Cerebral infarcts are the third most common cause of death in Spain and the leading cause of physical disability in adults. Twenty-five per cent of all strokes occur in people younger than 65.1,2 Cardiac tumours are a very rare disease with an incidence that ranges from 0.001% to 0.28% in post-mortem studies. Half of such tumours are of myxomatous origin. They are an infrequent cause of cerebral embolism and account for less than 1% of all strokes.3 Although they are rare, they must be considered in the differential diagnosis of all young patients with cerebral ischaemia. We present the case of a patient who experienced acute neurological deficit and prior episodes of transient cerebral ischaemia.

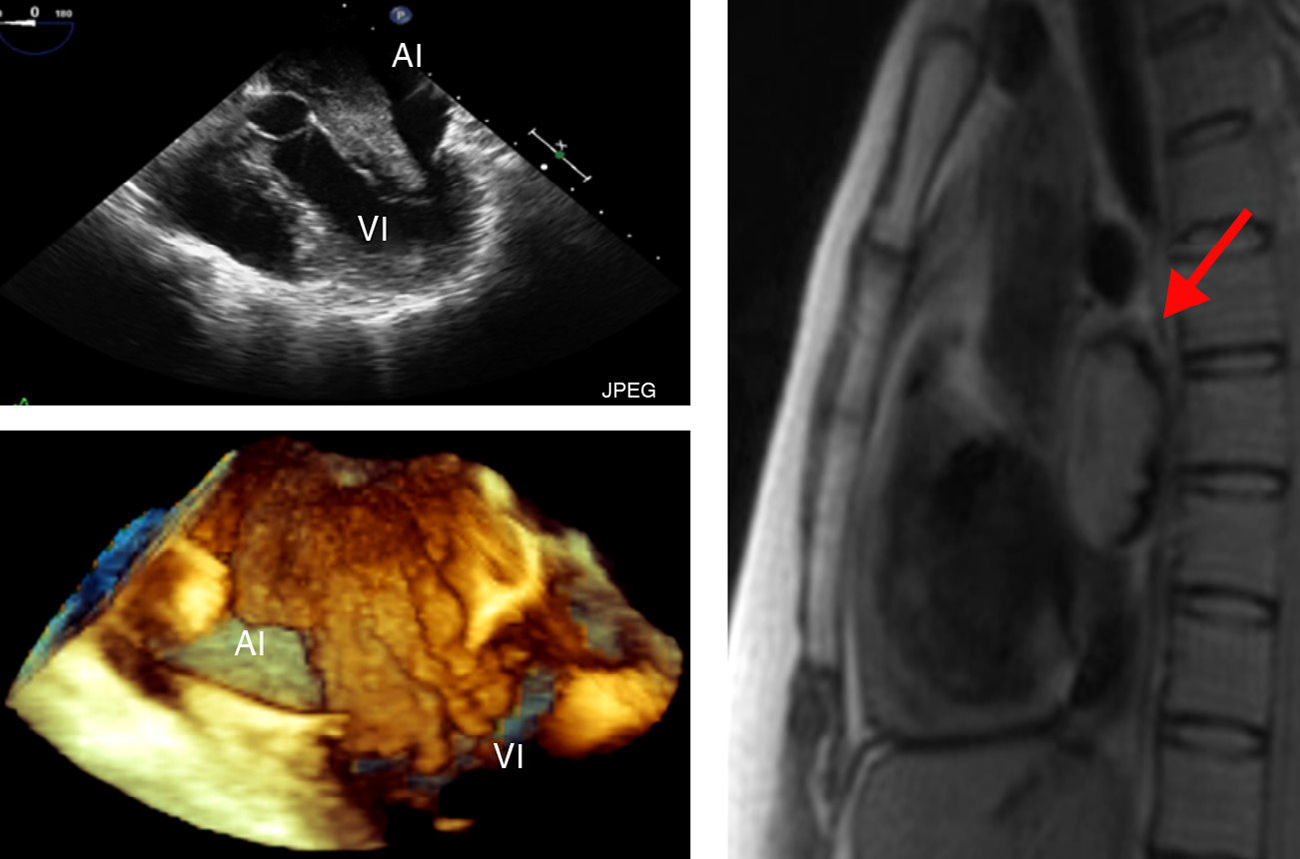

Female patient aged 33 with a personal history of depressive syndrome and chronic anaemia that remained uncorrected after treatment with ionic iron. The patient came to the hospital due to a 2-hour transient episode of diplopia. She reported having had a similar episode previously. Upon arrival at the hospital, the patient presented no neurological symptoms. However, the examination revealed significant purpuric lesions on the thighs and crura, and on the distal parts of the upper limbs. During her stay in the emergency department, doctors performed laboratory tests, an ECG, and a cranial CT, none of which revealed pathological findings. Once the patient was admitted, doctors began the procedure described below for diagnosing stroke in young patients. (a) Haematological analysis, which revealed chronic anaemia disease with an increase in acute-phase reactants; immunology study (ANAs, ANCAs, anti-DNA, anticardiolipin and antiphospholipid, anti-Ro, anti-La, rheumatoid factor, and anti-ACh receptor antibodies) and hypercoagulation study (all results negative); (b) lumbar puncture showing absence of oligoclonal bands and negative Link and Tibbling index; (c) brain MRI showing old ischaemic lesions in cerebellar hemispheres; (d) vascular cerebral study by means of CT angiogram and neurosonology that revealed no significant haemodynamic disorders; (e) transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with a subsequent transoesophageal approach (TEE) showing a mass of 11cm2 in the LA that suggested atrial myxoma (Fig. 1); (f) heart MRI confirming the presence of a mass with irregular contours in the LA; and (g) biopsy of the cutaneous lesions, which showed intravascular thrombi consisting of angiomyomatous tissue.

The images in the first column were taken with TEE; above, 2D image showing 5 cavities and below, 3D image showing full volume. Both images reveal a mass with irregular contours on the LA that enters the LV during diastole. The image in the second column is a cardiac MRI slice showing an intra-atrial mass (arrows).

Despite prophylactic treatment with anticoagulants, the patient presented a new episode of cerebral ischaemia during the diagnostic process. The episode was characterised by right-sided paraesthesia that lasted 30minutes before resolving completely. Doctors resected the mass which was of myxomatous origin according to the histological study. Subsequent check-ups performed by the outpatient cardiology unit indicate that the patient has had no clinical or echocardiographic signs of a relapse.

Atrial myxoma is a benign tumour which mainly affects women (2:1) aged between 30 and 60. Although these tumours mainly arise sporadically, 7% of all cases have a familial component. Up to 10% of the cases may be asymptomatic, while the rest may present symptoms through 3 basic mechanisms: (a) mitral valve obstruction with symptoms of dyspnoea, heart failure or sudden death; (b) constitutional symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or weight loss which may be related to interleukin 6 synthesis by the tumour; and (c) embolic phenomena in peripheral organs.4–6 Neurological symptoms are present in between 26% and 45% of the patients, with cerebral infarct being the most prevalent condition.6–9 Researchers have described completely asymptomatic cases of ischaemic lesions of different sizes and location that were detected by brain MRI.10 Symptoms resulting from tumour infiltration are less common; researchers have described intracranial aneurysms which are secondary to the infiltration of the vascular wall, as well as tumours secondary to the parenchymatous infiltration. Neurological follow-up is therefore advisable, since these complications can occur years after resection of the tumour.7,11

Diagnosis is based on the echocardiogram, which has a diagnostic sensitivity of 100% according to different series.7 The transoesophageal approach is the technique of choice as it provides a better view of the atrium and enables detection of smaller tumours.12 Cardiac MRI may be useful, considering that ultrasound sometimes presents false negatives, underdiagnoses the extension of the tumour, or offers limited information about its type.7 Additional tests, such as a cutaneous biopsy revealing angiomyomatous tissue in the capillary lumen, may help doctors establish a diagnosis.13

In a case of suspected cardiac myxoma, surgical resection should be performed as soon as possible given the high risk of recurring embolic phenomena.4,14,15 When surgery is scheduled, secondary prevention may be a matter of debate. The use of antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy has been recommended due to the embolic nature of this disease, but there is no consensus regarding the use of these drugs,7 and embolic relapses may occur despite treatment.8

Recurrence of myxoma has been observed in between 2% and 5% of the sporadic cases and in 22% of the familial cases.7,8 Therefore, researchers recommend a yearly echocardiographic study during the first 3 or 4 years,3,5 even if there are no guidelines on this topic.

Please cite this article as: González-Suárez I., et al. Focalidad neurológica como primera manifestación de un mixoma cardiaco. Neurología. 2013;28:384–5