of 6–10% and sleep apnea of 10–25%. The Center on Sleep Disorders Research estimates that 38,000 deaths occur per year for cardiovascular cases due to sleep disorders. Another study conducted in the Netherlands with a total of 20,000 patients aged 12 years or older showed an alarming prevalence, with 21.2% of men and 33.2% of women having some type of sleep disorder. 3,7

Based on the Alsaadi et al. study, data for 1936 patients were taken from 13 other author studies between 2001 and 2009, found the prevalence of sleep disorders in patients with low back pain by 58.9%. Another study conducted by Franca et al., in 51 patients with chronic low back pain found 82.35% of patients with sleep disorders. According to research conducted by Donoghue et al., Mentioned that patients with chronic low back pain (chronic NPB) have significantly poor sleep quality, both subjectively and objectively. This study also showed a statistically significant relationship between low back pain with disability levels and subjective sleep quality. 8

Sleep disturbance has a considerable economic impact. The economic impact of the annual cost of treating moderate-severe sleep disorders in the United States is 165 billion US dollars, far higher than other non-communicable diseases such as heart failure, stroke, hypertension, asthma (20–80 billion US dollars). 2

Chronic pain and sleep disorders have a reciprocal relationship and are often found together. Sleep deprivation of eight hours each night is considered to be of reduced sleep duration and can cause long-term disruption in sleep patterns. Reduced sleep duration and poor sleep quality can reduce pain threshold in subjects experiencing pain and mental capacity to cope with pain, and vice versa i.e., chronic pain can cause a decrease in sleep quality. Sleep disturbance is a common problem that is often found as much as 50–70% in patients with chronic non-malignant pain. Sleep disorders in patients with chronic pain such as chronic LBP cases, include a variety of factors and are characterized by reduced sleep efficiency, sleep duration, increased sleep latency, daytime sleepiness. Difficulty in starting and maintaining sleep is a symptom that is often found in the general population. Difficulty in going to sleep, maintaining sleep, waking up earlier has been found in chronic pain patients. Chronic LBP is one of the most common symptoms of chronic pain. Decreased slow-wave sleep appears to be responsible for increased sensitivity to pain. 9,10

Based on several studies that show a relatively high prevalence and sizable economic impact for cases of chronic low back pain with sleep disorders, the researchers aim to study there is a relationship between sleep quality with pain intensity in chronic low back pain patients. Subjective sleep quality was assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). PSQI is an effective instrument for measuring sleep quality and patterns in adults, which can distinguish between “poor” and “good” sleep quality through 7 components. Pain intensity assessed by visual analog scale (VAS) score, VAS is an instrument for valid and reliable pain assessment. 11,12

MethodThis study is a type of observational analytic study using cross-sectional studies. The study was conducted at the Neurology Polyclinic of the Wahidin Sudirohusodo Education General Hospital and the Network Hospital, in April–May 2019. The study population was all patients with chronic low back pain who sought treatment at the Poly Neurology of Wahidin Sudirohusodo Education Hospital and the Network Hospital, in the month of April–May2019. The sample of this study was chronic low back pain sufferers who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The sample obtained by a consecutive sampling method. The inclusion criteria used (1) Patients aged 18–65 years, both male and female with significant complaints of low back pain that have been experienced for more than 12 weeks (3 months) and visited the Neurology Wahidin Sudirohusodo General Hospital and Network Hospital in April–May 2019. (2) Samples are willing to be included in this study by giving signatures for informed consent and filling out research questionnaires. Subjects were excluded from the study if: (1) Patients who have other musculoskeletal disorders, (2) Patients with low back pain due to disorders of the visceral organs such as infection and kidney stones, (3) Patients who get serious illnesses, such as malignancy or other complications, (4) Patients who get other intracranial disorders.

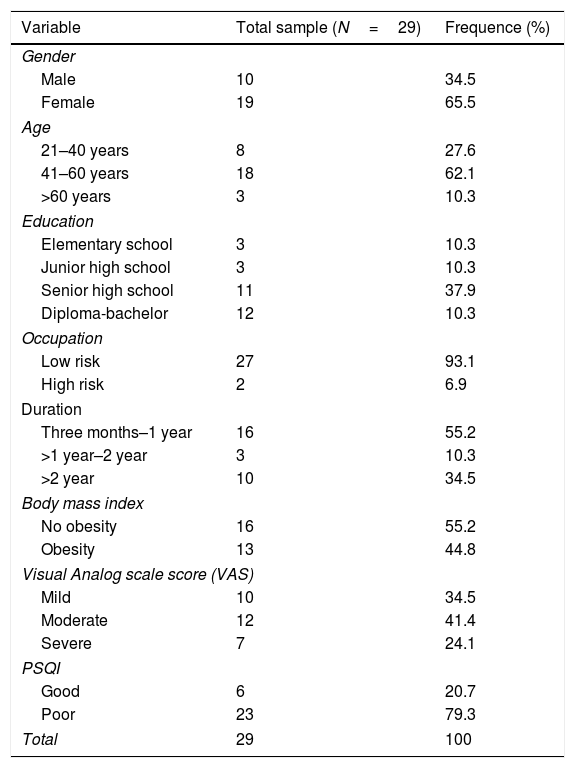

ResultCharacteristics of subjects with chronic low back painThis study was conducted at Wahidin Sudirohusodo General Hospital and Network Hospital in April–May 2019. Table 1 shows, a total sample of 29 people was obtained with a higher number of women, 19 of them (65.5%), and as many as men ten people (34.5%). Based on education and employment, patients with chronic low back pain who received elementary school education were three people (10.3%), junior high school as many as three people (10.3%), high school as many as 11 people (37.9%), and Diploma-there were 12 scholars (41.3%). While in terms of work divided into high-risk work and low risk of chronic low back pain. Heavy and rough work is considered as a job with a high risk of 2 people (6.9%), and low-risk jobs of 27 people (93.1%). Based on the data, diplomas-scholars have the most chronic low back pain, while many low-risk jobs experience chronic low back pain (Fig. 1).

Characteristic data of chronic low back pain subjects.

| Variable | Total sample (N=29) | Frequence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 10 | 34.5 |

| Female | 19 | 65.5 |

| Age | ||

| 21–40 years | 8 | 27.6 |

| 41–60 years | 18 | 62.1 |

| >60 years | 3 | 10.3 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary school | 3 | 10.3 |

| Junior high school | 3 | 10.3 |

| Senior high school | 11 | 37.9 |

| Diploma-bachelor | 12 | 10.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Low risk | 27 | 93.1 |

| High risk | 2 | 6.9 |

| Duration | ||

| Three months–1 year | 16 | 55.2 |

| >1 year–2 year | 3 | 10.3 |

| >2 year | 10 | 34.5 |

| Body mass index | ||

| No obesity | 16 | 55.2 |

| Obesity | 13 | 44.8 |

| Visual Analog scale score (VAS) | ||

| Mild | 10 | 34.5 |

| Moderate | 12 | 41.4 |

| Severe | 7 | 24.1 |

| PSQI | ||

| Good | 6 | 20.7 |

| Poor | 23 | 79.3 |

| Total | 29 | 100 |

Baseline data of the subjects showed the distribution of the age group, the group of patients aged 21–40 years as many as eight people (27.6%), the group of patients aged 41–60 years as many as 18 people (62.1%), the group of patients with age >60 years amounted to 3 people (10.3%). While the duration of pain three months – 1 year has the most subjects experiencing chronic low back pain as many as 16 people (55.2%), duration of 1 year-2 year by three people (10.3%), and duration > 2 years of 10 people (34.5%). Obese patients with chronic low back pain were 13 people (44.8%), and not obese as many as 16 people (55.2%).

Based on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score, the number of chronic low back pain patients who had mild pain intensity was ten people (34.5%), the most intensity was moderate pain by 12 people (41.4%), and severe pain as much as seven people (24.1%). The PSQI questionnaire assessed the sleep quality of chronic low back pain patients. Chronic low back pain subjects with good sleep quality were six people (20.7%), while poor sleep quality were 23 people (79.3%).

The relationship between sleep quality and pain intensityIn Table 2 shows the number of subject groups of good and poor sleep quality on pain intensity. In subjects with good sleep quality, they have mild pain intensity as many as five people (83.3%), moderate pain one person (16.7%), and there were no subjects with severe pain intensity. Whereas the subjects with poor sleep quality have mild pain intensity as many as five people (21.7%), moderate pain as many as 11 people (47.8%), and severe pain as many as seven people (30.4%), with a P-value=0.017.

DiscussionChronic pain that is most often complained of by people is chronic low back pain. The effects of chronic LBP include considerable clinical, social, and economic aspects throughout the world. Chronic LBP has multifactorial causes such as work or physical activity, body mass index associated with obesity, socioeconomic level, and education.

In this study, there was a total sample of 29 people with chronic low back pain, and women had a higher population than men at 65.5% and 34.5%. Chronic LBP consistently has a higher proportion of women than men. One reason for this is that women are shown to have lower pain perception thresholds, and menstrual cycle fluctuations affect pain sensitivity, but if chronic LBP is related to work, the proportion of men is higher. The number of chronic LBP subjects with high-risk work in this study was only two people, and both were male.

Based on the age of patients who experience chronic low back pain, they obtained the age with the largest population between 41 and 60 years that is as many as 18 people, with an average age of 44 years. According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the first attack of low back pain occurs at the age of 30–50 years, and lower back pain becomes more common with age because increasing age is associated with decreased bone density, reduced elasticity and muscle tone, flexibility intervertebral discs are reduced. Chronic LBP subjects were 13 people obese, and 16 people were not obese. Chronic LBP is strongly influenced by obesity because obesity causes an emphasis on the intervertebral discs, the greater cartilage.

In this study, more subjects were not obese, chronic LBP occurred due to multifactorial influence, so it is possible that the cause of chronic LBP is by other factors.

Based on pain intensity assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS) score, it was found that the most subjects experienced moderate pain intensity as many as 12 people. In contrast, the intensity of mild pain was ten people, and severe pain was seven people, then subjects were also subjected to subjective sleep quality using the PSQI questionnaire. Poor sleep quality with more prevalence than good sleep quality, as many as 23 people and six people. In this study, the prevalence of poor sleep quality was higher than good sleep quality. This number is following several studies that showed a higher prevalence of sleep disorders in patients with chronic low back pain.

The relationship between sleep quality and pain intensity was tested using chi-square and statistically significant, which is P=0.017. In the group that had poor sleep quality tended to have moderate and severe pain intensity with a moderate pain population of 47.8%, severe pain 30.4%, and mild pain 21.7%. While the group with good sleep quality tends to have mild and moderate pain intensity with a population of mild pain 83.3% and moderate pain 16.7%. The effect of sleep quality on pain intensity is strengthened by the absence of subjects with good sleep quality who have severe pain intensity. These results are consistent with the study of Marin et al. (2006), which states that sleep disturbance is a common finding in cases of chronic low back pain, an increase in pain intensity in patients with chronic low back pain influenced by poor sleep quality.

There is increasing evidence that poor sleep quality affects increasing mortality in certain diseases and susceptibility to infections. Acute and chronic reduction in the duration and quality of sleep has been shown to induce excessive expenditure from proinflammatory cytokines. IL-6 is one of the most critical cytokines that mediate the rapid interaction between the immune system and the central nervous system function. Poor sleep quality causes a significant increase and peak of IL-6 levels the next day. This level can be reduced if the patient sleeps during the day. Exogenous administration of IL-6 has been shown to have a somnogenic effect in studies conducted on experimental animals, besides activating hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA), which causes nonphysiological hypercortisolemia during the first hour during sleep which explains the decline in sleep quality. Whereas IL-6 increases pain intensity in neuropathic pain. In this study, subjects with poor sleep quality had moderate to severe pain intensity, while subjects with good sleep quality had mild to moderate pain intensity. Statistically has a significant relationship between sleep quality and pain intensity in chronic LBP cases, with a p-value<0.05 (p=0.017).

This study is a preliminary study to see the relationship between sleep quality and pain intensity in chronic LBP cases. The limited number of samples and subjective sleep quality measurement tools in the form of PSQI questionnaires are the weaknesses of this study. Subsequent studies can use direct IL-6 serum levels, which influence pain intensity and sleep quality.

ConclusionThere is a relationship between sleep quality and pain intensity in chronic low back pain patients. Poor sleep quality is associated with an increase in pain intensity in chronic low back pain patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.