Recruitment and selection of gamete donors has become during the years a challenge for doctors and psychologists due to the importance of selecting the best candidate. But, is there a donor female and male profile? The objective of this study is to investigate the socio-demographic and motivational characteristics of female and male gamete donor candidates at a fertility clinic in order to find a prediction profile for donors and to detect how their characteristics change over time.

Material and methodsA transversal predictive design and a comparative design were used, and 1338 women and 137 men donor candidates at the Alicante IVI Center in Spain in the 2007–2013 period participated in the study. Data were obtained from semi-structured interviews.

ResultsBeing younger, in active employment and having a partner increases the likelihood of women becoming donors. Similarly, if women candidates have completed secondary or university education, do not smoke and have a partner, it is more likely they will be determined as suitable candidates in the psychological assessment. However, there does not appear to be a defined profile for men. The profile for a financially compensated donor candidate has shown significant changes over time; changing from being in active employment to being unemployed, but the motivations have remained the same.

DiscussionThese findings can be a valuable tool which can lead to improvements in the selection process for financially compensated gamete donor candidates.

El reclutamiento y selección de los donantes de gametos ha constituido durante años un reto para médicos y psicólogos debido a la importancia de seleccionar al mejor candidato. Pero, ¿existe un perfil de donante femenino y masculino? El objetivo de este estudio es investigar las características sociodemográficas y motivacionales de candidatos a donantes femeninos y masculinos en una clínica de fertilidad, con el propósito de encontrar un perfil predictivo para los donantes y detectar cómo sus características evolucionan con el tiempo.

Material y métodosSe utilizó un diseño transversal predictivo y un diseño comparativo, y 1.338 mujeres y 137 hombres candidatos a donantes en el centro IVI Alicante en España en el período 2007-2013 participaron en el estudio. Los datos se obtuvieron a través de entrevistas semiestructuradas.

ResultadosSer más joven, en activo laboralmente y tener pareja incrementa la probabilidad de llegar a ser donante en mujeres. De forma similar, si las candidatas han completado la educación primaria o universitaria, no fuman y tienen pareja, es más probable que sean calificadas como candidatas adecuadas en la evaluación psicológica. Sin embargo, no parece existir un perfil definido para los varones. El perfil para el candidato a donante compensado económicamente ha mostrado cambios en el tiempo significativos, pasando de ser laboralmente activo a ser desempleado, pero sus motivaciones se han mantenido.

DiscusiónEstos hallazgos constituyen una valiosa herramienta que puede llevar a mejoras en el proceso de selección de los candidatos a donantes de gametos compensados económicamente.

According to data from the last annual report provided by the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), the overall number of assisted reproduction techniques (ART) cycles has continued to increase yearly (Kupka et al., 2016). In Spain, the data suggest the same trend (Sociedad Española de Fertilidad, 2014). This is partly a result of the high success rate of reproductive treatment when donor oocytes are used, and the tremendous growth in the number of clinics that provide oocyte and sperm donation for infertility treatment (Hershberger, 2004). There has also been a notable increase in the demand for oocyte donation cycles due to the social changes experienced in recent decades, which has led to women to delay their first pregnancy, with the result that reproduction problems arise from a decrease in the number and quality of oocytes. However, it has not been an easy path for Medicine, since it has taken decades to achieve gestation with donated female gametes in comparison to male gamete donation. This has been due to the relative difficulty in obtaining female gametes, problems arising from the need to synchronize cycles between oocyte donors and recipients, as well as the delay in having a reliable and efficient technique for freezing and thawing oocytes (vitrification) with clinical rates comparable to those for fresh oocytes. Furthermore, it should be considered that obtaining gametes is difficult: for males it is relatively simple, whereas for females it involves an invasive procedure, which entails a guided transvaginal puncture under anesthetic, preceded by a period of parenteral administration of gonadotropins.

In recent years, however, recruitment of semen donors has become more stringent, since screening for sexually transmitted diseases and higher semen quality standards affect the number of candidate semen donors that are released (Paul et al., 2006). However, gamete donation in Spain is anonymous (Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2006), leading to less reticence by donor candidates, which is not the case in other countries where they have had to develop strategies like “egg sharing” for obtaining oocytes, which has been regulated since 1998 (Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, 1998). Another factor that has contributed favorably to candidates deciding to donate eggs in Spain is that in 1998, the “Comisión Nacional de Reproducción Humana Asistida” (CNRHA) (National Commission for Human Assisted Reproduction) stated that financial compensation would be permitted for the inconvenience arising from travel and the loss of time which could affect employment. This is not contemplated in those other countries, which decreases their number of donor candidates substantially. Spain also has a culture of being traditionally in favor of donation and has been a leader in these statistics for 20 years.

Therefore, the profile of gamete donors in Spain is pure donors, or non-patient donors (Purewal and van den Akker, 2009), and this prevents the obstacles that arise from shared donation such as suspicions that the reasons for donating are not altruistic, but respond to an interest in having access to the desired treatment. Another concern is for the psychological well-being of patients who have donated some of their eggs and whose treatment does not end successfully, and they think that they might have achieved their objective if they had not donated (Blyth and Golding, 2008).

The donation process is not exempt from both medical and psychological risks (Braverman, 2015; Giudice et al., 2007; Gurmankin, 2001; Murray and Golombok, 2000; Reh et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2011). Klock et al. (2003) state that the potential psychological risks of donating eggs can be classified into three categories: the psychological aspects of the donor screening process, the psychological aspects of the procedure itself, and a post-donation psychological adjustment to the donation. These risks are assessed by a psychological screening process that typically consists of a semi-structured interview where motivation is questioned. Also, psychologists search for factors that can exclude the applicant from being allowed to donate eggs or sperm.

Systematic reviews (Purewal and van den Akker, 2009; Van den Broeck et al., 2013) and other empirical studies (Cauvin, 2009; Daniels, 2000; Gürtin et al., 2012; Lindheim et al., 2001; Lucía and Núñez, 2015; Reh et al., 2010; Sauer et al., 1994; Schover et al., 1992; Svanberg et al., 2012; Thorn et al., 2008; Weil et al., 1994; Yee, 2009) have been conducted for many years to be able to describe the socio-demographic and motivational characteristics of potential oocyte and sperm donors. In general, the profile for women has been identified as someone who is well-educated, with mainly altruistic motivation, living with her partner and child (Pennings et al., 2014). Oocyte donors show a combination of altruistic and financial motivation (Purewal and van den Akker, 2009), which is the same for sperm donors (Schover et al., 1992; Van den Broeck et al., 2013; Vines, 1994).

These studies essentially use a descriptive methodology to try and reflect a profile of donors who usually apply for anonymous and financially compensated donation and a profile for altruistic and non-anonymous donors. They provide various descriptions of the characteristics of donor candidates, but do not identify which would be able to predict candidates as suitable for donation in the psychological assessment, nor do they identify which characteristics could predict which people would finally become donors and if they have varied over time, thereby improving the candidate selection process.

Objectives, research questions and hypothesesThis study fundamentally aims to find out the predictive socio-demographic and motivational characteristics for female and male donor candidate profiles that would lead to identifying individuals who would be suitable in the psychological assessment and whether they would finally become donors or not, as well as the study of whether these characteristics have changed over time, in order to provide resources to a better and more efficient selection process.

To do so the following questions are asked: (a) Is there a profile for a psychologically suitable female or male? (b) Is there a donor female and male profile? (c) Have these profiles changed over time, especially regarding their employment situation?

The hypotheses drawn from these questions, based on the revised literature, are:

- (1)

Candidates considered as psychologically suitable are characterized as being unemployed and not having a partner.

- (2)

The characteristics that define a predictive profile of female and male candidates who will finally become effective gamete donors are active employment and altruistic motivation.

- (3)

The candidate profile for female and male donors will change over time, evolving toward a higher level of education and being unemployed.

A transversal predictive design was used for the study of the predictive profile of donors and the profile of psychologically suitable donors, and a comparative design for the study of the evolution of socio-demographic data over time (Ato et al., 2013).

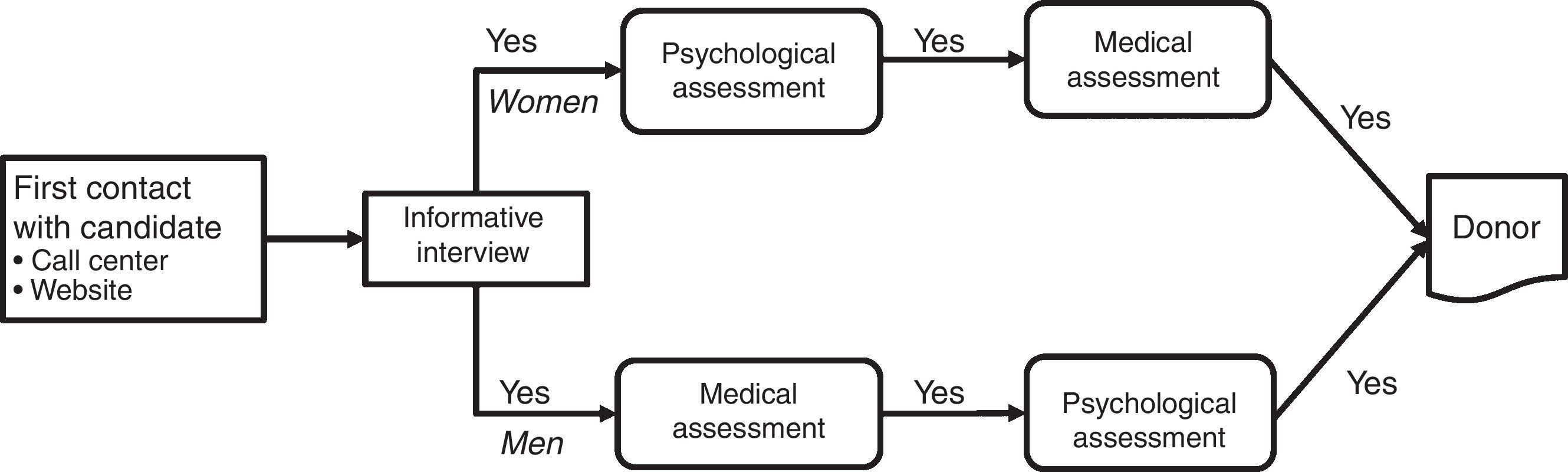

Candidates were selected according to the guidelines of Spanish legislation (Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2006). The procedure varies from women to men (see Fig. 1).

Gamete donor applicants must meet a series of requirements, which are: aged between 18 and 35, no family or personal history of genetically transmitted diseases, schizophrenia, depression, epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, alcoholism or breast cancer, no medical or surgical history of interest, and consent to participate in the process by signing the corresponding informed consent. After signing the consent, they are given a physical examination, and their weight and height are recorded; those candidates with a body mass index (BMI) of between 18 and 28 are selected. Women are also given a gynecological examination to establish anatomic normality of the pelvic organs and to evaluate the ovarian reserve; those donors with fewer than 10 antral follicles will be excluded. Men will have a spermiogram, whose parameters must be normal according to the WHO standards (World Health Organization, 2010) for them to be admitted to the program. Both women and men will also be psychologically assessed through a semi-structured interview.

If they meet the requirements, they will do complementary tests, such as a general analysis to check their general state of heath, blood type and RH factor, serological tests to exclude contact with AIDS, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, and karyotype.

To determine whether a candidate is psychologically suitable or unsuitable, the psychologist follows the guidelines outlined below, taking into account that the final decision is clinical. The donor candidate evaluated as suitable should have a clearly defined motive, regardless of its being altruistic or economical, and should also have a correct understanding of the medical procedure to be carried out, and the possible risks and side effects. Likewise, the candidate should be aware that their donation could result in the birth of human beings who will share their DNA as well as that of any children they may have now or in the future. The donor should intellectually and emotionally understand the difference between being a gamete donor and having a child. They will have to accept the uncertainty of not knowing whether or not their donation has resulted in the birth of a child or children. There should be no indications of any current or future interest in searching for or knowing data about the child or children that are born. There should be no fear or concerns, resulting from fantasies, about possible meetings between children born from donation and the donors themselves and their own children, nor any indications of future regret for having donated. Neither should they present any mental pathology, including eating disorders, or addictions of any type which could prevent them from having an organized life. Candidates who have had more than two voluntary terminations pregnancy will not be admitted.

Female applicants first call a Call Center or contact the center through the website to ask for information. Personal details are recorded (name, telephone number, date of birth, place of birth) and they are invited to a personal and free interview. A day or two before, they receive a reminder about the appointment. When the candidates go to the clinic, their personal details are completed, they are given the Informed Consent to be signed, and they are informed in detail about the donation process, the possible risks that it entails, the amount of financial compensation and the waiting times between the different selection processes (psychologist, doctors, compatible receptor, etc.). If they are interested, they are given an appointment for psychological assessment. If they are evaluated as psychologically suitable, they are given an appointment with gynecologists. While waiting for the gynecological results, they are asked about the date of their next menstruation, whether they take contraceptives and when they started taking them; information required to synchronize with the receptor. If the analysis results are anomalous they will be seen by gynecologists again, who will tell them the results. This also occurs if the psychological assessment shows they are not suitable for donation.

The procedure for men is similar to the one for women, but differs in that if they are interested they are given an appointment to give a semen sample and have a spermiogram, bringing a weekly semen sample for up to a maximum of 25 samples, and another blood test 6 months after quarantine. If the samples are of good quality, the applicant finally receives the psychological assessment. Therefore, in the case of men, those determined as psychologically suitable will already be medically suitable and technically become donors.

In both cases, donors receive a financial compensation. Financial compensation becomes effective for women only if donors reach the ovarian puncture stage. Compensation becomes effective for men in two parts – 65% on leaving the sample, and the remaining 35% after the corresponding analyses at six months, if the results are correct and the presence of infectious diseases is excluded.

Participants and settingsFemale and male gamete donor candidates from the Alicante IVI Center aged between 18–35 for women and 18–54 for men in the 2007–2013 period participated in the study. All men candidates who did not pass the medical tests were excluded and therefore did not do the psychological assessment.

Ethical approvalStudies at the IVI centers require that their ethical committee issues a favorable report prior to the study, as well as a preliminary legal report. The IVI Ethics Committee of Clinical Research approved the study, with the code 1410-ALC-072-JZ. Anonymity of the records was protected at all times by the center's strict protocol. All participants in the study signed the corresponding Informed Consent.

Instruments and variablesPsychological assessment was carried out by means of a standard semi-structured interview used in all the IVI centers, which is based on the diagnostic criteria DSM-IV-TR and validated by the Sociedad Española de Fertilidad (Spanish Fertility Society). This assessment method ensures for a more objective measure, and avoids a possible source of biases. The variables that this instrument measures are: sex, age, nationality, civil status, employment, educational level (no education, primary education degree, secondary education degree, or university degree) number of children (categorized too as having a child or not), death of a child, voluntary termination of pregnancy, motivation for donating (altruistic, financial, medical), tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption and drug consumption. Other aspects of interest were explored: personal background and family history of psychopathologies, adaptation disorders, mood disorders, addictions, eating disorders and behavior disorders. Apart from this, the aim was to accurately determine the motivation behind why a person is going to take the step of donating, the level of conviction and awareness of the consequences that doing this implies. Afterwards, data were obtained about those assessed from their results as psychologically and medically suitable, and finally whether they became donors, and in this case the number of donations they made.

Dependent and independent measuresFor the classification of the variables, in the predictive part the dependent variables were whether the result of the psychological assessment was suitable or unsuitable, and whether candidates finally donated or not. The rest of the variables became possible predictor variables. In the comparative study, time acted as the independent variable and the rest of the variables were dependent variables.

Statistical analysesThe descriptive and inferential statistics and the graphical treatment of the data were carried out using some packages of the R statistical system (R Core Team, 2016). The procedures were as follows.

First, in order to predict psychologically suitable and future donors, separate analyses were made for women and men using statistical modeling from the general linear model (GLM) with the R stats package (R Core Team, 2016), in a regression model with logistic binary response (logit) and in a saturated model with all the principal effects and their interactions. One of the advantages of using the GLM model is that it is possible to combine predictors measured on a quantitative scale with predictors measured on a category scale. The calculation method was iteratively reweighted least squares (IWLS). From this base model, and using a statistical modeling process, non-significant variables were eliminated until a more parsimonious model was reached. Goodness of fit of the model was evaluated using the information criteria by Akaike (AIC) and Pearson's chi-squared test. The analysis of outliers and influentials was done using Cook's Distance with the R ggfortify package (Horikoshi and Tang, 2015). Cases with missing data were eliminated.

In order to study the degree of association between categorical variables, two-dimensional contingency tables were analyzed, using the R vcd package (Meyer et al., 2015) and the R vcdExtra package (Friendly, 2016), using Pearson's chi-squared tests.

All the graphs were created using the ggplot2 package (Wickham, 2016).

ResultsSample descriptionThe final sample consisted of 1338 women and 137 men. 76.70% were Spanish, followed by 4.30% Colombian and 3.70% Argentinian. The remaining percentage (15.30%) consisted of people from different countries of the European Union, Ibero-America and Africa, in this order, and with percentages of up to 1.8%.

The average age for the women was 25.47, with a SD of 4.44 and a range of 18–35. The average number of children per women was 0.53 (65.55% had no children), with a range of 0–5, and a SD of 0.81. Having suffered the death of a child was 0.40%, with a range of 0–2, and voluntary termination of pregnancy was 25.80%, with a range of 0–4.

The average age for the men was 26.11, with a SD of 4.80 and a range of 18–35. The average number of children was 0.28, with a SD of 0.69 and a range of 0–5. Having suffered the death of a child was 0.80%, with a range of 0–1.

AssumptionsOne of the advantages to using logit models is that it is not necessary to meet the assumptions of traditional linear regression models (linearity, normality, homocedasticity and measurement level of variables). However, in this study the following conditions were met: the dependent variables are dichotomous, level one of these variables corresponds to the pursued condition, the terms of error are independent (that is to say, they are data from non-related samples), and the sample size is high.

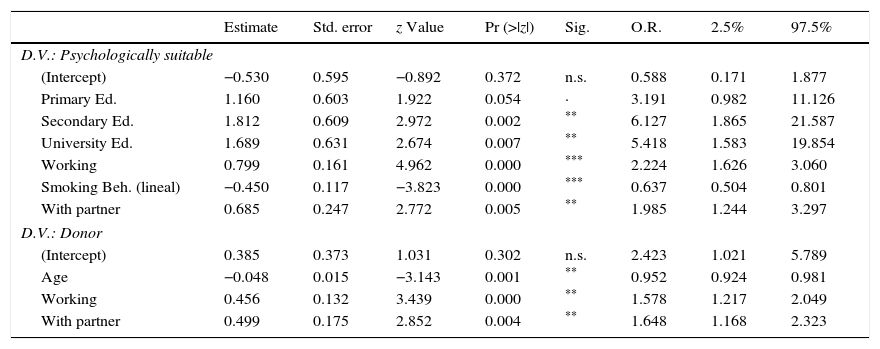

Prediction of the psychologically suitable profileOocyte donor candidatesThe model was estimated based on a saturated model including all the predictors, and based on Cook's distances, 3 outliers were eliminated. After eliminating the non-significant predictors, the resulting model contains 4 mutually independent predictors (see Table 1). The chi-squared test for nested models produced significant results between the base model and the final model (D(9)=28.676; p<.01). With respect to the model's goodness of fit, null deviance was 1425.9 on 1079 DF and residual deviance was 1404.0 on 1076 DF. The Wald Test for the whole effect of all the education categories (no education, primary education, secondary education and university education) was significant (D(3)=21; p<.001). The chi-squared test of differences between our model and the null model was significant (D(6)=84.404; p<.001). The model predicts that the probabilities of being suitable increase when a candidate has had a secondary or university education, works, does not smoke and has a partner.

Parameter estimation, significance and odds ratios of predictors of being a donor, and psychologically suitable. Age is expressed as a continuous variable, smoking behavior as ordinal (frequency), and the rest of the variables are dummy.

| Estimate | Std. error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | Sig. | O.R. | 2.5% | 97.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.V.: Psychologically suitable | ||||||||

| (Intercept) | −0.530 | 0.595 | −0.892 | 0.372 | n.s. | 0.588 | 0.171 | 1.877 |

| Primary Ed. | 1.160 | 0.603 | 1.922 | 0.054 | · | 3.191 | 0.982 | 11.126 |

| Secondary Ed. | 1.812 | 0.609 | 2.972 | 0.002 | ** | 6.127 | 1.865 | 21.587 |

| University Ed. | 1.689 | 0.631 | 2.674 | 0.007 | ** | 5.418 | 1.583 | 19.854 |

| Working | 0.799 | 0.161 | 4.962 | 0.000 | *** | 2.224 | 1.626 | 3.060 |

| Smoking Beh. (lineal) | −0.450 | 0.117 | −3.823 | 0.000 | *** | 0.637 | 0.504 | 0.801 |

| With partner | 0.685 | 0.247 | 2.772 | 0.005 | ** | 1.985 | 1.244 | 3.297 |

| D.V.: Donor | ||||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.385 | 0.373 | 1.031 | 0.302 | n.s. | 2.423 | 1.021 | 5.789 |

| Age | −0.048 | 0.015 | −3.143 | 0.001 | ** | 0.952 | 0.924 | 0.981 |

| Working | 0.456 | 0.132 | 3.439 | 0.000 | ** | 1.578 | 1.217 | 2.049 |

| With partner | 0.499 | 0.175 | 2.852 | 0.004 | ** | 1.648 | 1.168 | 2.323 |

D.V., dependent variable; O.R., odds ratio; n.s., non-significant.

*p<.10.

None of the predictors measured appear as significant in the analyses. Consequently, based on this sample, there is no definition for a male profile of being psychologically suitable, and consequently no definition for a donor.

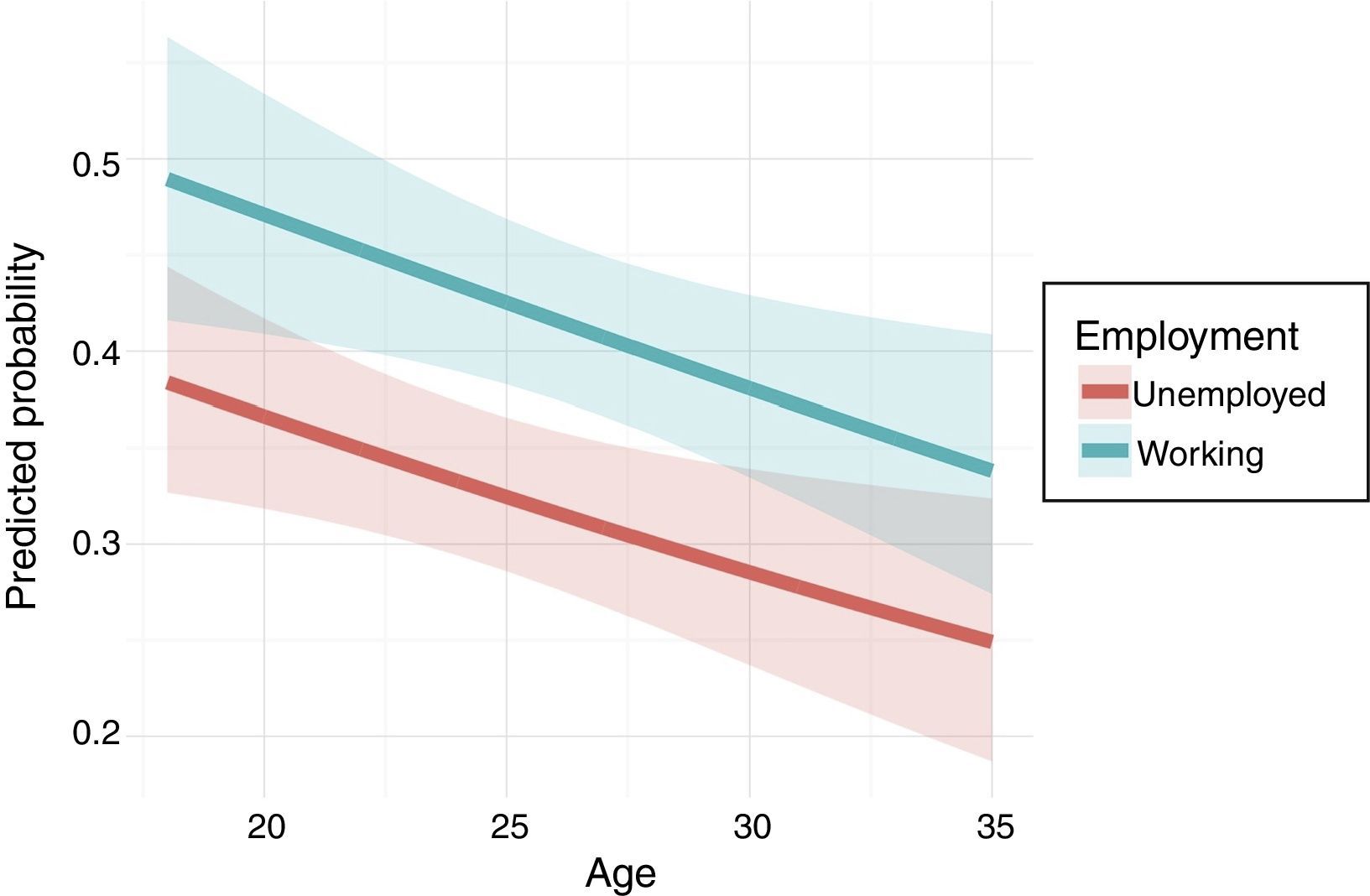

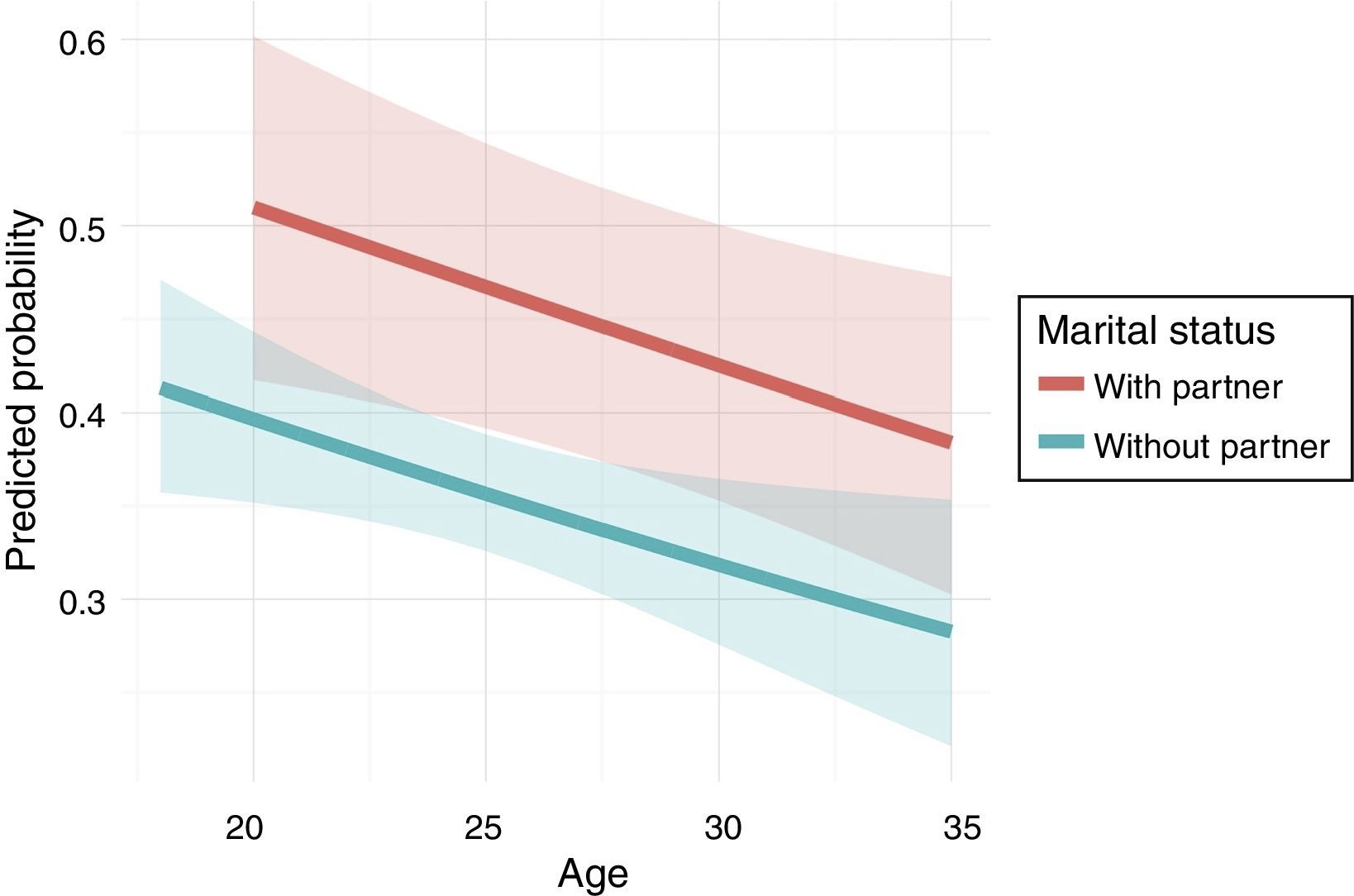

Prediction of the female donor profileThe model was estimated based on the saturated model and based on Cook's distance, 3 outliers were eliminated. Afterwards, the non-significant predictors were eliminated and interactions between them were tested. The resulting model contains 3 mutually independent predictors (see Table 1). The chi-squared test for nested models did not produce significant results between the base model and the final model (D(12)=13.64; p<.324). However, the chi-squared test for differences between our model and the null model was significant (D(3)=21.84; p<.001). With respect to the model's goodness of fit, null deviance was 1425.9 on 1079 DF and residual deviance was 1404.0 on 1076 DF. The model identifies that being younger, in active employment and having a partner increases the likelihood of women becoming donors.

Fig. 2 presents the predicted probabilities of becoming a donor with employment situation and age as predictive variables of. It can be appreciated that predicted probability increases with a decrease in age and being in active employment. Fig. 3 presents the predicted probabilities of becoming a donor with having a partner and age as predictive variables. It can be appreciated that predicted probability increases with having a partner and a decrease in age. Besides, in the 18–20 age range, it is more usual for donor candidates not to have a partner.

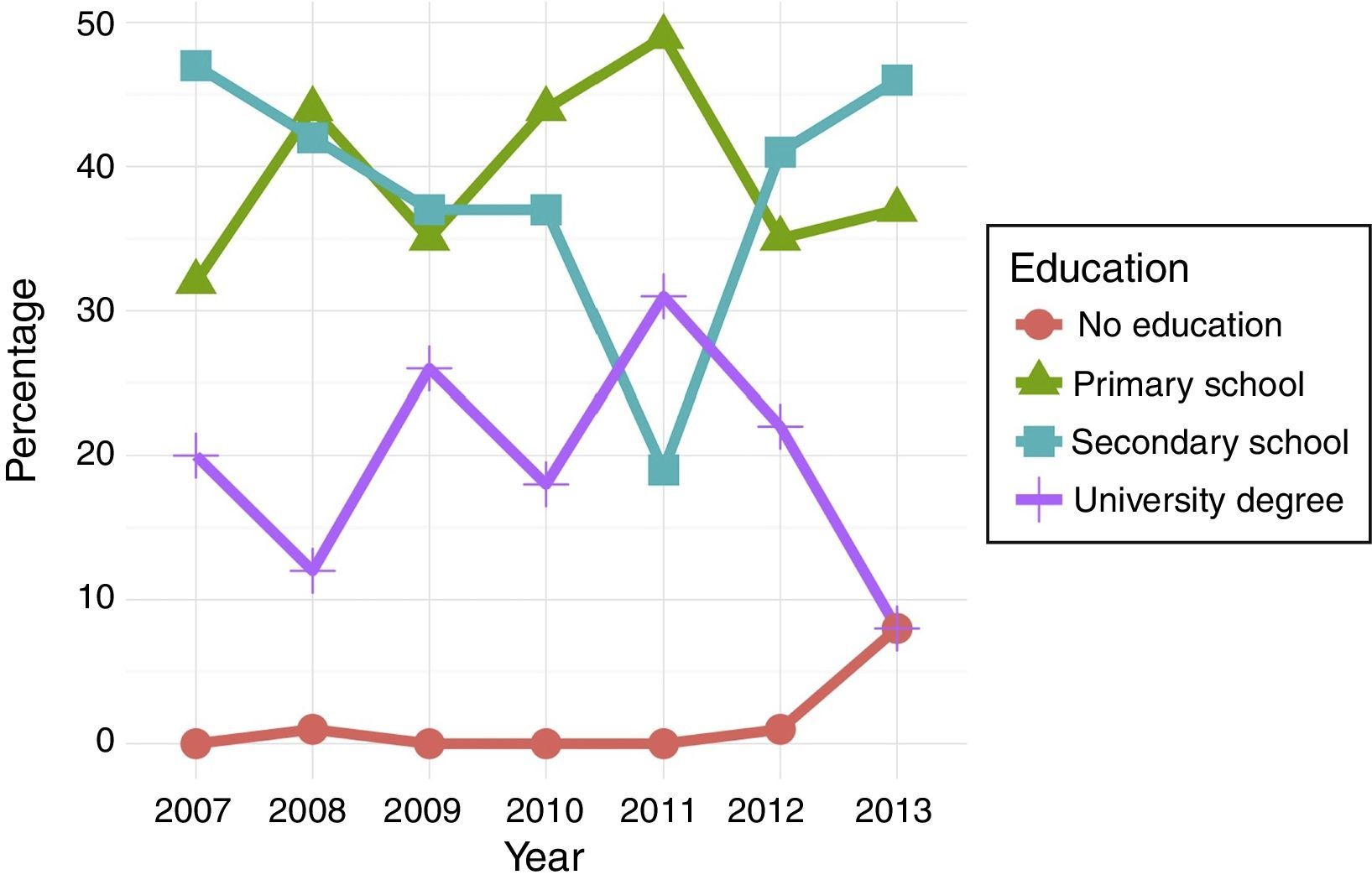

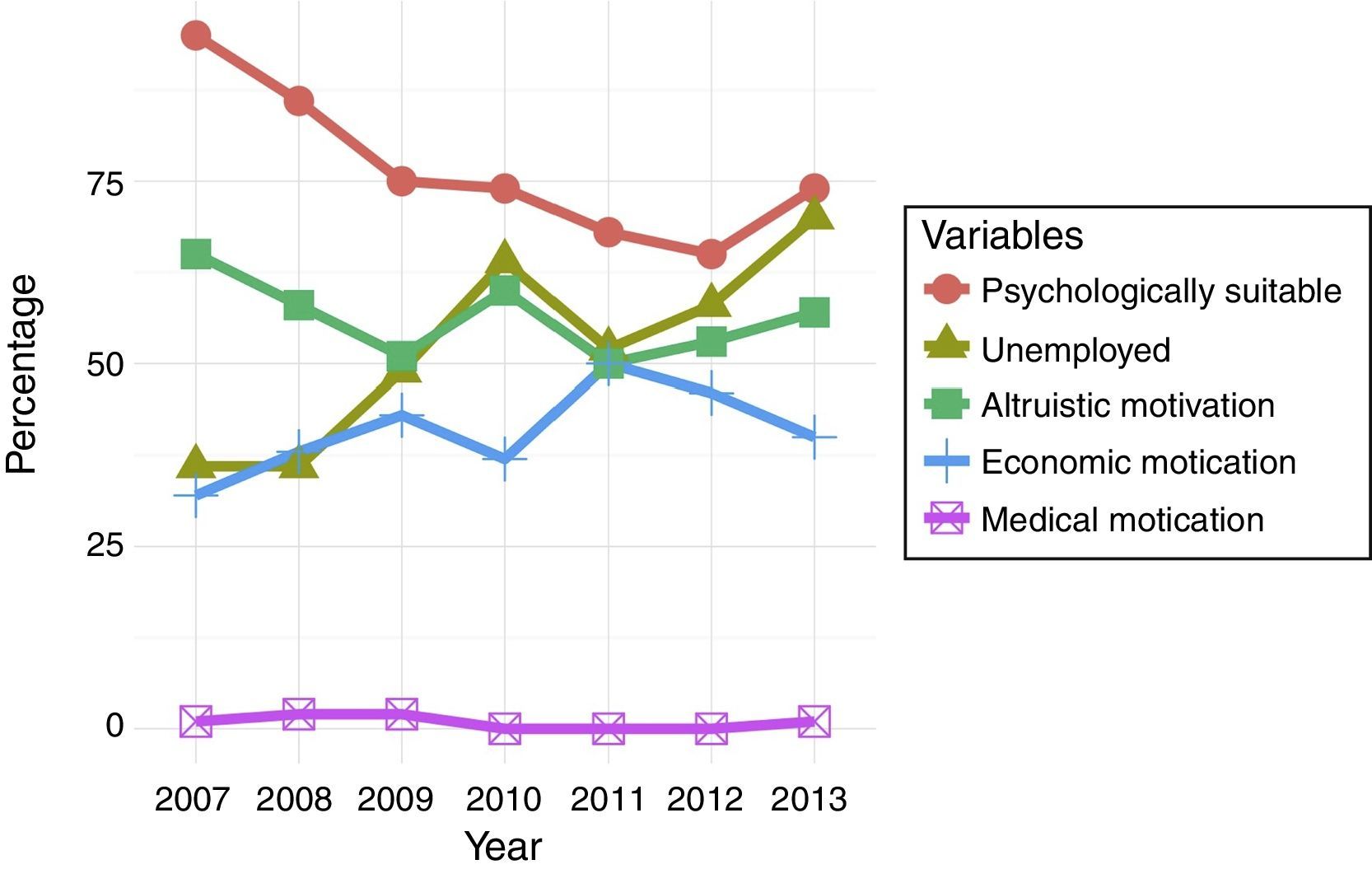

Figs. 4 and 5 show joint data of the evolution over time of the percentage of candidate donors according to level of education, being psychologically suitable, employment situation and type of motivation for donating. It can be observed that educational level is fundamentally profiled as secondary education, followed by primary education as an inverted trend in recent years. Meanwhile, the number of unemployed who want to become donors increases, but the levels of altruistic, financial and medical motivation remain the same. There is also a moderate trend toward a decrease in the number of suitable candidates in the psychological assessment.

Contingency tables – womenIn order to measure the association between each pair of variables the Pearson's chi-squared test to test independence was used.

Significant relations were found between the time variable for the 2007–2013 period (in years) and the number of women determined as suitable in the psychological assessment (χ2(6)=53.881; p<.001), education level (χ2(18)=80.302; p<.001) and being in active employment (χ2(6)=110.78; p<.001). However, this is not the case for motivation to donate (χ2(18)=18.740; p<.408). The employment situation of candidates evolves over time, where it can be observed that there is an important and significant change in candidates’ profile; from a situation in the first years where the majority were employed to recent data where the majority are unemployed.

Contingency tables – menA relation was found between the time variable and the number of men determined as suitable in the psychological assessment (χ2(5)=11.007; p=.051) (marginally significant), education level (χ2(10)=22.135; p=.014), and employment (χ2(5)=11.517; p=.042). As in the case of women there was no relation for motivation (χ2(15)=15.792; p=.395). Candidates’ employment situation evolves over time, and as in the case of egg donors, there is a clear trend toward a profile of an unemployed candidate.

DiscussionBased on the results of this study, it can be confirmed that there is an increase in the probabilities of gamete donor candidates being determined as suitable after the psychological assessment when they have a secondary or university education, work, do not smoke and have a partner. This profile makes sense within a concept where the decision to donate does not result from an impulse, and along with a partner's support when making this decision, it can be determined as favorable for donation. Apart from this, a life style which is oriented toward looking after health also complements the ideal profile for donation. Motivation, therefore, does not appear to be a key factor in candidates. Consequently our first hypothesis is not confirmed, and contrary to what it was expected, the profile is not someone who is unemployed and without a partner.

Likewise, it can be identified an increase in the likelihood of women donor candidates becoming donors when they are younger, in active employment and with a partner, whereas no profile has been found for men. Also, not having a child is not a predictor of being finally a donor in women. The configuration established between these aspects provides us with an emotional framework. Firstly, the decision is shared and supported by the partner, alleviating the responsibility of deciding alone. This, however, is a point that is not highlighted in the study by Pennings et al. (2014), but does appear in the study by Schoolcraft (2009). Secondly, being in active employment decreases the pressure of financial need arising from being unemployed. Thirdly, a higher level of education means that candidates have more access to information, more symbolic resources which allow them to use abstract thinking (like logical reasoning, inference, deductions, etc.) with greater plasticity, and it also facilitates the work of introspection on an emotional level. In this case, the results do coincide with those obtained by Pennings et al. (2014), but on the other hand, the fact that having partner and being younger favors the decision to donate contradicts results from previous studies (Sachs et al., 2010). With respect to being younger, it has to be considered that the age range covers an interval for young women, but we can infer that altruism as an ideal appears much more accentuated in younger women than mature women, who have surely had some experience where ideals have been questioned and have been rejected.

In comparison to previous studies, these findings allow us to predict who among the candidates will become donors. On the other hand, the fact that a defined profile has not been found for men could be due to the sample size, and also because no profile as such exists, since as other studies have reported there are difficulties in finding profiles in relation to, for example, their motivation (Van den Broeck et al., 2013). In which case, our second hypothesis is only partially confirmed, and no clear results appear for motivation.

It has also been observed that over time candidates profile has changed in the percentage of those determined as suitable in the psychological assessment, level of education and being in active employment, but not in the motivation for donating. That is to say, that there has been a general change in the profile for female donor candidates but it has not affected their motivations. However, as Purewal and van den Akker (2009) comment, it is more likely for candidates to talk about altruistic motivation than financial motivation in the psychological assessment, and these data remain stable. For men, it were found changes in the number of candidates determined as suitable in the psychological assessment (only marginally significant), level of education, active employment, and the same as for women, there was no change in motivation. Comparison between the female and male profiles shows that they have evolved similarly. If it is observed the evolution of the rate of unemployment in Spain (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2016), a similar relative path becomes patent to the one found in our samples. It can be considered therefore that this increase in gamete donation demand, mainly in women, has been generated in part by the economic crisis that affects Europe, and in particular Spain, where financial compensation for donation could become a way of earning money. In this respect, the third hypothesis is confirmed.

It can be concluded that being younger and in active employment and with a partner increases the probability of female candidates becoming donors. However, no specific profile has been found for male candidates. Likewise, a socio-demographic profile of donor candidates is shown to have evolved, but this has not affected motivation.

These prediction profiles mean that a fertility clinic will be able to design a more effective selection process for donor candidates, taking better advantage of the resources available to them and decreasing the index of treatment leaving.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that no human or animal experiments have been performed for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the correspondence author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would particularly like to express their gratitude to Dr. Gemma Benavides for her disinterested revision of the draft of this manuscript.