Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a health problem of the first magnitude, both due to its high prevalence and its high morbidity and mortality, exerting a high impact on our health system.1 This disease is among the top ten causes of mortality and disability combined,2 which has motivated multiple organizations and societies to focus their efforts on improving and standardizing its management.3

Despite the fact that COPD management guidelines indicate that spirometry is an essential requirement to reach a diagnosis of this disease,3 the truth is that it is a test that continues to be underused today. The limited availability of equipment, the lack of human resources, the difficulties in transporting the patient to a health center or the excessive waiting time for respiratory tests to be performed,4,5 are some of the reasons that can lead to a doctor to start an inhaled treatment “empirically”, without having a confirmatory spirometric result. In studies carried out before the pandemic, it was shown that up to half of the patients who had received a diagnosis of COPD without a confirmatory spirometry were receiving treatment for their probable respiratory pathology,6 a practice that probably reached its maximum expression during the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, multiple organizations limited, or even prohibited, the performance of lung function tests, with the intention of reducing the transmission of the SARS-COV2 coronavirus. The accumulated delay generated by the closure of the lung function laboratories in that period, the slow recovery of the use of spirometry in health centers, especially in Primary Care, the high pressure of care, and very probably therapeutic inertia, places us in a unfortunate scenario where the usual clinical practice is to empirically start inhaled therapy in a smoker patient with symptoms of dyspnea, cough or chronic expectoration, pending a confirmatory test. However, this practice is not free of criticism and possible complications (adverse effects related to medication, increased health costs or environmental impact).7

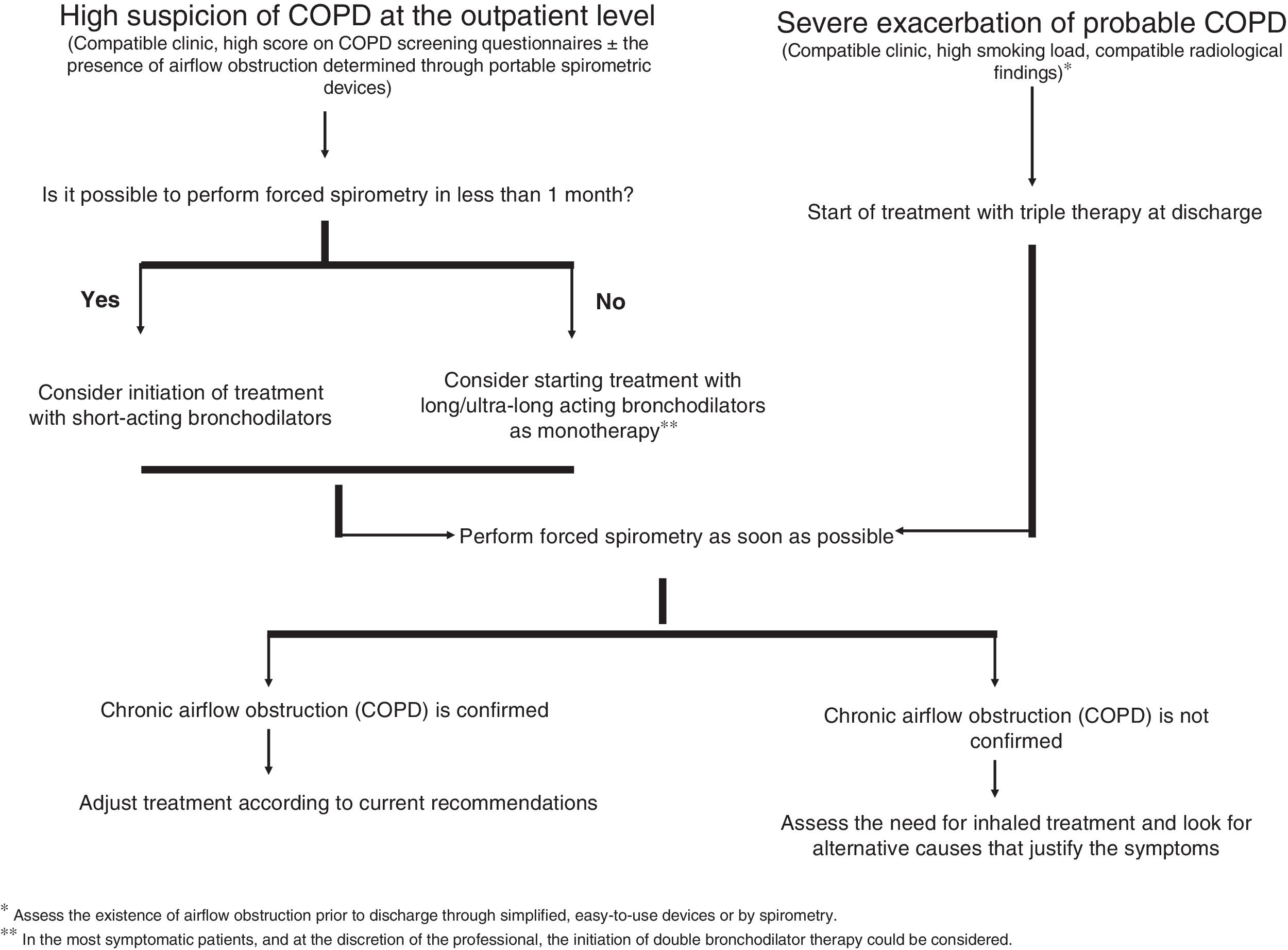

Aware of this and with the intention of bringing some order to this situation, the recent publication of “Referral criteria for COPD. Continuity of care” incorporates this scenario in its diagnostic management algorithm.8 A situation that we believe is advisable to reflect on in an attempt to achieve an acceptable risk-benefit balance, pending an improvement in the accessibility of spirometry with a relatively short waiting time. Thus, when COPD is suspected, we can basically have two scenarios (Fig. 1): (1) a sufficiently relevant respiratory infection that requires hospital admission in a patient with a high tobacco burden and with clinical and/or radiological data suggestive of COPD and (2) a situation of stability in which the patient, habitually a smoker or ex-smoker, goes to his Primary Care doctor referring symptoms compatible with COPD. In the first case, various studies suggest that up to 70% of cases discharged from the hospital with a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation (without spirometric confirmation) show chronic airflow obstruction.9 Being aware of the high probability that the diagnosis will be confirmed in these patients, that the priority is to avoid readmission given the impact that this process has on the patient, and after having weighed the risk/benefit of starting treatment without a clear diagnosis, the initiation of inhaled therapy could be justified, considering triple therapy (LAMA/LABA/ICS) as the most reasonable option in this scenario until spirometric confirmation. This proposal is supported both by the extensive evidence that describes the benefit of inhaled corticosteroids in the prevention of exacerbations, and by the data obtained from the PRIMUS study,10 which shows that the delay in the start of triple therapy after an admission due to an exacerbation of COPD, the possibility of a new exacerbation increases and increases healthcare costs. Assessing the existence of an airflow obstruction prior to discharge through simplified devices that are easy to use or by spirometry,11,12 tools that are relatively accessible in the hospital care setting, can help us to guide the diagnosis, allowing us to know if the chosen therapeutic option is valid. In the second scenario, the situation is more complex, with a prevalence of COPD in subjects that we can call at risk (smokers or ex-smokers with respiratory symptoms) that ranges between 10 and 35%.13

As emphasized in different documents, the diagnosis of COPD should not be based exclusively on the presence of symptoms, since it is still an aspect that depends on the patient's perception.3 In addition, some factors such as advanced age, obesity or the presence of comorbidities, especially those of a cardiovascular nature, as closely linked to smoking as to COPD itself, can also influence the symptoms. That is why, in the situation of a patient with a history of smoking and respiratory symptoms, the evaluation of symptoms must be exhaustive, and other alternative factors that could infer and justify the patient's clinical situation must be weighed.

A high score in questionnaires validated as a COPD screening tool, such as the COPD-PS (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-population screener; score ≥3), together with data suggestive of airflow obstruction in portable devices such as the Vitalograph. COPD-6, could help profile in which patients14 bronchodilator therapy could be started empirically until a confirmatory test is obtained. Although in the exceptional case that there is a short delay in performing a spirometry (<1 month), the use of short-acting bronchodilators could be considered, in those cases with a longer delay, and being cautious when reducing the appearance of adverse effects, we recommend starting monotherapy treatment with a bronchodilator (mainly with a long-acting or ultra-long-acting anticholinergic) until spirometric confirmation. However, in the most symptomatic patients, and at the discretion of the professional, the initiation of double bronchodilator therapy could be considered, especially in those subjects with a high smoking load and with radiological data of emphysema and low body mass index.15 In our opinion, the use of inhaled corticosteroids should be avoided until the diagnosis is confirmed, unless there is a previous diagnosis of asthma, assessing their subsequent indication according to current recommendations.3

In conclusion, and without being exempt from criticism, our proposal aims to bring order to a situation that has unfortunately become common. This is a little-known scenario that we must face, and on which we intend to shed some light. Although the empirical prescription of a bronchodilator treatment is intended to be a temporary “patch” to a problem of accessibility to spirometry, said prescription should not be delayed over time. Forced spirometry must be performed as soon as possible to confirm the diagnosis.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have read and approved submission of the manuscript, and all fully qualify for authorship.

FundingThe authors declare that no funding was received for this article.

Conflicts of interestMarco Figueira-Gonçalves has received honoraria for speaking engagements and funding for conference attendance from Laboratories Esteve, MundiPharma, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Rovi, GlaxoSmithKline, Chiesi, Novartis, and Gebro Pharma.

Javier de Miguel-Díez has received honoraria and funding from Laboratories AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer, Chiesi, Esteve, FAES, Ferrer, Gebro Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Menarini, MundiPharma, Novartis, Roche, Rovi, Teva and Pfizer.

Jesús Molina París has received, in the last 3 years, funding from the pharmaceutical industry, scientific societies and health management to carry out the following professional activities related to the exercise of his profession: (a) attendance at meetings: AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, semFYC; (b) speaker fees in workshops and talks: AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Primary Care Management, GSK, Menarini, semFYC; (c) participation in research and advice: AstraZeneca, Primary Care Directorate, GSK, Pfizer, semFYC.

José Miguel Valero Pérez has received fees from GSK, AstraZeneca, Menarini, Teva, Chiesi and Bial for scientific, training and research work.

Alberto Fernández-Villar has received honoraria, in the last 3 years, for lecturing, scientific consulting, participating in clinical studies, or writing publications for (alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, and Menarini.