Pseudotumoural lesions simulate central nervous system tumours in clinical and radiological evaluations.1–3

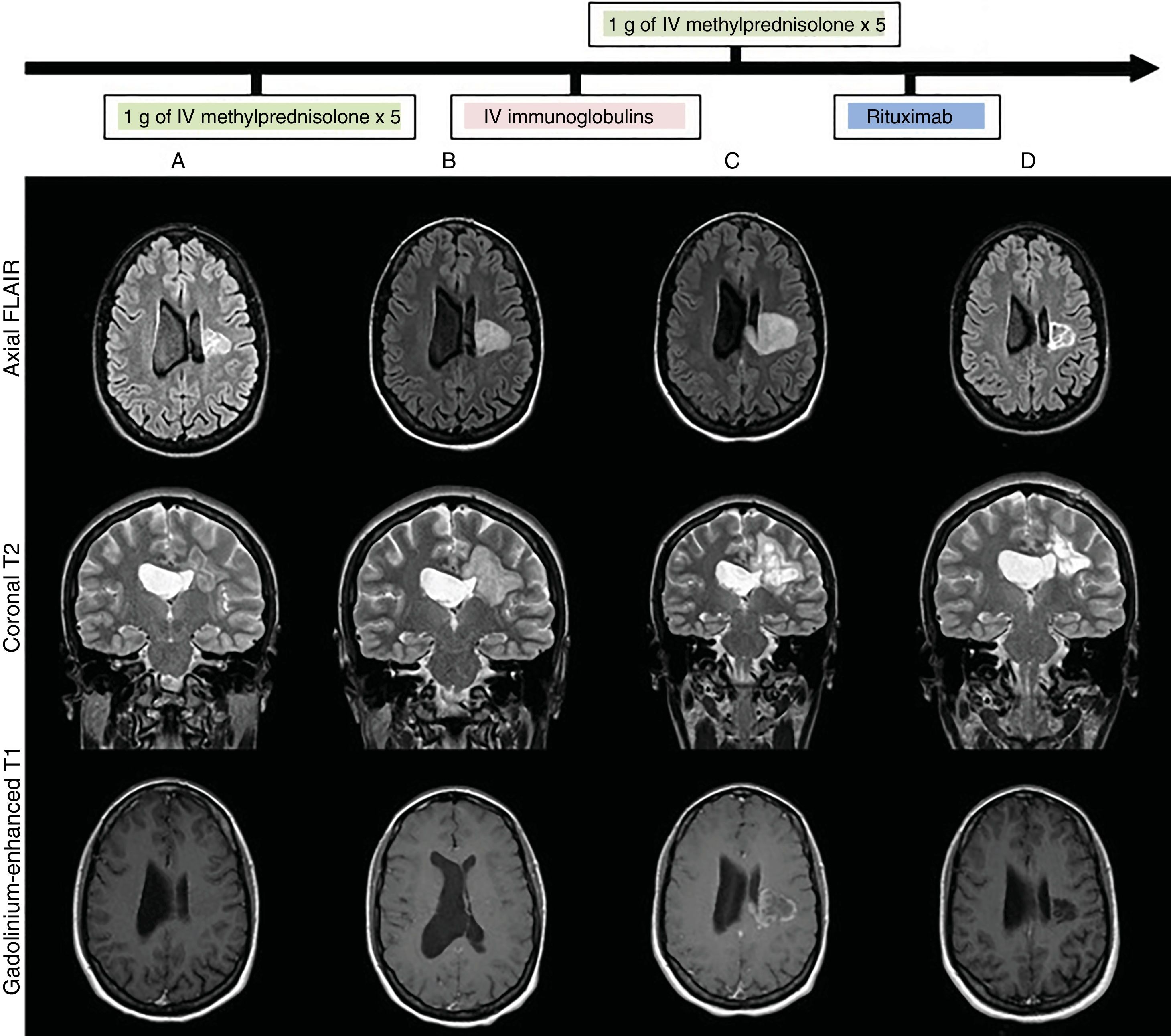

We present the case of a 28-year-old woman with no relevant history who attended our department due to subacute, progressive onset of right hemiparesis and dysarthria as the clinical manifestations of a pseudotumoural lesion. A baseline MRI study (Fig. 1) showed a heterogeneous lesion affecting the left corona radiata and centrum semiovale, with no perilesional oedema, mass effect, or gadolinium uptake. Blood analysis, lumbar puncture (with oligoclonal banding), blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures, CT scan, full-body PET/CT, and echocardiography yielded normal or negative results. We requested an immunodeficiency and autoimmunity study (systemic, anti-neuromyelitis optica antibodies, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies, onconeuronal antibodies, and neuronal surface antibodies), PCR to detect VZV and HSV in CSF, serology tests for HIV, HCV, HBV, CMV, syphilis, Toxoplasma gondii, and Borrelia burgdorferi; QuantiFERON®; and PPD skin test, all results were negative. After ruling out infectious causes, and having obtained radiological data suggesting an inflammatory pseudotumour, we started immunosuppressive treatment (Fig. 1B,C), administering 2 pulses of 1 g of intravenous methylprednisolone and one cycle of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg). After 5 weeks, with no therapeutic response and continuing clinical and radiological progression (Fig. 1C) (increased lesion size and contrast uptake), a brain biopsy (Fig. 2) showed findings compatible with an inflammatory demyelinating process,1,4 with no histological data of malignancy. Treatment with rituximab achieved progressive clinical improvement. A brain MRI scan (Fig. 1D) performed one month later showed decreased lesion size and no contrast uptake. The patient was discharged with a diagnosis of inflammatory pseudotumour. She remains under follow-up by the neurology department, and at the time of publication has presented no further episodes.

Brain MRI: lesion progression (FLAIR, T2-weighted, and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequences) at admission (A), after treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone (B), after treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins (C), and after treatment with rituximab (D). Heterogeneous lesion with grouped/confluent hypoechoic rims (A and B), progressing to cystic-malacic areas (C and D), affecting the left corona radiata and centrum semiovale with extension to the corpus callosum. Maximum diameter of 3cm at admission (A), increasing to 4.1cm despite treatment (C), and subsequently decreasing to 3cm after treatment with rituximab (D). No perilesional oedema or mass effect. No enhancement after contrast administration at admission (A), with subsequent intra-and perilesional patchy contrast uptake despite administration of corticosteroid and immunoglobulins (C); contrast uptake disappeared after treatment with rituximab (C).

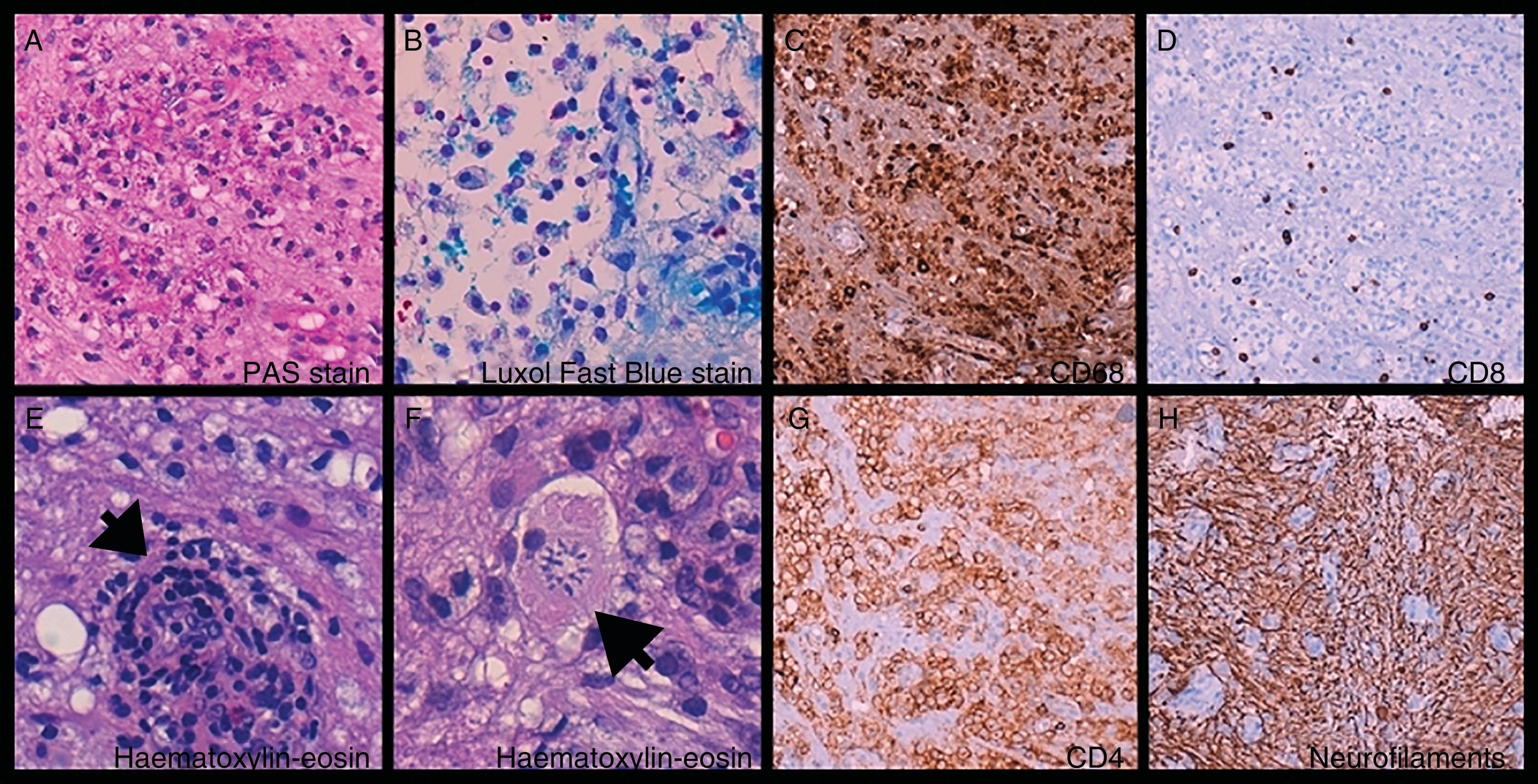

Brain biopsy: foamy histiocytes (A, B, and C) ([C] CD68+) filled with phagocytosed myelin ([A] PAS-positive and [B] Luxol Fast Blue–positive material) and T-cells (D and G) ([D] CD8+ and [G] CD4+), mixed with astrocytes and Creutzfeldt cells (reactive astrocytes [F, arrow]). Perivascular cuffing (E, arrow). Preserved axonal network (H).

Inflammatory pseudotumour is a rare condition (0.3 cases/100 000 person-years5,6). Differential diagnosis includes infection, neoplasia, and vascular disorders.1,3 Certain clinical and radiological characteristics support diagnosis,1,2,6 whereas biopsy is used only for atypical or refractory lesions.6 Several cases have been reported of patients who showed no response to corticosteroids but were responsive to other immunosuppressive treatments,5–7 with IVIg, plasmapheresis,8 rituximab,7,9–12 or cyclophosphamide.7 Ours is the first case in the literature of rituximab being used after IVIg to treat a corticosteroid-refractory pseudotumoural lesion, and the seventh case of rituximab being used after plasmapheresis.

The lack of treatment response is therefore considered to go beyond the absence of response to corticosteroids, in clinical practice, it is difficult to decide when to perform a brain biopsy in cases of refractory pseudotumoural lesions. Furthermore, biopsy may show inflammation and demyelination,1,4 although it rarely enables us to differentiate between onset of multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica, and focal forms of monophasic encephalitis that will not progress to a chronic demyelinating disease,1,3,13 close, prolonged clinical follow-up is therefore essential.

We established diagnosis of focal, monophasic autoimmune encephalitis, given the isolated pseudotumoural lesion of inflammatory aetiology (which was confirmed by an anatomical pathology study), with negative oligoclonal bands, of monophasic course (to date) and responsive to treatment with rituximab (supporting immune-mediated pathogenesis with B-cell involvement).

In conclusion, some autoimmune lesions cannot be identified with a known serological marker and represent a diagnostic challenge. Focal, monophasic autoimmune encephalitis may explain this case and other cases of isolated inflammatory pseudotumoural lesions in patients with no previous diagnosis of chronic demyelinating disease, showing a monophasic course during follow-up.

We would like to thank Dr Laura Zaldumbide Dueñas (anatomical pathology department, Hospital Universitario de Cruces), who performed the anatomical pathology study of the brain biopsy sample and provided the corresponding images.

Please cite this article as: Moreno-Estébanez A, et al. Lesión seudotumoral desmielinizante aislada: ¿encefalitis focal monofásica autoinmune? Neurología. 2020;35:217–219.

![Brain biopsy: foamy histiocytes (A, B, and C) ([C] CD68+) filled with phagocytosed myelin ([A] PAS-positive and [B] Luxol Fast Blue–positive material) and T-cells (D and G) ([D] CD8+ and [G] CD4+), mixed with astrocytes and Creutzfeldt cells (reactive astrocytes [F, arrow]). Perivascular cuffing (E, arrow). Preserved axonal network (H). Brain biopsy: foamy histiocytes (A, B, and C) ([C] CD68+) filled with phagocytosed myelin ([A] PAS-positive and [B] Luxol Fast Blue–positive material) and T-cells (D and G) ([D] CD8+ and [G] CD4+), mixed with astrocytes and Creutzfeldt cells (reactive astrocytes [F, arrow]). Perivascular cuffing (E, arrow). Preserved axonal network (H).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735808/0000003500000003/v1_202005131017/S2173580819301294/v1_202005131017/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)