To establish associations between the development of lupus nephritis (LN) and the expression of antibodies against C1q (anti-C1q) and serum adiponectin as these biomarkers have been previously postulated to be associated with the presence of LN.

MethodologyA case–control study nested in a cohort was chosen. Patients with SLE with renal involvement were included. Measurement of antibodies against C1q, levels of adiponectin, and HLA expression DRB1 and DQB1 were evaluated. We searched for possible associations between the measured biomarkers and allelic HLA types found.

ResultsOne hundred and six patients were recruited with LN with a mean age of 35 years. Mean adiponectin levels were 16.9μg/mL, and 60% of patients presented anti-C1q positivity. HLA DRB1*0404 and DRB1*1101 are protective factors for LN (OR: .42, p=.0030 and OR: 0.49, p=.046 respectively). HLA DRB1*0701 (OR: 3.15, p=.0452) and DRB1*0802 (OR: 8.3, p=.020) are susceptibility factors for LN. There was a tendency for association between anti-C1q positivity and high levels of adiponectin with type IV LN (OR 2.3 [95% CI: 0.68–8.2] and (OR: 2.67 [95% CI: .76–9.9] respectively). There was a tendency for association between anti-C1q positivity and HLA expression DRB1*0701 (OR 2.7 [95% CI: .81–11.5]), as well as high levels of adiponectin and HLA expression DRB1*0404 (OR 3.03 [95% CI: .92–12.8]). No association was found between anti-C1q and adiponectin with the expression of HLA DRB1*1501. There was positive correlation between levels of anti-C1q and the activity index in renal biopsy.

ConclusionsIn the Colombian population there is a tendency for association of anti-C1q with the expression of HLA DRB1*07; however, the expression of other HLA II genes known as risk factors for LN, was not associated with the expression of anti-C1q, adiponectin or any specific type of LN.

Establecer asociaciones entre la aparición de nefritis lúpica (LN) y la expresión de biomarcadores previamente postulados como asociados con la presencia de esta enfermedad. A su vez, determinar en población colombiana si dicha expresión se relaciona con algún tipo específico de HLA II.

MetodologíaEstudio de casos y controles anidados en una cohorte, pacientes con LES que cumplen los criterios diagnósticos del Colegio Americano de Reumatología y que presentan compromiso renal. Se realizó una medición de anticuerpos contra C1q y niveles de adiponectina en suero por medio de ELISA. Se evaluó expresión de HLA DRB1 y DQB1. Se buscaron las posibles asociaciones entre los biomarcadores medidos y las variables alélicas de HLA, además de las posibles correlaciones de los biomarcadores con otros anticuerpos o variables de daño renal.

ResultadosCiento seis pacientes reclutados con LN (81% mujeres), con un promedio de edad de 35 años. Los niveles promedio de adiponectina fueron 16,9 ug/mL, el 60% de los pacientes presentaron anti-C1q positivos. Hubo tendencia a la asociación entre anti-C1q positivos y niveles elevados de adiponectina con LN tipo IV (OR 2,3 [IC 95%: 0,68-8,2] y OR: 2,67 [IC 95%: 0,76-9,9], respectivamente). Hubo tendencia a la asociación entre anti-C1q positivo y expresión de HLA DRB1*0701 (OR 2,7 [IC 95%: 0,81-11,5]), así como niveles elevados de adiponectina y expresión de HLA DRB1*0404 (OR 3,03 [IC 95%: 0,92-12,8]). No se encontró asociación entre anti-C1q y adiponectina con la expresión de HLA DRB1*1501. Hubo correlación positiva entre los niveles de anti-C1q y el índice de actividad en biopsia renal.

ConclusionesEn población colombiana, hay un tendencia a la asociación entre la presencia de anti-C1q y los niveles elevados de adiponectina con LN en sus formas proliferativas. Hay una tendencia a la asociación de anti-C1q con la expresión de HLA DRB1*07; sin embargo, la expresión de otros genes HLA II, conocidos como factores de riesgo para LN, no estuvo asociada con la expresión de anti-C1q, adiponectina o algún tipo específico de LN.

In chronic diseases whose pathophysiology is often not entirely clear, making an early diagnosis becomes a priority to stop the progression of the disease and improve patient's life quality. The autoimmune diseases are a clear example of this situation, however, despite this fact is clearly recognized and accepted, there are limitations to early identification of these diseases and stopping their progression.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is not alien to this reality, including lupus nephritis (LN), one of its most frequent manifestations. Currently the diagnosis of LN is made through renal biopsy, abnormal urinalysis, or increase in creatinine levels. However, all the diagnostic tools available to diagnose LN do not allow an early detection of renal involvement; since the suggestive clinical manifestations, that lead the clinician to ordering a renal biopsy, only appear in advanced stages of the disease.1,2 Especially the elevation of creatinine levels, which is the result of an important glomerular compromise, that in turn means many patients will already end up in renal replacement therapy or kidney transplant, when detected. In recent years, many efforts have been made to establish biomarkers associated with renal activity of SLE in order to optimize diagnosis and treatment. Several different autoantibodies, proteomic and genetic markers have been postulated.3,4 Despite this, there are very few studies that seek to determine if these biomarkers behave as predictors of the appearance of LN, which would allow optimizing the approach to the disease and early intervention strategies to improve the prognosis of patients.5 In Latin America, especially in Colombia, there are limited studies that have attempted to establish the association of such antibodies with the presence of LN. Neither are there many studies that seek to define if there is any relationship with the genetic characteristics of the local population.

This study corresponds to the first phase of a research line that seeks to clarify the uncertainties related to LN. The aim of this study is to establish associations between the appearance of LN and the expression of antibodies against C1q (anti-C1q) and serum adiponectin, previously postulated as biomarkers associated with the presence of LN. Additionally, determine if the expression of these is related to some specific type of HLA II in the Colombian population.

MethodologyPatientsA nested case–control study was conducted in a cohort with Colombian patients diagnosed with SLE according to the 2019 ACR/EULAR criteria.6 Patients were recruited from three hospitals in two cities of the country. Patients older than 18 years were included, who presented a first episode of active LN, and accepted to sign freely and voluntarily the informed consent according to the declaration of Helsinki. We excluded pregnant patients, active infection, diagnosis of another connective tissue disease, kidney disease of another etiology, or use of nephrotoxic drugs. When was available, a renal biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. In the sera of all patients, the concentration of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antibodies against double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), complement levels C3 and C4, anti-C1q, adiponectin, HLA DRB1* and HLA-DQB1* were measured at time of diagnosis of LN. As well as the laboratory procedures that the treating group considered necessary. We also included a control group of healthy patients and SLE patients without LN who were tested for HLA DRB1* and HLA-DQB1*. Healthy control group matched for age and sex was recruited through active search within the participating institutions. People with a family history of autoimmunity were excluded from healthy control group.

Definition of variablesLN was defined as evidence of proteinuria greater than 0.5g in 24h, presence of urinary sediment with glomerular hematuria or cylindruria, and/or creatinine greater than 1.5mg/dL in patients with SLE in absence of other pathologies that explain the previously mentioned alterations.2 The cases were defined as all the patients who presented the association of interest to be evaluated, and controls to all the patients who did not present this association. For the HLA II analysis, all patients with LN were defined as a case, and patients with SLE without LN and healthy controls were defined as control groups.

Measurement of anti-C1q, adiponectin, HLA and other laboratory parametersThe concentration of anti-C1q levels was made through the ELISA technique with the kit (ORGENTEC Diagnostika GmbH from Germany), values greater than or equal to 10U/mL were taken as positive according to supplier's specifications. The measurement of serum adiponectin levels was made through the ELISA technique with a kit from the same commercial house (DIA Source from Belgium), values of 8.33μg/mL±2.41 were taken as normal following the supplier's recommendations. HLA DRB1* and HLA-DQB1* genotyping was performed in all patients using the luminex technology in a reference center in Barranquilla. The sera were properly stored and transported to the reference center of the Universidad del Norte in the city of Barranquilla until the measurement of anti-C1q, adiponectin, HLA were carried out. The measurements of C4 and C3 were quantified through nephelometry. The rest of the laboratory parameters were determined through routine laboratory procedures at the time of the patient presented LN. Renal biopsies were reported according to the classification systems of the International Society of Nephrology and the International Society of Pathology.7

Statistic analysisThe clinical and demographic variables are presented as mean, ranges or percentages according to most convenient measure for the results. Odds ratio (OR) was calculated as a measure of association. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to perform the different comparisons between clinical variables when necessary. Spearman correlation test was used to evaluate the possible correlations. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the statistical measurements were carried out through the statistical program STATA 15.0 (from United States).

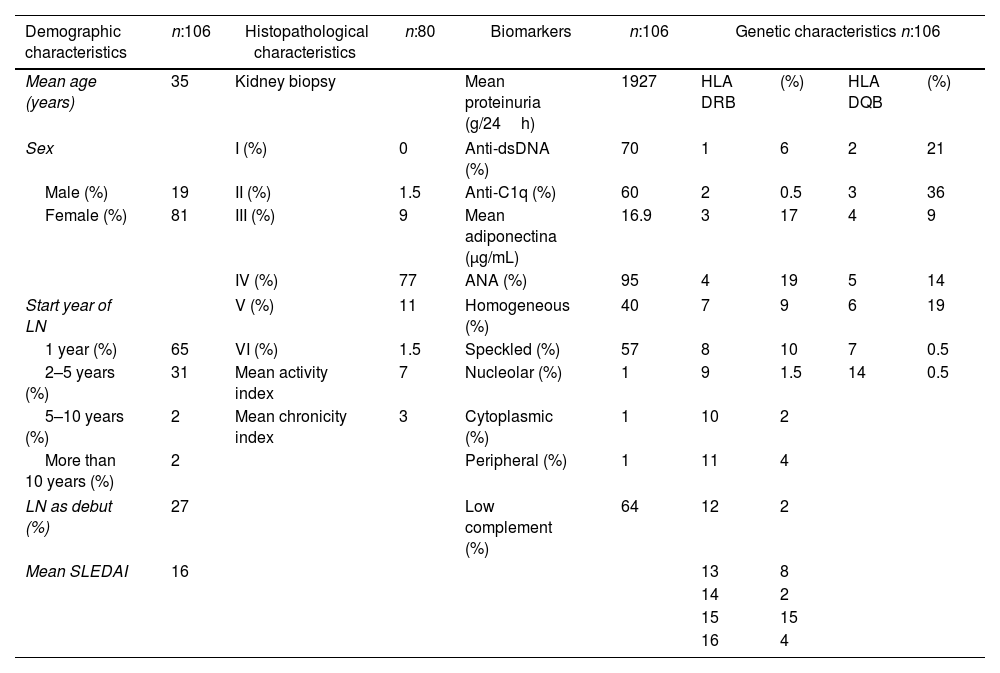

ResultsA total of 106 patients were included, 51 from Bogotá and 55 from Barranquilla. The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean population age was 35 years and 81% were females. Most of patients developed renal involvement during the first year of the disease, and 27% debuted with LN. More than 75% of the patients underwent renal biopsy, with the vast majority of cases presenting proliferative forms of LN, especially type IV. For all patients this was their first kidney biopsy. Anti-C1q positives were present in 60% of the patients, with a mean of 38μ/mL, and 70% presented positive anti-dsDNA antibodies. The mean adiponectin levels were above the normal value. Regarding the genetic variables, the alleles most frequently found were HLA DRB1*04 and HLA DQB1*03.

Characteristics of patients included.

| Demographic characteristics | n:106 | Histopathological characteristics | n:80 | Biomarkers | n:106 | Genetic characteristics n:106 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 35 | Kidney biopsy | Mean proteinuria (g/24h) | 1927 | HLA DRB | (%) | HLA DQB | (%) | |

| Sex | I (%) | 0 | Anti-dsDNA (%) | 70 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 21 | |

| Male (%) | 19 | II (%) | 1.5 | Anti-C1q (%) | 60 | 2 | 0.5 | 3 | 36 |

| Female (%) | 81 | III (%) | 9 | Mean adiponectina (μg/mL) | 16.9 | 3 | 17 | 4 | 9 |

| IV (%) | 77 | ANA (%) | 95 | 4 | 19 | 5 | 14 | ||

| Start year of LN | V (%) | 11 | Homogeneous (%) | 40 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 19 | |

| 1 year (%) | 65 | VI (%) | 1.5 | Speckled (%) | 57 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 0.5 |

| 2–5 years (%) | 31 | Mean activity index | 7 | Nucleolar (%) | 1 | 9 | 1.5 | 14 | 0.5 |

| 5–10 years (%) | 2 | Mean chronicity index | 3 | Cytoplasmic (%) | 1 | 10 | 2 | ||

| More than 10 years (%) | 2 | Peripheral (%) | 1 | 11 | 4 | ||||

| LN as debut (%) | 27 | Low complement (%) | 64 | 12 | 2 | ||||

| Mean SLEDAI | 16 | 13 | 8 | ||||||

| 14 | 2 | ||||||||

| 15 | 15 | ||||||||

| 16 | 4 | ||||||||

HLA II expression of the patients was compared with healthy controls and Colombian patients with SLE without LN. It was found that HLA DRB1*0301 was associated with SLE (OR 2.24, p=0.0275), and there was a tendency for the association between HLA DBR1*1501 and the risk of presenting SLE (OR 1.8, p: 0.06). In SLE patients, HLA DRB1*0404 and DRB1*1101 are protective factors for the presence of LN (OR 0.42, p=0.0030 and OR 0.49, p=0.046 respectively). In turn, HLA DRB1*0701 (OR 3.15, p=0.0452) and DRB1*0802 (OR 8.3, p=0.020) are susceptibility factors for the presence of LN. HLA DRB1*0802 to act as a risk factor for LN when compared to healthy controls (OR 2.24, p=0.0275). There was no association with HLA DQB* alleles.

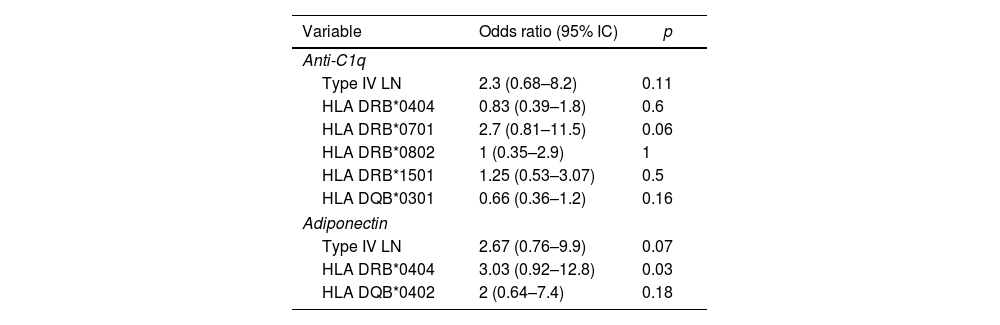

Anti-C1q associationsIt was found that the presence of positive anti-C1q titers was a possible association with the presence of type IV LN, however confidence intervals were not significant (OR 2.3 [95% CI: 0.68–8.2]). A similar case was presented with the possible association between anti-C1p positives and the presence of HLA DRB1*0701 (2.7 [95% CI: 0.81–11.5]) (Table 2). In turn, HLA DQB1*0301 seems to act as a protective factor for the presence of positive anti-C1q (OR 0.66 [95% CI: 0.36–1.2]). No possible association was found between anti-C1q and other allele variables of HLA DRB1 and HLA DQB1. In addition, when evaluating the possible association between anti-C1q and high levels of adiponectin, it was not found. There was also no significant association between anti-C1q with any demographic variable, presence of anti-dsDNA, hypocomplementemia, extractable nuclear antibodies, or proteinuria levels.

Associations of anti-C1q positive or elevated levels of adiponectin.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% IC) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-C1q | ||

| Type IV LN | 2.3 (0.68–8.2) | 0.11 |

| HLA DRB*0404 | 0.83 (0.39–1.8) | 0.6 |

| HLA DRB*0701 | 2.7 (0.81–11.5) | 0.06 |

| HLA DRB*0802 | 1 (0.35–2.9) | 1 |

| HLA DRB*1501 | 1.25 (0.53–3.07) | 0.5 |

| HLA DQB*0301 | 0.66 (0.36–1.2) | 0.16 |

| Adiponectin | ||

| Type IV LN | 2.67 (0.76–9.9) | 0.07 |

| HLA DRB*0404 | 3.03 (0.92–12.8) | 0.03 |

| HLA DQB*0402 | 2 (0.64–7.4) | 0.18 |

It was found that high levels of adiponectin could behave as a risk factor for the presence type IV LN, however, no clear association was found (OR: 2.67 [95% CI: 0.76–9.9]) (Table 2). No association was found between high levels of adiponectin and the presence of other positive antibodies, proteinuria levels or demographic variables of the population studied. On the other hand, although high adiponectin levels seem to be associated with the presence of HLA DRB1*0404 and HLA DQB1*0402, no significant association was found (OR 3.03 [95% CI: 0.92–12.8] and OR 2 [95% CI: 0.64–7.4] respectively). No association with other alleles of HLA DRB or HLA DQB was found.

CorrelationsThere was a positive correlation between the high anti-C1q values and the activity index of the renal biopsy (r: 0.21, p 0.07). On the other hand, the presence of high adiponectin levels correlated negatively with complement values (r: −0.29, p: 0.007). No correlation was found between levels of anti-C1q or adiponectin with other clinical, paraclinical or histological variables.

DiscussionC1q is the first component of the complement cascade, contains six globular domains and a single region called like-collagen and plays an important role in cleaning immune complexes. It binds to Fc portion of immune complexes and participates in the clearance of apoptotic cells; the most frequent isotype is IgG and the technique used for its identification is ELISA.8,9 C1q deficiency is a risk factor for developing lupus-like syndromes or glomerulonephritis.10,11 Anti-C1q are present in 4% of healthy people in the fifth decade of life, and 18% in the eighth decade of life.9,12 In addition, they are found between 20% and 44% of patients with SLE,13–15 and they are correlated with SLE activity.16 Adipokines also participate in the regulation of the immune system,17 being elevated in patients with autoimmune diseases compared with healthy individuals.18 Due to its known role as modulators of inflammatory processes in different population groups, elevated levels of adipokines could be useful to identify renal involvement in SLE.19 This study aimed to establish whether there is an association between the presence of anti-C1q and high levels of adiponectin with LN and the expression of HLA II genes in the Latin-American population. The possible association of biomarkers with different clinical and paraclinical variables was evaluated, later on the evaluation of their association with the different allelic variables was sought.

The demographic characteristics of this cohort was similar to that reported in previous cohorts.15,20–26 The availability of renal biopsy of our cohort was higher compared to other studies, especially in Latin America.24–26 With an elevated percentage of patients with proliferative LN (III-IV), similar to the one reported by Gomez-Puerta et al.26 The number of patients with high anti-C1q was 60%, similar to reported in previous studies,20,27,28 except in some studies of Asian population that has been reported in up to 85% of LN patients.21

In our study, we found a possible association between the presence of anti-C1q and type IV LN, statistical significance was not achieved, probably due to the sample size. Moroni et al. reported similar findings in two previous studies, where they found that anti-C1q seems to be the best predictor of LN appearance in proliferative forms.28,29 This result contrasts with that reported by Marto et al., where although higher titers of anti-C1q were found in active LN patients, there was no higher prevalence of anti-C1q in patients with active LN compared with quiescent.27 Previous studies reported an association between positives levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies to the presence of anti-C1q, the sensitivity and specificity of both biomarkers increases the detection of renal exacerbations.5,30,31 Strikingly, in our study we didn’t find this association. However, a similar number of patients had positive anti-C1q and anti-dsDNA antibodies (70% and 60%, respectively), as well as hypocomplementemia that occurred in 64% of patients. We consider that this association was not found due to the design of the study.

In turn, there was a positive correlation between the levels of anti-C1q and the index of activity in the renal biopsy, similar to that reported by Moroni et al.29 Thus suggesting that not only is the presence of these antibodies important, but high values of them may be associated with greater severity of the LN, which would require to be specially attentive for an early intervention on the disease.

We found HLA DRB1*04, DRB1*03, DRB1*15 are frequent allelic variables in Colombian patients with LN, however no specific association was found to any type of LN. A recent meta-analysis found HLA DRB1*15 and DRB1*03 as risk factors for LN and HLA DRB1*04 and HLA DRB1*11 as protective factors.32 In other populations the expression of HLA DRB1*15 corresponds to a constant risk factor for the development of LN33–35; however, in our population, despite the fact that it appears as a risk factor for the development of SLE, it does not seem to be for LN. Moreover, HLA DRB1*04 and HLA DRB1*11 are protective factors for presence of LN, findings similar to those reported in other studies.32

As expected, in our study there was possible association between the presence of anti-C1q and HLA DRB1*0701, although this did not reach statistical significance probably due to the current sample size. Furthermore, the presence of HLA DQB1*0301 seems to act as a protective factor for the expression of anti-C1q, which opens a possible protective role for the development of LN in the proliferative forms. It was not possible to establish specific associations with expression of HLA DRB1*1501 or DRB1*03, which increases the probability that this allelic variable does not confer risk to develop LN in the Latin-American population. Further studies are required to corroborate this finding.

In our study, elevated adiponectin levels seems to act as risk factor with type IV LN, similar to anti-C1q. Rovin et al. found that adiponectin levels in plasma and urine were higher in patients with LN than in patients with SLE without LN and healthy controls.36 In addition, it was found that adiponectin levels were higher in patients with inflammatory LN (III–IV), compared with non-inflammatory, being unable to establish an statistical association.36 Diaz-Rizo et al. also reported elevated levels of serum adiponectin in patients with LN. Finding that is associated with the presence of proteinuria in SLE.37 In our study, this association was not found, similar to those reported by de Souza et al.38

High levels of adiponectin had an inverse correlation with complement levels. We did not find a correlation between adiponectin and proteinuria levels, in contrast to reports in previous studies.36,37 There is also growing evidence for the role of adiponectin in urine as a marker of renal exacerbation in SLE,36,39 however no determination of adiponectin in urine was made in this study.

A possible association of high levels of adiponectin with the expression of HLA DRB1*0404 and HLA DQB1*0402 was found, which is unanticipated, taking into account that as previously mentioned in the Colombian population, HLA DRB1*0404 seems to be a protective factor for the development of LN. It was not possible to establish association between high levels of adiponectin and other allelic variables, including HLA DRB1*1501. Such finding, as previously mentioned, suggests that in Latin-American patients this allelic variable behaves differently than in the rest of the world.

This is, to our knowledge, the first Latin-American study that seeks to establish the possible association between anti-C1q and adiponectin and the presence of HLA genes DRB1 and DQB1. In addition, it corresponds to the cohort with the largest number of patients with LN reported in Latin America, and one of the largest reported worldwide. Being a multicentric study confers a better external validity. It provides important information to establish the bases for subsequent studies with long-term follow-up with periodic determination of different biomarkers in order to establish their possible role as predictors for the appearance of LN, since studies to date have limited sample size, their conclusions should be taken with caution.5

On the other hand, this study has some limitations. Although HLA determination was performed in a control group of healthy patients and patients with SLE without LN, anti-C1q and adiponectin levels were not measured in these groups. This fact limits the scope of the study and its ability to find certain associations. The sample size limited the power of the study to reach statistical significance in the associations considered. The design of the study does not allow to establish the predictive value of biomarkers in the development of LN. The determination of other postulated biomarkers possibly associated with LN was not performed, as neither was the measurement of adiponectin in urine. Because in our study the majority of patients presented type IV LN, the interpretability of the results and the ability to determine associations with other types of LN are limited.

ConclusionsIn Colombian population, there is a tendency for the association between the presence of anti-C1q and high levels of adiponectin with LN proliferative forms. In addition, the expression of HLA II genes, known as risk factors for LN, was not associated with the expression of anti-C1q, adiponectin or some specific type of LN.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the National University of Colombia. All the participants accepted to sign freely and voluntarily the informed consent according to the declaration of Helsinki.

FundingFunding was received through a research grant given by Research and Extension Programs Office of the National University of Colombia, Bogotá. Additional Funding was given by Immunology and Molecular Biology Research Group ot the Universidad del Norte.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

To Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, Clínica de la Costa, and Clínica Carlos Lleras for your contribution in collecting the patients.