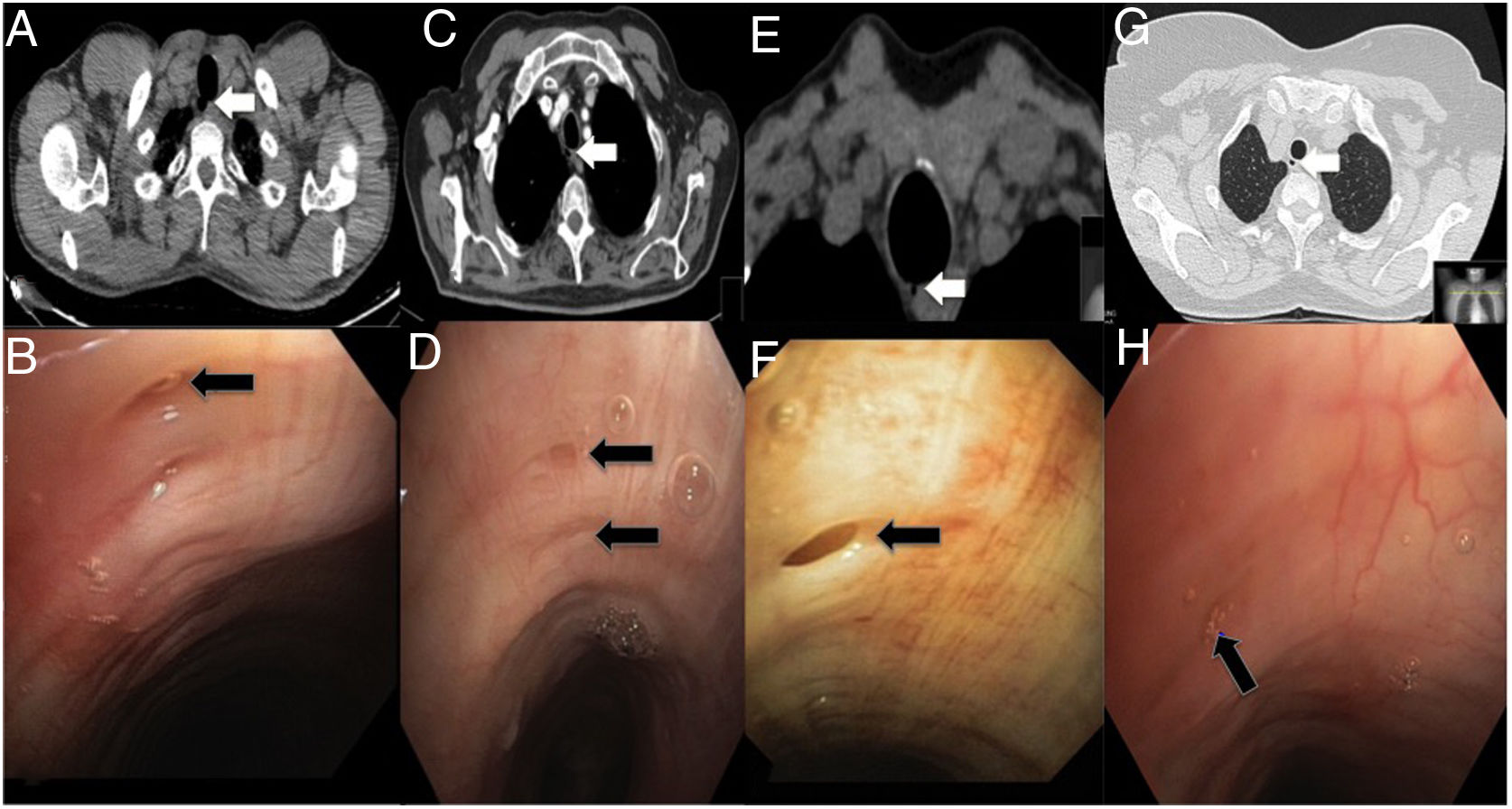

Tracheal diverticula (TD) are benign paratracheal air holes. TD are outpouchings composed of ciliated columnar epithelia connected to the tracheal lumen. They occur on the right posterolateral aspect of the trachea (97.1%) and can be congenital (developmental defects in tracheal cartilage) or acquired (increased intraluminal pressure).1 TD are generally an incidental finding in thoracic computed tomography examinations, as most patient remain asymptomatic. Therefore, the number of publications describing TD in connection with tracheal lumen and evidenced by fibrobronchoscopy (FBC) is limited. We report a case series of TD diagnosed in our center.

Case 1: A 40-year old, non-smoker patient referred for poor progression of respiratory infection. Pulmonary function tests were normal and thorax CT scan demonstrated a TD (Fig. 1A). FBC showed a TD opening in the right posterolateral aspect of the trachea, with a millimetric intraluminal connection (Fig. 1B).

Parts A, B, C and D contain chest CT scans for cases 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. White arrows indicate the tracheal diverticulum. Parts E, F, G and H show fibrobronchoscopy scans for cases 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. Black arrows indicate the connection of the tracheal diverticulum with the tracheal lumen.

Case 2: A 53 year-old never-smoker woman with a resected left breast infiltrating ductal carcinoma. The patient presented mMRC grade-2 dyspnea with obstructive spirometry and a positive bronchodilator test. Two TD were found incidentally on CT examination (Fig. 1C), which were confirmed by FBC [two TD on the right posterolateral wall of the trachea connected to the tracheal lumen (Fig. 1D)].

Case 3: An 82 year-old ex-smoker patient with suspected lung cancer whose thorax CT showed a TD (Fig. 1E). Spirometry was non-obstructive with a moderate diffusion defect. FBC confirmed the presence of a TD located on the right posterolateral aspect of the trachea connected to the trachea (Fig. 1F).

Case 4: A 72 year-old non-smoker woman who showed air bubbles in the right upper mediastinum consistent with TD (Fig. 1G). Only the upper diverticulum was seen to be connected to the trachea on FBC (Fig. 1H).

TD are outpouchings composed of ciliated-columnar epithelia generally connected to the tracheal lumen. They can be either single or multiple, their size ranging 1–30×5–25mm. They are located on the right posterolateral aspect of the trachea (T1–T3) probably due to the lack of adjacent structures supporting the trachea at that level. TD can be congenital or, more frequently, acquired. Congenital TD originate from defective tracheal cartilage and they contain respiratory epithelia, smooth muscle and cartilage (true diverticula).2 They are smaller, accumulate respiratory secretions and are narrow-mouthed. The usual location is on the right side, 4–5cm below the vocal cords or just above the main carina. Acquired TD arise from increased intraluminal pressure which leads to herniation of tracheal portions lacking cartilaginous rings. They are composed of ciliated-columnar epithelia without smooth muscle and cartilage (pseudo-diverticula).3 They are larger, broad-mouthed and can originate at any level (more frequently found on the posterolateral-aspect of the trachea).

The prevalence of TD in an autopsy series was 1%. Yet if CT examination is performed, prevalence increases to 2–8%.4 The vast majority of patients remain asymptomatic. Therefore, TD is generally found incidentally on thorax CT examination, which also shows the location, size and thickness of diverticular walls. FBC confirms TD connection to the lumen of the trachea, which may be challenging if connection is narrow or shows a fibrous tract. In published series, TD connection was only reported in 33.8–56.1% of patients.4 Symptomatic patients can show recurrent infections occassionally associated with hemoptysis, as it is the case of our patient 1. Orotracheal intubation can be challenging in these patients, and an association has been described with lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis [higher prevalence (18–28%) compared to other entities] or tracheobronchomegaly (Mounier–Kuhn's disease). In contrast, conclusive evidence has not been provided supporting an association with pulmonary emphysema.

Asymptomatic TD do not require any treatment. As to symptomatic TD, there is no solid evidence supporting a specific therapeutic approach, as age, comorbidities and symptoms must be considered.5 Therapeutic options include the management of clinical symptoms (mucolitics, antibiotics, physiotherapy), open surgical resection by transcervical approach, or laser endoscopy or electrocoagulation.6 Early diagnosis of symptomatic TD is crucial to prevent the development of infection, as untreated symptomatic TD generally have a poorer prognosis. Some patients have been reported to develop respiratory distress requiring emergency orotracheal intubation or paratracheal abscesses requiring surgical drainage.7 The laryngeal nerve or the esophagus can be damaged as a result of surgery; therefore, surgery should be reserved for very specific cases.

In summary, TD are outpouchings most frequently found on the right posterolateral aspect of the trachea and are subdivided into congenital or acquired. The number of case reports describing TD connection with the tracheal lumen as seen by FBC is limited. Although patients usually are asymptomatic and will not require treatment, fair recognition of these lesions can contribute to the management of its rare complications.