Aortic stenosis is the most common primary valvulopathy worldwide. It has an estimated prevalence of 7.6 million people over the age of 75 in Europe and the United States, and the increased life expectancy of the world¿s population will cause this rate to continue to increase1.

Approximately 50% of patients are asymptomatic when diagnosed with this valvulopathy, and many may have a preserved ejection fraction (EF). This type of patients has been classified as stage C1, according to the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) guidelines. Management consists of clinical and echocardiographic follow-up every six to twelve months (a recommendation made by experts and based on retrospective studies)2. However, those with a low surgical risk (score <4 according to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons – STS) and who have additional poor prognostic factors such as symptoms triggered by a stress test, severe valve calcification with restricted opening, transvalvular flow velocity> 5 m/s, mean gradient> 60mm Hg, and an increase in valvular flow velocity of more than 0.3 m/s/year, benefit from early valve replacement3.

Recently, the 2017 AHA/ACC guideline update recommended surgical aortic valve replacement for both symptomatic (stage D) and asymptomatic (stage C) patients with severe aortic stenosis who meet some surgical indication, as long as the surgical risk is low or intermediate3. This recommendation could be interpreted in two ways: all patients with severe aortic stenosis, regardless of symptoms, should undergo surgical aortic valve replacement; or asymptomatic patients should have some poor prognostic factor in order to undergo surgery. The latter interpretation is the one that agrees with the 2014 guideline text. For their part, the 2017 European Society of Cardiology guidelines4 proposed that observation in patients without poor prognostic factors appears to be safe, while it is unlikely that early surgery would provide a benefit.

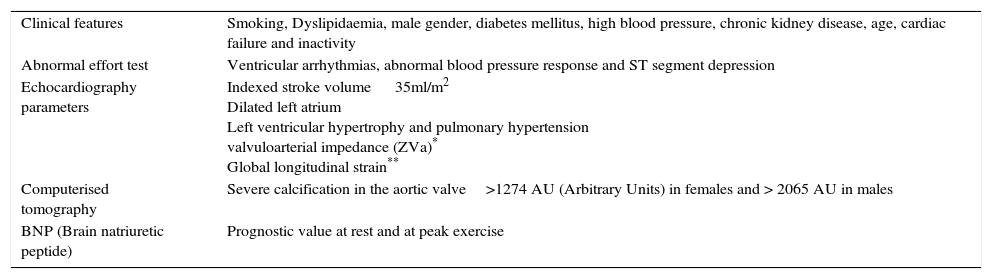

What should I know while I observe?It is important to remember that the risk of sudden death in these patients is 1-1.5% per year, and that there are certain factors that make the follow-up strategy difficult, such as the interpretation and variable progression of clinical manifestations, irreversible intrinsic myocardial damage once symptomatology appears, and increased surgical risk with increasing age5. Furthermore, when symptoms begin, the risk of sudden death doubles in the first three to six months, and approximately 6.5% die waiting for surgical aortic valve replacement6. This is why other clinical, paraclinical and imaging parameters have been exhaustively studied in recent years: parameters related to a poor prognosis and rapid progression, which may, in turn, help to define the need for early surgical aortic valve replacement in this group of patients during clinical observation5 (table 1).

Parameters of poor prognosis and rapid progression in patients with asymptomatic severe AS

| Clinical features | Smoking, Dyslipidaemia, male gender, diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, age, cardiac failure and inactivity |

| Abnormal effort test | Ventricular arrhythmias, abnormal blood pressure response and ST segment depression |

| Echocardiography parameters | Indexed stroke volume 35ml/m2 Dilated left atrium Left ventricular hypertrophy and pulmonary hypertension valvuloarterial impedance (ZVa)* Global longitudinal strain** |

| Computerised tomography | Severe calcification in the aortic valve>1274 AU (Arbitrary Units) in females and > 2065 AU in males |

| BNP (Brain natriuretic peptide) | Prognostic value at rest and at peak exercise |

A recent meta-analysis compared the conservative strategy to early surgical aortic valve replacement, (defined in only two studies as intervention within three months after diagnosis), and found a risk of mortality due to any cause 3.5 times greater in patients assigned to a conservative strategy5. However, a new meta-analysis which compared these two strategies only found a tendency toward lower mortality due to any cause in patients undergoing early surgical aortic valve replacement compared to surgical aortic valve replacement guided by symptoms, with no significant difference in the outcome of death due to cardiovascular causes or sudden death7. These meta-analyses are based on observational studies, making it difficult to draw accurate conclusions regarding the best strategy for this group of patients. Thus, the previously mentioned parameters, as well as new individual selection routes based on metabolic needs and fragility, could be a key towards a more objective assessment to help determine the need for early surgical aortic valve replacement.

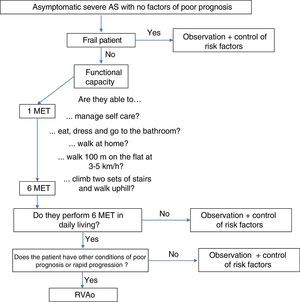

New routes for follow-up of asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosisAn individual and integral assessment of these patients should include fragility and basal metabolic rate. Recently, fragility scales have emerged to evaluate candidates for TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) which could be used to guide the treatment strategy for this group of patients, since the more fragile they are, the easier it will be to decide to just observe them.

Likewise, there are scales that estimate functional capacity, measured in metabolic equivalents (METS), which can be used to estimate the daily activity of asymptomatic patients in their everyday life8. In a patient without high metabolic requirements, in whom symptoms will probably not develop, the assessment of other prognostic parameters will possibly not be necessary, and therefore observation and control of clinical risk factors could be sufficient, rather than submitting him/her to an unnecessary surgical risk (fig. 1). However, studies evaluating the usefulness of these variables in the decision algorithm would be necessary.

Pathophysiology of risk factors in aortic stenosis. Should we control them while we observe?The concept of the osteogenic process is the key to the pathogenic response to the lesion in fibrocalcifying valvular disease, in which many studies have shown an increased expression of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), arising from the endothelium of the aortic portion of the valve9. These pro-osteogenic processes are guided by direct inhibitors of osteogenic signaling, inflammatory cells, proinflammatory cytokines, angiotensin II, oxidative stress and matrix degrading enzymes, which, in turn, are related to controllable risk factors such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hiperlipidemia and smoking10. In this sense, knowing beforehand that there is no established medical treatment to prevent disease progression or delay the need for surgical aortic valve replacement, the control of risk factors during a period of observation could at least delay the manifestation of symptoms, which in many contexts appear with decompensation or poor control of the risk factors.

The various interpretations that can be given to the management of patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis and a preserved ejection fraction reflect the fact that there is still no categorical evidence to indicate that early surgical aortic valve replacement is the definitive answer to this question, and show the need to develop and validate new follow-up routes to help define and guide the treatment algorithms. Whether it is better to observe than to operate is still unknown, but what is certain is that individualizing the patient in a context of multidisciplinary management and ¿heart team¿ could produce better results.