Detection and decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus prior to surgery is postulated as an option to reduce the risk of infection in arthroplasties. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a screening programme for S. aureus in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA), the incidence of infection with respect to a historical cohort, and its economic viability.

Material and methodsPre-post intervention study in patients undergoing primary knee and hip prostheses in 2021, a protocol was carried out to detect nasal colonization by S. aureus and eradication if appropriate, with intranasal mupirocin, post-treatment culture with results three weeks between post-treatment culture and surgery. Efficacy measures are evaluated, costs are analyzed and the incidence of infection is compared with respect to a historical series of patients operated on between January and December 2019, performing a descriptive and comparative statistical analysis.

ResultsThe groups were statistically comparable. Culture was performed in 89%, with 19 (13%) positive patients. Treatment was confirmed in 18, control culture in 14, all decolonized; none suffered infection. One culture-negative patient suffered from Staphylococcus epidermidis infection. In historical cohort: three suffered deep infection by S. epidermidis, Enterobacter cloacae, Staphylococcus aureus. The cost of the programme is €1661.85.

ConclusionThe screening programme detected 89% of the patients. The prevalence of infection in the intervention group was lower than in the cohort, with S. epidermidis being the main micro-organism, different from S. aureus described in the literature and in the cohort. We believe that this programme is economically viable, as its costs are low and affordable.

La detección y descolonización del Staphylococcus aureus previo a la cirugía, se postula como la opción para disminuir el riesgo de infección en artroplastias. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la efectividad de un programa de cribado de S. aureus en la artroplastia total de rodilla (ATR) y en la artroplastia total de cadera (ATC), la incidencia de infección respecto a una cohorte histórica y su viabilidad económica.

Material y métodosEstudio pre-postintervención en pacientes intervenidos de ATR y ATC en al año 2021. Se realizó protocolo de detección de colonización nasal por S. aureus y erradicación si procedía, con mupirocina intranasal, cultivo postratamiento con el resultado de 3 semanas entre cultivo postratamiento y cirugía. Se evalúan medidas de eficacia, se analizan costes y se comprara la incidencia de infección respecto a una serie histórica de pacientes intervenidos entre enero y diciembre de 2019, realizando análisis estadístico descriptivo y comparativo.

ResultadosLos grupos fueron comparables estadísticamente. Se realizó el cultivo en el 89%, siendo 19 (13%) pacientes positivos. Se confirmó el tratamiento en 18, cultivo control en 14, todos descolonizados; ninguno sufrió infección. Un paciente con cultivo negativo sufrió infección por S. epidermidis. En cohorte histórica: 3 sufrieron infección profunda por S. epidermidis, E. cloacae y S. aureus. El coste del programa fue de 1.661,85€.

ConclusiónEl programa de cribado detectó el 89% de los pacientes. La prevalencia de infección en el grupo intervención era menor que en la cohorte, siendo S.epidermidis el microorganismo causante, diferente a S. aureus descrito en la literatura y en la cohorte. Consideramos que este programa es económicamente viable, siendo sus costes reducidos y asumibles.

Infection of the prosthesis is one of the most feared complications in total arthroplasties of the hip (THA) and knee (TKA). It has a prevalence of from 1% to 3% in total knee arthroplasty and from 0.7% to 2.5% in hip arthroplasty.1

Infection of the prosthesis increases the duration of hospitalization, leads to multiple interventions, delays recovery and increases the risk of mortality.2 Furthermore, direct medical costs after revision surgery of THA or TKA increase greatly, above all in cases of surgery in 2 acts.3,4

Several risk factors are associated with infection of the prosthesis2; colonization by nasal5 or cutaneous6,7Staphylococcus aureus is one such factor, although it is not clear whether it is solely due to the colonization, or to a combination of this with other factors,6,8 given that infections by the said micro-organism may also arise in patients who are not carriers.6

The Staphylococcus species is the main causal agent of infection of the surgical site and prosthesis, in more than 60% of cases.8 Of these, in some series coagulase negative staphylococcus (CNS) such as Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus predominate, while in other series, such as the one by Sousa et al., the predominant agent is S. aureus, in 41.2% of cases; the remaining 17.6% are methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA) and 23.5% are sensitive (MSSA).6 MRSA strains are more virulent, and treating them is more complex.9

S. aureus is a commensal micro-organism which is found in the skin and mucus membranes of 30% of the patients who are subjected to a total arthroplasty,6–8 and in 1% of these cases it is MRSA. Some longitudinal studies show that up to 20% of the population are permanent carriers of S. aureus and that 30% are intermittent carriers.10

Some protocols, studies and institutions recommend the nasal decolonization of S. aureus prior to surgery, with the aim of reducing the risk of prosthesis infection.11 Nevertheless, there is no general consensus on this, as logistical and economic implications have to be taken into consideration.12

With respect to the nasal decolonization protocol, retrospective studies suggest that universal preoperative treatment with topical antiseptic and the examination, detection and treatment of carriers may both be beneficial, as they reduce infections of the surgical site in general. This is also so specifically for S. aureus and MRSA after orthopaedic surgery, although there is no consensus as to which of the two methods is the most efficient and cost-effective.9 There are different alternative methods of screening: on the one hand, there is standard culture that may be exclusively nasal or taken from different areas of the body, with variable sensitivity, or detection techniques using molecular polymerase chain reason (PCR). Although the latter gives results more quickly, it is more expensive and has not been shown to have any clear advantage.13,14

Decolonization treatment consists of intranasal mupirocin which may or may not be combined with the topical chlorhexidine gluconate used in the shower.15 Although detection and decolonization protocols have been shown to be highly successful, some studies have demonstrated that colonization persists in up to 20% of cases.7,16–18 It is therefore important to confirm decolonization at least 3 weeks prior to surgery.11

The objectives of this study are to evaluate the efficacy of a S. aureus screening and decolonization programme in total arthroplasties of the hip and total arthroplasties of the knee in terms of their ability to detect and decolonize, evaluating the incidence of infection in comparison with a historical cohort. It also finally assesses its economic feasibility.

Material and methodsA study of the intervention was undertaken in comparison with a historical cohort of patients operated for TKA and THA in our hospital in 2019 and 2021. The year 2020 was excluded due to major dysfunctions in the hospital, the department and circuits caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study was approved by the Research and Medication Ethics Committee (CEIM) of our hospital, with the code CEIC-2606.

The “Declaration of the Initiative Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): guidelines for the communication of observational studies” was followed.19

Anonymized data and variables are collected prospectively from a database created within the context of an “Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)”20 programme that has been applied since 2015 for the purpose of collecting data for analysis and continuous improvement. The variables recorded within the framework of this programme are: demographic data, average duration of hospitalization, transfusions, pain and analgesic rescues, screening for S. aureus and complications. Follow-up takes the form of a check-up at 90 days within the framework of the Catalonian infection monitoring programme (VINCAT), which involves the follow-up of at least the first 100 procedures performed every year; nevertheless, in our hospital active monitoring was expanded to include all arthroplasty surgery after 90 days.

All of the patients operated for primary TKA and THA in 2019 and 2021 for any diagnosis except femur fracture were eligible; septic or aseptic revision surgery was also excluded. The intervention group consisted of the patients operated from 1 January 2021 to 31 December 2021, who were subjected to the S. aureus screening and decolonization protocol; the control group consisted of the patients operated from 1 to 31 December 2019, when the said protocol was not applied.

The screening and decolonization protocol consists of the following steps: a request for a nasal swab for S. aureus is included as routine in the preoperative arthroplasty study for all of the patients in the orthopaedic and traumatology surgery department. The sample is taken in the primary medical care centre using a nasal swab at the same time as the preoperative analytical sample is taken, from 4 to 6 weeks prior to the operation. The result of the swab is examined in the preoperative anaesthesiology meeting: if the result is positive for S. aureus (MSSA or MRSA), the anaesthesiologist prescribes decolonization treatment with topical mupirocin every 8h during 5 days in the patient's home, commencing 10 days before the operation; this complies with the time limit described in the literature, which states that surgery should be performed within 3 weeks of decolonization,11 while offering the opportunity of remaining within the time limit if surgery is reprogrammed. The anaesthesiologist requests a follow-up swab after the decolonization treatment and prior to the surgery, and this swab too is performed by primary care. The Unidad Territorial de Infección Nosocomial (UTIN) and antibiotic policy reviews the result of the follow-up swab after the treatment. If the culture taken after the treatment is still positive for MRSA on the day of the intervention, the UTIN will warn the head of surgery and anaesthesiology so that they apply measures from the start of the process: antibiotic prophylaxis will be required, with 1g intravenous vancomycin in a single preoperative dose from 120 to 60min before the incision, contact measures during the whole surgical process and a second decolonization treatment 5–10 days later with mupirocin or fusidic acid.

The other measures applied to prevent infection were the same in both cohorts. The most notable measures include bathing using neutral soap in the home the day before surgery, and washing the zone to be operated with chlorhexidine soap by hospital staff on entry into the surgical area. The antibiotic prophylaxis protocol consists of a single preoperative dose of 2g intravenous cefazolin, except for patients who are allergic to penicillin, who receive 600mg teicoplanin. The surgical asepsis protocol, maintenance of normal temperature and glycaemia levels are the same for both groups.

The study variables recorded for both groups were: the joint that was operated, age, laterality, sex, ASA, infection of the surgical site 90 days after surgery, type of infection and the germ which caused it.

In the intervention group the application of the S. aureus detection culture was evaluated, together with its result and, if it were positive, its type (MRSA or MSSA); the decolonization treatment performed, the post-decolonization culture and its result; the 3-week period between the post-decolonization culture and surgery.

Data were gathered from three different sources. Firstly, the anonymized database of the ERAS programme was used to obtain the demographic variables and the data on the S. aureus detection culture and its result. Secondly, electronic clinical histories were used for the decolonization treatment data, the result of the post-decolonization culture and the data it was carried out. Lastly, the VINCAT programme database was used to detect the presence of infection after 90 days, the type of infection and the germ which caused it.

The variables are described as medians (interquartile range) or percentages. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the groups (with no normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) for continuous variables, and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. The level of significance was set at P<.05. Version 23.0 of the SPSS® software was used for calculations (SPSS, Chicago, Ill, USA).

The following direct costs were assumed for the economic analysis: the nasal swab to detect S. aureus costs 4.66€ according to the price set by the Instituto Catalán de la Salud (ICS), including the swab, the laboratory technique and labour; 20mg/g mupirocin cream costs 7.51€.

Any possible indirect costs are insignificant, as the patient's own health centre carries out the analysis at the same time as the preoperative analytical sample is taken, so that no extra travel, consumption or time is involved.

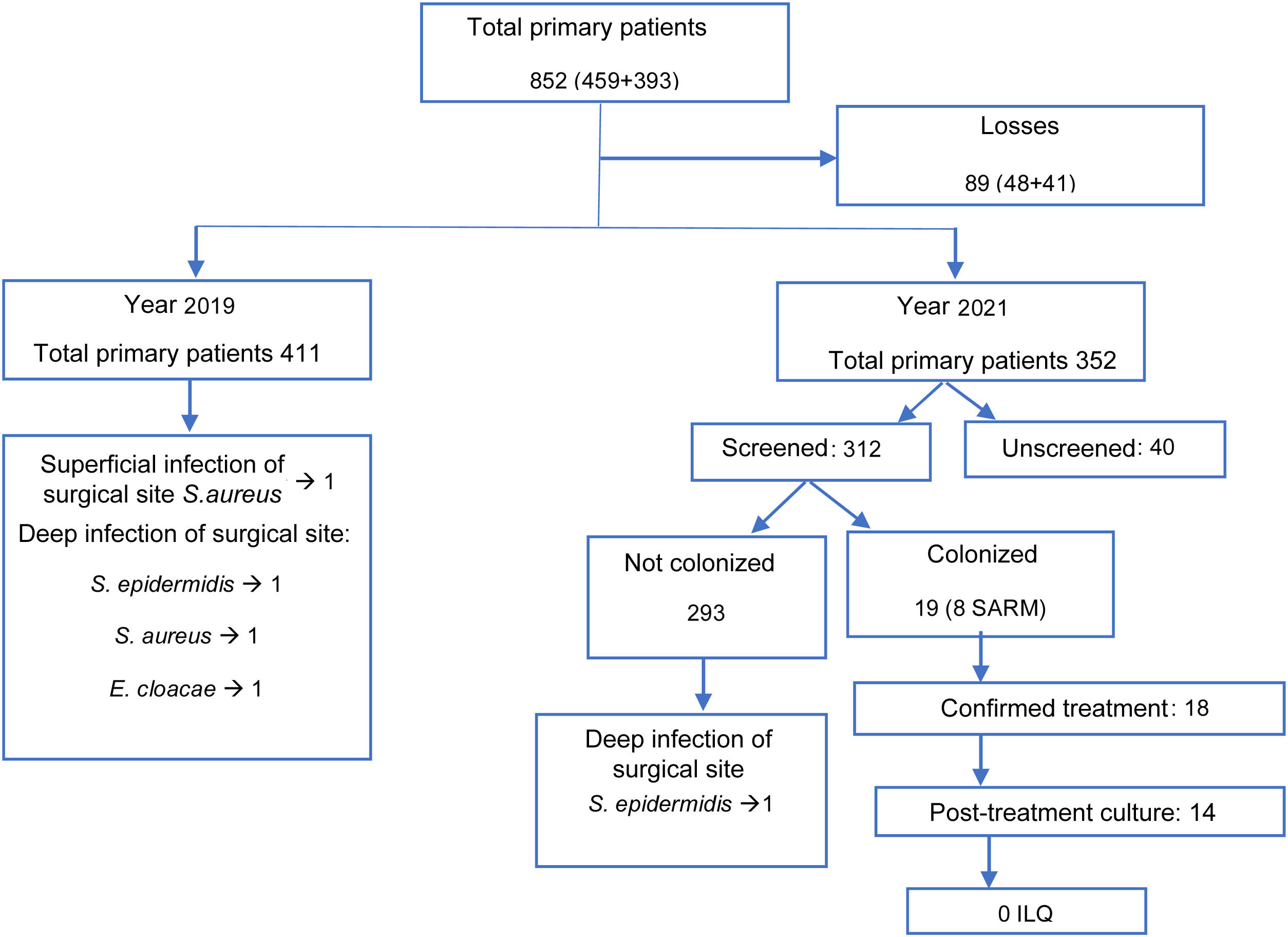

ResultsThe initial eligible population consisted of 852 patients who had been operated for TKA or THA in 2019 and 2021 (459 in the historic cohort of 2019 and 393 in the 2021 intervention group). 89 patients were lost (48 and 41, respectively), due to problems with their identification and registration in the database. The complete analyzed sample therefore amounted to 763 patients: 411 in the historic cohort and 352 in the intervention cohort (Fig. 1).

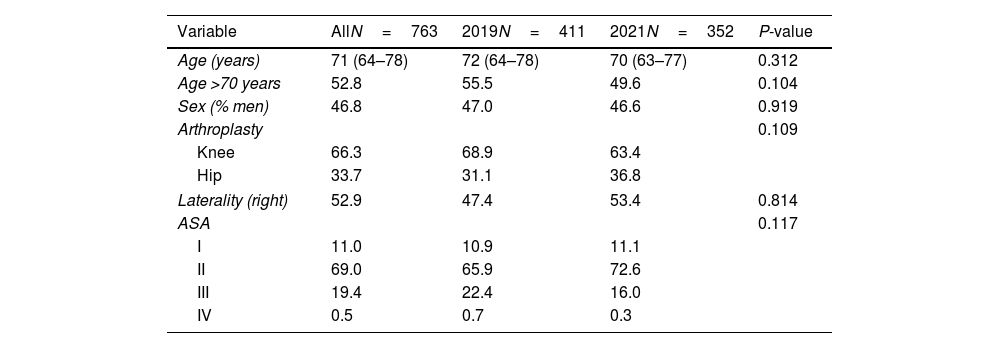

The sample obtained had a median age of 71 years (64–78), with 53.2% women and right laterality in 52.9% of cases. The predominant surgical risk level was ASA II. The surgical operation consisted of TKA in 66.3% of cases (68.9% in 2019 and 63.4% in 2021) and THA in 33.7% of cases (31.1% and 36.8%, respectively). No statistically significant differences were found between the characteristics of both groups (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the patients who received a prosthetic joint in the years 2019 and 2021 (n=763).

| Variable | AllN=763 | 2019N=411 | 2021N=352 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71 (64–78) | 72 (64–78) | 70 (63–77) | 0.312 |

| Age >70 years | 52.8 | 55.5 | 49.6 | 0.104 |

| Sex (% men) | 46.8 | 47.0 | 46.6 | 0.919 |

| Arthroplasty | 0.109 | |||

| Knee | 66.3 | 68.9 | 63.4 | |

| Hip | 33.7 | 31.1 | 36.8 | |

| Laterality (right) | 52.9 | 47.4 | 53.4 | 0.814 |

| ASA | 0.117 | |||

| I | 11.0 | 10.9 | 11.1 | |

| II | 69.0 | 65.9 | 72.6 | |

| III | 19.4 | 22.4 | 16.0 | |

| IV | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | |

ASA: classification according to American Society of Anesthesiologists guides; P-value: resulting from the Chi-squared or Mann–Whitney tests.

Values are expressed as a percentage or median (interquartile range).

Teicoplanin was given under protocol to patients who were allergic to penicillin. This glycopeptide may affect the prevalence of S. aureus infection. 7.79% of patients were given teicoplanin in the control group, and the corresponding percentage for the intervention group was 7.1%, without any significant differences between both groups (P=.1573).

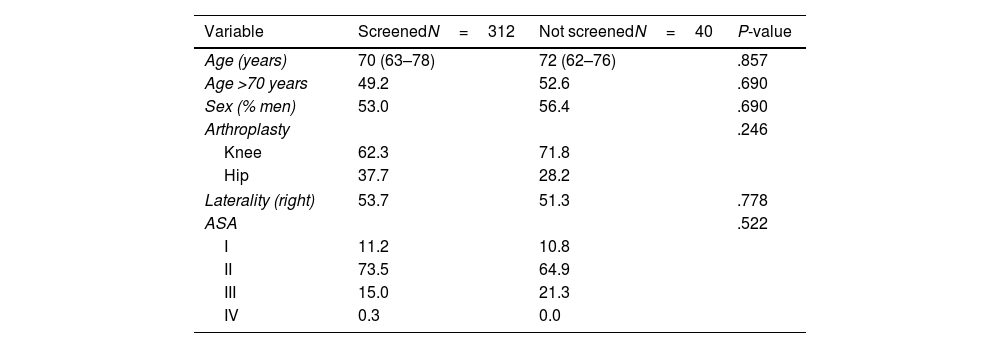

In the intervention group: screening was performed in 89% of cases, and it was positive for S. aureus in 19 cases (8 MRSA and 11 MSSA). No differences were observed in the demographic characteristics of the screened patients and those who were not screened (Table 2).

Demographic characteristics of the patients who received a prosthetic joint in the year 2021. According to screening application (n=352).

| Variable | ScreenedN=312 | Not screenedN=40 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70 (63–78) | 72 (62–76) | .857 |

| Age >70 years | 49.2 | 52.6 | .690 |

| Sex (% men) | 53.0 | 56.4 | .690 |

| Arthroplasty | .246 | ||

| Knee | 62.3 | 71.8 | |

| Hip | 37.7 | 28.2 | |

| Laterality (right) | 53.7 | 51.3 | .778 |

| ASA | .522 | ||

| I | 11.2 | 10.8 | |

| II | 73.5 | 64.9 | |

| III | 15.0 | 21.3 | |

| IV | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

ASA: classification according to American Society of Anesthesiologists guides; P-value: resulting from the Chi-squared or Mann–Whitney tests.

Values are expressed as a percentage or median (interquartile range).

Treatment was confirmed in 18 of the patients with a positive culture, and the follow-up culture was performed within the 3-week interval before surgery in 14; all of them were found to be decolonized, so that no additional measures were necessary during the surgical process. No patient with a positive detection culture suffered infection of the surgical site.

Of the five remaining patients, in one case it was impossible to confirm whether the patient had received the treatment with mupirocin correctly; this was a case of colonization by MSSA, so that the usual prophylaxis with cefazolin was applied. Although the treatment was confirmed in the other 4 cases, this was no so for the post-treatment culture. Three of these cases were found to be colonized by MSSA and received the usual treatment, and the other case of colonization by MRSA was treated prior to surgery with vancomycin and isolated from contact in the hospital ward until a negative swab was obtained.

One patient with a negative detection culture had an infection of the deep surgical site by S. epidermidis. This was treated by debridement, antibiotics and retention of the implant, with a good result.

Three patients in the historical cohort group suffered deep surgical site infection: one by S. epidermidis, which required debridement with retention of the implant and antibiotic therapy; one by E. cloacae, which was treated by exchange in 2 acts, with relapse of the infection and finally arthrodesis; lastly, there was one case of infection by MSSA S. aureus, which was resolved by revision surgery in 2 acts. One other case in the historical cohort suffered dehiscence of the wound that was resolved by debridement, with a positive culture for MSSA S. aureus, so that it was classified as a superficial infection. These findings were found to lack statistical significance by a Chi-squared test.

Respecting the economic analysis, considering that 312 patients were screened, of whom 19 positive patients were treated, with mupirocin treatment confirmed in 18 of them, and with a test after decolonization treatment in 14 patients before surgery, the cost of the programme amounted to €1661.85(312×4.66€+19×7.51€+14×€4.66).

On the other hand, the cost/effectiveness of detecting a S. aureus carrier amounts to €76.5(312×€4.66/19).

Inferring the intention to treat, including unscreened and lost patients, the cost of screening in the intervention group would have been 1831.38€ (393×4.66€), after which the cost of treatment and the follow-up culture would have to be added.

DiscussionThe S. aureus screening and decolonization programme screened 89% of the patients. 13% of the patients were found to be colonized with S. aureus, and the majority of these were confirmed to have been decolonized. None of the group of screened patients suffered surgical infection by S. aureus or any other germ. Compared with a historical cohort, infections of the prosthesis by any germ were reduced from three to one.

This study has limitations. The first of these refers to its design, as in studies of historical cohorts, errors due to confusion factors and distortions, such as the varying incidence of infections from one year to another, are more common than they are in prospective studies. The losses during follow-up amounted to 10.4%, without reaching the limit of 20% defined in the literature as a high rate of loss; moreover, the causes of loss of follow-up were the same in both groups.21 Although the follow-up time used of 90 days is the same as the one used in certain publications22,23 to evaluate infection, this criterion is also used to determine cases of re-hospitalization, and it may be suitable to increase the duration of follow-up to one or 2 years in a subsequent review. Lastly, the 2021 cohort was compared with the one in 2019 because of the major impact of the SARS-CoV-19 pandemic on the health system in 2020, so that it was impossible to implement follow-up protocols or gather data during that year for S. aureus colonization and other factors.

Although S. aureus screening and decolonization programmes are recommended in several protocols, this is usually optional.24–27 The reasons for this are the lack of high-level scientific evidence and the logistical difficulties of implementation.

Our hospital is located in a predominantly rural province and health catchment area, so that it has the challenge of covering a large area for medical care with a low population density, offering service to five regions with towns up to 65km away from the hospital. However, by using a protocol based on obtaining samples in different primary care health centres it was possible to screen 89% of the patients. This percentage is similar to the figures reported in other studies, which screened from 79%6 to even 91.8%.28

The prevalence of S. aureus carriers in the intervention group amounted to 13%, which is lower than the 30% reported in other series7,8 and the 20%–30% of the general population.10 Regarding methicillin resistance, eight cases of MRSA were reported, accounting for 42.1%, and 11 cases of MSSA at 57.9%. This rate differs from that in the series such as the one by Sousa et al.,6 which report 96.5% MSSA and 3.5% MRSA.

Colonized patients were treated with nasal mupirocin according to guidelines. This treatment has minimum side effects and there is long experience with using it. It was also associated with previous screening, so that treatment was selective and thereby reduce possible side effects and possible antibiotic resistance.28 There are other decolonization strategies, such as the routine treatment of all patients with mupirocin,7,22 although these may have negative repercussions in terms of costs and antibiotic resistance. Routine decolonization is also possible using pharmaceutical antiseptic agents, although these may have disadvantages such as difficulty in accessing and preparing them in all centres.29

After treatment it is important to confirm decolonization with a follow-up culture within the 3 weeks prior to surgery.11 This was achieved in our study in 74% of cases (14/19); no follow-up culture was obtained in the other cases. This datum is lower than those reported in other studies such as the one by Kalmeijer et al.,7 which reported 83.5% confirmation of decolonization.

The prevalence of infection of the prosthesis in the intervention group was 0.28%, while in the historical cohort it was 0.72%; these figures are lower than those reported in the literature.1,6 Furthermore, S. epidermidis was the micro-organism which caused the only infection in the intervention group, unlike S. aureus which is described in the literature in up to 60% of occasions,6,8 and in 33% of our historical cohort. The low rate of infection of the prosthesis which is reported, with a majority of infections by S. aureus, even in the historical cohort, means that a very high number of patients would be necessary to detect significant differences in terms of a reduction in infections after the application of the decolonization programme.

Therefore, and in spite of not achieving statistical significance in a Chi-squared test, the eradication of the status of being a S. aureus carrier by means of the treatment led to a lower incidence of infection in the surgical site, by S. aureus as well as other germs, in comparison with a historical cohort with statistically comparable basal characteristics. According to the literature, implementing S. aureus decolonization programmes may reduce infections of the prosthesis by all types of germs.11,23

With the variables that were used no factors which could be used to identify possible carriers were found. It therefore seems advisable to test all patients who are candidates for prosthetic surgery.

It may be asked whether these programmes could be recommended in general, or if a study on the incidence of S. aureus infection would be necessary in each individual hospital before applying decolonization protocols; this would have the purpose of identifying infection rates that justify the possible benefits of applying these protocols. In the case of hospitals with a low rate of prosthesis infections in general and more specifically by S. aureus, it could be asked whether the multidisciplinary effort and the difficulty of applying protocols of this type would justify their application.

Nevertheless, the authors consider that while a properly established protocol which is included in the clinical routine of patients, such as the one presented here, does not involve high logistical and economic costs, it does provide benefits.

There is discussion about the economic implications of programmes of this type.8,22,23,29,30 Their direct costs are easy to ascribe, although indirect costs must also be taken into account, as they may exist in the form of: the time spent by doctors and the multidisciplinary teams on designing and implementing the protocol, the time take by anaesthesia to check the patients and identify the ones who are positive so that they can be treated, and the time taken by the prevention team in checking those patients who had been positive, after they had received treatment to check the decolonization. In our case these costs were considered to be minimum, as the time taken to design protocols did not reduce the time spent by the group on providing care. Carriers were identified in the same pre-anaesthesia visit when other activities took place, and the prevention team undertook the follow-up during their usual work hours.

In the light of the calculated costs, the programme may be deduced to be economically viable, given that its direct costs amount to only €1661.85. Although the reduction in infections was not found to be statistically significant, the said costs may be considered to be far less than those arising from revision surgery of total knee arthroplasty ($24,027 in one act or $38,109 in 2 acts)3 or total hip arthroplasty (€31,133±9733 or €54,098±12,700 in 2 acts).4

ConclusionsThe implementation of a S. aureus screening and decolonization programme in primary prosthetic surgery of the hip and knee is useful in detecting and decolonizing patients who are colonized by S. aureus, with low costs and the advantage of selective treatment targeting. Implementing these programmes in the context of a protocol for the prevention of surgical infection by S. aureus or other germs avoids the impact of this on patient quality of life as well as in economic terms.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

FundingThis work was financed by the Orthopaedic and Traumatology Surgery department of the Hospital Universitario de Santa Maria, through the Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida, Fundació privada Dr. Pifarré.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Ethics CommitteeApproved by Comitè d’Ètica d’Investigació amb Medicaments, Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova Lleida Registration number: CEIC-2606.

The authors would like to thank the following professionals for their collaboration: Dr. Maria Fernanda Ramírez Hidalgo, for her help in revising the protocol; Dr. Laura Prats, for her collaboration in the revision of the final manuscript; Ms. Inés Ortíz Catalan, hospitalization nurse, Ms. Alba Guitard Quer, UTIN nurse, and Ms. Cristina Cortijo Lecina, surgical patient reception nurse, for their collaboration in data gathering.