Studies have examined the relationship between positive and negative emotions with self-efficacy, but we consider that some theoretical and methodological aspects are missing. In this study, the difficulties in participants’ emotional regulation were included as a co-variable. We analyzed factors undergoing the absence of affective congruity. An experimental design taking the type of induced emotions (positive vs. negative) as independent variable was carried out. The manipulation of this variable was effected with the combined exhibition of movie/music. The results suggest that the induction of positive and negative mood states increases and decreases respectively, the levels of self-efficacy. This was only observed in participants in a condition of intense or raised mood and in atypical or slightly accurate items of character. We concluded that the induction of positive and negative mood states increases and decreases respectively the levels of academic self-efficacy in college students and that the difficulty in the emotional regulation modulates the effect of inductions of mood states.

Numerosos estudios han examinado la relación entre emociones positivas y negativas y autoeficacia, aunque consideramos que algunos aspectos teóricos y metodológicos no son contemplados. En este estudio se icluyen como covariables las dificultades en la regulación emocional de los participantes. Así, analizamos algunos factores que pueden producir la ausencia de congruencia afectiva. Se llevó a cabo un diseño experimental que considera como una variable independiente el tipo de emoción inducida (positiva vs negativa). La manipulación de esta variable se efectuó a través de la exposición combinada de película/música. Los resultados sugieren que la inducción de estados de ánimo positivos y negativos aumentan y disminuyen, respectivamente, los niveles de autoeficacia. Esto solo fue observado en participantes que demostraron una condición de ánimo intenso o aumentado y en aquellos ítems atípicos o poco seguros. Concluimos que la inducción de estados de ánimo positivos y negativos aumenta y disminuye, respectivamente, los niveles de autoeficacia académica en estudiantes universitarios. La dificultad en la regulación emocional modula el efecto de la inducción del estado de ánimo.

There is evidence about the consequences of affects on cognition, and diverse theories, with a degree of complementarity, have developed in order to explain the relation between affects and cognition (Forgas, 2001). One of these pieces of evidence is the Informational Affect Theory (e.g., Affect Infusion Model; Affect-as-Information Model), explaining that affect can notify the content of thoughts, judgments, and decisions of people (Forgas, 2001). Likewise, other lines of research were aimed at demonstrating that the affect is an essential component for the achievement of a cognitive adaptive response (Adolphs & Damasio, 2001). In sum, it is possible to affirm that affect is an essential factor of cognitive processes and that affect modulates the information processing in multiple domains.

Special attention deserves the analysis of the relation between emotions and judgments of self-efficacy. This variable modulates the choice of activities and behaviors; the patterns of thoughts determine the effort and the perseverance that the person devotes, and finally it lets organize and execute the necessary action courses to reach a good performance (Bandura, 1997).

Bandura (1997) postulated that the mood state could influence the self-efficacy judgments in two ways, direct and indirect. A person's affective state could influence directly the self-efficacy because the emotional state could operate as a sign or information to judge the own capacities. In relation to the Affect-as-Information Model (Schwarz & Clore, 1983), people use their affective states to produce a quick judgment without trying to integrate the external characteristics with their own memory and the internal associations to generate a judgment. However, for Bandura (1997), the impact of this pathway should not be so important, because it depends on the way this information is interpreted.

The major influence of the emotional state on judgments of self-efficacy is an indirect one. Bandura (1997) explains that memory provides the necessary information to make judgments of self-efficacy. The emotional state activates articulated memories with the affect, facilitating the recall of successful experiences (when the emotional state is positive) or failure (when the emotional state is negative), consistently affecting the judgments of personal efficiency.

The idea that the intensity of the emotional states reaches to distort the attention and influences the way in which people interpret and recover information can be deduced from the Associative Network Theory proposed by Bower and Forgas (2003). According to this model, there are emotional nodules connected in the brain, and each one has multiple situational detectors. When an emotion is activated in an evocative situation, this emotional nodule extends the excitation to a series of indicators which are connected. The indicators include physiological reactions, facial expressions, action trends, and memories of events that have been associated with past emotions. As a result, when an emotion is activated, the concepts, words, topics, and rules of inference that are associated with each emotion are primed and more available for its use. In line with this, the emotional state will put in the first line some perceptual categories, topics, and manners of interpretation that are coherent with the emotional state. These “mental samples” will act as interpretative filters of reality, introducing a bias in the judgments.

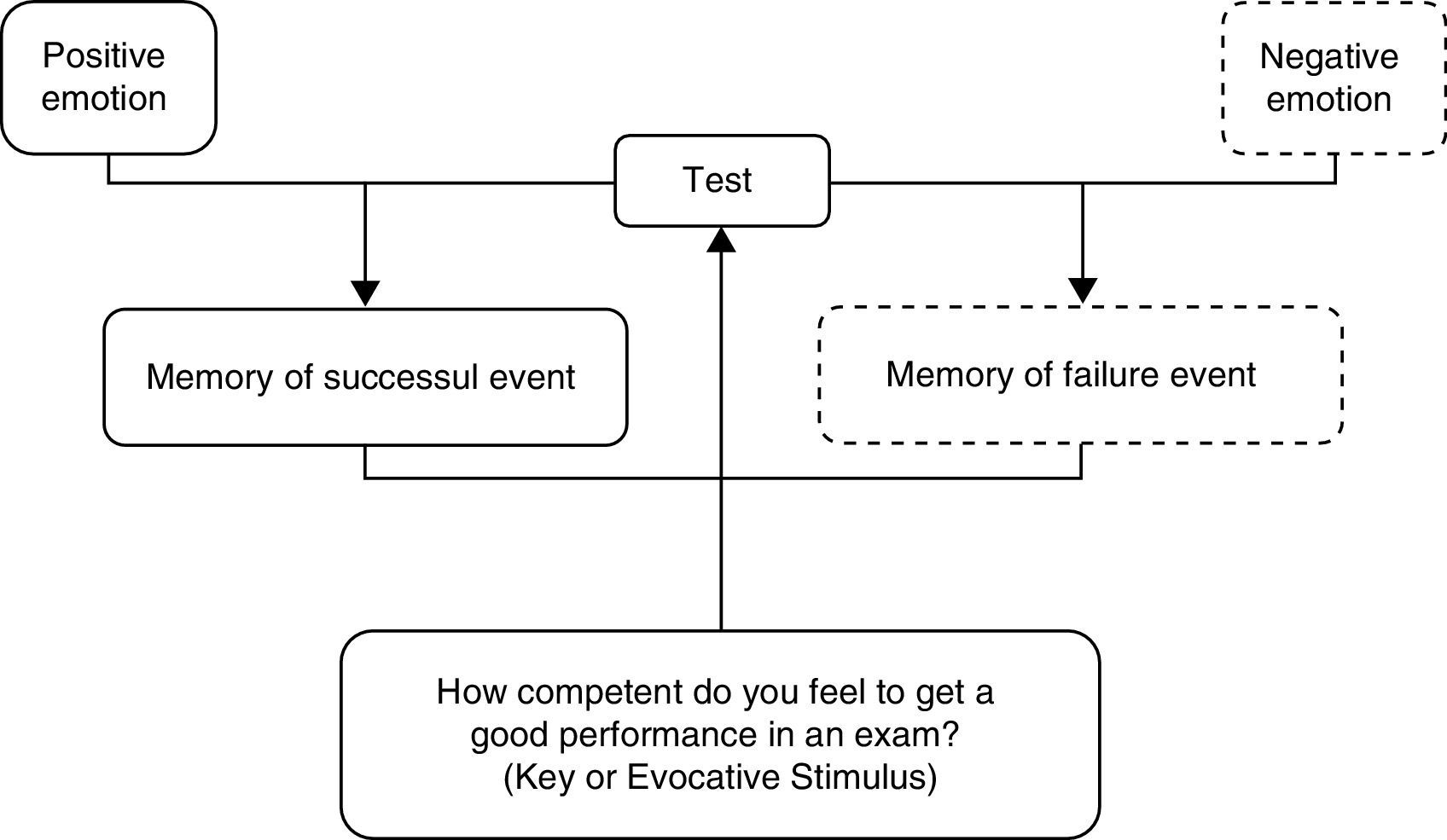

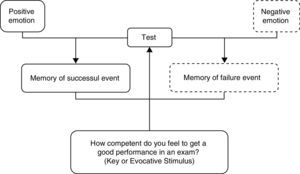

As suggested by Bandura (1997), the beliefs are formulated on the basis of previous experience. If the person has had previous failure experiences, he/she will feel less capable than if he/she has had previous successful experiences. However, it is possible to hypothesize that the emotional state inclines the collection of experiences of success or failure. For example, opposite to the question “How competent do you feel to get a good performance in an exam?” there is an activation of the concept “examination/test”, which belong to an associative network that include connections with autobiographical events of success (for example, obtaining a good score) and autobiographical events of failure (for example getting a bad qualification or not understanding a content). In turn, every event is associated with an emotional nodule which is in contact with positive and negative emotions, respectively (Figure 1).

Diagram of summation of activation.

Note. In this case, you could find the memories of previous experiences of success more accessible because this nodule is highly activated because of the concept of examination or test (activated by clues of the environment or evocative stimuli) and the positive emotional state.

The phenomenon of the mood state dependent memory occurs through a summation of the activation process motivated by the active concept, in this case “exam” or “test”, adding an immediate emotional state, turning more accessible to selective memories. Based on the memories of previous experience, the immediate emotional state could affect the judgments of self-efficacy. Hereby, if the person is in a positive emotional state, it is more likely that he/she remembers the successful event and, because of that, it could be activated by two different sources, the concept “examination/test” activated by clues of the environment and the nodule of positive emotion, and less probable that memories of the event of failure since it only would be activated by one source (the concept of exam activated by environmental clues).

Many studies have examined the relationship between positive and negative emotions with the judgments of self-efficacy. The methodological procedure used has been the same, i.e., the participants are induced to experience positive and negative emotions by methods of induction like music and/or movies, and then they are asked to communicate the confidence that they have to take different actions. In spite of the similarities in the methodological design used in some studies, the observed results are different. Some studies report that positive emotions reinforce the beliefs of self-efficacy and negative emotions discourage them (Baron, 1990). Other authors do not corroborate this effect (Cervone, Kopp, Schaumann, & Scott, 1994). Recently, Totawar and Nambudiri (2014) suggest that the hedonism levels and utilitarian motivation modulate the relationship between the mood states and the perception of self-efficacy. On the other hand, Jundt and Hinsz (2001) have found that the mood state correlates positively with the beliefs of self-efficacy in a worker sample.

We should consider that some theoretical and methodological aspects are not contemplated. First, many of the precedent studies do not work with specific judgments of self-efficacy, but they request that the participants evaluate their beliefs to execute them satisfactorily like intellectual, physical, and social general tasks, i.e, without delimiting clearly the behavior and contexts involved. Contrary to that, Bandura (1997) emphasizes that self-efficacy is a situational construct tied to behavioral delimited domains, and consequently it should be evaluated by instruments that contemplate such specificity. For this reason, in the present study we considered the beliefs of academic self-efficacy of college students, that involve three specific behavioral domains: 1) performance self-efficacy, i.e., the beliefs that the students have reached a good qualification (Pajares, 2003); 2) learning self-efficacy, about the beliefs to regulate their own actions and the necessary thoughts to reach the aims of learning (Zimmerman, 1995); and 3) social academic self-efficacy, related to the confidence that the students have to carry out social competent behaviors in the academic context (Solberg, O’Brien, Villareal, Kennel, & Davis, 1993). From the exposed above, it is hypothesized that the induction of positive and negative emotional states increase and decrease, respectively, the levels of academic self-efficacy of the college students (Hypothesis No. 1).

Besides, it should be considered that the exposure to a situation or stimulus potentially emotional is a necessary but not sufficient condition to induce an emotional response, and also the factors involved in the perception of the stimulus (Palmero & Martínez Sánchez, 2008). Some people differ substantially in their aptitude to perceive emotions and to control the mode and the intensity in which they are expressed (Hervás & Jódar, 2008). Thus, in this study the difficulties in the participants’ emotional regulation are included as a co-variable. Specifically, it is hypothesized that the capacity of emotional regulation modulates the effect of inductions of emotional states on the emotional condition (Hypothesis No. 2).

Finally, some factors can generate the absence of affective congruity identified by Bower and Forgas (2003). The Affect Infusion Model proposed specify some conditions in which the affect can influence and link the cognitive process, turning it into a coherent direction with the affect. According to this model, the infusion of affect is favorable when the emotional state is intense and when the task or cognitive judgment implies a constructive process. Hence, if the strategy of cognitive processing is direct and motivated (which carry a closed and directed process of search) it limits the opportunity of affective infusion. On the contrary, if the strategy of processing is heuristic and substantive, needing an open and constructive thought, it increases the possibility that the infusion of affection takes place. Opposite to this, we hypothesized that the effect of the emotional induction on judgments of self-efficacy will be most important in those participants having more intense emotional states (Hypothesis No. 3) and carrying a cognitive constructive strategy of processing (Hypothesis No. 4).

MethodParticipantsThe non-probabilistic accidental sample consisted of 50 college students (58% female, 42% male), aged between 17 and 31 years old (M=21.13, SD=4.58). After random assignment of participants to the condition of positive and negative induction, both groups belonged to similar socio-demographic characteristics. More specifically, the age of the positive induction group (M=21.11, SD=4.52) was equivalent to the age of the negative induction group (M=21.17, SD=4.81), showing no statistical difference (t=0.42, p>.96). Likewise, the gender of participants was balanced between the positive induction group (10 men) and negative induction group (11 men).

The participants agreed to volunteer in this study and received general information about the activities that they would carry out. It is necessary to clarify that some information related to the hypotheses was omitted to avoid expectations that could bias the results of the study. Once the experiment was up, all the participants received feedback of results obtained

InstrumentsSocial Academic Self-efficacy Scale (SA-SELF). It is a self-report instrument developed from a sample of the National University of Cordoba (Olaz & Medrano, 2007). The scale evaluates the students’ beliefs in their interpersonal capacities necessary for a suitable academic performance. The scale has 7 items, a unifactorial structure, and a good internal consistency (α=.84).

Self-Efficacy for Learning Scale (SELF-L). It consists of 10 items assessing the students’ perceived ability to be involved in learning processes such as planning, organization, and memorization. The SELF's brief Argentinean version adapted by Bugliolo and Castagno (2005) was used. This version was translated from the original version and the internal structure and internal consistency were calculated (α=.81).

Self-efficacy for Performance (SELF-P). It assesses the students’ beliefs in their aptitude to pass an exam and obtain good grades. It has 7 items that measure the students’ beliefs in their aptitude to pass a subject and to get a final average superior to 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. The items are arranged in an increasing difficulty. This instrument has been applied in the local population, and the results allow us to infer an unidimensional structure and a satisfactory internal consistency (α=.94).

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS). The adapted version of the instrument (Medrano & Trógolo, 2014) was used. It is composed of 28 items that present different difficulties to observe, evaluate, and modify emotional reactions. Exploratory factorial analyses revealed the presence of six underlying factors. The analyses of internal consistency revealed acceptable levels of consistency for the different factors (values between .70 and .87).

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS). This instrument came from an orthogonal model which suggests the existence of two independent factors: positive emotions (PE) and negative emotions (NE). The adapted version of PANAS has an acceptable internal consistency (α=.84 for NE, α=.75 for PE).

ProcedureAn experimental design taking the type of induced emotions (positive vs. negative) as independent variable was carried out. The manipulation of this variable was carried out combining movie and music. For the induction of emotional positive conditions the participants were exposed to comical scenes of the Argentinean humorist Alfredo Caseros and the Argentinean group Les Luthiers, and also an inspiring video of opera singer Paul Potts. Later, the participants listened to the 13th Serenade for Strings (“A Little Night Music”) of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in order to support the emotional positive tone.

The participants in the negative condition were exposed to fragments of the movie “Memory of the Plunder” of the Argentinean director Pino Solanas, which describes the problem of children malnutrition in Argentina. Later, the participants listened “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima” by the composer Krzystof Penderecki, to support the emotional tone. The selection of scenes of the movies and the songs was made on the basis of precedent studies (Eich & Schooler, 2003). Both procedures of induction have an approximate duration of 16minutes for showing the movie and then 10minutes for music.

After the showing of movies and paralleling the music session, the screen was used to show messages requiring to the participants to complete the Social Academic Self-efficacy, Performance Self-efficacy, Self-efficacy for Learning and Positive and Negative Affect scales, which were handed out in an envelope at the beginning of the experiment.

As for the ethical concerns, at the end of the questionnaires, the participants in the condition of negative induction were exposed to the positive induction videos with the aim of ending the experimental session in an emotional positive state.

In order to evaluate the modular role of the emotional regulation and the existence of a change in the emotional state after the induction, all the participants answered the DERS and PANAS scales before the emotional induction.

Data AnalysisThe information obtained was analyzed in two steps. First, the analyses attempted to evaluate the efficiency of the emotional induction, comparing the PANAS pretest and posttest measures using Student's t-test. Besides, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was used in order to determine if the difficulties of emotional regulation moderated the effect of emotional induction on emotional positive or negative condition of the participants. With this type of analysis it is possible to control the use of the linear regression to the variation of the dependent variables (in this case positive and negative emotions) produced by the covariables (in this case the difficulties of emotional regulation).

The second stage consisted of examining if the scores SA-SELF, SELF-P, and SELF-F were deferred significantly depending on the induction condition (positive vs. negative). For this, successive Student's t-tests were carried out for independent samples applying Holmes-Bonferroni's adjustment to maintain the type 1 error at p<.05.

ResultsControl Sociodemographic Variable: Equivalence of Group and Analysis of Impact on the Emotional ConditionTo control for the sociodemographic variables and other factors that could masked the variables, every participant was randomly assigned to every condition of positive and negative induction. After the random assignment, it was statistically corroborated if the distribution was equivalent in both groups. More specifically, the age of the positive induction group (M=21.11, SD=4.52) was equivalent to the age of negative induction group (M=21.17, SD=4.81), showing no statistical difference (t=0.42, p>.96). Likewise, the gender of participants was balanced between the positive induction group (10 men) and negative induction group (11 men), the equivalence being corroborated again between the groups in relation to sex (χ2=0.800, df=1, p = .37).

Finally, to check that changes in the emotional condition were not attributable to the sociodemographic variables, a hierarchical regression analysis was realized, with the variables of sex, age, and experimental condition being included sequentially. The results indicate that sex only explains 2% of change in the affective condition, F(1, 40)=0.83, p=.37, including the variable age; the explanatory value is increased by 4%, being not significant, F(2, 39)=0.85, p=.43. Only by including in the model the variable of experimental condition, a significant increase is observed, F(3, 38)=21.43, p<.00, of the explanatory power, explaining 63% of the variability.

Efficiency of the Emotional Induction and Moderating Effect in the Capacity of Emotional RegulationWe did not observe statistic differences in the levels of positive emotions in the PANAS pretest measurements (t=.50, df=48, p>.62) as well as in the levels of negative emotions (t=.22, df=48, p>.83). After the emotional induction the group exposed to the condition of positive induction obtained higher scores in the scale of positive emotions (ME=32.85, SD=8.24), with respect to the group exposed to the negative induction (ME=28.82, SD=4.20). The difference was significant (t=2.02, df=48, p<.05) and moderate considering the effect size of the difference (d=0.62).

By contrast, the group exposed to the condition of negative induction obtained higher scores in the scale of negative emotions (ME=27.07, SD=7.02) compared to the group exposed to the positive induction (ME=16.28, SD=3.37). The difference was significant (t =7.26, df=48, p<.001, d=1.95).

To determine if the effect of emotional induction on emotional response was modulated by the capacity of emotional regulation of the participants, a MANCOVA was carried out considering the condition of emotional induction (positive vs. negative) as independent variable, the difficulties of emotional regulation measured by DERS as covariables, and the PANAS scores after the emotional inductions as dependent variables.

The Box's M statistic was significant (25.98, p<.00), which suggests the fulfillment of the homogeneity assumption of the variance-covariance matrix. MANCOVA multivariable contrasts indicate a moderate and significant effect of the condition emotional induction (Wilks’ lambda=.388, F(2, 41)=32.30, p<.001, ¿2=.61, observed potential=1). Besides, a significant effect was observed, although small, of covariables “limited access to strategies of emotional regulation” (Wilks’ lambda=.799, F(2, 41)=5.15, p<.001, ¿2=.20, observed potential=1) and “difficulties in the impulses control” (Wilks’ lambda=.805, F(2, 41)=4.95, p<.001, ¿2=.19, observed potential=1).

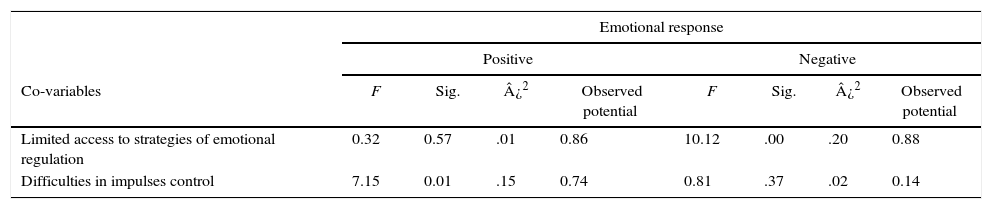

The unvaried contrasts presented in Table 1 suggest that the effect of the covariable “limited access to strategies of emotional regulation” is only significant for emotional negative answers, whereas the covariable “difficulties in impulses control” only have a significant effect on the emotional positive response

Unvaried Contrasts of Significant Covariables of MANOVA.

| Emotional response | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||||

| Co-variables | F | Sig. | ¿2 | Observed potential | F | Sig. | ¿2 | Observed potential |

| Limited access to strategies of emotional regulation | 0.32 | 0.57 | .01 | 0.86 | 10.12 | .00 | .20 | 0.88 |

| Difficulties in impulses control | 7.15 | 0.01 | .15 | 0.74 | 0.81 | .37 | .02 | 0.14 |

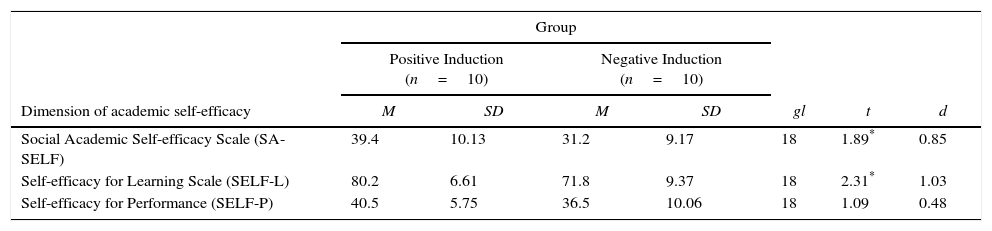

In order to compare the self-efficacy scales scores (SA-SELF, SELF-P, and SELF-L), the participants were classified according to the emotional induction (positive vs. negative), and no statistically significant results were obtained. Apparently, the induction of an emotional positive or negative state did not generate an impact on beliefs of academic self-efficacy. However, when the analyses with 20 cases that experienced a more intense emotional state were replicated, significant differences were observed in scores of SA-SELF and SELF-L, and values of size of the effect was high (Table 2).

Effects of Emotional Induction on the Beliefs of Self-efficacy in Cases with more Intense Emotional State.

| Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Induction (n=10) | Negative Induction (n=10) | ||||||

| Dimension of academic self-efficacy | M | SD | M | SD | gl | t | d |

| Social Academic Self-efficacy Scale (SA-SELF) | 39.4 | 10.13 | 31.2 | 9.17 | 18 | 1.89* | 0.85 |

| Self-efficacy for Learning Scale (SELF-L) | 80.2 | 6.61 | 71.8 | 9.37 | 18 | 2.31* | 1.03 |

| Self-efficacy for Performance (SELF-P) | 40.5 | 5.75 | 36.5 | 10.06 | 18 | 1.09 | 0.48 |

Note. In all cases homoscedasticity of Levene's test was not significant.

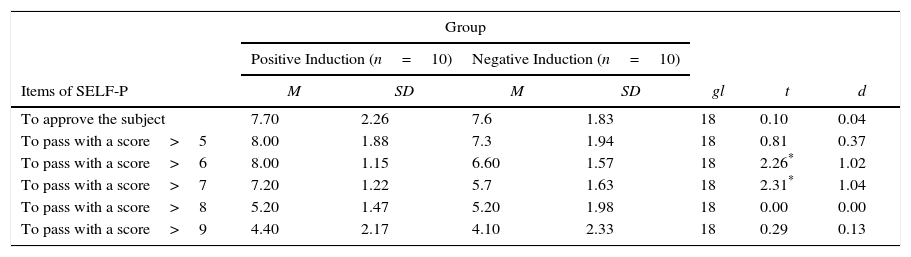

Considering that SELF-P was the only dimension of the academic self-efficacy where no significant differences were found, successive Student's t-tests were carried out to examine in depth the performance of this variable (Table 3). Comparing both conditions, significant differences were not observed in the easiest items of the SELF-P (“to pass the subject” and “to pass with a grade higher than 5”), nor in the most difficult items (“to pass with a grade higher than 8”, and “to pass with a grade higher than 9”). However, significant differences were observed in the intermediate difficulty items of (“to pass with a grade higher than 6”, and “to pass with a grade higher than 7”).

Effects of Emotional Induction on the Different Items of the Beliefs of Self-efficacy for Performance in Cases with more Intense Emotional State.

| Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Induction (n=10) | Negative Induction (n=10) | ||||||

| Items of SELF-P | M | SD | M | SD | gl | t | d |

| To approve the subject | 7.70 | 2.26 | 7.6 | 1.83 | 18 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| To pass with a score>5 | 8.00 | 1.88 | 7.3 | 1.94 | 18 | 0.81 | 0.37 |

| To pass with a score>6 | 8.00 | 1.15 | 6.60 | 1.57 | 18 | 2.26* | 1.02 |

| To pass with a score>7 | 7.20 | 1.22 | 5.7 | 1.63 | 18 | 2.31* | 1.04 |

| To pass with a score>8 | 5.20 | 1.47 | 5.20 | 1.98 | 18 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| To pass with a score>9 | 4.40 | 2.17 | 4.10 | 2.33 | 18 | 0.29 | 0.13 |

Note. In all cases homoscedasticity of Levene's test was not significant.

The results obtained at the first glance would lead us to think that it was not possible to observe the influence of the mental condition on judgments of academic of self-efficacy measured in its three dimensions (i.e., social academic self-efficacy, self-efficacy for learning, and performance self-efficacy). However, recently a theoretical model called the third generation has been proposed (Forgas, 2000), which allows us to understand in a more complex way the relation between the affect and cognition. One of these models is the already mentioned Affect Infusion Model (AIM) (Bower & Forgas, 2003;Forgas, 2000). The AIM was developed as a comprehensive and integrative theory to explain both the presence and the absence of affective infusion in cognition (Forgas, 2000). This was considered in order to explain some of the findings in the present study. Likewise, the developments of Eich and Macaulay (2000) and Eich and Schooler (2003) were considered, indicating that there are two important factors involved in the relation between affect and cognition, getting a better understanding of the results. In relation to the above mentioned, on one hand, the task relative factors can be found, which have been considered in depth by AIM to explain the choice of one or another type of processing (e.g., noun or motivated) and the probability of affective infusion in cognition (Bower & Forgas, 2003). On the other hand, there is the relative factors in the mood state (e.g., forces factor) described by Eich and Macaulay, and Eich and Schooler.

Regarding task relative factors, the Affect Infusion Model of Forgas (2001) indicates that the tasks that should demand a more substantial strategy of processing increase the probability to induce the affective infusion. In this sense, a series of variables was proposed that facilitate the choice of this type of processing (Bower & Forgas, 2003). Among these variables, the complexity or typical character of the task, which indicates that the bias of mental congruity, has been found to be more probable when the complex and/or atypical tasks are present. This allows us to explain the results found in Self-efficacy for Performance (SELF-P), because the items in which the students were more successful in their performance (i.e., “to pass the subject”, “to pass with a score higher than 5”, “to pass with a score higher than 8” and “to pass with a score higher than 9”), did not present a coherent bias with the mental condition, whereas for those items in which the students are supposed to be less successful in their performance (i.e., “to pass with a score higher than 6” and “to pass with a score higher than 7”) a coherent bias with the mental predominant state can be estimated. Considering the AIM, it suggests that the person uses a more elaborated processing to answer the items of intermediate difficulty of SELF-P. As Bower and Forgas (2003) explained, this type of processing is more able to make a cognitive evocation derived from the affects that influence the interpretation of the information.

In relation to the factors relative to mood state, one of the remarkable aspects that has been pointed out is related with the force factor of mental condition (Eich & Macaulay, 2000; Eich & Schooler, 2003). It postulates that the probability to find a coherent result with the mental condition increases when there is an affective manipulation of mood state, i.e., the more intense is the inducted mood state, the more probable is the affective infusion in cognition. This has been proposed in relation to the phenomenon called mood state-dependent memory (MDM), suggesting that the same is valid for the mood-congruent events. According to this, when the 20 participants that experienced more intense mood state were considered, an affective coherent bias with the mental condition in the majority of dimensions in the academic self-efficacy (e.g., Social Academic Self-efficacy and Self-efficacy for Learning) could be shown.

Finally, this paper suggests that the capacity for emotional regulation could modulate the effect of the emotional states inductions on the emotional state. The results obtained support this hypothesis. As it was observed, a significant effect was obtained, although it is small in covariables “limited access to strategies of emotional regulation” and “difficulties in impulses control”, the effect of the first one (“limited access to strategies of emotional regulation”) being only significant for emotional negative answers, whereas the second one (“difficulties in impulses control”) only showed a significant effect on emotional positive response. As Erber and Erber (2001) suggest, people seem not to experience mood states in an invariant and automatic way, but in a controlled, manageable, or regular way.

In summary, we can conclude that the induction of positive and negative mood states increases and diminishes, respectively, the levels of academic self-efficacy in college students. However, this was only observed in participants that demonstrate a condition of intense or raised mood and in those atypical or slightly accurate items of character. Finally, we also conclude that the difficulty in the emotional regulation modulates the effect of inductions of mood states, both in a positive and negative manner.

Resumen extensoNumerosos estudios han examinado la relación existente entre emociones positivas y negativas con los juicios de autoeficacia. En general el procedimiento metodológico utilizado ha sido el mismo: los participantes son inducidos a experimentar emociones positivas y negativas mediante métodos de inducción y luego deben comunicar la confianza que poseen para ejecutar diversas acciones. Sin embargo, cabe considerar algunos aspectos teóricos y metodológicos no contemplados. En primer lugar, muchos de los estudios antecedentes no trabajan con juicios específicos de autoeficacia sino que solicitan a los participantes que evalúen sus creencias para ejecutar satisfactoriamente tareas intelectuales, físicas y sociales generales, es decir, sin delimitar con claridad las conductas y contextos involucrados. Por el contrario, Bandura (1997) destaca que la autoeficacia es un constructo altamente situacional y ligado a dominios conductuales delimitados, por lo que, en consecuencia, deben ser evaluadas por medio de instrumentos que contemplen tal especificidad. Por ello en el presente trabajo se considerarán las creencias de autoeficacia académica de los estudiantes universitarios, las cuales involucran tres dominios conductuales específicos: 1) autoeficacia para el rendimiento, es decir las creencias que poseen los estudiantes de alcanzar una buena calificación, 2) autoeficacia para la autorregulación del estudio, entendida como las creencias para regular las propias acciones y pensamientos necesarios para alcanzar las metas de aprendizaje y 3) autoeficacia social académica, la cual refiere a la confianza que poseen los estudiantes para llevar a cabo comportamientos sociales competentes en el contexto académico. A partir de los desarrollos anteriormente expuestos se hipotetiza que la inducción de estados emocionales positivos y negativos aumentará y disminuirá, respectivamente, los niveles de autoeficacia académica de los estudiantes universitarios (hipótesis 1).

Sumado a lo anterior debe considerase que la ocurrencia de una situación o estímulo potencialmente emocional es una condición necesaria pero no suficiente para alcanzar una respuesta emocional. Deben considerase también los factores involucrados en la percepción del estímulo. Tomando esto en consideración, en este estudio se incluye como covariable las dificultades en la regulación emocional que poseen los participantes. Concretamente, se hipotetiza que la capacidad de regulación emocional modulará el efecto de las inducciones de estados emocionales sobre el estado emocional de los mismos (hipótesis 2).

Finalmente resta considerar algunos factores identificados por Bower y Forgas (2003) que pueden provocar la ausencia de congruencia anímica. El modelo de infusión del afecto propuesto especifica algunas condiciones bajo las cuales el afecto puede influir e incorporarse al proceso cognitivo inclinándolo en una dirección congruente con el afecto. Según este modelo la infusión del afecto se ve favorecida cuando el estado emocional es intenso y cuando la tarea o juicio cognitivo implica un procesamiento constructivo. De esta forma si la estrategia de procesamiento cognitivo es directa y motivada (conlleva un proceso de búsqueda cerrado y dirigido) se limita la oportunidad de infusión afectiva. Por el contrario si la estrategia de procesamiento es heurística y sustantiva (requiere un pensamiento abierto y constructivo) aumenta la posibilidad de que se produzca infusión del afecto. Frente a ello se hipotetiza que el efecto de la inducción emocional sobre los juicios de autoeficacia será mayor en los participantes con estados emocionales más intensos (hipótesis 3) y que conlleven una estrategia cognitiva de procesamiento constructiva (hipótesis 4).

MétodoSe llevó a cabo un diseño experimental considerando como variable independiente el tipo de emociones inducidas (positivas vs. negativas). La manipulación de esta variable se efectuó a través de la exposición combinada de película/música.

Luego de la proyección de películas y al comenzar la inducción de música aparece en la pantalla un mensaje que solicita a los participantes que respondan a los cuestionarios de Autoeficacia Social Académica (ASA), Autoeficacia para el Rendimiento (EAR), Autoeficacia para el Aprendizaje (SELF-A) y la escala PANAS, los cuales son entregados en un sobre cerrado al inicio del experimento.

Con el objeto de evaluar el rol modular de la regulación emocional y la existencia de un cambio en el estado emocional luego de la inducción, todos los participantes respondieron a la escala DERS y PANAS antes de la inducción emocional.

Los datos recabados fueron analizados en dos etapas. En primer lugar se llevaron a cabo análisis tendientes a evaluar la eficacia de la inducción emocional comparando las medidas pretest y postest del PANAS mediante una prueba t de Student. Sumado a ello se realizó un análisis multivariado de co-varianza (MANCOVA) con el fin de determinar si las dificultades de regulación emocional moderan el efecto de la inducción emocional sobre el estado emocional positivo o negativo de los participantes.

La segunda etapa de análisis estadístico consistió en examinar si diferían significativamente los puntajes del ASA, EAR y SELF-F en función de la condición de inducción (positivo vs. negativo). Para esto se llevaron a cabo sucesivas pruebas t de Student para muestras independientes aplicando un ajuste de Holmes-Bonferroni para mantener el error tipo 1 en un nivel p < .05.

Resultados y DiscusiónLos resultados obtenidos en una primera instancia llevarían a pensar que no pudo verificarse la influencia del estado anímico sobre los juicios de autoeficacia académica medido en sus tres dimensiones (i.e., autoeficacia social académica, autoeficacia para el aprendizaje y autoeficacia para el rendimiento). Sin embargo, recientemente se han propuesto modelos teóricos denominados de tercera generación que permiten comprender de una manera más compleja la relación entre el afecto y la cognición. Uno de estos modelos es el Modelo de Infusión del Afecto (MIA). Asimismo, se consideraron los desarrollos de Eich y Macaulay (2000) y Eich y Schooler (2003), quienes señalan dos factores de importancia implicados en la relación entre el afecto y la cognición. En relación con esto último, se encuentran los factores relativos a la tarea, que han sido considerados en profundidad por el MIA con el fin de explicar la elección de uno u otro tipo de procesamiento y la probabilidad de infusión afectiva en la cognición y, por otro lado, están los factores relativos al estado de ánimo descritos por Eich y Macaulay y Eich y Schooler.

Con respecto a los factores relativos a la tarea, el modelo de infusión del afecto de Forgas (2001) indica que las tareas que demanden una estrategia de procesamiento más sustantiva aumentan la probabilidad que se presente la infusión afectiva. En este sentido, se han propuesto una serie de variables que facilitan la elección de este tipo de procesamiento. Entre estas se encuentra la complejidad o carácter típico de la tarea, que señala que los sesgos de congruencia anímica son más probables cuando se presentan tareas complejas o atípicas. Esto permite entender los resultados encontrados en la autoeficacia para el rendimiento (EAR), dado que los ítems en los cuales los estudiantes pueden tener más certezas sobre su desempeño no presentaron un sesgo congruente con el estado anímico, mientras que para aquellos ítems en los que se supone los estudiantes tendrían menor certeza sobre su desempeño puede apreciarse un sesgo congruente con el estado anímico predominante. Tomando en consideración el MIA puede pensarse que para responder los ítems de dificultad intermedia del EAR el sujeto utiliza un procesamiento más elaborado.

En relación a los factores relativos al estado de ánimo, uno de los aspectos señalados tiene que ver con el factor fuerza del estado anímico. Partiendo de estos postulados, puede afirmarse que la probabilidad de encontrar resultados congruentes con el estado anímico aumenta cuando hay una manipulación afectiva del estado de ánimo. En otras palabras, mientras más intenso sea el estado de ánimo inducido más probable es la infusión afectiva en la cognición. Si bien esto ha sido propuesto en relación al fenómeno de memoria dependiente del estado de ánimo (MDM), cabe suponer que lo mismo es válido para los sucesos de congruencia anímica. En este sentido, cuando se consideraron los 20 sujetos que manifestaron un estado de ánimo más intenso pudo corroborarse un sesgo afectivo congruente con el estado anímico en la mayoría de las dimensiones de la autoeficacia académica.

Por último, se ha propuesto también en este trabajo que la capacidad de regulación emocional modularía el efecto de las inducciones de estados emocionales sobre el estado emocional. Los resultados apoyan de cierta forma estos supuestos. Como pudo observarse, se verificó un efecto significativo aunque pequeño de las covariables “acceso limitado a estrategias de regulación emocional” y “dificultades en el control de impulsos”, siendo el efecto de la primera sólo significativo para respuestas emocionales negativas, mientras que la segunda sólo mostró un efecto significativo sobre la respuesta emocional positiva. Así, las personas parecen no experimentar sus estados de ánimo de manera invariante y automática sino que lo hacen de una manera controlada, manejable o regulada.

En síntesis, puede concluirse que la inducción de estados de ánimo positivos y negativos aumenta y disminuye, respectivamente, los niveles de autoeficacia académica de los estudiantes universitarios (hipótesis1). Sin embargo, esto sólo se observa en los sujetos que manifiestan un estado de ánimo intenso o elevado y en aquellos ítems de carácter atípicos o poco certeros (hipótesis3 y 4). Por último, se concluye también que la dificultad en la regulación emocional modula el efecto de las inducciones de estados de ánimo (hipótesis2), tanto en el estado de ánimo positivo como en el estado de ánimo negativo.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

This study was supported by grants from Universidad Empresarial Siglo XXI.