Percutaneous sacral nerve stimulation with implantable electrodes is currently one of the most promising treatments for the management of neurogenic bladder,1 while transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been shown to be effective for treating idiopathic overactive bladder.2–4 Our group recently reported on the effectiveness of TENS administered at home for paediatric patients.5 Transverse myelitis is a very rare cause of neurogenic bladder in children, with myelodysplasia being the most frequent cause.1 The good outcomes observed with TENS administered at home to treat idiopathic overactive bladder led us to consider its use in paediatric patients with neurogenic bladder not caused by myelodysplasia.

We present the case of an 8-year-old girl treated over the last 5 years at our hospital’s paediatric urodynamics unit due to neurogenic bladder secondary to transverse myelitis, with onset at 2 years of age. Prior to the onset of transverse myelitis, she presented adequate bladder and bowel control, having completed toilet training. Sequelae included absence of deep tendon reflexes in the lower limbs, urinary incontinence, recurring urinary tract infections, and constipation with encopresis. At 5 years of age, she was referred to our unit due to persistence of the urinary symptoms and bowel incontinence.

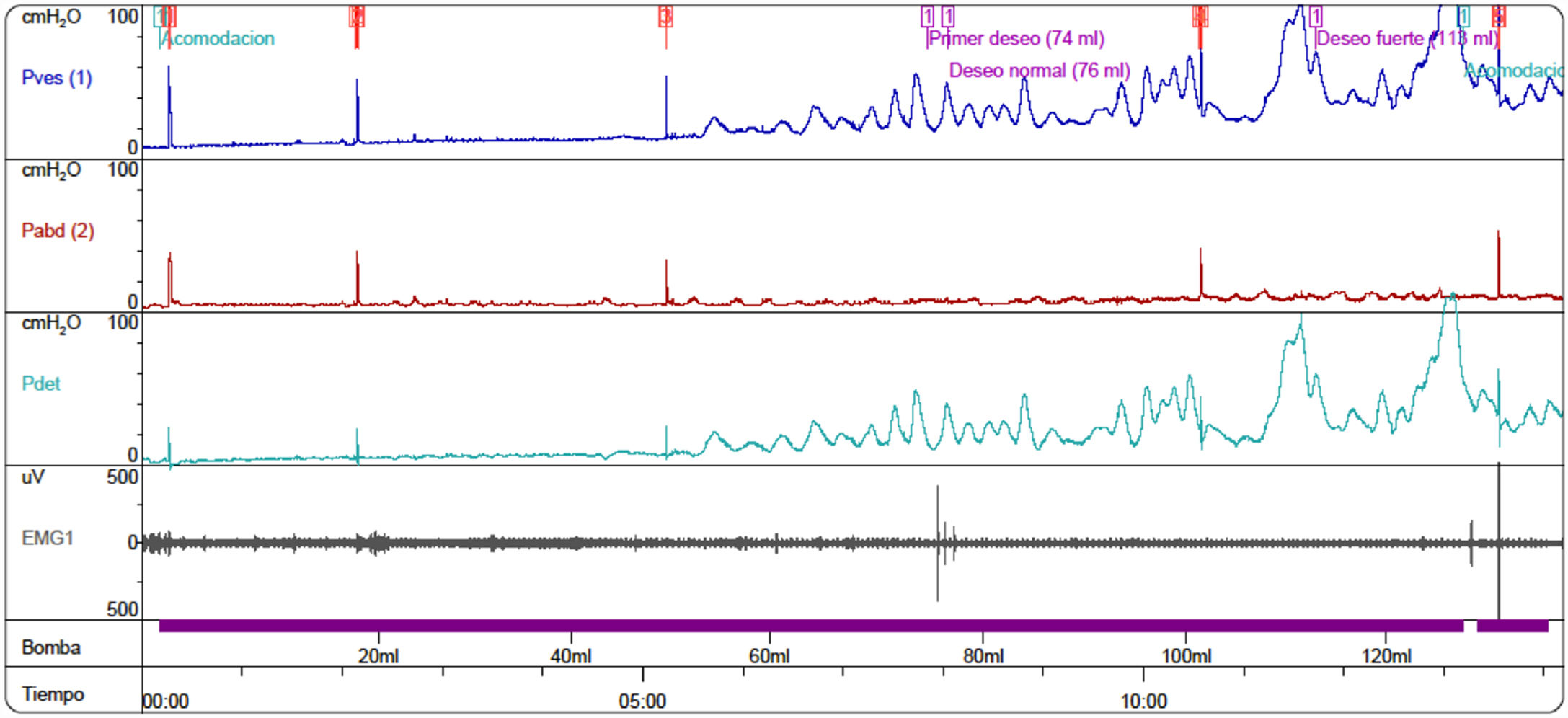

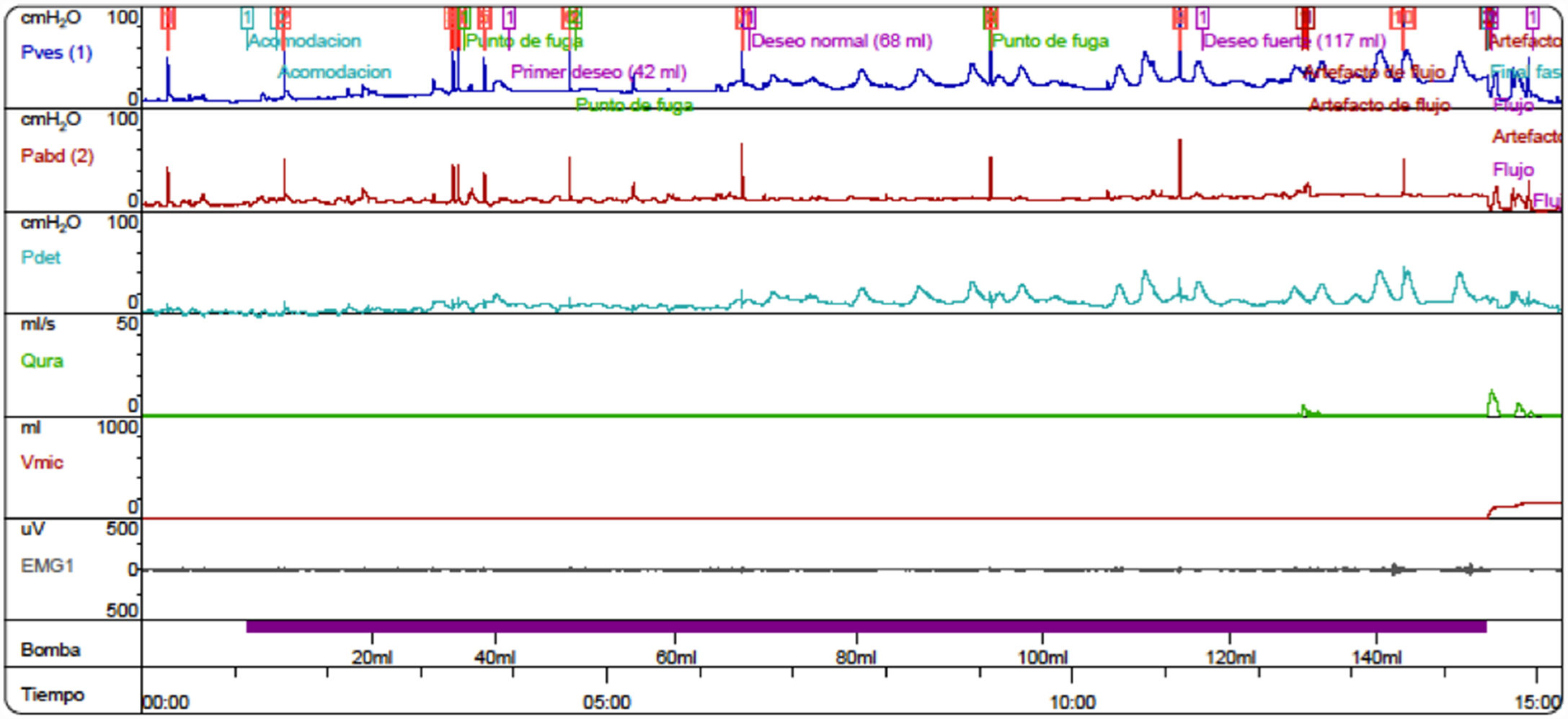

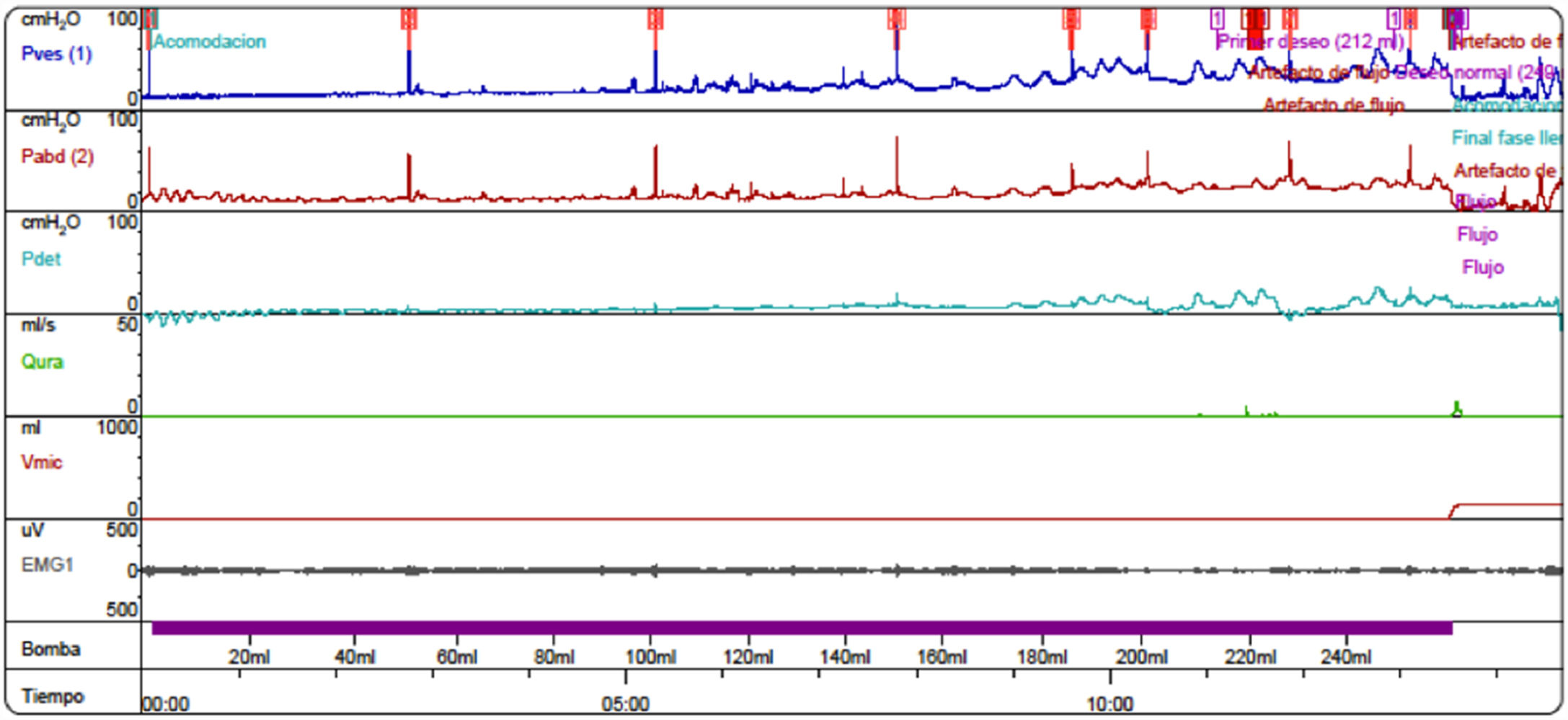

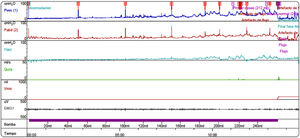

After proper management of the bowel symptoms, we performed urodynamic testing and evaluated the severity of urinary symptoms using the Paediatric Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Score (PLUTSS; range 0–34).6 A cystometry study revealed bladder capacity of 90 cc (expected capacity for her age: 240 cc); detrusor hyperreflexia with contractions of 100 cm H2O, causing leakage; detrusor sphincter dyssynergia; and considerable urinary retention (Fig. 1). The patient scored 28 points on the PLUTSS. Treatment was started with anticholinergic drugs (oxybutynin) and intermittent urinary catheterisation, and the patient showed slight improvements in urodynamic parameters (functional bladder capacity [FBC] of 120 cc, and hyperreflexive contractions at 70 cc of filling with 50 cm H2O of detrusor pressure) and clinical symptoms (PLUTSS = 27) (Fig. 2); no changes were observed one year after treatment onset. Due to refractory detrusor hyperreflexia, we proposed that TENS be added to the anticholinergic treatment before resorting to surgical treatment (enterocystoplasty or botulinum toxin injection). The family were trained to apply the stimulator (UroSTIM 2.0) to the sacrum (S2-S3) during consultations at our unit. Current was applied with a frequency of 10 Hz and a wavelength of 200 s. Intensity was regulated on a daily basis according to the maximum intensity tolerated without pain. Daily 20-minute sessions were performed while the patient was eating dinner or watching television. After 3 months of treatment, cystometry results (FBC = 240 cc, without leaks during filling; low-amplitude contractions; Fig. 3) and symptoms had improved (PLUTSS = 3).

TENS presents a high level of evidence for the treatment of paediatric idiopathic overactive bladder,7 as shown by urodynamics study findings8; however, few studies have addressed its effectiveness for neurogenic bladder. Patients with myelodysplasia presenting lumbosacral involvement are ruled out as candidates for TENS; however, we believe the technique may be considered a non-invasive therapeutic option for neurogenic bladder secondary to transverse myelitis. Initial treatment response in our patient was very good, although these favourable results must be confirmed with long-term follow-up.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Somoza Argibay I, Casal-Beloy I, Seoane Rodríguez S. Neuroestimulación eléctrica transcutánea (TENS) en vejiga neurógena secundaria a mielitis transversa. Neurología. 2021;36:86–88.