The criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) classification (ACR/EULAR 2016), include labial salivary gland (LSG) biopsy using the focus score (FS). But, in some cases it continues to be based on Chisholm and Mason (CM). Our objective was to evaluate the frequency of SS in patients with dry symptoms using FS and CM and to evaluate the degree of inter and intra-observer concordance of the histopathological reading by both methods.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study design. All patients with dry symptoms and studies to perform the SS classification criteria (2016) were included. The samples were independently evaluated by two readers. Descriptive statistics was used for the calculation of SS frequency. Agreement (Cohen’s Kappa coefficient) was analysed (STATA) for each test (CM and FS). Ethics approval was obtained.

Results92 patients were included. According to the 2016 criteria, SS was reported in 26.1% patients in whom FS was used and in 34.8% patients in whom CM was used. The degree of intra-observer concordance for the diagnosis of FLS was perfect and moderate-high for observers. Inter-observer agreement was substantial, with kappa values of .77 FS and .75 CM.

ConclusionsFS method is a more detailed and specific score that facilitates correct classification. The use of CM as a histopathological classificatory method for SS includes more patients when compared with FS. These results are of relevance to standardise the reading of LSG biopsy in specialized services attending SS patients.

Los criterios de clasificación del síndrome de Sjögren (SS) (ACR/EULAR-2016) incluyen la biopsia de glándula salival menor (BGSM), la cual utiliza el puntaje de focos (Focus Score/FS), pero en algunos casos sigue basándose en Chisholm y Mason (CM). Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la frecuencia de SS en pacientes con síntomas secos, mediante el uso de FS y CM y el grado de concordancia inter e intraobservador de la lectura por ambos métodos.

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes con síntomas secos y estudios para realizar los criterios de clasificación SS (2016). Dos lectores hicieron la evaluación independiente. Se utilizó estadística descriptiva para el cálculo de la frecuencia de SS. Se analizó la concordancia interobservadores e intraobservadores (Kappa de Cohen) (STATA) para cada prueba (CM y FS). Se obtuvo aprobación ética.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 92 pacientes. Se clasificó SS en el 26,1% de los pacientes en quienes se empleó FS y en el 34,8% en quienes se empleó CM. El grado de concordancia intraobservador fue perfecto y moderado-alto para los observadores. La concordancia interobservador fue sustancial, con valores de kappa de 0,77 FS y 0,75 CM.

ConclusionesEl método FS es una puntuación más detallada y específica que facilita una correcta clasificación. El uso de CM como método de clasificación histopatológica para SS incluye más pacientes en comparación con FS. Estos resultados son relevantes para unificar la lectura de la BGSM en los servicios que atienden pacientes con SS.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disease that primarily causes inflammation in the exocrine, lacrimal, and salivary glands. Its main clinical presentation is the dry syndrome (xeropthalmia, xerostomia) but it can also occur as a systemic autoimmune disease, up to a lymphoproliferative condition. Regarding its epidemiology, approximately of 200 patients who consult annually for dry syndrome, about 54% have SS, and its prevalence ranges between 0.01% and 0.72%. Predominantly affects women, compared with men (10/1 ratio).1,2

Currently, the criteria used for the diagnosis of this disease are those proposed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatic Diseases (EULAR)3,4 of 2016 which include objective measurement of the salivary flow, xeropthalmia measured by ocular staining score (fluorescein and lissamine) and the Schirmer test, as well as the antibodies against RO antigen (anti-RO/SSA) and the minor salivary gland biopsy (MSGB) in search of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis (FLS) read using the focus score (FS) method. A score is assigned to each item, and the sum of the scores higher than or equal to 4 points is indicative of SS. It should be clarified that anti-RO/SSA and MSGB criteria have an indicative of 3 points each, which makes them relevant and denotes the importance of the immunological component of these two aspects used for the diagnosis of SS.

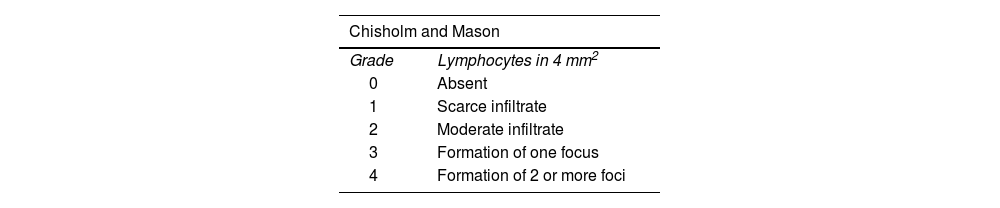

With respect to the MSGB, its importance for diagnosis and prognosis in SS should be highlighted. The definition of focus, according to Greenspan and Daniels,5 refers to the accumulation of 50 or more mononuclear cells. More recently, was introduced the calculation of FS,6–8 which refers to the number of foci in an area of 4 mm2 of normal-appearing tissue. The finding ≥1 focus in 4 mm2 of glandular tissue is called FLS. The presence of FS ≥ 1 is considered the histological manifestation characteristic of SS.8,9 Different methodologies have been proposed for the reading of MSGB. Despite FS is the suggested method, it is not routinely performed, since in some cases the Chisholm and Mason (CM) method is still used as a basis, even though this method does not distinguish FLS from chronic non-specific sialadenitis, an inflammatory disorder not typically associated with autoimmunity,8 which creates difficulty in reaching an accurate diagnosis of SS, given that the classification criteria currently used use the FS method as a basis.

Based on what was mentioned in the preceding paragraphs it is important to have a standardization regarding the method of reading the MSGB, since together with the rest of the symptoms and paraclinical findings typical of SS it can generate an impact on the prevalence and incidence of the disease.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the frequency of SS in patients with dry symptoms in a hospital in Bogotá, Colombia, between September 2019 and June 2020, using two histopathological methods (FS and CM), and, additionally, to evaluate the degree of inter- and intra-observer concordance of the histopathological reading of MSGB by means of FS and CM for the diagnosis of FLS.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study with non-probability sampling was conducted. Patients with dry symptoms who underwent the MSGB at the Hospital de San José (Bogotá-Colombia) between September 2019 and June 2020 were consecutively selected.

All patients with at least one symptom of ocular or oral dryness, defined as a positive response to at least one of the questions about the presence of dryness (Table 1) defined according to the ACR/EULAR (2016) classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome,4 and who had the clinical (eye stains, Schirmer test and unstimulated salivary flow test) and paraclinical (anti-Ro antibodies) tests available to be able to apply them and thus determine which patients would or would not meet these criteria were included. Patients with salivary gland biopsy specimens that did not meet the quality criteria for reading thereof (paraffin block material not suitable for study [insufficient of exhausted material, alterations due to archiving and/or manipulation] or histological material with salivary gland with less than 4 lobes surgically separated [or 6 lobes if they were small or with a surface area of less than 8 mm]).7

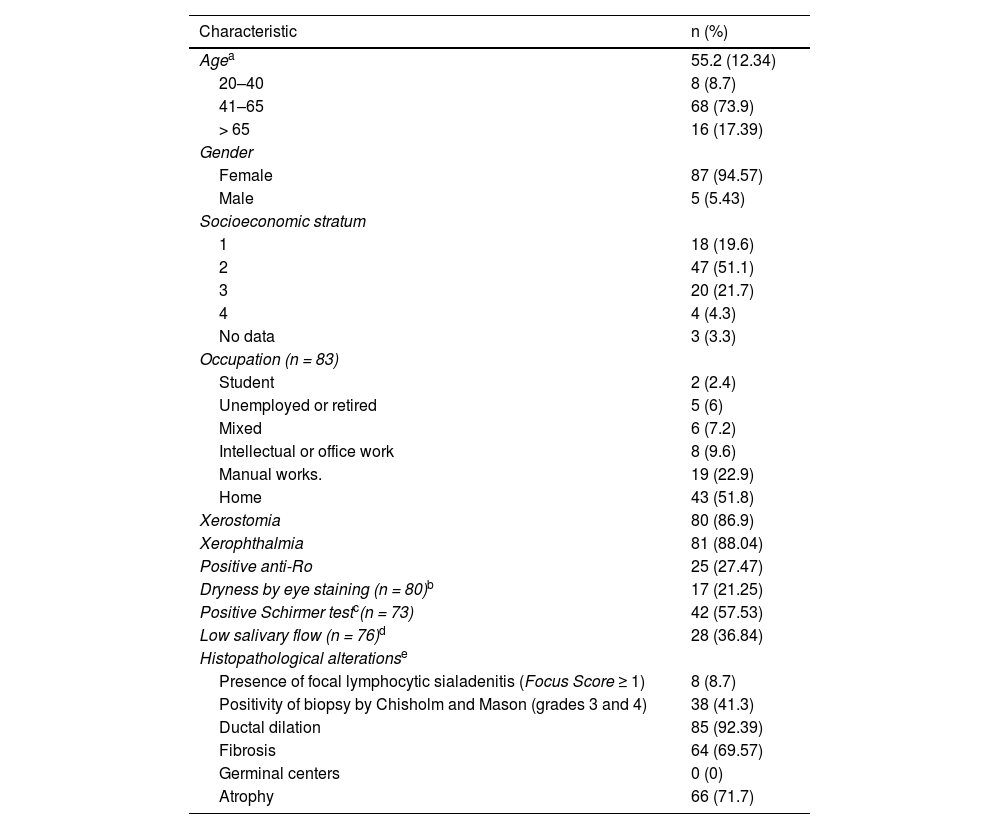

Characteristics of the included individuals and frequency of Sjögren’s syndrome according to the two histopathological techniques.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Agea | 55.2 (12.34) |

| 20–40 | 8 (8.7) |

| 41–65 | 68 (73.9) |

| > 65 | 16 (17.39) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 87 (94.57) |

| Male | 5 (5.43) |

| Socioeconomic stratum | |

| 1 | 18 (19.6) |

| 2 | 47 (51.1) |

| 3 | 20 (21.7) |

| 4 | 4 (4.3) |

| No data | 3 (3.3) |

| Occupation (n = 83) | |

| Student | 2 (2.4) |

| Unemployed or retired | 5 (6) |

| Mixed | 6 (7.2) |

| Intellectual or office work | 8 (9.6) |

| Manual works. | 19 (22.9) |

| Home | 43 (51.8) |

| Xerostomia | 80 (86.9) |

| Xerophthalmia | 81 (88.04) |

| Positive anti-Ro | 25 (27.47) |

| Dryness by eye staining (n = 80)b | 17 (21.25) |

| Positive Schirmer testc(n = 73) | 42 (57.53) |

| Low salivary flow (n = 76)d | 28 (36.84) |

| Histopathological alterationse | |

| Presence of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis (Focus Score ≥ 1) | 8 (8.7) |

| Positivity of biopsy by Chisholm and Mason (grades 3 and 4) | 38 (41.3) |

| Ductal dilation | 85 (92.39) |

| Fibrosis | 64 (69.57) |

| Germinal centers | 0 (0) |

| Atrophy | 66 (71.7) |

| Frequency of Sjögren’s syndrome according to the two histopathological techniquesf | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sjögren's syndrome including MSGB criteria with focus scoren = 24 (26.09%) | Sjögren’s syndrome including MSGB criteria with Chisholm and Masonn = 32 (34.78%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 24 (100) | 32 (100) |

| Male | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ]Age | ||

| 20–40 | 2 (8.3) | 2 (6.2) |

| 41–65 | 20 (83.3) | 25 (78.1) |

| > 65 | 2 (8.3) | 5 (15.6) |

MSGB: Minor salivary gland biopsy.

Source: Own elaboration.

The following questions (positive response to at least one) were applied to include the patients with ocular or oral dryness and proceed to determine the presence or absence of Sjögren’s syndrome, according to the compliance with the 2016 criteria, using each of the two histopathological techniques to establish the positivity or negativity of the minor salivary gland biopsy criterion (the median and interquartile range [IQR] are presented in months of duration of the symptoms in the cases in which the response was positive): 1) Have you had daily persistent dry eye discomfort for more than 3 months? (12 IQR 30). 2) Have you had a recurring sensation of sand or gravel in your eyes? (12 IQR 23). 3) Do you use tear substitutes more than 3 times a day? (3 IQR 12). 4) Have you had a daily sensation of dry mouth for more than 3 months (12 IQR 18). 5) Do you often drink liquids to help swallow dry foods? (12 IQR 24).

The histological slides were independently evaluated by two second-year pathology resident physicians, with previous training during their two years of formation by a pathologist expert in MSGB reading. These residents had specific training in their first and second years of residency in MSGB reading and in both histopathological methods. During the training sessions, the reading of the histopathological slides was reviewed by the expert pathologist professor to clarify the terms, doubts and standardization of the reading. At the end of each training, the residents had a test, which had to contain all the questions answered correctly, in order that their training in this reading was considered approved. The evaluators remained blinded to clinical and patient identification data during each reading. The slides were coded with random numbers, so that the reader would not have memory bias for subsequent readings of the same slide. The readings were performed at intervals of one week, for a total of 4 for each reader (two by the FS method and two by CM). For the analysis of the interobserver concordance, the first reading performed by each observer with each of the methods was used, while in the case of the definitive diagnosis of FLS and of the histopathological alterations (Table 1) the disagreements on the first readings were evaluated, and then were resolved by the pathologist expert in MSGB for a definitive diagnosis.

FLS was defined as the presence of focal aggregates of 50 or more lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages that replace the acinar structure, being present when it was ≥1 focus/4 mm2, and absent when there was <1 focus/4 mm2, following the standardization measures for MSGB reading proposed by the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Study Group.7 In turn, for the evaluation using the CM method, the presence of focal aggregates of 50 or more lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages that replace the acinar structure was considered, being present in grades 3 and 4 and absent in grades 0, 1 and 2 (according to the number of foci/mm2, where 0 = none, 1 = scarce infiltrate, 2 = moderate infiltrate, 3 = one focus (≥50 cells) and 4: ≥2 foci).10 Other characteristics were described at the time of the pathological reading, such as the presence of atrophy, fibrosis, ductal and germinal center dilation.

The sociodemographic variables (sex, age, occupation, stratum) were obtained from the clinical history, as well as all the variables concerning the ACR/EULAR 2016 criteria.4

The frequency of SS was calculated through the proportion between patients who met the ACR/EULAR 2016 classification criteria and the total population studied, by involving the two histopathological methods, with calculation together with the other variables of the criteria assessed by a rheumatologist epidemiologist. A score ≥4 was considered positive for SS according to the ACR/EULAR 2016 criteria.4

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the variables of interest was performed using absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables and by measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables. Likewise, mean and standard deviation were used, or median and interquartile range (IQR, defined by the first and third quartiles) depending on the normality of their distribution. This normality was assessed using the Shapiro Wilks and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests.

Concordance was assessed using the Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The inter- and intra-observer agreement was analyzed for each test (CM and FS), after the resolution of disagreements by a third observer. The scale described by Landis y Koch was used to classify the strength of the agreement (kappa value 0.00–0.20, weak; 0.21–0.40, mild; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial or high; and 0.81–1.00, almost perfect).

Data analysis was performed using the STATA software.

The institution’s ethics committee approved the study (CEISH, Act 0457-2018) and informed consent was obtained from the patients. The research team complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and the national regulations on research ethics (Resolution 8430 of 1993).

ResultsA total of 92 patients with dry symptoms who met the selection criteria, with a mean age of 55.2 years (standard deviation, SD = 12.34), most of them women (n = 87; 94.57%) were included.

Presence of xerostomia was observed in 80 (86.96%) patients and xerophthalmia in 81 (88.04%) of them. The mean duration of the dry symptomatology in most of the 5 questions related to dryness was 12 months; the details of its duration is found at the bottom of Table 1. About a quarter of the patients were anti-RO positive (27.4%) and 36% had unstimulated salivary flow less than 1 ml/min. In addition, 21% and 57% of patients were positive for the ocular staining and Schirmer’s test, defined according to the ACR/EULAR 2016 criteria, respectively. The general sociodemographic, clinical and histopathological characteristics are presented in Table 1.

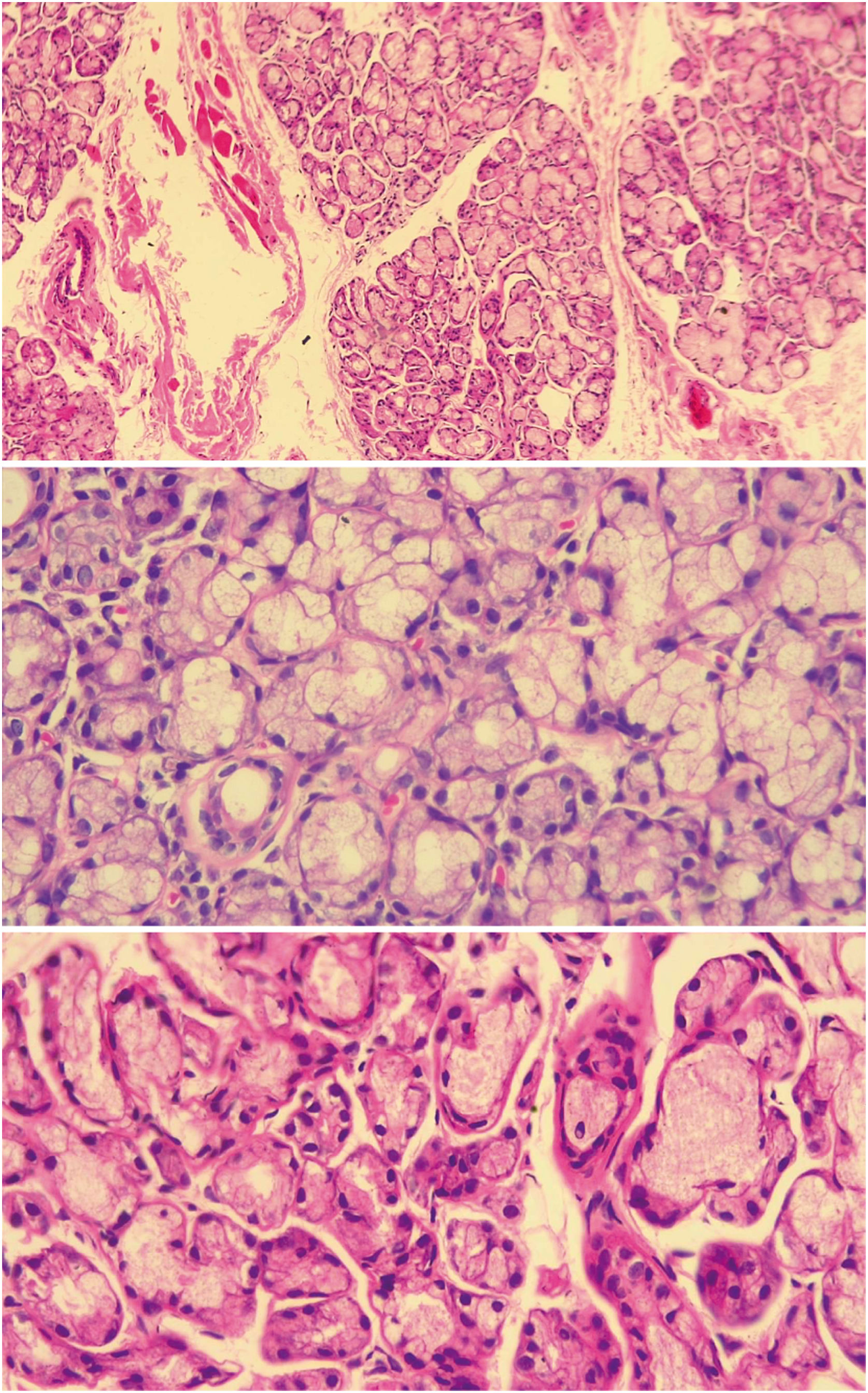

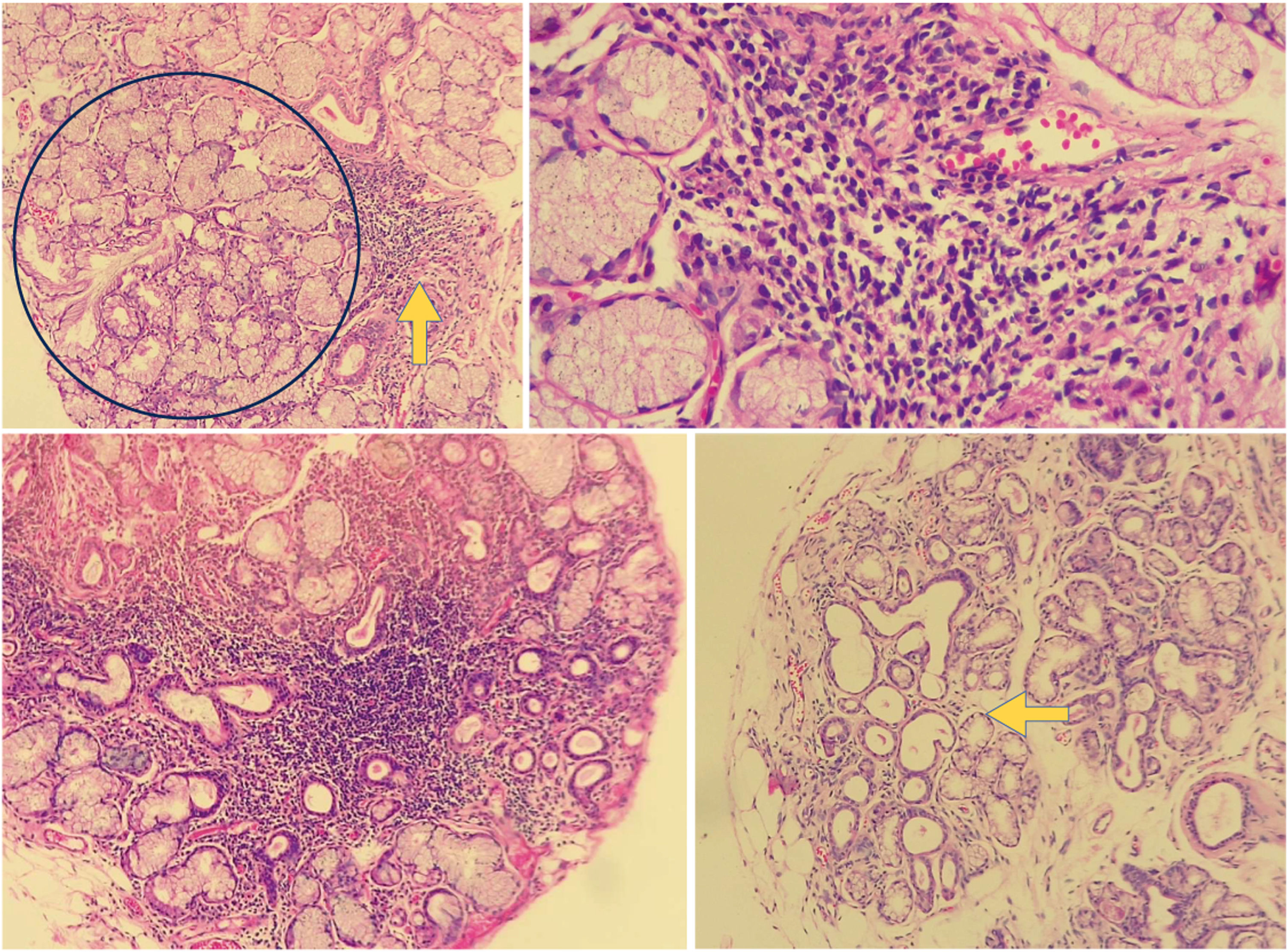

Of the total of patients with dry symptoms, FLS was found in 8 (8.7%) of them (see Figs. 1 and 2), according to the FS (the focus score was found between l and 2 in 7 of the patients and only in one was higher than 2, while 38 (41.30%) had a positive biopsy by CM (grades 3 and 4). All patients who were positive by the CM method, but who were negative for SS when the FS classification was used, had chronic non-specific sialadenitis by said method, except one who presented chronic sclerosing sialadenitis. According to the ACR/EULAR criteria scores (2016), the frequency of SS was determined in 24 (26.09%) patients when the FS method was used for MSGB (this frequency included the 8 with positivity for FLS according to FS) and in 32 (34.78%) patients when the CM method was used; all cases were recorded in women. The remaining 6 patients with positivity by CM were classified as patients with dry syndrome, who, although they were positive through this reading in the MSGB, were not positive in the other criteria for SS. With respect to age, the highest frequency of SS was between 41 and 65 years for both histopathological methods (FS: 83.3%; CM: 78.3%).

Histology of normal minor salivary gland. A salivary gland with normal histology of a patient included in the study is observed in the three slices, in which mucinous acini with myoepithelial cells and ductus are seen. The upper image at 10× magnification and the lower images at 40× magnification. Source: own elaboration.

Histology of an altered minor salivary gland. The upper left image shows a salivary gland biopsy of a patient included in the study, in a 10× slice with an aggregate of lymphoid cells (yellow arrow) adjacent to a normal-appearing salivary gland (blue circle). In the upper right image, the same aggregate is observed at a magnification of 40×. This aggregate can be counted as a focus. In the lower left image, a dense aggregate of lymphocytes is observed in the salivary gland background of one of the patients analyzed in the study, with atrophy and ductal dilation. In the lower image on the right, we can see a salivary gland biopsy with ductal ectasia (arrow) and atrophy. Source: own elaboration.

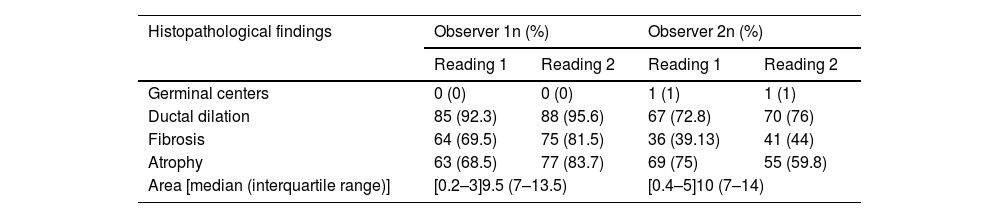

When evaluating the degree of intraobserver concordance for the histopathological reading of the minor salivary gland biopsy using the FS and CM methods for the diagnosis of FLS, perfect concordance was observed with the 2 methods for observer 1 and substantial or high concordance for observer 2, with kappa values of 0.76 and 0.80 for the reading when FS and CM were used, respectively.

Regarding the degree of interobserver concordance, simple agreement percentages of 95.65% were found in the reading with FS and 88.04% for the reading with CM, with a substantial concordance, with kappa values of 0.77 and 0.75, respectively (Table 2).

Frequency of histopathological findings between observers and intra- and inter-observer agreement.

| Histopathological findings | Observer 1n (%) | Observer 2n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading 1 | Reading 2 | Reading 1 | Reading 2 | |

| Germinal centers | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Ductal dilation | 85 (92.3) | 88 (95.6) | 67 (72.8) | 70 (76) |

| Fibrosis | 64 (69.5) | 75 (81.5) | 36 (39.13) | 41 (44) |

| Atrophy | 63 (68.5) | 77 (83.7) | 69 (75) | 55 (59.8) |

| Area [median (interquartile range)] | [0.2–3]9.5 (7–13.5) | [0.4–5]10 (7–14) | ||

| Intra-observer agreement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Intra-observer agreement and kappa for Focus Score | 100% k = 1 (p < 0.001) | 94.57% k = 0.76 (p < 0.001) |

| Intra-observer agreement and kappa for Chisholm and Mason | 100% k = 1 (p < 0.001) | 90.22% k = 0.80 (p < 0.001) |

| Inter-observer agreement | |

|---|---|

| Interobserver agreement for Focus Score | 95.65% k = 0.77 (p < 0.001) |

| Interobserver agreement for Chisholm and Mason | 88.04% k = 0.75 (p < 0.001) |

Source: own elaboration.

The diagnosis of SS is complex, due to the variety of clinical and paraclinical alterations. MSGB is an important criterion for the accurate classification of the disease, but it can be influenced by the method of histological interpretation and the experience of the pathologist, which can lead to an under- or overestimation of patients with SS.6,11

In previous studies, which used different classification criteria (2002 or 2012)3,12 to assess the prevalence of SS, prevalences of approximately 20 to 30% have been demonstrated.13–15 In the present study, the frequency of SS was analyzed (26.09% using FS and 34.78% using CM), and it was found a tendency to conclude a higher frequency of SS with the CM method. At present there are no studies that evaluate the frequency of SS, comparing the two histopathological methods mentioned.

There are different methods for the interpretation of the MSGB (Table 3)6: the CM (1968) includes 5 grades, according to the presence of mild or moderate lymphocytic infiltration and/or focus of lymphocytes10; Greenspan and Daniels (1974),5 who added the concept of Focus Score (FS) currently used in the criteria for SS4; and Tarpley (1974),16 who introduced the concepts of acinar destruction and fibrosis. To date, there are no studies that directly compare the sensitivity and specificity of these methods. Despite the fact that the FS is the standardized method within the current classification criteria for SS, the CM method is still used in some centers,17,18 although the number of studies that used this scoring system was higher before the ACR/EULAR 2016 classification criteria.19,20

Morphological criteria of two histopathological methods for the diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome in minor salivary gland biopsy.

| Chisholm and Mason | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Lymphocytes in 4 mm2 |

| 0 | Absent |

| 1 | Scarce infiltrate |

| 2 | Moderate infiltrate |

| 3 | Formation of one focus |

| 4 | Formation of 2 or more foci |

| Focus: 50 or more mononuclear cells in periductal or perivascular areas. | |

|---|---|

| Focus Score | |

| Atrophy | Loss of glandular parenchyma |

| Adiposis | Replacement of the parenchyma by adipocytes |

| Ductal ectasia | Dilation of the lumen of the duct and flattening of the lining epithelium |

| Fibrosis | Collagen fibers around the ducts or acini |

| Germinal centers | Well-circumscribed infiltrate of B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes in smaller amounts, tingible body macrophages and follicular dendritic cells |

| Focal lymphocytic sialadenitis | Presence of one or more foci containing dense aggregates of 50 or more lymphocytes (most are several hundred or more) that are typically found in perivascular or periductal locations. These foci must be adjacent to normal-appearing mucosal acini. The lobes or lobules must lack ductal dilation and contain scarce plasma cells. This diagnosis is assigned when these foci are the only inflammation present in a specimen, or the most prominent feature. The focus score can be calculated when focal lymphocytic sialadenitis is present |

| Total number of foci in the sample by the total area of the gland in mm2, multiplying the result by 4. A focus score positive for Sjögren syndrome is considered when it is ≥ 1 focus/4 mm2 | |

Source: modified and adapted from Parra-Medina et al.6

Some studies have evaluated the concordance between FS and CM. Peña Carvajalino et al.,8 evaluated it, and found that the agreement between the 2 tests for FLS was week (kappa 0.13), agreement that was not calculated in the present study. In addition, in the study in question the authors found interobserver agreements moderate for FS (k = 0.47) and high for CM (k = 0.65), data that agree with those found in our study. Likewise, Costa et al.19 evaluated the intraobserver and interobserver reliability of the MSGB in SS in 14 university hospitals in France; the interobserver agreement between local pathologists and trained pathologists was moderate for FS (k = 0.71) and CM (k = 0.64). It should be noted that, in the present study, the agreement was slightly higher for FS than for CM (0.77 vs. 0.75), which contrasts with the results of the study conducted by Costa et al.19 However, the authors highlight that the majority of local pathologists based their diagnoses on the CM reading, even though in the daily readings they provided data with which the FS could be calculated a posteriori. Finally, the degree of intraobserver agreement was almost perfect (k = 1) for FS and substantial for CM (k = 0.8), with results similar to those of the present study.

Some studies8 have evaluated the discrepancies between the findings of FLS when performed by FS, compared with CM, highlighting that the latter does not distinguish between the inflammation patterns of FLS and the finding of chronic non-specific sialadenitis. In our study, only 8.7% of the cases evaluated had FLS assessed by FS, in contrast to 41.3% of the cases diagnosed as FLS with CM. These differences may overestimate the frequency of SS, as observed in our study. For the correct calculation of the FS, lymphoid aggregates that are not adjacent to tissue with chronic changes, alterations such as atrophy, fibrosis or ductal dilation should be considered, since these findings do not favor an adequate calculation. It should be noted that this has been controversial, given that such findings may be frequent in the general population and can also occur in SS.6 In the standardization for the histopathological interpretation of the MSGB in clinical trials, proposed by Fisher et al.,7 it is concluded that the finding of FLS cannot be considered when the histological appearance of the glands is predominantly attributable to chronic non-specific sialadenitis (fibrosis, ductal dilation and atrophy) and without evidence of foci adjacent to normal parenchyma. In this case the FS cannot be calculated. It is possible that these precisions for the calculation of the FS, which are not contemplated by the CM scoring system, influence a lower proportion of individuals classified as SS compared to the CM classification, when they are taken into account within the classification criteria for SS, as in our study.

In a recent study18 with a population similar to ours, in which the pathology reports of nearly one thousand patients with dry symptoms who underwent MSGB were retrospectively evaluated, it was found that the CM scale was the most frequently used by pathologists (55.1%), followed by the Greenspan scale (46.5%), and in a quarter of the patients, both scales were reported. When the interobserver concordance between rheumatologists and pathologists was compared at the time of interpreting the findings described in the pathology report regarding the CM score 3 or 4, it was found that it was moderate (k = 0.57); the pathologists most frequently assigned a score of 3, while the rheumatologists assigned a score of 4. It should be highlighted that in this study the finding of fibrosis was reported in 25.4%, as well as atrophy in 19% and the two findings in 7.7%, which contrasts with our study, in which we found fibrosis in 69.5% and atrophy in 71%. This is important because at the time of evaluating the FS score, as mentioned above, when the appearance of the gland is predominantly attributable to chronic non-specific sialadenitis (fibrosis, atrophy, etc.) the FS cannot be adequately calculated. This, therefore could reflect the low frequency of FLS assessed by FS in the present study.

It is noteworthy that in the present study no germinal centers were found, which has been described as present in about 30 to 40% of patients with SS in a previous metaanalysis.11 However, in that study they did not find an association of this finding with specific clinical manifestations, but they did find an association with a characteristic serological subphenotype (positivity for anti-Ro, anti-La and rheumatoid factor). Our finding of absence of germinal centers is similar to the study conducted by Vivas et al.18 in a population similar to ours. Some authors21 have considered that the presence of germinal centers is associated with a late stage of the disease and, in turn, with high focus scores. In the present study the median of dry symptoms was no longer than one year (Table 1) and the focus score was low, which could partly explain the absence of germinal centers in the patients analyzed.

On the other hand, Tavoni et al.,17 in a study conducted in different Italian centers and that involved 50 MSGBs evaluated in daily routine practice, found a moderate interobserver concordance (k = 0.75) when the final histopathological finding was evaluated as consistent of non-consistent with SS by CM, but when the independent scores were evaluated, the discrepancies were greater, which impacted the final diagnosis of SS. Something similar was found in our study, given that the proportion of patients classified as SS was much higher when the CM system was used. It is noteworthy that the authors of this study17 highlight its weakness when using the CM score, which is old and less specific and reproducible than the FS scoring system; however, to date, various Italian centers continued using it.

On the other hand, Carubbi et al.,22 one year before the publication of the new ACR/EULAR 2016 classification criteria for SS,4 retrospectively evaluated the prognostic value of MSGB in 794 patients with SS, when it was analyzed using both CM and FS, and they found that the FS allowed the identification of a series of differences in the spectrum of the disease, as well as the prognostic value, since they observed an association between the FS value and the clinical-serological variables. In contrast, when patients were divided according to the CM grading system no significant difference was observed between the subgroups.

The present study has several weaknesses; among them is the evaluation of the scoring systems by pathology residents, although it is clarified that they had specific training and disagreements were resolved with the expert pathologist. However, interobserver agreement between the residents and the expert was not performed before starting the study. Furthermore, the agreement between the two reading methods was not analyzed, as other studies available have done in a population similar to the one analyzed here8; however, we did not consider it since a priori it could be expected to be good, given that the FS method is derived from the CM method.23 It should be clarified that the design of our study prevents from establishing a conclusion regarding the diagnostic performance, since it was not a study of diagnostic tests and should be analyzed in the light of its design and the objective of establishing the frequency of SS.

ConclusionThe FS method is a more detailed and specific score that facilitates correct classification. On the other hand, the use of CM as a histopathological method when compared to FS for classification criteria includes more patients as SS; however, this scoring system has several weaknesses, among them, not considering the alterations typical of chronic non-specific sialadenitis, overestimating in some cases the positive finding for SS when compared with the FS method and, on the other hand, the absence of association as a determinant of the prognostic factor. Therefore, we consider that these results are relevant to unify the reading of the MSGB in the services that care for patients with SS, using the FS, which is the scoring system recommended by the current classification criteria for SS.

FundingThis work was founded by the Research Promotion Call of the Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS) (Act nº 13 of December 6, 2019 DI-I-1387-19).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest related to the preparation of this article.

We would like to thank all the support staff and histology technicians of the Hospital de San José, who helped us to collect the histological materials of minor salivary gland biopsy, necessary for the processes performed in this study.