Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is one of the main causes of hip pain in young adult and a contributory factor for development of early primary osteoarthritis. An accurate clinical diagnosis, supported by imaging studies, is important to determine the best treatment for the patient. The aim of this study is to determine the diagnostic correlation between direct magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arthrography and the arthroscopic findings.

Materials and methodA review was performed on a series of 36 patients diagnosed with FAI, and who underwent hip arthroscopy surgery between 2009 and 2012. All of them had a direct MRI arthrography performed in our hospital. The presence of labral lesions, CAM deformity, and acetabular and femoral cartilage damage, were evaluated in both imaging techniques.

ResultAfter analysing the results and taking the hip arthroscopy as ‘gold standard’, a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 77% were obtained, with a PPV of 87% for the diagnosis of labral lesions by direct MR arthrography. The specificity for CAM deformity was 100%, with a sensitivity of 79% and PPV of 100%. For chondral disorders lower values were found for both acetabulum and femoral head. For acetabular lesions the sensitivity was 78.5%, and specificity was 82% with a PPV of 73% and NPV of 80%. For femoral lesions, there was a sensitivity of 71.5%, a specificity of 73%, with a PPV of 62.5% and NPV of 80%.

ConclusionsDue to the high sensitivity for the detection of labral lesions and the high specificity to detect CAM deformity, hip MR arthrography is a useful diagnostic tool for femoroacetabular impingement.

El síndrome de atrapamiento femoroacetabular es una de las causas de coxalgia en el adulto joven; así mismo, es una entidad clínica que contribuye en la etiopatogenia de la coxartrosis en estos pacientes. Un diagnóstico clínico certero apoyado por las técnicas de imagen diagnósticas disponibles es fundamental para poder determinar el mejor tratamiento. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es determinar la correlación diagnóstica entre la artrorresonancia magnética directa y los hallazgos artroscópicos.

Material y métodoRevisamos una serie de 36 pacientes con diagnóstico de atrapamiento femoroacetabular intervenidos mediante artroscopia de cadera realizada entre 2009 y 2012 con estudio de artrorresonancia previo realizado en nuestro centro. Valoramos en ambos el hallazgo de lesiones labrales, deformidad tipo CAM femoral y lesiones condrales, tanto femorales como acetabulares.

ResultadoTomando los hallazgos de la artroscopia de cadera como el diagnóstico de certeza, calculamos una sensibilidad del 87% y una especificidad del 77% con un VPP del 87% para el diagnóstico de las lesiones labrales mediante artrorresonancia magnética directa, respectivamente. La especificidad para el diagnóstico de la deformidad tipo CAM femoral es del 100%, con una sensibilidad del 79% y un VPP del 100%. Para las lesiones condrales en acetábulo y cabeza femoral obtenemos valores más bajos, sensibilidad del 78.5%, especificidad del 82%, VPP del 73% y VPN del 80% para las acetabulares, sensibilidad del 71.5%, especificidad del 73%, VPP del 62.5% y VPN del 80% en las femorales.

ConclusionesDadas la alta sensibilidad para la detección de lesiones labrales y la alta especificidad para determinar la presencia de deformidad en giba, la artrorresonancia magnética directa de cadera supone una buena herramienta diagnóstica en el atrapamiento femoroacetabular.

Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI) is one of the main causes of hip pain. Due to advances in diagnostic techniques and research, and improved knowledge of the specific pathology of the hip, we have seen an increase in the diagnosis, and therefore, in the incidence of hip disorders. This, added to the increased physical demands of a young, active and essentially athletic population, has led to an incidence of up to 15% of FAI being detected.1 We also know that it is a dynamic disease which causes early osteoarthritis of the hip.2,3

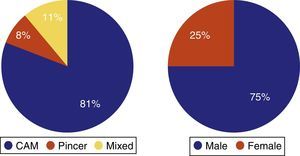

Three different types of impingement have been described according to the predominant morphology4: CAM, where the abnormality is in the femur (defect in the femoral cervico-cephalic transition); pincer, where the predominant deformity is in the acetabulum (overcoverage), and mixed, a combination of both.

A diagnosis of FAI starts with clinical suspicion when a young or middle-aged patient presents reporting unilateral or bilateral hip pain, related to posture or on effort, such as, for example, when playing sport, and to movements requiring maintained flexion of the hip.5 On physical examination we were able to observe reduced mobility of the hip (the greater the degree of osteoarthritis the greater the loss of mobility), a positive anterior impingement test (flexion at 90° and internal rotation) and a positive FABER's test (external flexion–abduction–rotation, position 4 of the affected leg) as clinical signs suggestive of a diagnosis of FAI.6 Labral and chondral lesions are difficult to determine with examination manoeuvres. Tijssen et al.7 conducted a revision of 21 studies, and concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend specific diagnostic clinical tests in order to confirm or rule out FAI with or without labral lesions or other associated alterations.

With regard to imaging tests; we identified bone alterations through simple radiology, anteroposterior projection of the hip and Dunn's axial projection.8 Subsequently, with a view to suggesting possible surgical treatment, we were able to obtain information on labral alterations using magnetic resonance arthrography.

Magnetic resonance arthrography has the advantage of being a simple test but the disadvantage is that it is minimally invasive and has associated risks.9 Therefore, it is important to be aware of its real clinical usefulness. Numerous studies have tried to define the usefulness of magnetic resonance arthrography in detecting these lesions, and have obtained very varied results.9–14

The objective of our study is to determine the diagnostic correlation between direct magnetic resonance arthrography and arthroscopic findings in patients with a probable diagnosis of FAI.

Materials and methodsWe undertook a retrospective revision of patients who were operated using arthroscopy of the hip in our centre between 2009 and 2012. Patients with a diagnosis of FAI and who had received magnetic resonance arthrography in our centre were included in the study.

Patients whose magnetic resonance imaging had not taken place in our centre, patients who had not been operated by ourselves or operated using open surgery, and patients who had undergone arthroscopy of the hip for reasons other than FAI syndrome were excluded from the study.

36 patients were included in the study, 27 were male and 9 female, with a mean age of 39 (27–53). A total of 22 right and 14 left hips were operated.

The main reason for consultation was groin and/or buttock pain occasionally defined as “C” shaped; pain which increased with hip flexion or after playing a sport. On occasion, pain with more mechanical characteristics was defined.

All of the patients were informed of the risks, limitations, complications and benefits of direct magnetic resonance arthrography.

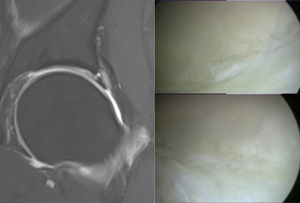

For the direct magnetic resonance arthrography, the hip was punctured in the superolateral portion in the femoral cervico-cephalic joint. Between 10cc and 12cc of a 0.5ml solution of gadolinium paramagnetic contrast (Gadovist®) dissolved in 20ml physiological saline was injected. Three-Tesla magnetic resonance (Trio, Siemens®) was used for the study in T1 sequences with fat saturation, T2 with fat saturation and 3D gradient echo on 4 spatial planes; coronal, sagittal, axial and oblique. The images obtained were interpreted by a team of 2 radiologists who were specialists in musculo-skeletal pathology.

We compared the findings observed during the intervention with those found in the previous direct magnetic resonance arthrography. In both we assessed the existence of labral lesions, CAM deformity in the femur, chondral lesions in the acetabulum and chondral lesions in the femoral head.

The hip arthroscopy was always performed by the same surgeon. The procedure was undertaken with the patient lying on their back on a traction table which enabled intraoperative decoaptation of the hip. The interventions were performed following the outside–inside technique described by Margalet. After locating the lesion, the acetabular labral edge was decorticated in order to repair the labral tear. Suturing was through anchors based on suture systems, generally 1.4mm thick. All the intra-operative findings and procedures undertaken during the intervention were noted in the operation notes.

With regard to the general details of the surgical procedure; the intervention was performed with the patient under general anaesthetic and orally intubated. General antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines were followed for all patients with 1g of intravenous cephazoline during induction of anaesthesia, completing the guidelines with 3 doses of 1g cephazoline every 8h in the post-operative period. All the patients had a urinary catheter which was removed the following day and they received antithrombotic prophylaxis with Hibor 3.500 UI. The day after surgery the patient got up, in order to initiate a gradual process of mobility using crutches, with total load bearing on the limb. They were hospitalised for around 2 days and discharged with a specific rehabilitation programme of 16 weeks to be followed in a specialist centre in their region. Follow-up of these patients consisted of a first review at 1.5 months after the operation and at 4 months (at the end of their rehabilitation programme). Thereafter the patients were seen annually, if progress had been satisfactory, otherwise they were assessed according to their individual needs.

We performed a sensitivity, specificity and PPV calculation to detect each lesion on the magnetic resonance arthrography taking the findings observed during the arthroscopic intervention as diagnostic certainty.

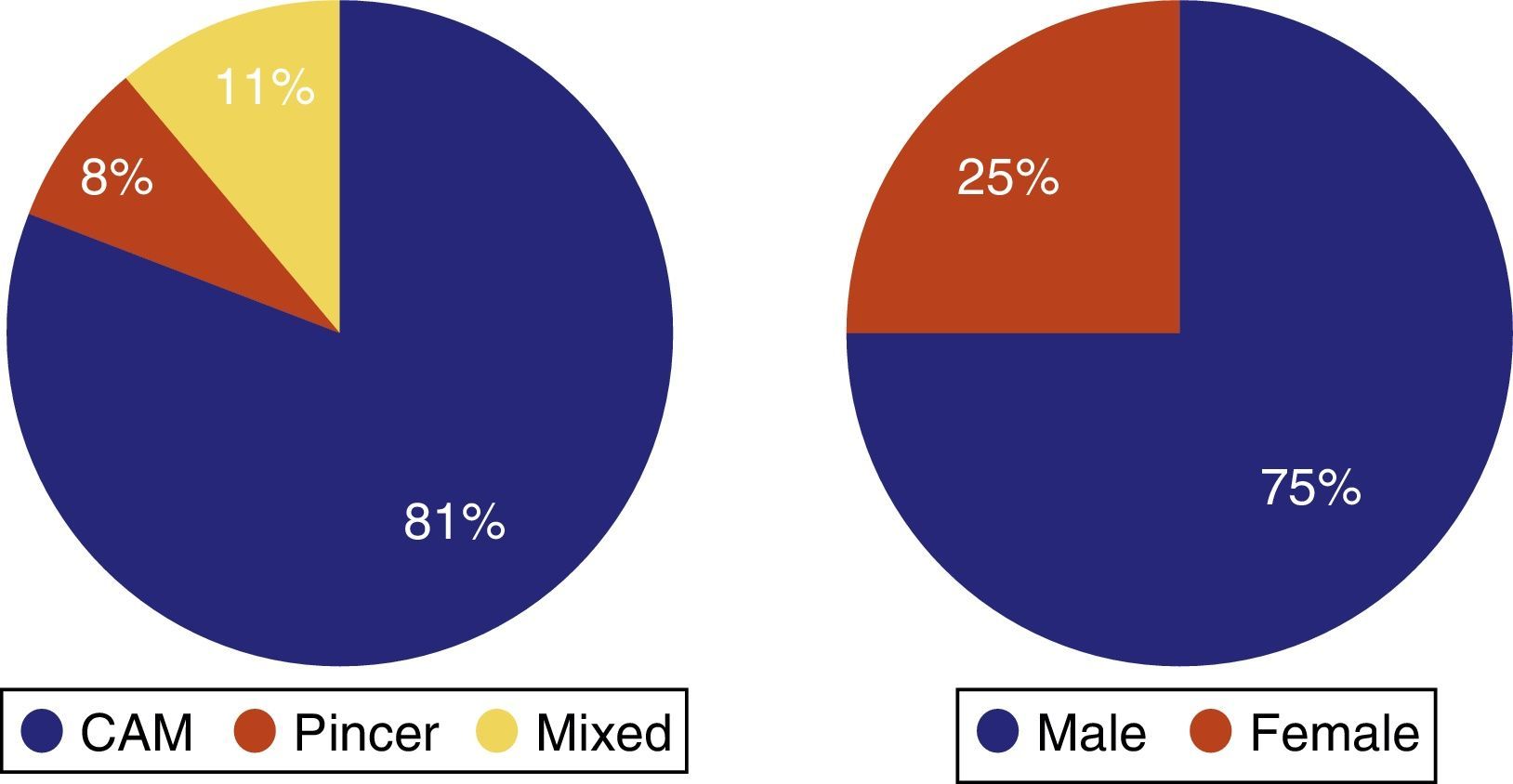

ResultsIn total, 36 patients met the inclusion criteria for our study, 27 men and 9 women with a mean age of 39 (27–53). Twenty-nine patients presented a CAM-type FAI, 3 pincer-type and 4 mixed (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

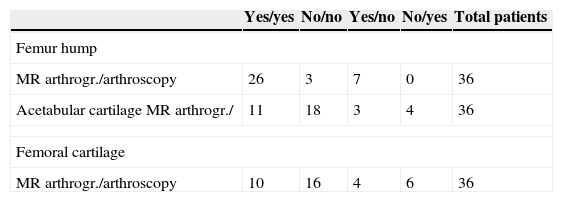

Demographic data, type of alteration and findings on magnetic resonance arthrography (MR arthrography) and arthroscopy.

| Yes/yes | No/no | Yes/no | No/yes | Total patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur hump | |||||

| MR arthrogr./arthroscopy | 26 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 36 |

| Acetabular cartilage MR arthrogr./ | 11 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 36 |

| Femoral cartilage | |||||

| MR arthrogr./arthroscopy | 10 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 36 |

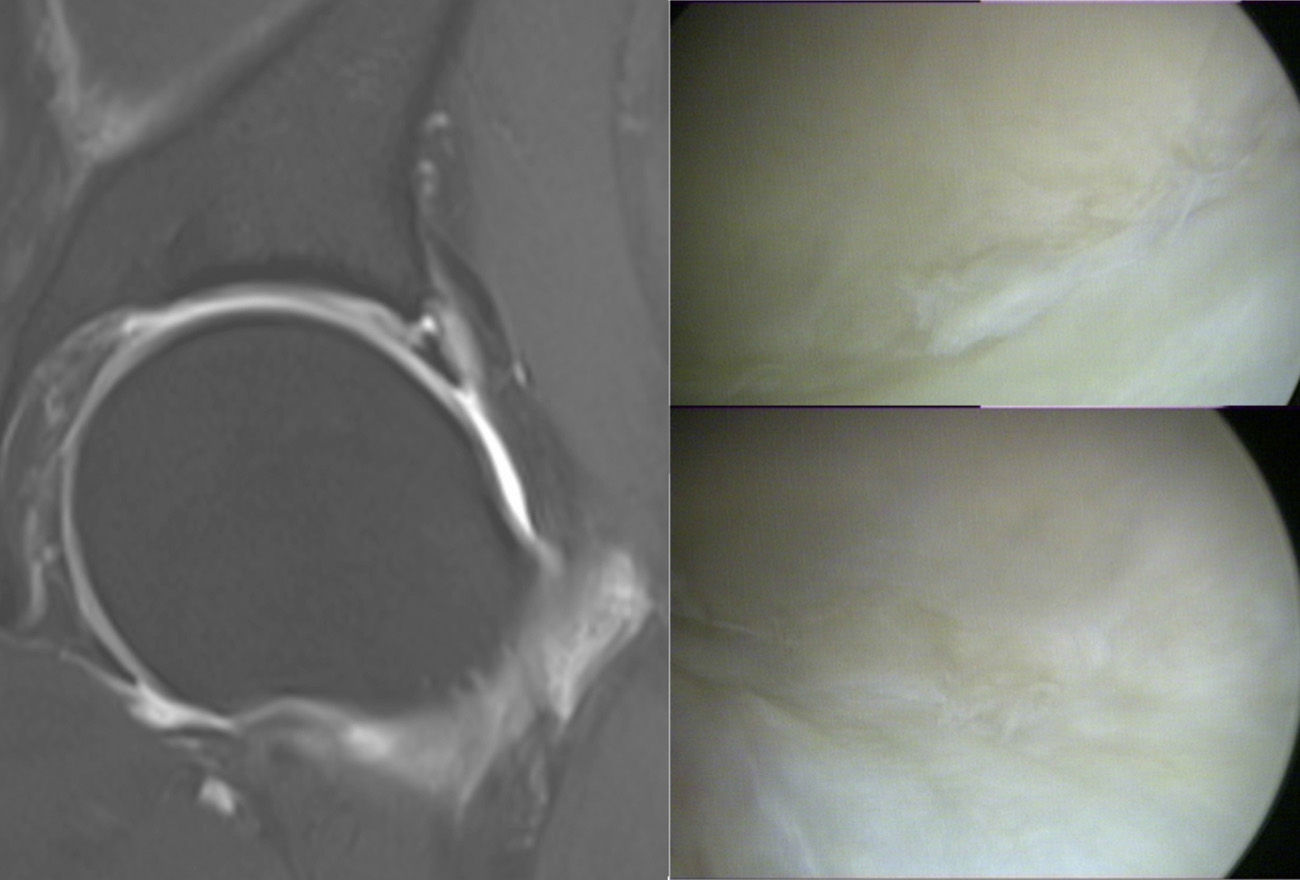

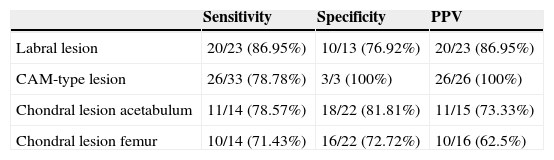

In our series we found 87% sensitivity, 77% specificity with a PPV of 87% for the diagnosis of labral lesions using magnetic resonance arthrography. With regard to the diagnosis of CAM-type femoral deformity, the specificity of magnetic resonance arthrography was 100% with a sensitivity of 79% and a PPV of 100%. For the chondral lesions we found lower values in both locations, acetabular and femoral. For chondral lesions of the acetabulum (Fig. 2,) sensitivity was 78.5%, whereas specificity was 82% and PPV was 73%. Sensitivity for lesions in femoral cartilage was 71.5%, specificity 73% and PPV 62.5% (Table 2).

Sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value for each type of lesion.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labral lesion | 20/23 (86.95%) | 10/13 (76.92%) | 20/23 (86.95%) |

| CAM-type lesion | 26/33 (78.78%) | 3/3 (100%) | 26/26 (100%) |

| Chondral lesion acetabulum | 11/14 (78.57%) | 18/22 (81.81%) | 11/15 (73.33%) |

| Chondral lesion femur | 10/14 (71.43%) | 16/22 (72.72%) | 10/16 (62.5%) |

Clinically, the patients evolved satisfactorily, resuming their usual physical activities with no discomfort. We should mention that 2 patients presented gluteal tendinitis and 1 patient psoas tendinitis. All these cases were resolved after a specific rehabilitation programme. With regard to complications in the immediate post-operative period; 2 patients had transitory hypoesthesia of the perineum which resolved spontaneously.

DiscussionOur results support performing prior direct magnetic resonance arthrography, due to its high sensitivity and specificity in detecting labral lesions, of articular cartilage and the presence of femoral hump-type deformity.

With regard to the detection of alterations in the acetabular labrum, the literature shows sensitivity between 100% and 81%.9–13 We obtained a sensitivity of 87%. And we also recorded a specificity of 77%, this value is somewhat higher compared to the high limit of the range covered in the literature, between 75% and 51%.9–13 To all of this we associated a PPV of 87%, which indicated to us the capacity of this test to detect alterations of the labrum with certainty when these alterations really exist. However, this result is to be expected as we had a sample with a high prevalence of the disease. PPVs of 99% and NPVs from 39% to 19% are observed in the literature,8–12 compared to the 77% obtained in our study. This tells us that it is likely that that patient did not have labral alterations when magnetic resonance arthrography gave a negative result for this. The clinical implication of these results would be, should hip arthroscopy be decided, that we are highly likely to find the lesion shown by magnetic resonance arthrography. This enables accurate and early treatment of FAI, preventing progression of the lesion and an increased therapeutic failure.

Despite the fact that the sensitivity and specificity values of magnetic resonance arthrography obtained are high, labral lesions exist which are not detected by resonance, in particular, the incipient lesions classified by Czerny et al.14 as stages 1A (alteration of signal but with no signs of detachment or break). Furthermore, there is also the possibility that a lesion is observed on magnetic resonance arthrography but the location described does not coincide with that found on arthroscopy.14

The literature with regard to chondral lesions jointly analyses the presence of cartilage damage in the acetabular or femoral area. We have differentiated according to the location of the lesions. However, the literature shows sensitivity values between 47% and 17%,9–13 specificities between 100% and 89%,9–13 PPV of 84%11 and NPV of 59%,11 for magnetic resonance arthrography in the detection of articular cartilage alterations. In our series, for lesions in acetabular cartilage we obtained a sensitivity of 78.5%, specificity of 82%, PPV of 73% and NPV of 80%. With regard to lesions in the femur, we found somewhat lower values; sensitivity of 71.5%, specificity of 73%, PPV of 62.5% and NPV of 80%.

In their recent study, McCarthy and Glassner,13 also assessed the existence of free intra-articular bodies; they conclude that magnetic resonance arthrography is useful in confirming their presence.

Our study presents some limitations. Given that the sample size is small and this is a retrospective study, the results need to be confirmed in a larger population with long-term follow-up. Secondly, we did not compare the results with a control group in whom there was no labral, chondral damage or CAM deformity. Furthermore, the resonance was interpreted by 2 radiologists who were musculo-skeletal specialists, which may lead to intero-observer variability when analysing the results. Moreover, we only assessed the existence or otherwise of a lesion, we did not classify or describe the lesion.15,16 This further supports the possibility of discrepancies between the radiologists themselves and between the radiologists and the surgeon.

Our results show high sensitivity in the detection of labral lesions, high specificity in determining the presence of femoral CAM deformity and moderate usefulness in diagnosing chondral lesions. Therefore, we consider that magnetic resonance arthrography is a valid diagnostic test and useful in diagnosing FAI syndrome. It enables associated lesions to be detected, as well as their degree and location, which is essential for correct therapeutic planning.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human beings and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: González Gil AB, Llombart Blanco R, Díaz de Rada P. Validez de la artrorresonancia magnética como herramienta diagnóstica en el síndrome de atrapamiento femoroacetabular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:281–286.