Articular involvement in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is well recognized as one of the most common manifestations of the disease. This article reviews the recent knowledge of the clinical manifestations, diagnostic techniques and therapies used for the treatment of joint involvement in SLE. The degree of articular involvement is characterized by widespread heterogeneity in terms of clinical presentation and severity. It may range from minor arthralgia without erosions or deformity to erosive arthropathy and severe functional disability. Inflammatory musculoskeletal manifestations are described as a major cause of pain impacting daily activities and as a major determinant of quality-of-life impairment. Thus, physicians must be aware of articular involvement in SLE. Lupus arthritis diagnosis may be challenging, due to the frequently mild synovitis. The introduction of new more sensitive imaging techniques, such as ultrasound, and MRI have contributed significantly to improving the diagnosis of osteoarticular involvement in SLE. There are several treatment options for the management of joint manifestations in patients with SLE. The choice of treatment will depend on the type and pattern of joint involvement, its severity, and the characteristics of the patient.

El compromiso articular en lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) es bien reconocido como una de las manifestaciones más comunes de la enfermedad. En el presente artículo se revisa la evidencia reciente sobre las manifestaciones clínicas, las técnicas de diagnóstico y los tratamientos utilizados para tratar el compromiso articular en el LES. El grado de compromiso articular se caracteriza por la amplia heterogeneidad en su presentación clínica y su gravedad. Puede variar desde artralgia leve sin erosiones o deformidad, hasta una artropatía erosiva y discapacidad funcional. Se describen las manifestaciones inflamatorias musculoesqueléticas como la principal causa de dolor que afecta las actividades de la vida cotidiana y como uno de los principales factores determinantes del deterioro de la calidad de vida. Por lo tanto, los médicos deben estar conscientes del compromiso articular en LES. El diagnóstico de la artritis lúpica puede ser difícil debido a la sinovitis, usualmente leve. El advenimiento de nuevas técnicas de imágenes más sensibles, como la ecografía y la resonancia magnética, ha contribuido significativamente a mejorar el diagnóstico del compromiso osteoarticular en LES. Existen varias opciones de tratamiento para las manifestaciones articulares en pacientes con LES. La opción de tratamiento dependerá del tipo y del patrón del compromiso articular, así como de las características del paciente.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease affecting different organs and systems. In its original description in 1872, Kaposi reported joint involvement in 53–95% of SLE patients.1 After that, articular involvement in lupus was generally thought to be of secondary importance until 1940.2–4 A review conducted by Slocumb from the Mayo Clinic included joint involvement as part of the systemic compromise of SLE.5 Articular involvement was definitively established as a diagnostic feature of SLE in 1950 following the publication by Daugherty and Baggenstoss.6

The relevance of SLE joint involvement led to its inclusion in the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria, proposed in 1982.7 Nowadays, articular involvement in SLE is well recognized as one of the most common manifestations of the disease.8–13 Despite it is not life-threatening, articular involvement is the most common and the earliest manifestation of SLE and significantly affects the quality of life of these patients.14

This article reviews the recent knowledge of the clinical manifestations, diagnostic techniques and treatments used to manage the joint involvement in SLE.

MethodsLiterature searchThe bibliographic search was conducted in the MEDLINE database up to September 2020. Publications were identified using the following MeSH terms: “Systemic Lupus Erythematosus” and [“arthritis” or “arthralgia” or “joint”].

Inclusion criteriaOriginal articles that described articular manifestations of SLE, the impact of prognosis and quality of life, diagnostic techniques, and treatment were included. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- •

Type of studies: Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized clinical trials, reviews, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and cross-sectional studies.

- •

Population: Patients older than 18 years old with SLE and articular involvement.

- •

Intervention: Studies describing the articular patterns, diagnostic techniques, prognosis, treatment, and complications.

- •

Articles without access to the full text.

- •

Case reports.

- •

Studies that were not conducted in humans.

Title and abstract screening was conducted to identify potentially relevant articles of interest, followed by full-text analysis. Data were extracted from full-text articles that met de inclusion criteria.

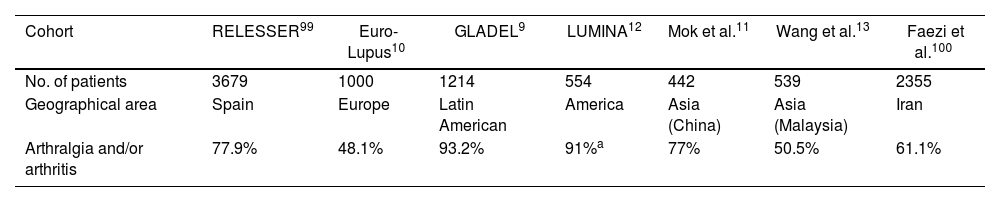

ResultsClinical manifestationsMore than ninety percent of patients with SLE experience joint symptoms during their clinical follow-up and it is the clinical form of presentation in almost 50% of patients.14,15 The degree of articular involvement is characterized by a wide heterogeneity in terms of clinical presentation and severity.14 It may range from mild arthralgia without erosions or deformity to erosive arthropathy and severe functional disability. Table 1 shows the prevalence of joint involvement in different cohorts of lupus patients representing different geographic areas.

Prevalence of joint involvement in a cohort of SLE patients representing different geographic areas.

Arthralgia represents one of the most frequent symptoms of SLE, manifesting as persistent joint pain, transient or migratory, but without evidence of swelling. It involves mostly the hands and sometimes could be associated with morning stiffness.14

A high percentage of SLE patients have arthritis.16 It can affect large and small joints. SLE-associated arthritis is usually transient, migratory, reversible, and non-erosive.17 The most affected joints are the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), wrists and knees.18 Foot involvement includes hallux valgus, subluxation of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints and increased plantar arch. On some occasions, atypical joints such as the temporomandibular and sacroiliac joints (particularly in men) can be affected.19 The joint involvement may present initially at the clinical onset of SLE or at any time during the course of the disease. The patient's symptoms (e.g., inflammatory pain and morning stiffness) are usually more prominent than the synovitis on physical examination, which is usually mild. In most patients, this inflammatory process is not associated with bone erosions and deformity development,20 but the use of more sensitive techniques such as ultrasound imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown the presence of bone erosions in SLE patients.

SLE patients can also experience a more severe arthropathy, leading to joint deformities. Arthritis mutilans is a rare complication in SLE, which is characterized by sclerosis of the terminal part of the distal phalanges (i.e., acro-osteolysis) and is often associated with Raynaud's phenomenon. Sometimes, trophic tracts of the skin of the fingers and nails are present.21

Jaccoud's arthropathy (JA)In 1867, François-Sigismond Jaccoud first described deforming, non-erosive, reversible arthropathy associated with rheumatic fever in a young patient.22 In 1962, Zvaifler described the characteristics of flexion contracture and ulnar deviation of the MCP joints in lupus.23 Later, Bywaters referred to Zvaifler's description as “Jaccoud's arthropathy” because of its similarity to the deformities described in 1867 following rheumatic fever.24

These deformities consist of reducible MCP joint dislocation, deviation, and occasional hyperextension of the interphalangeal (IP) joints of the thumb.8 JA corresponds to a form of deforming arthropathy proposed by Vugt et al. and is characterized by chronic non-erosive deformities.25 JA has been described in SLE patients24,26 with a prevalence of up to 42%.18,27 This arthropathy was also observed in other autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic sclerosis, Sjögren's syndrome, polymyositis and vasculitis), as well as infections, and neoplasms.28

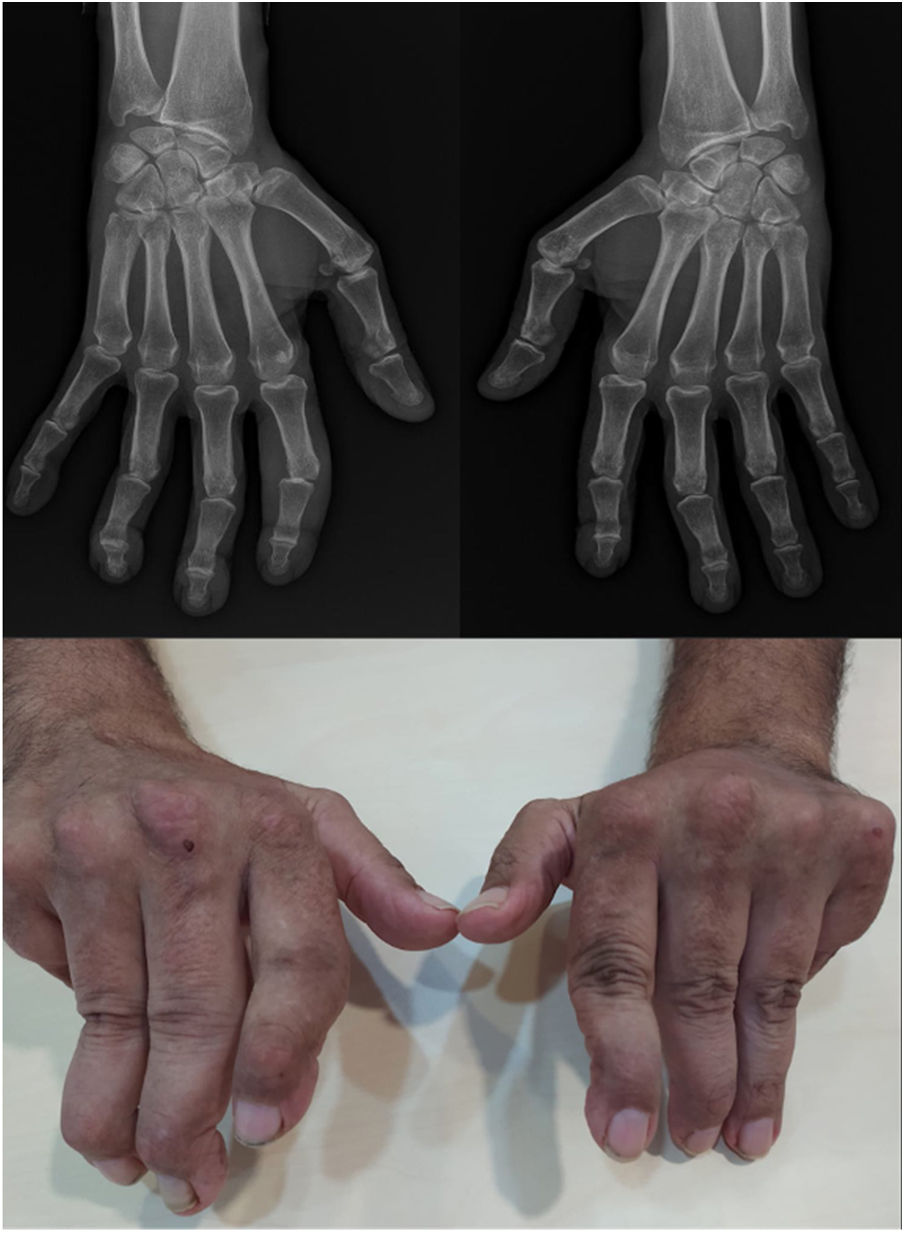

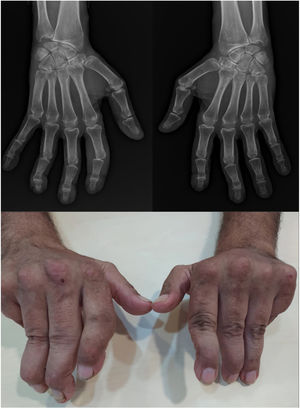

Joint deformities in JA may be limited to ulnar deviation of the MCP joints. JA may be widespread and can simulate evolved rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with lateral hyperlaxity of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, swan neck deformities, boutonniere deformities, Z-shaped thumb, and carpal hyperlaxity29 (Fig. 1).

Jaccoud-type arthropathy. 40-Year-old male patient with long-standing systemic lupus erythematosus (positive ANA, anti-dsDNA, and anti-nucleosome antibodies) and triple positive antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies were negative. Hand deformities including ulnar drift at the metacarpophalangeal joints, swan neck and boutonnier deformities, and hyperextension of the interphalangeal joint of the thumb closely resemble those seen in rheumatoid arthritis. The absence of erosions on radiographs and their reducibility differentiates this condition from deforming arthritis of rheumatoid arthritis.

Recently, a new set of classification criteria for JA has been proposed.30 These criteria are intended to define the presence of Jaccoud-type lupus arthropathy (JLA) to differentiate it from Jaccoud-type deformities seen in RA, and other conditions, as well as ‘primary’ and ‘familial’ forms of arthropathy. JLA may be of two types: ‘classical’, when the deformities are ‘reducible’ by passive movement and ‘severe’, when the deformities are fixed.

The presence of JA in patients with SLE has been associated with certain HLA haplotypes (e.g., HLA-A11 and HLA-B61), older age, late-onset of the disease, polyautoimmunity (i.e., presence of more than one autoimmune disease in a single patient) with Sjögren's syndrome, and frequent tendon rupture.31,32

RhupusOverlap syndromes can be defined as multiple disease states occurring together to produce a unique clinical phenotype and disease behavior. The concomitant presence of two autoimmune diseases – SLE and RA – in the same patient is known as rhupus. The first reports of the coexistence of SLE and RA date back to 1963 by Toone, who described the presence of lupus erythematosus cells in the serum of 15 patients with RA. In the following years, case reports of SLE patients with RA-like arthritis and RA patients presenting with systemic manifestations of SLE were reported. But it was not until the 1970s when the term rhupus was first described by Peter Schur.33 He defined rhupus as a rare clinical condition in which patients show signs and symptoms characteristic of both autoimmune diseases (RA and SLE).

There is no official definition for rhupus. The most frequently accepted definition of rhupus is fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for both SLE and RA. However, some authors included as rhupus only patients with erosions, rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP) and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody. Although polyautoimmunity is a common phenomenon described in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases, only a relatively small series of patients has been described as rhupus so far.

The true prevalence of this overlap condition seems to be low (0.01–2%) (34,35). It is essentially a sequential disease in which RA and SLE features are rarely diagnosed simultaneously. RA is the first diagnosis in two-thirds of patients.36,37

Patients diagnosed with rhupus undergo a particular clinical course. Studies of rhupus patients show predominant signs and symptoms of RA over organic damage associated with SLE.18 Erosive arthropathy is the predominant feature in which the bone structural damage appears to resemble more to RA, with a higher frequency of bone erosions and synovial hypertrophy than in SLE.38,39 Nevertheless, patients can present any classic SLE manifestations. The prognosis of rhupus syndrome typically depends on the severity of the organ damage, and there is high-risk subset of patients with a worse long-term prognosis.40

Other overlap syndromesMixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) was first described in 1972 as an entity with mixed features of SLE, systemic sclerosis, polymyositis/dermatomyositis and RA.41 High titers of antibodies targeting the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle (U1 U1-RNP) in peripheral blood are a sine qua non for the diagnosis of MCTD.42 Joint involvement varies from minimal arthralgias, arthritis of the small or large joints and erosions typical of RA to arthritis mutilans. In general, polyarthralgia is an early and common symptom in MCTD, occurs in approximately 60% of patients and may be accompanied by joint deformities with radiographic changes.41 Arthritis is included in all the criteria sets of MCTD, being polyarthritis, the most common pattern described.42 RF and anti-CCP may be positive.43

Other articular manifestationsSubcutaneous nodules like RA nodules are rarely found in SLE, and are usually present in the olecranon, MCP and PIP joints. The histopathological characteristics are like those found in RA patients.44 Tenosynovitis may be an early manifestation, and tendon rupture can occur. Between 10 and 13% of patients present tenosynovitis including epicondylitis, rotator cuff tendinitis, Achilles tendinitis, posterior tibial tendinitis, and plantar fasciitis.45

Damage accrual and prognosisSLE Damage is primarily assessed using the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC)/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Damage Index (SDI),46 which has been extensively validated. SDI items represent irreversible damage that has occurred after the diagnosis of SLE and predicts future mortality and is highly associated with both overall physical health and the physical function measured by the patient-reported outcome measurement short-form 36 Health Survey (SF-36).47,48 Deforming or erosive arthritis is included under the musculoskeletal system subheading.

Inflammatory musculoskeletal manifestation is described as a major cause of pain. Joint pain, with or without arthritis, worsens the quality of life (HRQOL) in compromised patients, interferes with daily activities in 73% of SLE patients, and results in low productivity or work disability in 49% and 17% of these patients, respectively.49 It has been established that disease activity in the musculoskeletal system is a major determinant of HRQOL impairment in SLE.50,51

DiagnosisDiagnosis of lupus arthritis may be challenging because of a frequently mild synovitis. Clinicians should be aware of making a diagnosis solely based on patient history when objective synovitis is not found at clinical examination.

BiomarkersAround forty-five percent of patients with SLE are RF positive, usually at low titer, and no relationship has been found with the presence of erosive arthritis.14,52 It was first suggested in 2001 that anti-CCP could be a useful marker to discriminate patients with erosive disease in SLE.53 The presence of anti-CCP may account for an 18–20-fold increased risk of developing erosive arthritis in patients with SLE,54–56 supporting the idea that anti-CCP could be a predictor of erosive disease in patients with SLE.

Some authors have pointed out an association of JA with several biomarkers. However, many of these associations have not shown consistent results in different series. These laboratory markers include the presence of RF,57 higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) or Interleukin-6, increased anti-dsDNA,27 antiphospholipid antibodies (either lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies),25 and anti-U1-RNP antibodies.58 More recently, a significant association of anti-carbamylated proteins has been described in patients with SLE and joint involvement, compared with patients without joint involvement.59

Among rhupus patients, a clear difference between the positivity of the RA antibodies (anti-CCP and RF) in comparison with SLE has been described,35 supporting the idea that rhupus is a true overlap. No difference in the prevalence of anti-U1-RNP and other ENAs has been found between rhupus and SLE patients.34 Anti-U1-RNP occurrence in patients with lupus clinical features may be indicative of diagnostic issues. The presence of anti-U1-RNP antibodies in patients that meet the SLE criteria (but not the MCTD critreria) was associated with manifestations such as Raynaud phenomenon, musculoskeletal and lung impairment, some clinical features frequently encountered in MCTD patients and only rarely described in lupus populations.60

ImagingClassically, a non-erosive inflammatory joint pattern has been described, but the advent of new more sensitive imaging techniques, such as MRI, and ultrasound (US) and even the use of the Power Doppler modality, have significantly contributed to improving the diagnosis of osteoarticular involvement in SLE.61

X-rayIn patients with lupus arthritis, plain radiographs may demonstrate soft tissue swelling of the involved joints. The presence of acral sclerosis, soft tissue calcification, periarticular osteoporosis, and cystic bone lesions has been widely described in SLE patients.14 Carpal instability may be seen in 15% of patients, characterized by an increase in the inter-articular space between the scaphoid and the lunate or other carpal bones. Wrist instability is demonstrated by radiographs performed with a radio-ulnar deviation of the wrist.61

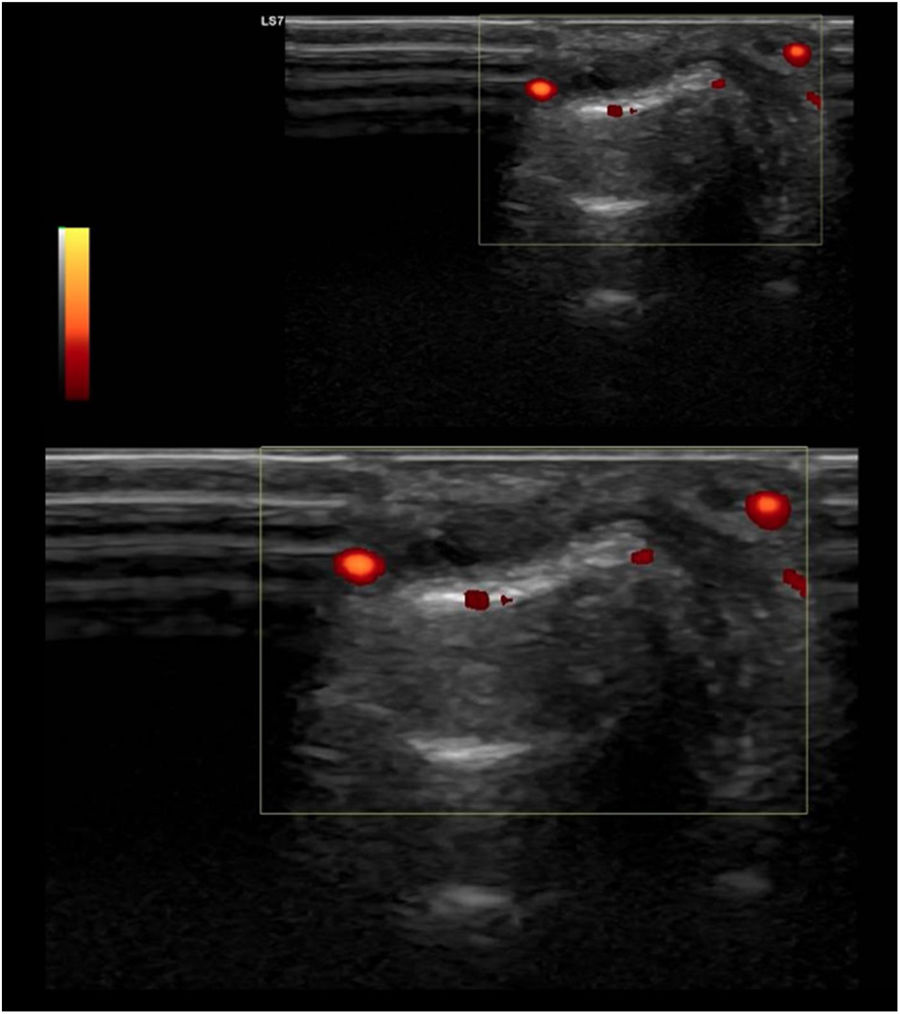

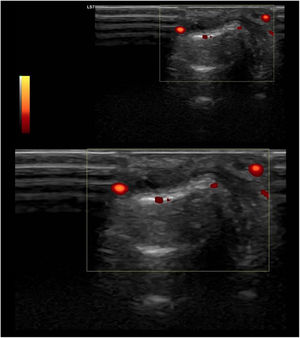

UltrasoundUS today is probably the most productive and cost-effective method for detecting synovitis in SLE. It is widely accepted that musculoskeletal ultrasound detects a higher number of swollen joints and tendons than the clinical physical examination in inflammatory arthropathies. US has shown different results in terms of sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of SLE (synovitis 25–94%, Power Doppler positivity 5–82%, tenosynovitis 28–65%, erosions 2–41%)62–68 (Fig. 2).

Standard ultrasound study with integration of a power Doppler module using a linear probe in a patient with SLE. Longitudinal examination at the level of the proximal interphalangeal joint indicates the presence of a discrete component of synovial effusion, irregularity and prominence of the articular component of the distal epiphysis of the proximal phalanx. The Power Doppler evaluation showed a moderate increase in vascular uptake at the joint level of synovial capsular distention and periarticular soft tissues in the distal epiphysis of the proximal phalanx. Findings suggestive of active synovitis with associated joint remodeling and active inflammatory and neovascular signs of the periarticular soft tissues.

Even though sometimes patients with SLE only report hand arthralgia without arthritis, subclinical synovitis can reach 38% in some series.65 The role of US in this area is essential for the early diagnosis of lupus. Furthermore, a prospective study with 6 years of follow-up69 showed that patients with arthralgia who had baseline US alterations had worse osteomuscular outcomes and prognosis and received more immunosuppressive therapy at the end of the follow-up. This finding highlights the possible predictive role of joint US.

It should also be noted that both US and MRI identify erosions in patients with SLE (excluding rhupus and other overlaps). Although there are studies that object that patients with SLE and erosions did not score worse on the HRQOL, further studies are needed to determine whether these erosions lead to accumulated irreversible joint damage in the long term in these patients. Another point to be highlighted is that the current use of US has enabled us to determine that tenosynovitis of the extensor carpal tendons is more prevalent than arthritis of the carpus or the MCP joints, as evidenced in numerous series.63,66,67

Finally, there are different studies that relate US alterations with SLE activity. Some examples include the study by Torrente-Segarra et al.64 where a significant relationship was found between the US alterations of the patients and the SLEDAI, or the study by Gabba et al.63 which found a significant relationship between power Doppler and the musculoskeletal domain of the BILAG.

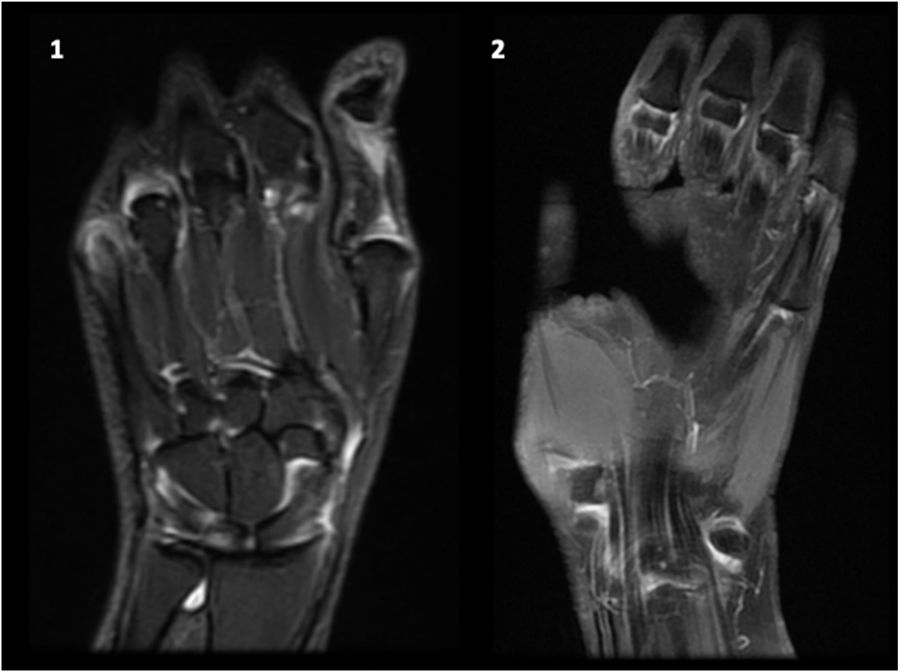

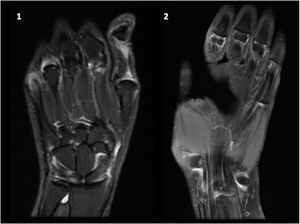

Magnetic resonance imagingThe emergence of more sensitive imaging techniques, such as MRI, allows an early identification of joint involvement in patients with SLE including synovitis, erosions, bone edema and tenosynovitis.

Following similar principles developed by the OMERACT group for scoring system (RAMSIS),73 a systematic evaluation of the hands and wrists is also suggested for SLE patients.20,38,70,71

According to the RAMRIS criteria, MRI evaluation in SLE includes:

- 1.

Wrist: distal radioulnar joint, radiocarpal joint, intercarpal–carpometacarpal joints and proximal metacarpal epiphyses.

- 2.

Hand: Second–5th metacarpophalangeal joints, considering distal metacarpal head and proximal phalangeal base.

- A)

Synovitis: the scale is 0–3 where 0 is normal, 1–3 (mild, moderate, severe) are by thirds of the presumed maximum volume of enhancing tissue in the synovial compartment.

- B)

Erosions score in the range 0–10, with 10% increments based on the proportion of eroded bone.

- C)

Bone marrow edema scores in the range 0–3 according to the proportion of bone with edema (in increments of 33%).

- A)

Gadolinium enhanced-MRI showed to be the most sensitive imaging modality to study inflammatory joint involvement, including synovitis, erosions (particularly in wrist joints), bone edema and surrounding soft tissue. MRI also improved the accuracy of quantitative measurement of inflammatory joint burden, as well as our understanding of the pathogenesis of inflammatory joint disease and repair.72,73

MRI showed erosions in up to 98% of patients with SLE, particularly in the wrists; although wrist erosions have also been shown in healthy subjects, the prevalence is significantly higher in SLE patients as compared with to healthy controls (up to 47%), even after adjusting for age.71 The most affected areas are the distal side of the second and third MCP joints (phalangeal basis).38 When compared to RA, the second MCP joint is the only area where the prevalence of erosions is significantly higher than in SLE patients.20

Data show that erosive lupus arthritis can be independent of RF and anti-CCP status, but a small number of patients studied who were anti-CCP positive showed a higher burden of erosive disease.20 Regarding bone edema it can affect up to 35–55% of patients with SLE, with a higher frequency in the wrist joints, while it is 0% in healthy individuals.71 Synovitis can be present in up to 100% of SLE patients who complain of hand inflammatory pain of the wrists and hands.20,70 Tenosynovitis in SLE affected patients has been poorly evaluated using MRI. The tenosynovitis score system,74 has reported 20% and 10% evidence of tenosynovitis of the extensor and flexor tendons, respectively,20 though is smaller cohorts it has reached up to 85%.75

These new tools are just beginning to be used in SLE, both due to novelty and cost limitations. All these findings suggest the presence of subclinical inflammatory joint involvement, which could increase damage accrual over time, introducing different therapeutic strategies and maybe more intensive medical care; however, the actual correlation between function and clinical significance has not yet been studied (Fig. 3).

Synovial fluidSynovial fluid is usually mildly inflammatory (between 2000 and 15,000cells), predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate, with normal glucose concentrations, normal or increased proteins, and normal or decreased complement concentrations. In joint fluid, ANAs can be positive with low titers, and lupus erythematosus cells can also be identified. The biochemical analysis of the synovial fluid does not differ from other inflammatory arthropathies, including RA or psoriatic arthritis.19,76

Synovial analysis has identified unique pathophysiological mechanisms in SLE arthritis, suggesting that it is distinct from RA. The synovial biopsy in SLE arthritis has shown a unique molecular signature, with upregulation of interferon-inducible genes while genes involved in extracellular matrix homeostasis are down-regulated. In contrast, in RA synovial tissue genes involved in T cell and B cell regulation are up-regulated.77

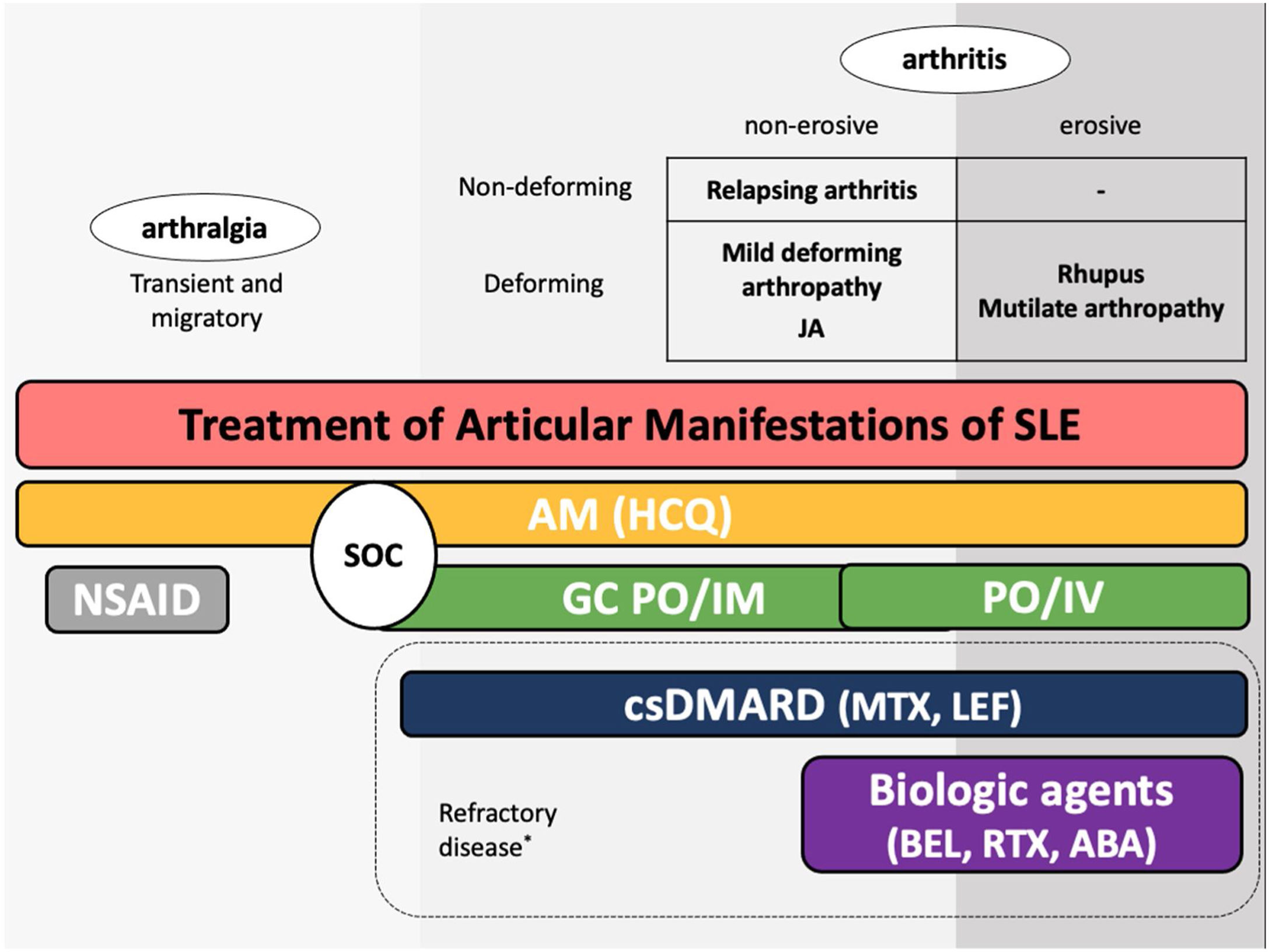

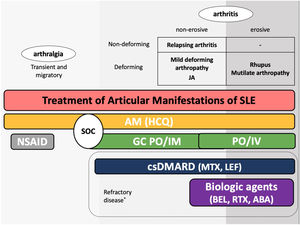

TreatmentThere are several treatment options for the management of joint manifestations in patients with SLE. The therapeutic armamentarium currently available includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antimalarial, glucocorticoids, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs, e.g., methotrexate, MTX), and targeted therapies including B lymphocyte stimulator protein (BLyS)-specific inhibitor (belimumab), anti-CD20 (rituximab) and a costimulatory inhibitor (abatacept).78 The choice of treatment will depend on the type and pattern of joint involvement, its severity, and the characteristics of the patient.

Given the broad spectrum of beneficial effects and the safety profile, antimalarial drugs are recommended for all patients with SLE during the whole course of the disease, except for patients who reject treatment or have absolute contraindications to take them.79 Hydroxychloroquine should be administered to most SLE patients, regardless of the severity of the disease and should not be discontinued during pregnancy.80

Low-dose glucocorticoids (≤10mg/day of prednisone equivalent) are usually administered, and if high doses are needed, corticoid-sparing agents should be used. Direct injection of corticosteroids into joints can be useful in certain cases.81 NSAIDs could be used as adjunct therapy during any stage of treatment for non-erosive, nondeforming inflammatory polyarthritis.29 However, the current trend is to use low-dose glucocorticoids instead of NSAIDs. The EULAR guidelines recommend hydroxychloroquine or low-dose glucocorticoids for patients without major organ lesions but with symptoms such as arthritis, muscle pain, and fever.82

MTX is the csDMARD with more evidence in the treatment of musculoskeletal involvement in SLE.83 Some studies, including randomized, controlled double-blind and open-label trials suggested that MTX (10–20mg/week) is effective in controlling articular activity of SLE and resulted in prednisone dose reduction.81 Other immunosuppressants used are leflunomide, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, but their evidence in the literature is limited.81

Literature data suggest that belimumab may potentially be used in the treatment of severe joint symptoms in glucocorticoid-resistant lupus or in patients refractory to conventional treatment. According to pivotal studies, arthritis is one of the lupus manifestations most likely to respond to belimumab.84 Additionally, polyarthritis, high disease activity (SLEDAI≥10), and increased anti-dsDNA have been suggested as predictors of response to belimumab.85 Targeting CD20 with rituximab has been endorsed in several centers where it is used as an off-label therapeutic option in SLE, mostly for refractory renal disease, but also for other organ manifestations when conventional treatment has failed, including severe lupus polyarthritis.86,87

Literature data suggests the efficacy of abatacept to treat SLE patients with joint involvement.14 A multicenter exploratory phase II clinical trial involving 175 patients with non-life-threatening SLE evaluated abatacept efficacy. The proportion of new BILAG A/B flares over 12 months was 79.7% in the abatacept group and 82.5% in the placebo group. Although the primary/secondary endpoints were not met in this study, improvements in certain exploratory measures suggest some abatacept efficacy in patients with SLE.88 Therefore, new clinical trials on abatacept should be designed to further confirm its potential use in SLE.89 The use of TNF inhibitors in SLE has also been reported. However, this approach is not routine in SLE partly because of the risk of developing drug-induced lupus. Some success cases have been reported in renal lupus patients as well as in patients with ‘hard-to-treat’ joint disease and other manifestations.90

The guidelines for the treatment of SLE submitted by the Latin American Group for the Study of Lupus (GLADEL, Grupo Latino Americano de Estudio del Lupus)-Pan-American League of Associations of Rheumatology (PANLAR) suggested the use of glucocorticoids and antimalarials as the standard of care (SOC).79 If the disease remains active after SOC, adding either MTX, leflunomide, belimumab or abatacept besides other immunosuppressants should be considered. A significant proportion of patients will achieve adequate symptom control with SOC and could be spared the adverse effects/excess costs associated with those other options (Fig. 4).

Treatment of articular manifestations of SLE. The recommendations for management of articular manifestations of SLE are based on EULAR and GLADEL/PANLAR guidelines.79,82 The choice of treatment depends on the type of articular condition (arthralgia vs arthritis), its severity (activity and erosive phenotype), and the characteristics of each patient. AM: antimalarials; BEL: belimumab; csDMARDs: conventional synthetic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs; GC: glucocorticoids; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; JA: Jaccoud's arthropathy; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; MTX: Methotrexate; SOC: standard of care; RTX: rituximab. *Other potential treatments for refractory disease: Anifrolumab and Baricitinib.

With regards to treatment for rhupus syndrome, there is little data available based on a few case studies and small series.91 Erosive progression of rhupus can result in severe disability. For this reason, affected patients are treated with csDMARDs, mainly MTX. However, some rhupus patients have shown inadequate responses. There are some studies on biological treatments in patients with rhupus, where rituximab and abatacept appear to be more promising options of treatment.92–94 An observational study in refractory rhupus patients showed that anti-TNF-alpha agents may also reduce disease activity and protect against the progression of structural damage.95

A post hoc analysis of the MUSE trial (phase IIb) compared anifrolumab (an anti-type I interferon receptor monoclonal antibody) against placebo at week 52 on rash and arthritis measures with different stringency in patients with moderate to severe SLE. This study shows that anifrolumab treatment was associated with improvements versus placebo in specific SLE features, including arthritis evaluated using SLEDAI-2K, BILAG and swollen and tender joint counts.96

A phase IIb clinical trial with baricitinib, a low-molecular-weight compound targeting Janus kinase 1/2, in patients with SLE revealed that baricitinib was significantly more effective for relieving arthritis and skin manifestations than placebo and the trial met the primary endpoint (resolution of SLEDAI-2000 arthritis or skin manifestations at week 24).97 New biologics and small molecule drugs for SLE are under development.98

ConclusionsArticular involvement is one of the most common manifestations of SLE, and on many occasions is the first manifestation of the disease. Physicians must be aware that articular involvement in SLE greatly affects the perceived HQoL and therefore should not be underestimated. Joint involvement could influence daily activities and affect the quality of life. Recent advances in imaging, with the introduction of new more sensitive imaging techniques have significantly contributed to improving the diagnosis of osteoarticular involvement in SLE. Joint US in SLE is a very safe and inexpensive technique, which can help in early diagnosis of joint involvement in SLE, even in the absence of inflammation during the physical examination and it can contribute to the early diagnosis of the disease itself. MRI detects characteristic signs of bony alterations; however, currently there is no specific validated pattern of articular involvement associated with this disease yet available, though some studies are underway. The choice of treatment will depend on the type and pattern of joint involvement, its severity, and the characteristics of the patient. Glucocorticoids and antimalarials are the standard of care for articular involvement. Refractory manifestations require treatment with immunosuppressants or biologics.

- •

Articular involvement is one of the most common clinical manifestations in SLE.

- •

Refractory articular manifestations impact patients’ quality of life.

- •

Based on US and MRI studies new approaches for classification are needed.

- •

Refractory arthritis requires treatment with immunosuppressants and biologics.

José A. Gómez-Puerta received speaker honoraria from BMS, GSK, Roche and Lilly.

Beatriz Frade-Sosa received speaker allowance from Abbvie.

Tarek C. Salman-Monte received speaker honoraria from GSK.