This study presents a systematic review of the literature on the etiology of superficial and invasive candidiasis in Mexico reported from 2005 to 2015. The data have shown that Candida albicans is the most prevalent species with an increasing tendency of the non-C. albicans Candida species, as reported in other countries. The use of phenotypical methods in the identification of the yeasts limits the identification at the species level, particularly in species that are part of complexes, this is important because the identification only at the genus level leads to inadequate treatment due to the different susceptibility to the antifungals among species. In addition, this finding reveals the need to implement in clinical laboratories the molecular methods for the correct identification of the species involved, and the antifungal susceptibility tests to prevent the etiological changes associated with a poor therapeutic management.

Este artículo presenta una revisión sistemática de la bibliografía sobre la etiología de las candidiasis superficiales e invasivas en México en los años 2005-2015. Los datos muestran que Candida albicans se sitúa en primer lugar, pero hay una tendencia al aumento de otras especies del género, como se reporta en otros países. El uso de métodos fenotípicos para la identificación de las levaduras limita la identificación de la especie, especialmente de aquellas que forman parte de complejos; esto es importante, ya que la identificación solo del género puede conducir a un tratamiento inadecuado por la diferente sensibilidad de las especies a los antifúngicos. Por ello es necesario implementar en los laboratorios clínicos los métodos moleculares necesarios para la completa identificación de las especies implicadas y las pruebas de sensibilidad a los antifúngicos, para evitar cambios etiológicos asociados con un manejo terapéutico inadecuado.

Over the past 30 years, the incidence of opportunistic fungal infections has increased significantly and consistently worldwide. These mycoses are caused by filamentous fungi and yeasts, most notably Aspergillus and Candida, respectively, which are the most frequent causative agents. However, Candida is the main cause of mycosis in the world, especially in neutropenic patients, patients with malignancies treated with immunosuppressants, patients undergoing surgery or organ transplantation, preterm infants, and HIV/AIDS patients.37,66 Of the different clinical forms of candidiasis, the invasive variety is a persistent public health problem. The incidence and mortality rates associated with this infectious disease have remained unchanged for more than a decade despite major advances in the field of antifungal therapy; this persistence leads to an increase in the costs of hospital care.

The genus Candida includes more than 200 species, of which Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, Candida guilliermondii [current name Meyerozyma guilliermondii (Wick.)],43Candida lusitaniae, Candida dubliniensis, Candida pelliculosa, Candida kefyr, Candida lipolytica, Candida famata [current name Debaryomyces hansenii (Zopf)],46Candida inconspicua, Candida rugosa and Candida norvegensis are recognized as human pathogens more frequently.75 Some of these species are found as commensals in humans but can become pathogenic as a result of alterations in their microenvironment or compromise of the host immune system, promoting proliferation of the fungus and producing endogenous candidiasis; by contrast, exogenous infections are transmitted through the hands of medical personnel or contaminated devices.36

C. albicans has been considered the predominant species found in bloodstream infections; however, in the last two decades, there has been a growing trend of infections caused by other species of the genus, such as C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. dubliniensis, C. kefyr, C. famata, C. lusitaniae, Candida lambica, Candida zeylanoides, Candida africana, and C. guilliermondii.11,57,61,62 In addition, within the C. parapsilosis complex, Candida metapsilosis and Candida orthopsilosis have been identified as infection-causing agents of superficial candidiasis; in the C. glabrata complex, Candida nivariensis and Candida bracariensis have been found in genital candidiasis.29,47 However, it has been reported that C. albicans is still the most frequently isolated species among the different forms of candidiasis.61–64

This increase in non-C. albicans Candida species is attributed to the indiscriminate use of antifungals and increased use of implanted medical devices, organ transplantation and broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy.7,17,20 The treatment of the infections caused by these species may be difficult due to the resistance to some antifungals. C. krusei (intrinsically resistant) and C. glabrata (dose-dependent)9 are resistant to fluconazole, one of the most recommended antifungals in the treatment of invasive candidiasis, followed by echinocandins, voriconazole and amphotericin B.42,48,59

The species C. albicans and C. parapsilosis are naturally susceptible to fluconazole; however, over time, the susceptibility of C. albicans to this antifungal agent has decreased, as observed in clinical isolates of C. albicans, subjected to prolonged treatment with azoles.54,57,59 In addition, the susceptibility of C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata to fluconazole has changed discreetly and varies depending on the geographic region.60,64,80 It is clear that no antifungal agent is exempt from the development of resistance, so it is essential that laboratories identify not only the genus, but the species of the clinical isolates of Candida, and consider performing in vitro susceptibility tests to guide the choice of treatment. The mortality attributable to invasive candidiasis remains high, mainly due to the delay in the administration of an appropriate antifungal therapy.61 Therefore, this work presents the etiology of superficial and invasive candidiasis in Mexico, as well as an overview of the antifungal susceptibility of Candida species.

A systematic review of the medical literature published from 2005 to 2015 was carried out to know the prevalence of the etiology of superficial and invasive candidiasis in Mexico, as well as the susceptibility of the Candida species to antifungals. To achieve this objective, the selection of relevant articles based on their title and abstracts was carried out. The information was searched in the following databases: PubMed, Medline and Google Scholar (January 2005 to December 2015). The searches were performed using words present in articles, key words according to the database consulted; and synonyms extracted from the databases and publications available in both English and Spanish. The articles reviewed were those which included studies carried out in Mexico on superficial or invasive candidiasis with the Candida isolates identified at the species level by phenotypical or genotypical methods. Studies carried out in other countries; studies that reported the identification of Candida only at the genus level or that did not report the number of the isolates of Candida identified at the species level were not included.

The prevalence of the Candida species was estimated based on the total number of isolates. The prevalence of each type of candidiasis (oral, genital, cutaneous, onychomycosis and invasive) was estimated considering the number of the patients with each type of infection and the total population.

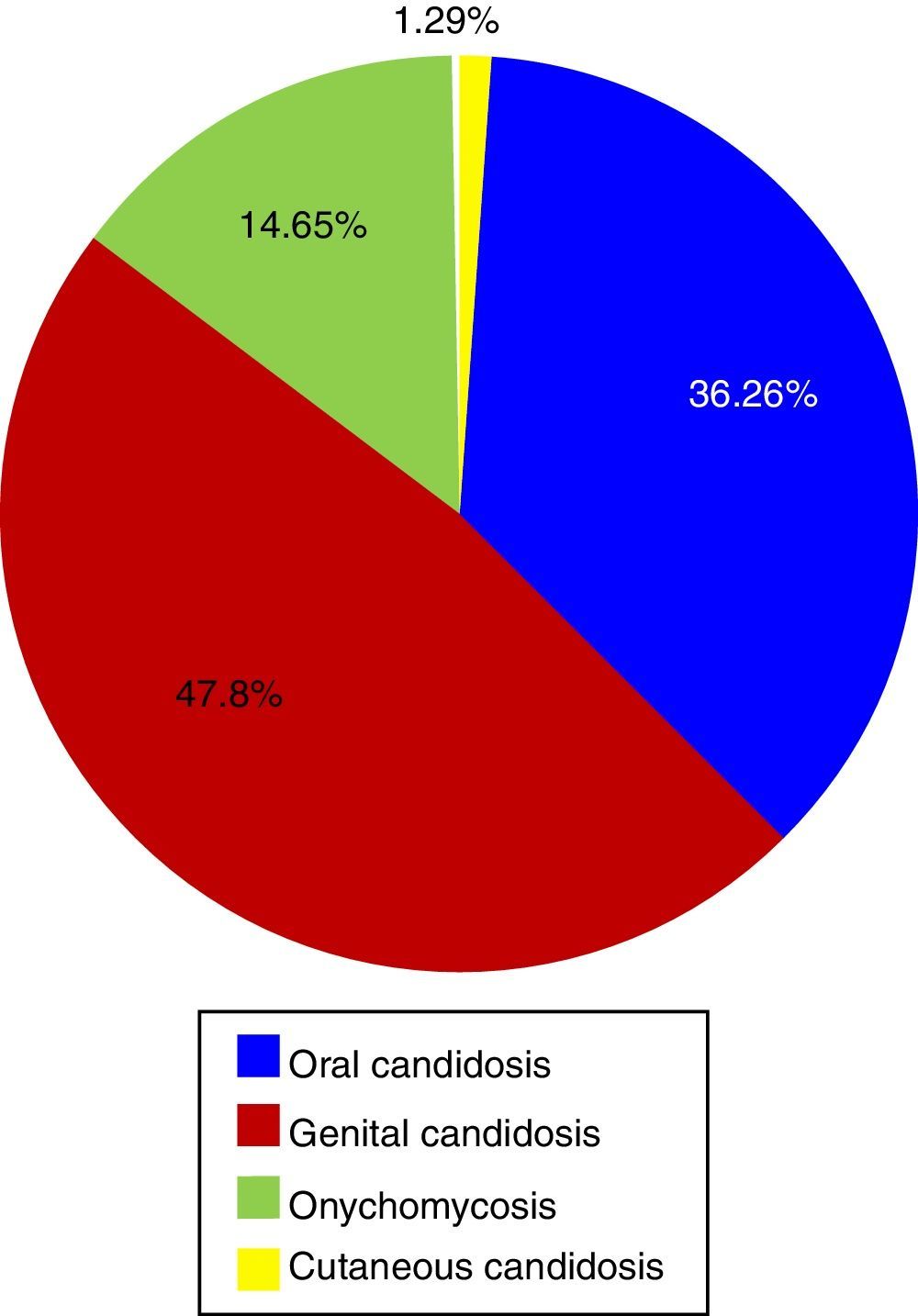

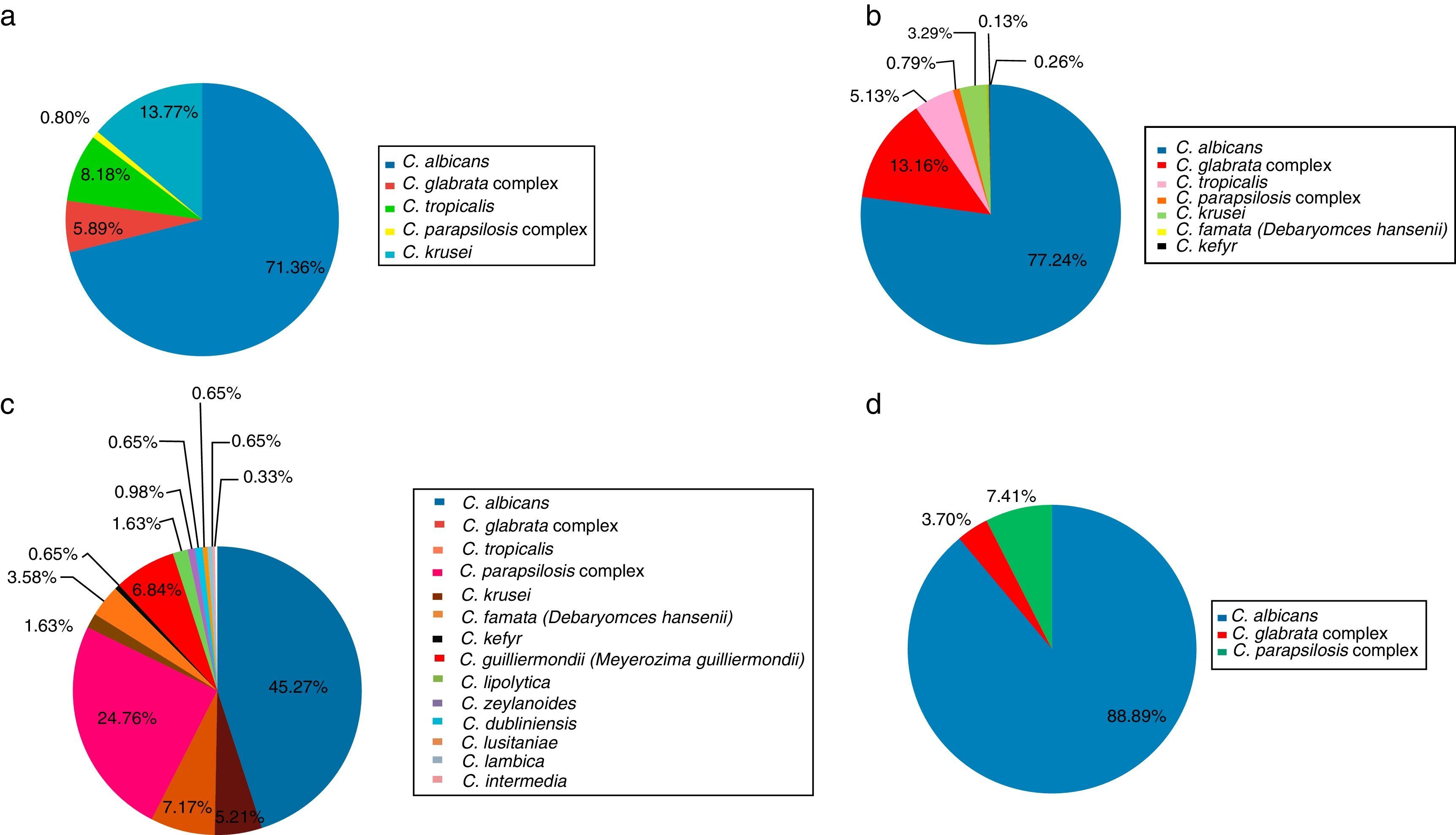

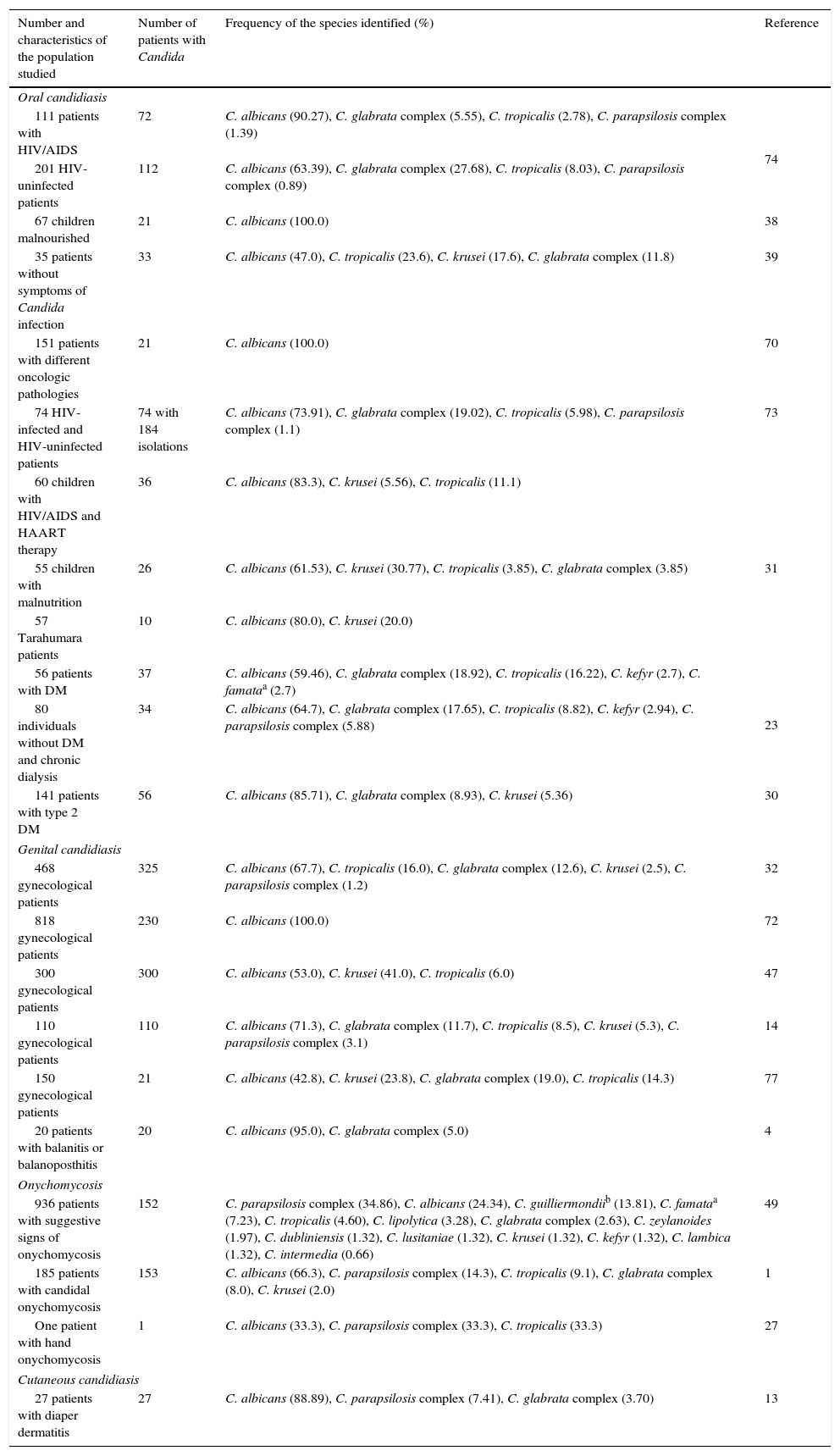

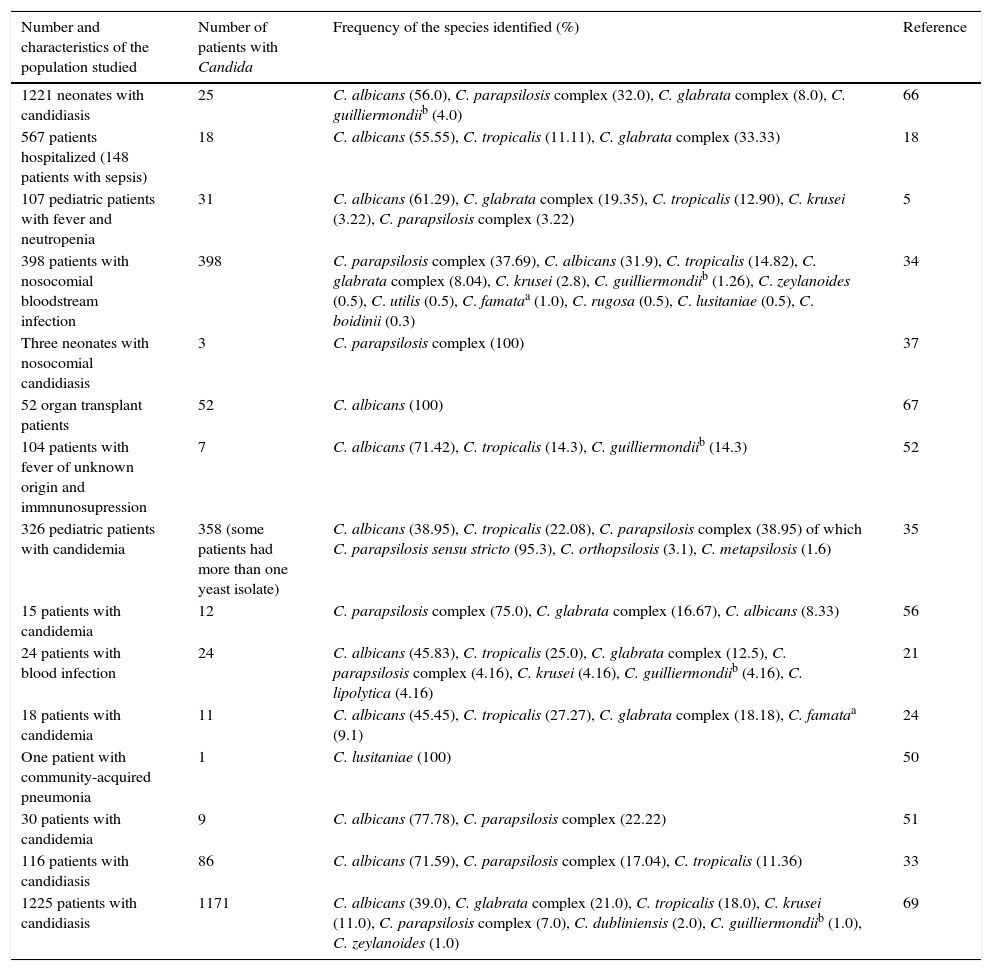

Etiology of superficial candidiasisTwenty-one articles on superficial candidiasis were found published between 2005 and 2015, of which 18 were selected based on the inclusion criteria. Two thousand and ninety six patients out of 4103 patients with suspected superficial candidiasis suffered this mycosis, representing 51.1%. The data found in the literature showed that, in terms of superficial candidiasis, the most common clinical form is the genital one (47.81%),32,47,72 followed by oral candidiasis (36.26%),23,30,31,38,39,70,73,74 onychomycosis (14.65%)1,27,49 and, finally, skin infections (1.29%)13 (Table 1 and Fig. 1). These data correspond to the states of Ciudad de México, Puebla, Yucatán, San Luis Potosí, Nuevo León and Veracruz. The reports of genital candidiasis showed that C. albicans was the most common cause (71.36%), followed by C. krusei (13.77%), C. tropicalis (8.18%), C. glabrata complex (5.89%) and C. parapsilosis complex (0.8%)4,14,32,47,70,77 (Table 1 and Fig. 2a). In 20 cases of balanitis and balanoposthitis, the most common etiologic agent was C. albicans, followed by C. glabrata complex. One case was reported as a mixed infection caused by C. albicans and C. glabrata complex.4

Distribution of Candida species associated with superficial mycosis in Mexico during the 2005–2015 period.

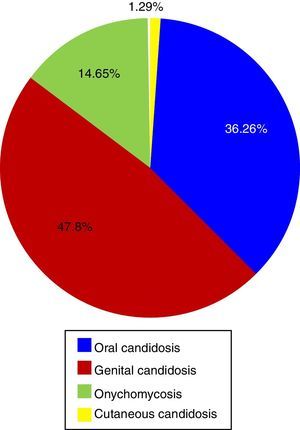

| Number and characteristics of the population studied | Number of patients with Candida | Frequency of the species identified (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral candidiasis | |||

| 111 patients with HIV/AIDS | 72 | C. albicans (90.27), C. glabrata complex (5.55), C. tropicalis (2.78), C. parapsilosis complex (1.39) | 74 |

| 201 HIV-uninfected patients | 112 | C. albicans (63.39), C. glabrata complex (27.68), C. tropicalis (8.03), C. parapsilosis complex (0.89) | |

| 67 children malnourished | 21 | C. albicans (100.0) | 38 |

| 35 patients without symptoms of Candida infection | 33 | C. albicans (47.0), C. tropicalis (23.6), C. krusei (17.6), C. glabrata complex (11.8) | 39 |

| 151 patients with different oncologic pathologies | 21 | C. albicans (100.0) | 70 |

| 74 HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients | 74 with 184 isolations | C. albicans (73.91), C. glabrata complex (19.02), C. tropicalis (5.98), C. parapsilosis complex (1.1) | 73 |

| 60 children with HIV/AIDS and HAART therapy | 36 | C. albicans (83.3), C. krusei (5.56), C. tropicalis (11.1) | 31 |

| 55 children with malnutrition | 26 | C. albicans (61.53), C. krusei (30.77), C. tropicalis (3.85), C. glabrata complex (3.85) | |

| 57 Tarahumara patients | 10 | C. albicans (80.0), C. krusei (20.0) | |

| 56 patients with DM | 37 | C. albicans (59.46), C. glabrata complex (18.92), C. tropicalis (16.22), C. kefyr (2.7), C. famataa (2.7) | 23 |

| 80 individuals without DM and chronic dialysis | 34 | C. albicans (64.7), C. glabrata complex (17.65), C. tropicalis (8.82), C. kefyr (2.94), C. parapsilosis complex (5.88) | |

| 141 patients with type 2 DM | 56 | C. albicans (85.71), C. glabrata complex (8.93), C. krusei (5.36) | 30 |

| Genital candidiasis | |||

| 468 gynecological patients | 325 | C. albicans (67.7), C. tropicalis (16.0), C. glabrata complex (12.6), C. krusei (2.5), C. parapsilosis complex (1.2) | 32 |

| 818 gynecological patients | 230 | C. albicans (100.0) | 72 |

| 300 gynecological patients | 300 | C. albicans (53.0), C. krusei (41.0), C. tropicalis (6.0) | 47 |

| 110 gynecological patients | 110 | C. albicans (71.3), C. glabrata complex (11.7), C. tropicalis (8.5), C. krusei (5.3), C. parapsilosis complex (3.1) | 14 |

| 150 gynecological patients | 21 | C. albicans (42.8), C. krusei (23.8), C. glabrata complex (19.0), C. tropicalis (14.3) | 77 |

| 20 patients with balanitis or balanoposthitis | 20 | C. albicans (95.0), C. glabrata complex (5.0) | 4 |

| Onychomycosis | |||

| 936 patients with suggestive signs of onychomycosis | 152 | C. parapsilosis complex (34.86), C. albicans (24.34), C. guilliermondiib (13.81), C. famataa (7.23), C. tropicalis (4.60), C. lipolytica (3.28), C. glabrata complex (2.63), C. zeylanoides (1.97), C. dubliniensis (1.32), C. lusitaniae (1.32), C. krusei (1.32), C. kefyr (1.32), C. lambica (1.32), C. intermedia (0.66) | 49 |

| 185 patients with candidal onychomycosis | 153 | C. albicans (66.3), C. parapsilosis complex (14.3), C. tropicalis (9.1), C. glabrata complex (8.0), C. krusei (2.0) | 1 |

| One patient with hand onychomycosis | 1 | C. albicans (33.3), C. parapsilosis complex (33.3), C. tropicalis (33.3) | 27 |

| Cutaneous candidiasis | |||

| 27 patients with diaper dermatitis | 27 | C. albicans (88.89), C. parapsilosis complex (7.41), C. glabrata complex (3.70) | 13 |

AIDS, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome; DM, diabetes mellitus; HAART, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

In oral candidiasis, the reports showed the effects on different populations,39,73 including HIV and non-HIV children and adolescents,31,74 patients with cancer,70 diabetics,23,30 malnourished children31,38 and people of the Tarahumara community.31 In this type of candidiasis, the most common etiologic agent was C. albicans (77.24%), followed by C. glabrata complex (13.16%), C. tropicalis (5.13%), C. krusei (3.29%), C. parapsilosis complex (0.79%), C. kefyr (0.26%), and C. famata (0.13%) (Table 1 and Fig. 2b).

In onychomycosis, the most common species in descending order were C. albicans (45.27%), C. parapsilosis complex (24.76%), C. tropicalis (7.17%), C. guilliermondii (6.84%), C. glabrata complex (5.21%), C. famata (3.58%), C. lipolytica (1.63%), C. krusei (1.63%), C. zeylanoides (0.98%), C. dubliniensis (0.65%), C. lusitaniae (0.65%), C. kefyr (0.65%), C. lambica (0.65%) and C. intermedia (0.33%) (Table 1 and Fig. 2c). Also, a case of a mixed infection caused by C. albicans, C. parapsilosis complex, and C. tropicalis was reported.27 Onychomycosis was mainly reported in the fingernails of adult women and was associated with diabetes, injuries, circulatory disorders, the use of corticosteroids and the use of fake nails,1,27,49 in agreement with the data reported by other countries.78C. parapsilosis complex predominated in toenails, while the most common fungus in fingernails was C. albicans.49

Regarding cutaneous candidiasis, only diaper rash reports were found during the period 2005–2015, where C. albicans was the most frequent species (88.89%), followed by C. parapsilosis complex (7.41%) and C. glabrata complex (3.70%)13 (Table 1 and Fig. 2d).

In superficial candidiasis, the Candida isolates were identified by conventional methods: culture,1,4,13,14,23,32,72,74 KOH (10–20%) test,1,4,13,14,27,49 germ tube,1,39,70,73,74 API 20C1,13,14,23,32,74 and ID3249,73 systems, CHROMagar4,13,27,30,31,38,39,47,49,70,73,77 chlamydoconidia formation,1,14,49,73 and growth at 45°C.49

Susceptibility to antifungal agents in superficial candidiasisThere are few studies on superficial candidiasis where antifungal susceptibility data are reported. The determination of the susceptibility to antifungals was performed using the reference procedures of broth microdilution (M27-A2 of the CLSI)32,49 and disc diffusion method (M44-A),73 as well as commercial systems such as Sensi-Disk,32 and Fungitest®,74 which produce results that, in general, correlate with the reference procedures.22 Based on these data, in general, oral candidiasis species showed <11% resistance to azoles.73,74 In vaginal candidiasis, C. glabrata showed >50% resistance to fluconazole.32 In onychomycosis, low resistance to azoles was reported in C. albicans and C. parapsilosis complex, high resistance to itraconazole was reported in C. guilliermondii and C. famata, and resistance was also reported to ketoconazole, itraconazole and fluconazole in four C. glabrata complex isolates.49 In cutaneous candidiasis, susceptibility to 2% sertaconazole was reported in C. albicans, C. parapsilosis complex and C. glabrata complex.13

Etiology of invasive candidiasisRegarding invasive candidiasis, 15 publications reported 2184 cases (Table 2). The affected populations included neonates56,66 and pediatric patients,35,51 transplant patients,52,67 patients with fever of unknown origin,24,51,52 patients with neutropenia,5 patients with a bloodstream infection,21,24,34,35,37,51,56 patients in intensive care units18,24,37,51,56,66 and patients hospitalized in hematology unit,24,52 infectious unit, internal medicine,24,51,52,56 rheumatology,52 emergency,56 neurosurgery,24 neurology,24 pulmonology units,24 and other patients hospitalized in non-specified services.21,33,34,50,69 The reports found were from Nuevo León, Guadalajara, Durango, Morelia, Sonora, Sinaloa, Coahuila, Estado de México, Ciudad de México, and Tamaulipas.

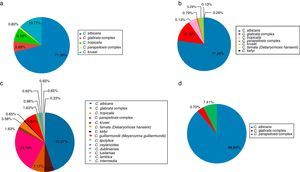

Distribution of Candida species associated with invasive infection in Mexico during 2005–2015 period.

| Number and characteristics of the population studied | Number of patients with Candida | Frequency of the species identified (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1221 neonates with candidiasis | 25 | C. albicans (56.0), C. parapsilosis complex (32.0), C. glabrata complex (8.0), C. guilliermondiib (4.0) | 66 |

| 567 patients hospitalized (148 patients with sepsis) | 18 | C. albicans (55.55), C. tropicalis (11.11), C. glabrata complex (33.33) | 18 |

| 107 pediatric patients with fever and neutropenia | 31 | C. albicans (61.29), C. glabrata complex (19.35), C. tropicalis (12.90), C. krusei (3.22), C. parapsilosis complex (3.22) | 5 |

| 398 patients with nosocomial bloodstream infection | 398 | C. parapsilosis complex (37.69), C. albicans (31.9), C. tropicalis (14.82), C. glabrata complex (8.04), C. krusei (2.8), C. guilliermondiib (1.26), C. zeylanoides (0.5), C. utilis (0.5), C. famataa (1.0), C. rugosa (0.5), C. lusitaniae (0.5), C. boidinii (0.3) | 34 |

| Three neonates with nosocomial candidiasis | 3 | C. parapsilosis complex (100) | 37 |

| 52 organ transplant patients | 52 | C. albicans (100) | 67 |

| 104 patients with fever of unknown origin and immnunosupression | 7 | C. albicans (71.42), C. tropicalis (14.3), C. guilliermondiib (14.3) | 52 |

| 326 pediatric patients with candidemia | 358 (some patients had more than one yeast isolate) | C. albicans (38.95), C. tropicalis (22.08), C. parapsilosis complex (38.95) of which C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (95.3), C. orthopsilosis (3.1), C. metapsilosis (1.6) | 35 |

| 15 patients with candidemia | 12 | C. parapsilosis complex (75.0), C. glabrata complex (16.67), C. albicans (8.33) | 56 |

| 24 patients with blood infection | 24 | C. albicans (45.83), C. tropicalis (25.0), C. glabrata complex (12.5), C. parapsilosis complex (4.16), C. krusei (4.16), C. guilliermondiib (4.16), C. lipolytica (4.16) | 21 |

| 18 patients with candidemia | 11 | C. albicans (45.45), C. tropicalis (27.27), C. glabrata complex (18.18), C. famataa (9.1) | 24 |

| One patient with community-acquired pneumonia | 1 | C. lusitaniae (100) | 50 |

| 30 patients with candidemia | 9 | C. albicans (77.78), C. parapsilosis complex (22.22) | 51 |

| 116 patients with candidiasis | 86 | C. albicans (71.59), C. parapsilosis complex (17.04), C. tropicalis (11.36) | 33 |

| 1225 patients with candidiasis | 1171 | C. albicans (39.0), C. glabrata complex (21.0), C. tropicalis (18.0), C. krusei (11.0), C. parapsilosis complex (7.0), C. dubliniensis (2.0), C. guilliermondiib (1.0), C. zeylanoides (1.0) | 69 |

aCurrent name: Debaryomyces hansenii (Zopf).48

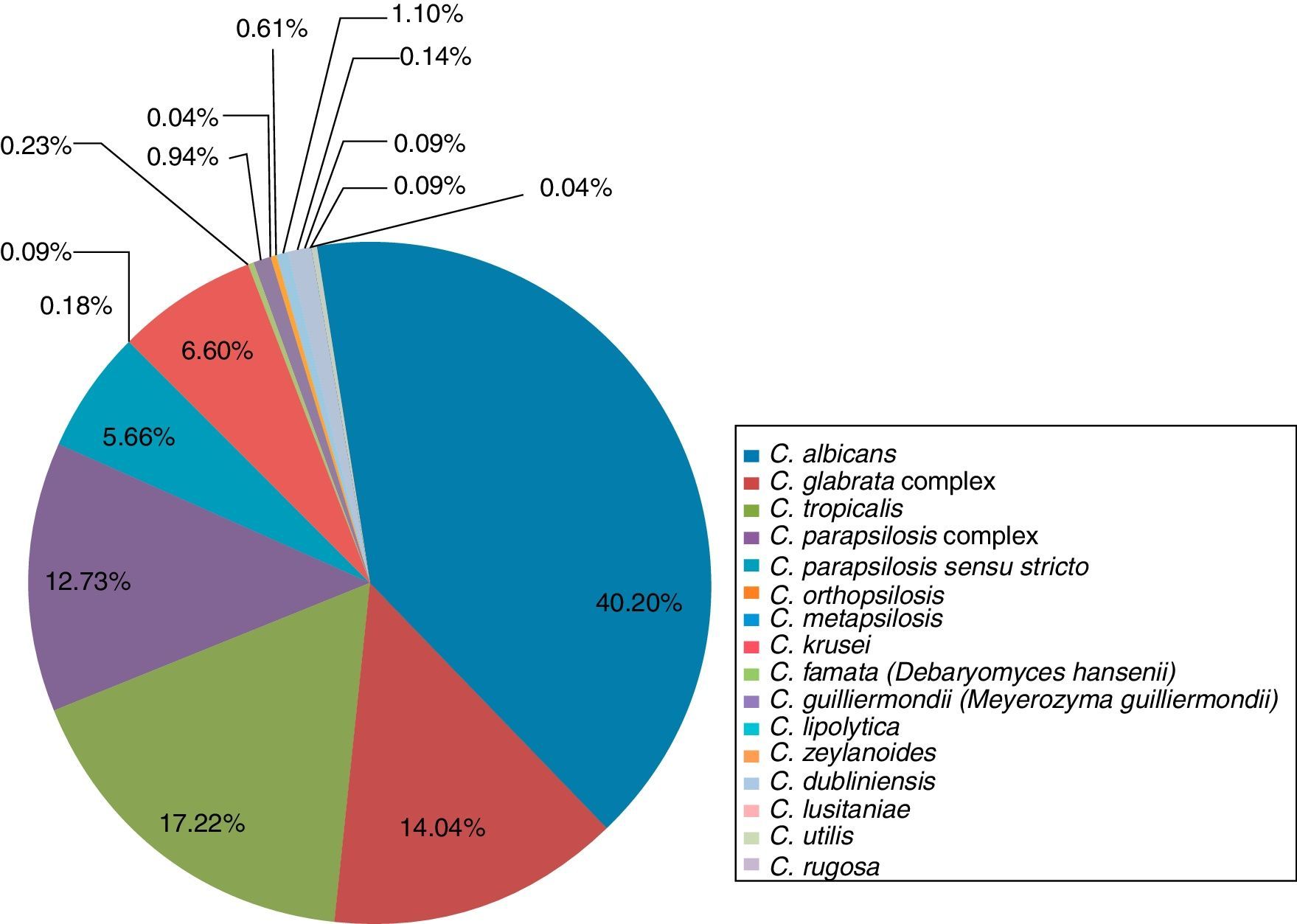

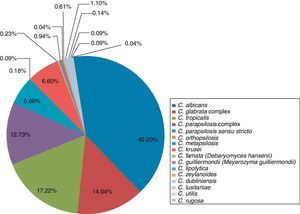

The main species associated with invasive candidiasis were C. albicans (40.2%), C. tropicalis (17.22%), C. glabrata complex (14.04%), C. parapsilosis complex (12.73%), C. krusei (6.6%), C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (5.66%), C. guilliermondii (0.94%), C. zeylanoides (0.61%), C. famata (0.23%), C. orthopsilosis (0.18%), C. lusitaniae (0.14%), Candida utilis (0.09%), C. metapsilosis (0.09%), C. rugosa (0.09%), C. lipolytica (0.04%), and Candida boidinii (0.04%)5,18,21,24,33–35,37,50–52,56,66,67,69 (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

In invasive candidiasis, Candida isolates were identified by conventional and molecular methods: culture,5,18,21,24,34,37,50,51,56,66,67,69 KOH (10–20%) test,52,69 germ tube production,5,21,35,69 API 20C,5,34,35,52,69 chlamydoconidia formation,33,35,52,69 CHROMagar,33,50,51,56,69 MicroScan33,37,51 and Vitek YBC21 automated systems, PCR,5,35 and RFLP.50

Susceptibility to antifungal agents in invasive candidiasisOf the 15 studies found in the literature on invasive candidiasis, only six21,24,34,35,50,56 included reports on antifungal susceptibility tests showing resistance to itraconazole in C. tropicalis, and to amphotericin B, fluconazole and itraconazole in C. glabrata complex.24,34,35,50 Susceptibility tests to antifungals were performed using the broth microdilution (M27-A234 and M27-A321,35,56 of the CLSI) reference procedures and the Fungitest® commercial test.50

DiscussionCandida is the main causative agent of mycosis in humans, but the epidemiology of candidiasis varies according to the geographical region.8,16,81 For this reason, it is important to conduct studies to determine the incidence of mycosis, the distribution of causative species, and their antifungal susceptibility profiles.

In Mexico, according to the morbidity yearbook published by the General Epidemiology Directorate (Dirección General de Epidemiología – http://www.epidemiologia.salud.gob.mx/anuario/html/morbilidad_nacional.html), urogenital candidiasis has remained among the 20 leading causes of illness nationwide, ranked between the 11th and 15th places. This is the only mycosis registered in the yearbook from 1988 to date. However, these data do not agree with the findings of the literature review, in which besides genital candidiasis other clinical forms of superficial candidiasis are also frequent. This discrepancy is due to the fact that fungal infections are not notifiable diseases. The results of this review also show that, between 2005 and 2015, the number of reports of superficial candidiasis was higher (18 publications) than that of invasive candidiasis (15 publications). The size of the population with suspected superficial candidiasis was 4103, with a positive frequency of 51.1%. In invasive candidiasis the suspected population suffering it was 4387 patients with a positivity of 49.8%. These data reveal that, in Mexico, the prevalence of superficial candidiasis is slightly greater than that of the invasive one, probably because factors predisposing to the superficial form (humidity, inadequate hygiene, pediatric age, pregnancy, hypothyroidism and type 2 diabetes mellitus) are more frequent than those predisposing to the invasive form.3 It is important to mention that, in Mexico, type 2 diabetes is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases (http://www.epidemiologia.salud.gob.mx/anuario/html/morbilidad_nacional.html), which may be one of the most important predisposing factors to acquire superficial candidiasis compared with predisposing factors such as neutropenia, central parenteral nutrition, central venous catheter use, abdominal surgery, broad-spectrum antimicrobial use and severe immunocompromise.79 This may also be due to, as in other countries, the incidence of invasive candidiasis being stable or decreased at certain institutions58 or to a greater interest in invasive candidiasis because of the more frequent mortality.

Regarding the etiology of superficial candidiasis, especially the oral form, there is agreement within the international scientific literature, which reports C. albicans as the predominant species, followed in a different order, depending on the clinical form, by C. krusei, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis complex. In contrast, other species such as C. kefyr and C. famata are rare.65 Among the patients with oral candidiasis, there is a greater prevalence of C. albicans in those with HIV/AIDS than in those without HIV/AIDS.31,74

In vaginal candidiasis, the diversity of species reported in Mexico was low as only C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. glabrata complex and C. parapsilosis complex have been reported; however, in other countries, and during the same period, C. dubliniensis, C. famata, C. lusitaniae, C. africana, C. guilliermondii, C. lambica, C. kefyr, C. zeylanoides, C. nivariensis and C. bracariensis were reported.44,76 In balanitis and balanoposthitis, C. albicans and C. glabrata complex were found as causative agents, but these data cannot be compared because there are no studies on the distribution of Candida species in these mycoses. They are considered sexually transmitted diseases; therefore, it is thought that their distribution must be similar to that of vaginal candidiasis.2

For onychomycosis, we found that C. parapsilosis complex is the most frequently isolated yeast, and C. albicans is ranked third. The diversity of species isolated in Mexico is higher; in other countries, up to four species have been reported40 and in Mexico, up to 14 species have been isolated.48 This may be due to the geographical variation in the distribution of species.78 In cutaneous candidiasis (diaper rash), we also noted that C. albicans is the most prevalent species,13 as in other parts of the world.55

The etiological diversity of invasive candidiasis in Mexico coincide with that in reports from other countries, where C. albicans, C. glabrata complex, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, and C. parapsilosis complex cause more than 90% of cases; the isolation of C. guilliermondii, C. lipolytica, C. famata, C. zeylanoides, C. utilis, C. rugosa, and C. boidinii is rare.7,16

Thus, a review of the studies conducted in Mexico shows that the etiology of candidiasis in our environment is similar to that of other countries, where C. albicans remains the most isolated species, both in surface and invasive infections, but other species of the genus are becoming more frequent. The phenotypic methods used in the identification of Candida species were direct examination to observe the micromorphology, filamentation on serum to discriminate C. albicans from other species, culture in CHROMagar Candida to visualize the use of chromogenic substrates characteristic of C. albicans, C. tropicalis and C. krusei, production and clustering of chlamydoconidia to differentiate C. albicans from C. dubliniensis, and biochemical tests using the VITEK 2, API 20C, or API 32C systems. In most cases, these methods do not allow to achieve the correct identification of the species, especially in the case of infrequently isolated yeasts and those forming species complexes. For example, with filamentation on serum, other species, in addition to C. albicans, can also produce germ tubes.41 In the case of CHROMagar Candida, which is one of the most widely used methods in clinical laboratories, there have been reports indicating that the color intensity of the colonies is not restrictive for C. albicans and C. dubliniensis species. In addition, it has been observed that the color of the colonies is gradually lost with subculturing or storage of the strains,28 leading to misidentifications. However, it has been demonstrated that systems designed to identify multiple species (VITEK 2, API 20C and API 32C) are less accurate for the classification of unusual species, as reported by Desnos-Ollivier et al.26 These investigators found that several isolates identified by API 32C as C. famata corresponded to C. guilliermondii, Candida haemulonii, C. lusitaniae and Candida palmioleophila, according to sequence analysis of gene segments. C. parapsilosis was also erroneously identified as C. famata with this method.15 Another disadvantage of these identification systems is that they fail to discriminate species with similar biochemical profiles that are genetically distinct, as in the case of the species complexes C. glabrata sensu stricto, C. nivariensis and C. bracariensis; C. parapsilosis sensu stricto, C. metapsilosis and C.orthopsilosis; and C. guilliermondii sensu stricto, Candida fermentati, Candida carpophila and Candida xestobii, which can only be differentiated by molecular methods.29,44 Due to the clinical importance of identifying the species of Candida involved, several researchers have proposed the use of molecular techniques. These include RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA),80 PCR-RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism)53 and AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism),6 PCR amplification of segments of specific genes, such as MP,63 which encodes a mannoprotein of 65kDa associated with morphogenesis and pathogenicity in Candida,12 pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE),45 sequencing of ITS (internal transcribed spacer) regions25 and microsatellites71 and multilocus sequence typing (MLST).68 These techniques have been widely used in phylogenetic, taxonomic, and population structure studies and are particularly useful for the delimitation of Candida species.19 However, the sequencing of ITS rDNA regions is the most widely used marker for the rapid, accurate identification of Candida species.25 The importance of discriminating the species within a complex is that they differ in their susceptibility to antifungal agents, virulence and biofilm formation, so it is important for clinical laboratories to conduct antifungal susceptibility tests to administer the proper treatment. However, this review found that only 33.3% of the selected publications show antifungal susceptibility results,13,21,24,32,34,35,49,50,56,73,74 which is a reflection that these tests are not routinely performed. This situation represents an additional problem to the lack of specific identification methods because antifungal resistance may depend on the Candida species; thus, it is essential to perform this identification for the proper management of the patients. However, in the few reports that were found, we observed that C. glabrata complex showed higher resistance to azoles and amphotericin B in cases of both superficial and invasive mycosis.32,34,49,56,74 This information is relevant because C.glabrata complex is one of the most common species in all forms of candidiasis. In addition, because discrimination between the members of C. glabrata complex is not reported, it is likely that a portion of the resistant isolates correspond to C. nivariensis.10

It is worth noting that the available epidemiological data in Mexico is limited, and the publications found corresponding to the 2005–2015 period only reflect the situation in the larger states of the country. However, these data facilitate predictions of what may be occurring in other states.

ConclusionsThe etiological behavior of candidiasis in Mexico is similar to that in other countries. However, it is important that both molecular tests for the accurate identification of yeasts and antifungal susceptibility tests are implemented and used routinely in healthcare facilities to ensure a specific diagnosis and the selection of appropriate therapeutic strategies. In addition, this strategy may help to prevent changes in the etiology of candidiasis as a result of the improper use of antifungals.

Authors’ contributionsMGFDL, MRRM, EDE, EMH, and GAA performed literature research and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This project was supported by the CONACYT – PDCPN2013-01 (216112).