The use of monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based therapies is becoming the new standard of care for severe uncontrolled asthma (SUA). Even though patients may qualify for one or more of these targeted treatments, based on different clinical criteria, a global vision of mAb prescription management in a large sample of hospitals is not well characterised in Spain.

The objective was to give a global vision of mAb prescription management in a large sample of hospitals in Spain.

Materials and methodsWe used an aggregate data survey method to interview pulmonology specialists in a large sample of Spanish centres (90). The following treatment-related information was obtained on patients treated with mAbs: specific mAbs prescribed, treatment interruption, switch and restart and the reasons for these treatment changes.

ResultsmAb prescription was more frequent in females (13.3% females vs 7.4% males; p<0.001). There were no differences in prevalence by hospital complexity level. In contrast, there were differences by geographical area. Omalizumab was the most prescribed mAb (6.2%), followed by mepolizumab (2.9%). Discontinuation of Omalizumab (due to a lack of effectivity) and switches from this mAb to mepolizumab were more frequent. Very few restarts to the first treatment were observed after a switch from ≥2mAbs.

ConclusionsOmalizumab appeared as the most prescribed mAb in SUA but was also the most withdrawn; a specific and objective characterisation of patients with SUA, along with asthma phenotyping, and together with further evaluation of safety and effectiveness profiles, will lead to future progress in the management of SUA with mAbs.

El uso de terapias basadas en anticuerpos monoclonales (mAb) se está convirtiendo en el nuevo estándar de atención para el asma grave no controlada (AGNC). A pesar de que los pacientes pueden optar a uno o varios de estos tratamientos dirigidos, con base en diferentes criterios clínicos, en España no se ha caracterizado bien una visión global de la gestión de la prescripción de mAb en una gran muestra de hospitales.

El objetivo fue dar una visión global de la gestión de la prescripción de mAB en una amplia muestra de hospitales en España.

Materiales y métodosSe utilizó un método basado en una encuesta de datos agregados para entrevistar a especialistas en Neumología en una amplia muestra de centros españoles (90). Se obtuvo la siguiente información relacionada con el tratamiento de los casos tratados con mAbs: mAbs específicos prescritos, interrupción del tratamiento, cambio y reinicio, y las razones de estos cambios de tratamiento en consultas de Neumología.

ResultadosLa prescripción de mAB fue más frecuente en mujeres (13,3% mujeres vs. 7,4% hombres; p<0,001). No hubo diferencias de prevalencia por nivel hospitalario. En cambio, hubo diferencias por área geográfica. Omalizumab fue el mAb más prescrito (6,2%), seguido de mepolizumab (2,9%). La interrupción y los cambios (debido a la falta de efectividad) también fueron más frecuentes para omalizumab.

ConclusionesOmalizumab fue el mAb más prescrito en el manejo de AGNC, pero también fue el mAB que presentó más retiradas; una caracterización específica y objetiva de los pacientes con AGNC, mediante fenotipificación de asma, junto con una evaluación adicional de los perfiles de seguridad y efectividad, conducirá a nuevos avances en el manejo del AGNC con mABs.

Monoclonal antibody (mAbs) treatments have important therapeutic applications in different diseases. Currently, a number of biological drugs are available that have proven to be quite effective and efficient in reducing exacerbations1 and improving quality of life2 in adults and children with moderate to severe asthma (SA).3–5 In this sense, severe uncontrolled asthma (SUA) is as an important challenge not only for health professionals but also for patients who suffer from it.6

Different mAbs have emerged to treat different types of SUA. Specifically, there are four biologic mAbs approved for clinical use. These are Omalizumab for allergic asthmatic patients (anti-IgE)7–9 and three others targeting eosinophilic inflammation (mepolizumab,10,11 reslizumab, and benralizumab,12–14,3,15 all which show very positive results.

Among these, Omalizumab was the first mAb approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003,16 and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2005.17 In the last five years three new mAbs have emerged for use in eosinophilic SUA. Much of the literature cites both the benefits and drawbacks of using these drugs in SUA. However, given the complexity of asthma and its management, the presence of SUA, and specifically, to what extent these mAbs are or are not prescribed and why is not fully understood.

Different health professionals have been involved in controlling the disease depending on where the patients seek help, i.e. general practitioners or specialists. However, in some cases there is not always an accurate diagnosis of asthma, thus leading to the inadequate management of SA.18 Due to this, the mAbs prescription that comes from the different health consultations is not well characterised. That is, in the field of pulmonology, due to the complex and very heterogeneous inflammatory nature of respiratory processes, the use of these treatments has been delayed despite a high prevalence of SUA cases in this specialty. Furthermore, given that sex has been reported to play a key role in asthma,19 assessing how these mAbs treatment patterns may differ between males and females is of particular interest.

Given the gap in knowledge regarding the mAbs prescription in Spain, in this study we aimed to characterise the management pattern of mAbs in a large sample of patients with SUA treated by Spanish pulmonologists. Complementary to this, we also assessed the prevalence of mAbs prescriptions by sex and specialty.

Material and methodsThe current study belongs to a broader project where the objective is to describe a global map of mAbs prescription for SUA in Spain, as well as the characteristics of such prescriptions.20 In the present study, we evaluate the mAbs prescriptions’ patterns, by sex, by hospital complexity level, by geographical area, type of mAb, as well as treatment interruptions, switches and restarts.

Participants and data collectionThe study is based on a survey of aggregated data, collected from hospital pharmacy lists of patients with SUA who are currently or have been treated with mAbs in the last 5 years. Data were analysed in centres from the National Health System (NHS) hospital catalogue, in Spain, available on the website of the Ministry of Health for 2018.21

The inclusion criteria of the selected centres included: belonging to the NHS in any region, having a pulmonology department and a hospital pharmacy, as well as data on the prescription of mAbs in patients with SUA from the last 5 years. All private and public hospitals without these characteristics were excluded.

Pulmonology specialists who agreed to participate in the study completed an electronic survey from 1 July to 4 November 2019.

A proportional randomised sampling of centres was carried out, stratifying by five geographical areas of Spain (north, south, east, Canary Islands and central zone)20 and four hospital complexity levels (according to the number of beds: level 1, ≤250; level 2, 251–500; level 3, 501–800; level 4, >800 beds), based on a finite population of 189 hospitals that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, which was adopted as a sampling basis.

Using this sample and considering the finite population sampling correction factor, to estimate an unknown proportion (assuming a case weighting of 50%) with a 95% confidence interval and with an estimation error of ±5%, data from 112 hospitals were needed. To prevent a 20% loss of information, 140 hospitals had to be recruited. Investigators from 140 hospitals of the pulmonology departments were contacted and 100 principal investigators agreed to participate. Centres that provided the necessary information to assess the total number of patients currently treated with mAbs and the size of the centre's reference population were considered valid.

Variables collectedVariables related to the stratified study design, the demographic characteristics of patients with mAbs, and the mAb prescription were collected, which included hospital complexity levels (see above), sex of patients, prevalence and number of cases treated with mAbs, type of mAb prescribed (omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab), and time (current and since the introduction of the use of mAbs). It also included treatment interruption, switch and restart and reasons for treatment changes. The prescription of mAbs was stratified according to sex and time.

Statistical analysisThe SUA prevalence was calculated by multiplying the reference population of each site by the percentage of adults in the Spanish population (84.2%),22 the estimated prevalence of asthma in an adult population (5%),23 and the proportion of asthma patients with SUA (3.9%).1 The prevalence of treatment with mAbs in patients with SUA was calculated by dividing the number of patients currently treated with any mAbs by the estimated number of patients with SUA.

Medians and quartiles (Q1, Q3), and absolute and relative frequencies were used to describe quantitative and categorical variables, respectively. Comparisons of population treated with mAb by groups (sex, hospital complexity level, geographical area) were performed by means of the Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Prevalence estimates of current treatment with mAb and comparisons by sex, hospital complexity level and geographical area were performed taking into account the survey design using the survey package24 of the R statistical software version 4.2.0, 2022.

EthicsThis work has been carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 1983 and all the pulmonologists were informed about the study and signed an informed consent.

ResultsA total of 91 centres were initially included. One of them was discarded because there was missing information regarding the objective of the study. The classification of the 90 final participant centres by the capacity of the hospital was: level 1 n=20 (22.2%), level 2 n=30 (33.4%), level 3 n=19 (21.1%) and level 4 n=21 (23.3%). 100% of pulmonology specialists prescribed mAb for SUA.

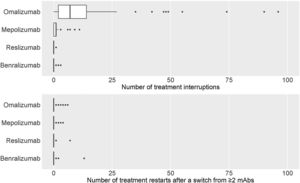

Prevalence of mAb treatments by sexGlobal current mean prevalence (95% confidence interval [CI]) of cases treated with mAbs was 10.4% (8.8–12.1%). There was a significant difference in the prevalence of current mAb treatment by sex (p<0.001) (Fig. 1a) with females showing a higher prevalence: 13.3% (11.1–15.5%) in females and 7.4% (6.3–8.6%) in males. The distribution by sex of the total number of patients treated with mAbs since their use was established in each centre and it showed the same trend (p<0.001): median (Q1, Q3) in females 23 (12, 37.8); and in males 11 (6.2, 18.8) (Fig. 1b).

Prevalence and number of patients with mAb prescription by sex. (a) Prevalence of patients with mAb prescription by sex. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients with mAb prescription by sex. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).

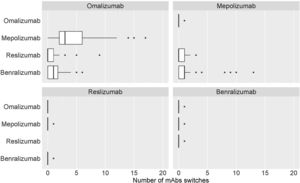

By hospital complexity level, the prevalence was 8.8% (6.9–10.6%) in level 1, 11.7% (7.1–16.3%) in level 2, 11.7% (9.6–13.8%) in level 3 and 9.4% (8.3–10.5%) in level 4; no statistically significant differences were observed (p=0.597) (Fig. 2).

Prevalence and number of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. (a) Prevalence of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).

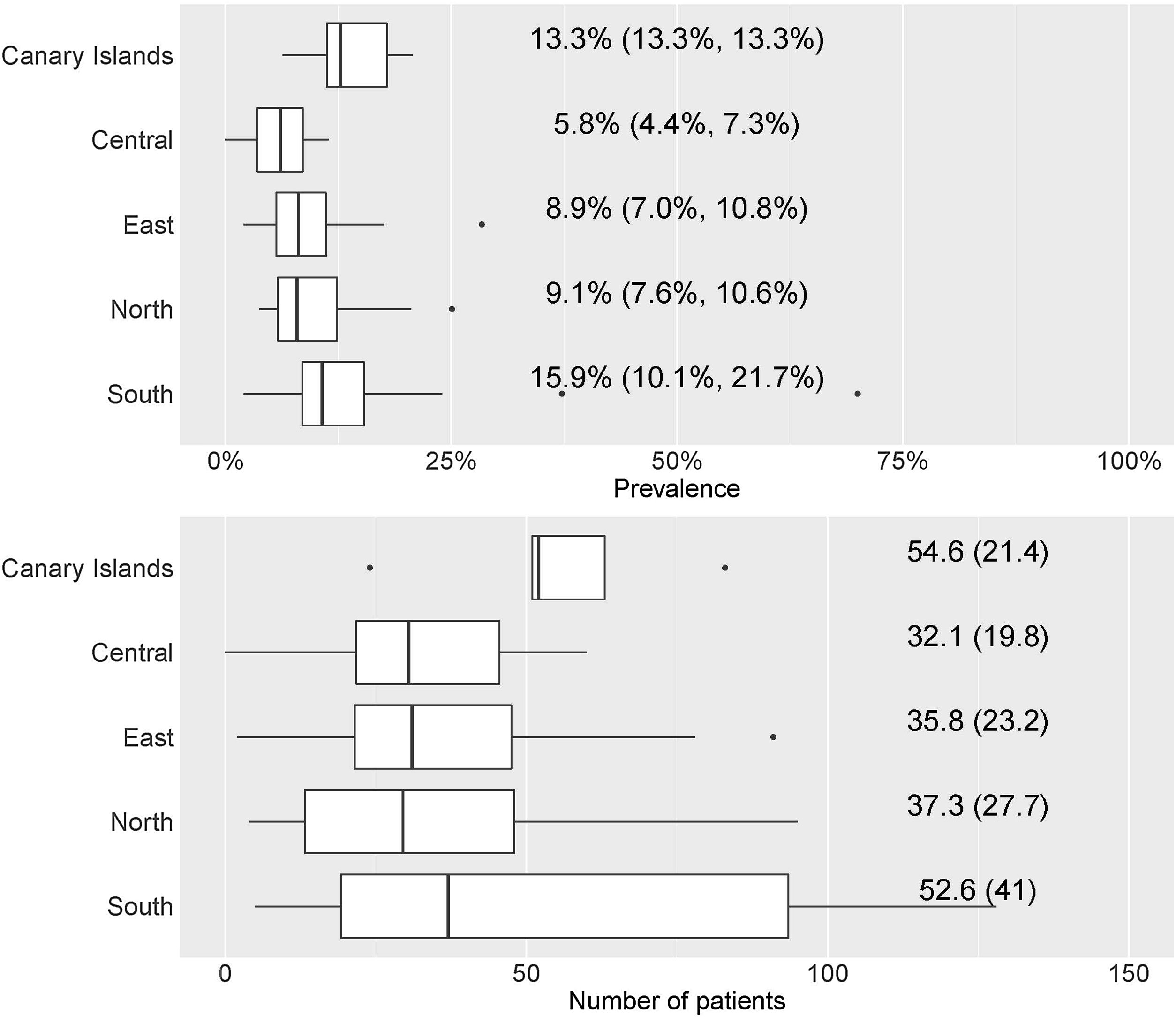

By geographical area, the prevalence was 13.3% (13.3–13.3%) in the Canary Islands, 5.8% (4.4–7.3%) in the central area, 8.9% (7.0–10.8%) in the eastern area, 9.1% (7.6–10.6%) in the northern area, and 15.9% (10.1–21.7%) in the southern area; statistically significant differences were observed (p=0.01) (Fig. 3).

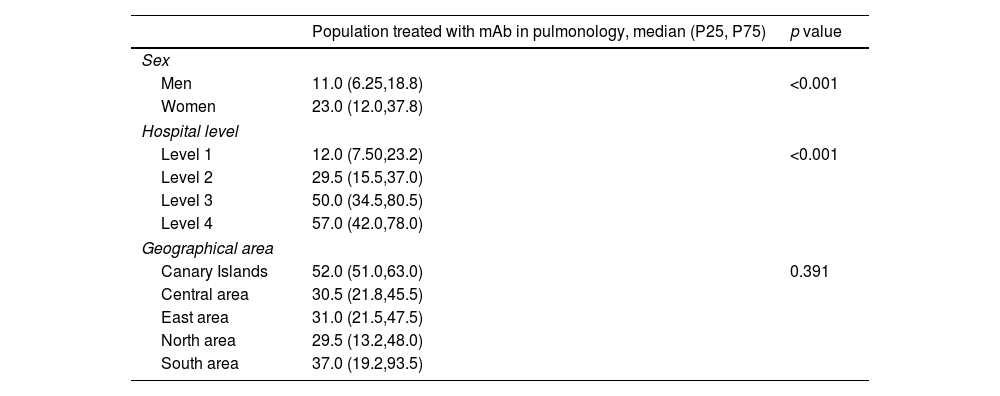

Table 1 shows the descriptive results of the population treated by sex, hospital complexity level, and geographic area.

Population treated by sex, hospital level and geographical area.

| Population treated with mAb in pulmonology, median (P25, P75) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 11.0 (6.25,18.8) | <0.001 |

| Women | 23.0 (12.0,37.8) | |

| Hospital level | ||

| Level 1 | 12.0 (7.50,23.2) | <0.001 |

| Level 2 | 29.5 (15.5,37.0) | |

| Level 3 | 50.0 (34.5,80.5) | |

| Level 4 | 57.0 (42.0,78.0) | |

| Geographical area | ||

| Canary Islands | 52.0 (51.0,63.0) | 0.391 |

| Central area | 30.5 (21.8,45.5) | |

| East area | 31.0 (21.5,47.5) | |

| North area | 29.5 (13.2,48.0) | |

| South area | 37.0 (19.2,93.5) | |

mAb: monoclonal antibodies; P25, P75, percentile 25 and 75.

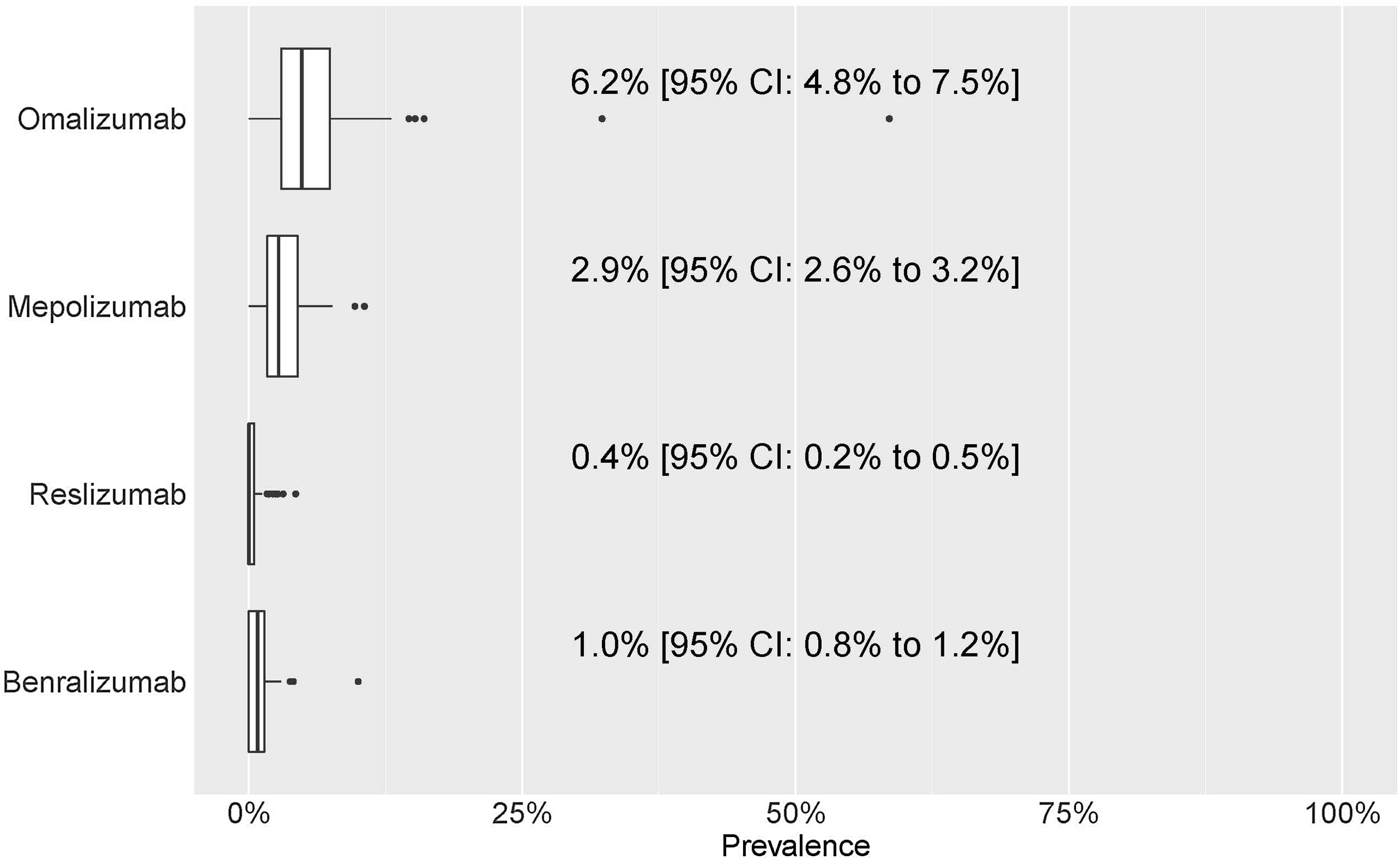

For each of the four mAbs, the prevalence of treatment by pulmonology services was: omalizumab, 6.2% (4.8–7.5%); mepolizumab, 2.9% (2.6–3.2%); reslizumab, 0.4% (0.2–0.5%); and benralizumab, 1.0% (0.8–1.2%) (Fig. 4). eTable1 shows the results of the prevalence of treatment by sex, hospital complexity level, and geographic area. The descriptive results of the population treated with each of the mAbs by sex, hospital complexity level and geographic area shown in eTable 2 of eSupplement Material.

Prevalence of treatment. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). Patients’ distribution attending different mAb prescriptions (a) since mAb prescription was established in each centre and (b) patients who discontinued the mAb treatment and do not continue with other mAb. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).

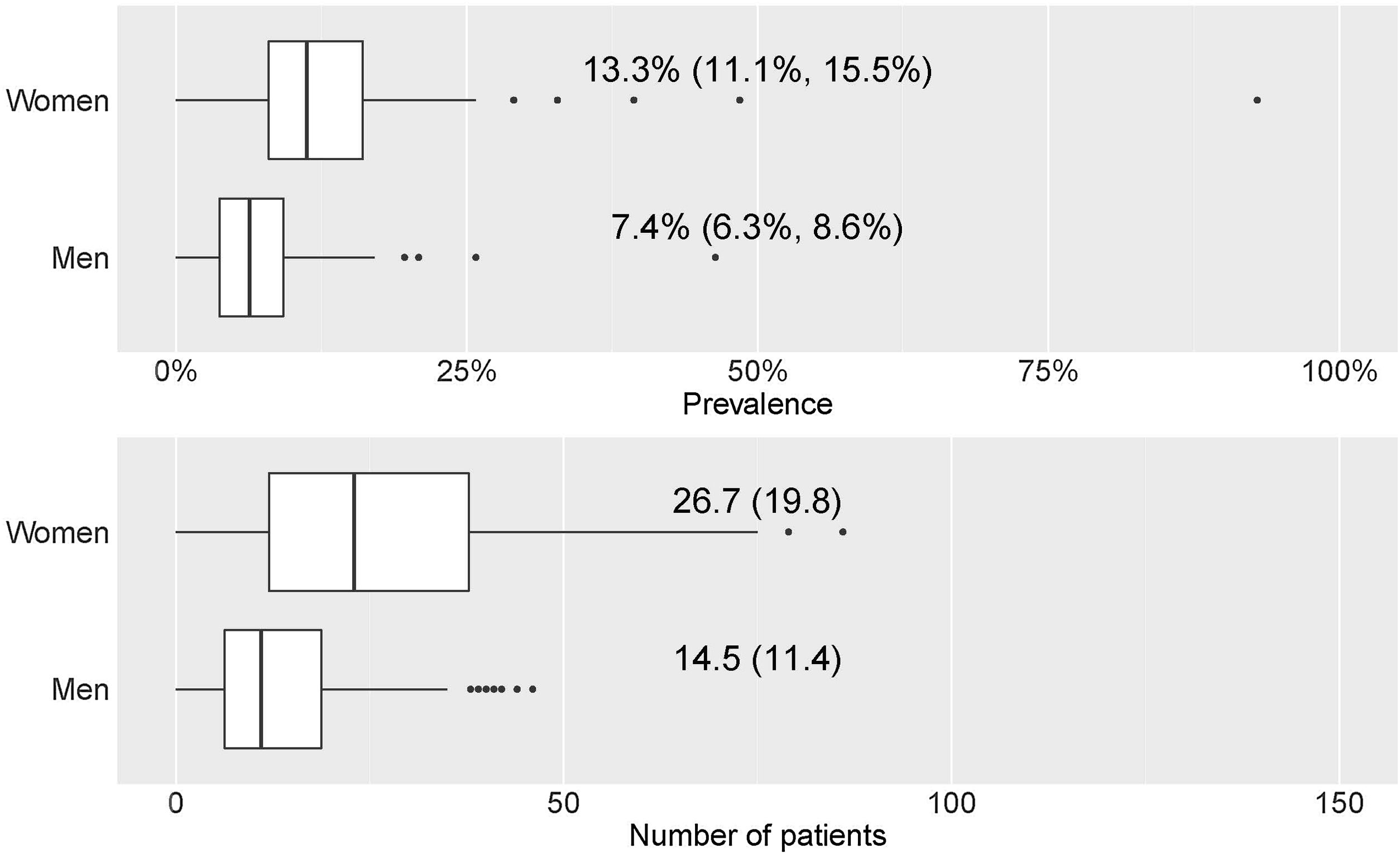

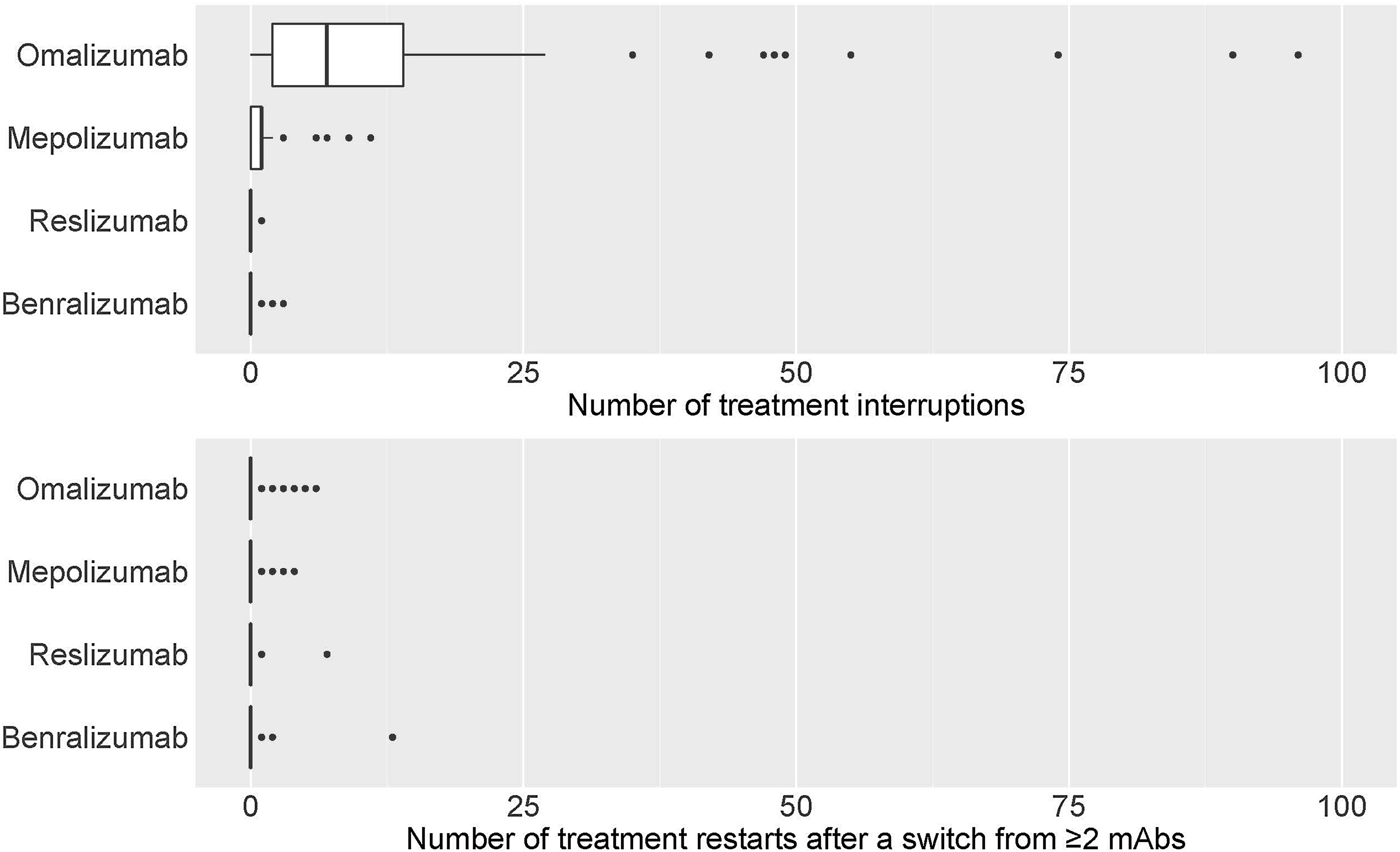

eTable3 shows the total number of treatment interruptions of mAbs, along with the reasons for all centres. Discontinuations were higher for omalizumab, followed by mepolizumab. The main reason for discontinuation was a lack of effectivity (Fig. 5a).

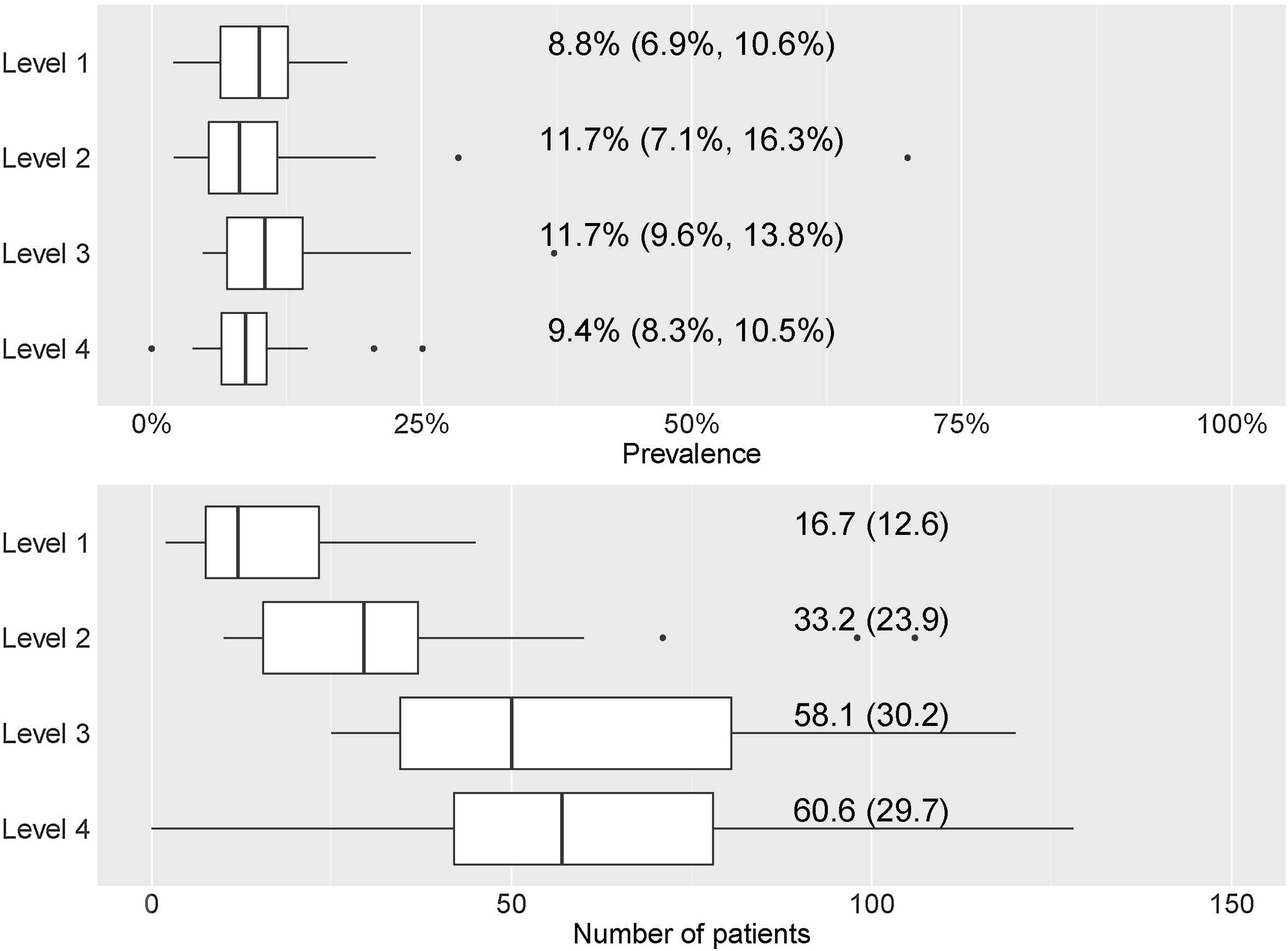

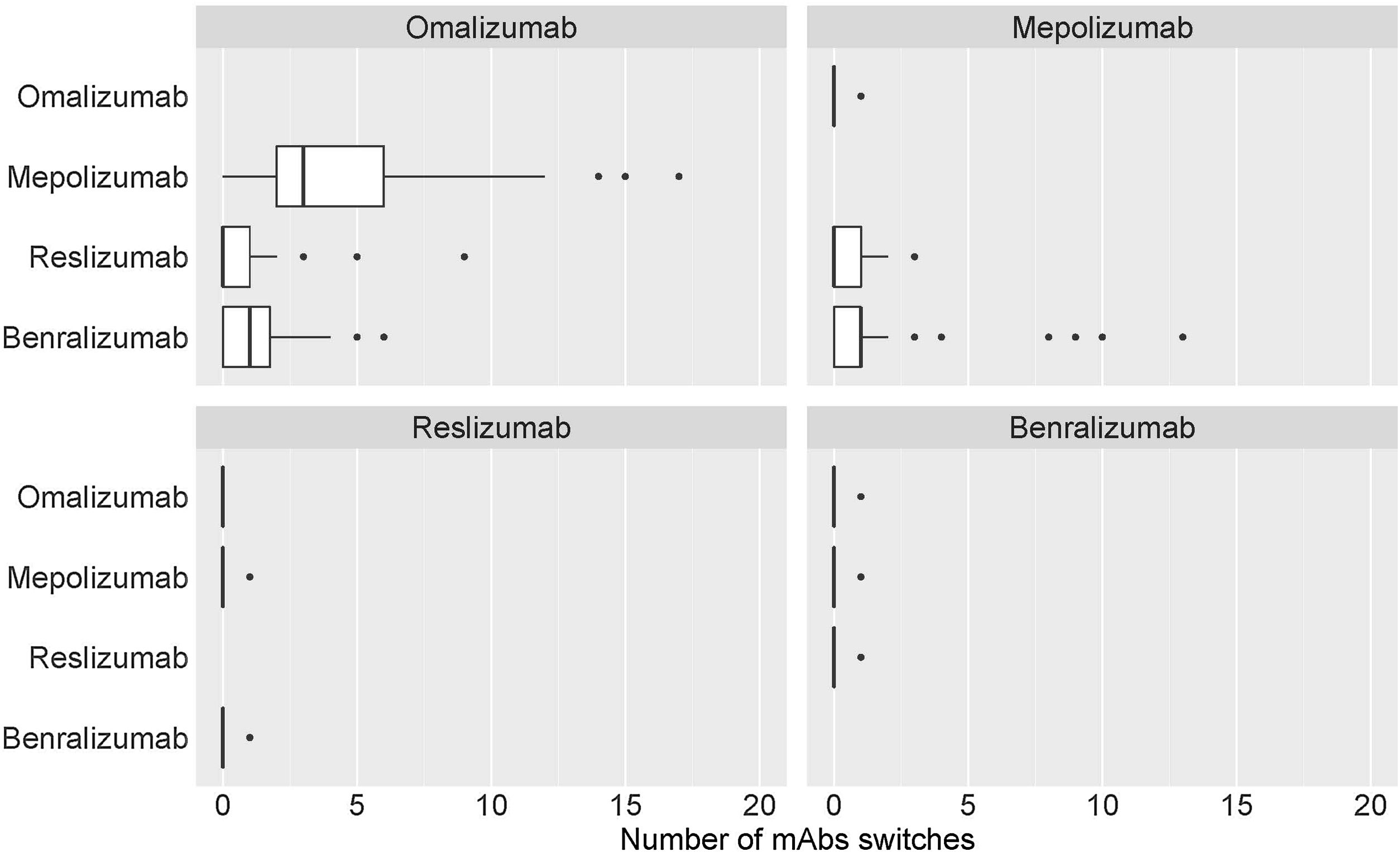

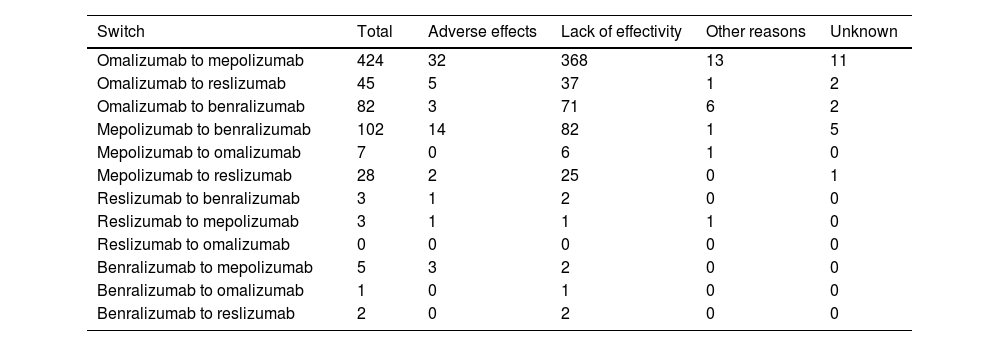

Table 2 shows the distribution of the total number of patients who have had their prescribed mAbs switched, with omalizumab showing the highest number of switches, especially to mepolizumab. Again, the main reason for switching was a lack of effectiveness of treatment. The second mAb showing more switches was mepolizumab to benralizumab (Fig. 6).

mAbs switches and reasons.

| Switch | Total | Adverse effects | Lack of effectivity | Other reasons | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omalizumab to mepolizumab | 424 | 32 | 368 | 13 | 11 |

| Omalizumab to reslizumab | 45 | 5 | 37 | 1 | 2 |

| Omalizumab to benralizumab | 82 | 3 | 71 | 6 | 2 |

| Mepolizumab to benralizumab | 102 | 14 | 82 | 1 | 5 |

| Mepolizumab to omalizumab | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Mepolizumab to reslizumab | 28 | 2 | 25 | 0 | 1 |

| Reslizumab to benralizumab | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Reslizumab to mepolizumab | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Reslizumab to omalizumab | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Benralizumab to mepolizumab | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Benralizumab to omalizumab | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Benralizumab to reslizumab | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

mAb: monoclonal antibodies.

eTable4 shows the distribution of the total number of patients where the first prescribed mAb was restarted after a switch from ≥2mAbs. There were a few restarts to the first treatment that, in most cases, was omalizumab, followed by benralizumab and mepolizumab. The lack of effectiveness appeared as the main reason for restarting the first mAb treatment (Fig. 5b).

DiscussionWhen this study was first constructed and designed, it was the first study to describe the pattern and type of mAb prescription in SUA. It was implemented in a large sample of public health centres with a pulmonology service, taking into account sex, hospital complexity level and geographical area. In January 2022, an international registry that describes real-life global patterns of biologic use (continuation, switches, and discontinuations) for severe asthma was published.25 In our study, notably, a sex difference was found, with females showing a higher prevalence of mAbs being prescribed. As in the international registry,25 Omalizumab was the most prescribed mAb, as it has been available for a longer period of time, followed by mepolizumab. However Omalizumab also showed the highest levels of treatment discontinuation. The main switches were from omalizumab to mepolizumab, and from mepolizumab to benralizumab. These results are similar to those published in the international registry.25 There were few restarts to the first treatment (after a change of ≥2mAbs) which in most cases was omalizumab. Lack of effectivity was the main reason for treatment discontinuation and switches.

Patients with SUA are eligible for mAb treatments, depending on different clinical and medical criteria. However, there is a lack of characterisation of mAb prescription mapping, especially in some European countries. Routine options for treating asthma remain limited and there are very few studies on the proportion of patients eligible for mAb. We found that 10.4% of patients with SUA were treated with mAbs. In a population with SA from a Canadian allergist's practice, between 41% and 78% of patients (depending on the mAb) were eligible for at least one mAb.26 Our data are fall below these eligibility percentages. A study conducted in Spain on a sample of 303 patients with SA (67% women) shows that mAb are not usually prescribed during the severe exacerbation phases, but only during the stable phase in 39% of cases.27

Consistent with previous studies,27,28 mAb treatments were prescribed significantly more in females. Sex plays an important role in asthma, from males having the highest prevalence in childhood to females in adulthood.19 A new hypothesis related to SA pathophysiology phenotypes involves asthma with non-eosinophilic inflammation, obesity and occurrence only in females.29 In this regard, future studies on mAb prescription should take into account the type of SA. Therefore, there is a need to better characterise and phenotype patients with SA before requesting mAb treatment, also taking into account the phases (stable or exacerbations) in which patients seek healthcare help.30 Studies on the impact of sex on treatment effectiveness are unclear, with some studies indicating that sex does not predict response to mAbs.31,32

Omalizumab was the most prescribed mAb, followed by mepolizumab. Omalizumab was the first mAb approved for allergic SA.33 There is variability in the published data on the percentage of patients with allergic and eosinophilic asthma. Allergic asthma is demonstrable in a variable proportion of patients (11–60% of cases) while the eosinophilic phenotype accounts for about 25–58% of the cases,34,35 the idiosyncrasies of patients in the centres evaluated may contribute to these results.

Interestingly, since patients with SA may present with an overlap of eosinophilic and allergic phenotypes, both omalizumab and mepolizumab, primarily, are commonly discussed as the best treatment for these cases.36 In this regard, both mAbs have shown similar efficacy in patients with SUA.37 Previous literature shows that the high heterogeneity of cases and the different selection criteria for the use of the two mAbs probably do not allow for a specific and concrete criterion for using one or the other mAb, also taking into account that they have similar efficacy patterns.37

The prevalence of treatment discontinuation was also more reported for these two mAbs. Omalizumab withdrawal rates have been shown to vary considerably depending on the type of study, ranging from 2% to 19% in double-blind and open-label studies.38

In SUA cases, switching between mAbs can occur.39 Most switches were observed from omalizumab (about 78%, 551 out of 702) to mepolizumab (60%), and from mepolizumab to benralizumab (14%). There is a clear effect of sample size treated with omalizumab that makes treatment discontinuation more evident for this mAb. This could be because it was the monoclonal available for most of the study period. It could also be possible that more failures could have been seen with other mAbs if the study had lasted longer. In addition, despite omalizumab being considered the gold standard treatment in severe allergic asthma, it is possible that incorrect asthma phenotype selection has occurred, leading to a negative clinical outcome.40 Some studies suggest that switching from omalizumab to mepolizumab in patients with uncontrolled severe allergic and eosinophilic asthma may lead to clinically significant improvements in asthma control.40,41 The literature is not sufficiently clear on which mAb (mepolizumab or benralizumab) is the best for treating eosinophil SA. On one hand, studies highlight similar efficacy42; however on the other hand, some studies attribute unique characteristics to benralizumab in inhibiting the mechanism of eosinophil depletion and maturation in the bone marrow, thus inducing cell-mediated, antibody-dependent cytotoxicity in both circulating and tissue-resident eosinophils43–45 that have not been attributed to other mAbs (i.e. mepolizumab). Benralizumab is therefore postulated as an alternative to other agents targeting the IL-5 pathway in the treatment of eosinophilic asthma.44

There were few restarts of the first treatment after a switch from ≥2mAbs, and, in the few cases, it was to omalizumab. We found that the rates of withdrawal or switches from omalizumab, as well as the other mAbs, have been associated with a lack of efficacy, in agreement with previous studies.46,47 The question here is: where do these severe cases that do not respond to even two treatment switches stand? It seems difficult to find an alternative in severe cases that maximises disease control.

This study is not without limitations. The nature of the survey method has several inherent advantages, but also weaknesses. For example, there were centres that were difficult to access, as we could not survey the initially calculated sample size. The reliability of the survey also depends on different factors, such as errors in the data due to non-response, or differences in the number of respondents (in this case, centres) who chose to participate from those who chose not to, which creates bias.

In conclusion, we found differences in overall mAb prescribing according to sex, specialty and hospital complexity level. Omalizumab appeared as the most prescribed mAb, but also with higher rates of treatment discontinuation, mainly due to lack of effectiveness. Proper knowledge and management of the disease as well as its associated comorbidities are essential for the successful management of the disease in the future, as there are still high drop-out rates.

FundingFunding obtained from the Asthma Area of the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery.

Authors’ contributionsAll the authors of this document made substantial contributions to conception and design. FC contributed to draft it and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflicts of interestFrancisco Casas-Maldonado declares that he has received fees in the last three years for acting as a speaker from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Laboratorios Esteve, Laboratorios Ferrer, Menarini, Novartis, Rovi, TEVA, VERTEX, and Zambon; he has also received grants for conference attendance from Boehringer Ingelheim, Grifols, Menarini, and Novartis; finally, he has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, and Grifols. Marina Blanco Aparicio declares that in the last three years she has received fees for participating as a speaker at meetings sponsored by Astrazeneca, Novartis, TEVA, and GSK and as a consultant for AstraZeneca, GSK, Chiesi, Novartis, and Bial. She also received financial aid to attend congresses. Francisco-Javier González-Barcala declares that in the last three years he has received grants for attending congresses, lectures or research grants from ALK, Astra-Zeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Laboratorios Esteve, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Rovi, Roxall, Stallergenes-Greer, and Teva. Christian Domingo Ribas declares having received in the last three years collaborations for travel and participation in congresses, conferences or scientific meetings from Novartis, Sanofi, GSK, TEVA, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Esteve, Almirall, Astra-Zeneca, Chiesi, Menarini, Takeda, Pfizer, Ferrer, Stallergenes, ALK-Abelló, Allergy therapeutics, Hall Allergy, Inmunotek, and Roxall. Carolina Cisneros Serrano declares having received fees in the last three years for acting as a speaker from Astrazeneca, GSK, TEVA, Menarini, Mundipharma, and Novartis; she received grants for attending congresses from Chiesi, TEVA, Menarini, and Mundipharma; and she has also received fees for acting as a consultant from ALK, Astrazeneca, MundiPharma, TEVA, GSK, and Novartis. Gregorio Soto Campos reported having received fees in the last three years for acting as a speaker for Astrazeneca, Boehringer and Novartis and as a consultant for AstraZeneca, GSK, Chiesi, Novartis, and Bial. He also received financial aid for attending congresses from Boehringer, Menarini, and Novartis and received grants for research projects from Novartis, GSK and Boehringer. Berta Román Bernal in the last three years reports having received honoraria for participating as a speaker from Astrazeneca, Teva, Novartis, and GSK. She has also received grants for attending congresses and courses from Astrazeneca, Teva, Novartis, Menarini, and GSK. Francisco-Javier González-Barcala declares that in the last three years he has received grants for attending congresses, lectures or research grants from ALK, Astra-Zeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Laboratorios Esteve, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Rovi, Roxall, Stallergenes-Greer, and Teva.

We would like to thank all the researchers from the different hospitals that have participated in this study for their efforts in collecting the data, and all those responsible for the hospital pharmacy services for the facilities they have given us to obtain the lists of treatments with mAbs for severe bronchial asthma.

![Prevalence and number of patients with mAb prescription by sex. (a) Prevalence of patients with mAb prescription by sex. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients with mAb prescription by sex. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation). Prevalence and number of patients with mAb prescription by sex. (a) Prevalence of patients with mAb prescription by sex. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients with mAb prescription by sex. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/26596636/0000000500000003/v2_202312041346/S2659663623000218/v2_202312041346/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Prevalence and number of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. (a) Prevalence of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation). Prevalence and number of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. (a) Prevalence of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients treated with mAb by hospital level. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/26596636/0000000500000003/v2_202312041346/S2659663623000218/v2_202312041346/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![(a) Prevalence and number of patients treated with mAb by geographical area. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients treated with mAb by geographical area. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation). (a) Prevalence and number of patients treated with mAb by geographical area. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). (b) Number of patients treated with mAb by geographical area. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/26596636/0000000500000003/v2_202312041346/S2659663623000218/v2_202312041346/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Prevalence of treatment. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). Patients’ distribution attending different mAb prescriptions (a) since mAb prescription was established in each centre and (b) patients who discontinued the mAb treatment and do not continue with other mAb. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation). Prevalence of treatment. Numerical data indicate the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]). Patients’ distribution attending different mAb prescriptions (a) since mAb prescription was established in each centre and (b) patients who discontinued the mAb treatment and do not continue with other mAb. Numerical data indicate mean (standard deviation).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/26596636/0000000500000003/v2_202312041346/S2659663623000218/v2_202312041346/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)