Orientation in time (OT) is frequently assessed in the examination of patients’ mental state, and especially in cognitive impairment screening.1,2 In a previous study, our group reported a new technique for the assessment of OT, which used an open question (“please tell me today's date as accurately as possible”) and quantified the spontaneous responses of the patient by adding the scores on 2 scales: a semantic scale scoring the date data provided by the patient (day [D], month [M], year [Y], and day of the week [W]); and an episodic scale, scoring the correct episodic information for each field.3

When using an open question, it is very frequent for patients to give spontaneous responses limited to the elements of date from the yearly calendar (D-M-Y), either providing all of them (D-M-Y) or different combinations of elements, and with different degrees of certainty, speed, and accuracy with regards to the associated episodic information. For example, for an examination taking place on 2 February 2015: “Today?... It is the second?,... Yes, the second!” (isolated D); “Today?... Yes, yes, the second of February!” (D-M); or, for example, “Today?... The third?..., No, no, isn’t it the second?... the second of February 2015!...” (D-M-Y). However, the day of the week (W) is rarely provided spontaneously. In fact, the Benton temporal orientation test includes a specific item asking about the day of the week (W).4 In clinical practice, patients rarely provide data on this item (W), so that when the information (D-M-Y) is provided quickly and correctly at the episodic level, the rater should consider whether to “approve” the item (W) by assigning the score, or ask about it.

In order to analyse knowledge of W in the OT assessment, we conducted an observational study of 60 patients with suspected very mild to moderate cognitive impairment (GDS 2-3-4) from our department's records.5 The selection criterion was spontaneous response to the prompt “please tell me today's date as accurately as possible” which included correct episodic information on the items D-M-Y only, provided in any combination (D-M-Y; D-M; D; others), and not including W, so that the rater asked about it specifically and episodic information about W was available. Each group (D-M-Y; D-M; D; other combinations) was subdivided into 2 categories, according to the quality of the episodic recall: (A) fast and correct, and (B) increased latencies and/or self-corrected mistakes. Data were analysed with version 22 of the SPSS statistical software for Mac.

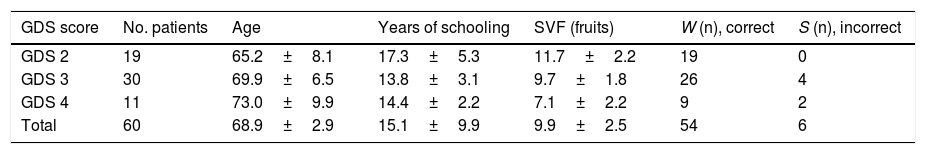

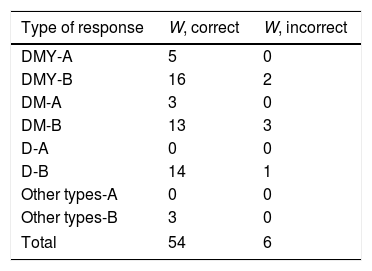

Table 1 shows the distribution of GDS scores in the sample (24 men and 36 women) with significant differences for age, years of schooling, and semantic verbal fluency (fruits) (F statistic for ANOVA, 4.3; P<.01), and for correct and wrong responses to the question about W (χ2=37; P<.001). Table 2 shows the distribution of responses about W according to the items provided and the quality of episodic recall. We observed that knowledge of W is clearly associated with the quality of episodic recall (χ2=53; P<.0001).

Distribution of GDS score groups by age, years of schooling, semantic verbal fluency, and distribution of responses about day of the week.

| GDS score | No. patients | Age | Years of schooling | SVF (fruits) | W (n), correct | S (n), incorrect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDS 2 | 19 | 65.2±8.1 | 17.3±5.3 | 11.7±2.2 | 19 | 0 |

| GDS 3 | 30 | 69.9±6.5 | 13.8±3.1 | 9.7±1.8 | 26 | 4 |

| GDS 4 | 11 | 73.0±9.9 | 14.4±2.2 | 7.1±2.2 | 9 | 2 |

| Total | 60 | 68.9±2.9 | 15.1±9.9 | 9.9±2.5 | 54 | 6 |

GDS: Global Deterioration Scale; SVF: semantic verbal fluency; W: day of the week.

Distribution of correct/incorrect responses to the specific question about day of the week, according to the type of response to the open question on date.

| Type of response | W, correct | W, incorrect |

|---|---|---|

| DMY-A | 5 | 0 |

| DMY-B | 16 | 2 |

| DM-A | 3 | 0 |

| DM-B | 13 | 3 |

| D-A | 0 | 0 |

| D-B | 14 | 1 |

| Other types-A | 0 | 0 |

| Other types-B | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 54 | 6 |

A: fast and correct response; B: recall with increased latencies of responses and/or self-corrected mistakes; D: only provides day; DM: provides day and month; DMY: provides day, month, and year; Other types: provides other combinations (e.g., M-Y or D-Y); W: day of the week.

These data suggest that if the patient's responses for D-M-Y are of good quality in terms of episodic recall, knowledge of W is adequate. On the contrary, if episodic recall of D-M-Y is of poorer quality, responses about W have a significantly higher frequency of mistakes. In conclusion, we may only approve an implicit episodic knowledge of W in cases with fast, correct responses regarding the D-M-Y items, even if patients do not provide information on W spontaneously.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Turrado T, Velázquez Benito A, Tejero Juste C, Pascual Millán LF. El día de la semana en la exploración de la orientación en el tiempo. Neurología. 2018;33:416–417.