Tinea capitis is an infection of the hair due to keratinophilic fungi, known as dermatophytes. Although the disease is common in children, several studies have also shown that it is far from unusual in adults, especially in post-menopausal women and immunocompromised persons.

AimsTo determine the incidence of tinea capitis in adults in our area, as well as the predisposing factors (gender, immunity), and causative species.

Materials and methodsA retrospective study was conducted over a period of 17 years, from 1995 to 2011, collecting data on cases of tinea capitis diagnosed in our dermatology department. Information collected for all patients included age, gender, location of the lesions, results of direct examination and culture, immune status, cause of immunosuppression, and the prescribed treatment.

ResultsThirty-three cases (11.4%) out of 289 cases of tinea capitis occurred in adults. Most of these adults (72%) were immunocompetent, and the rest were immunocompromised for different reasons. Three of the patients were men and 30 women, with 70% of the latter being post-menopausal. Trichophyton species were isolated in 76% of these adult patients, with Trichophyton violaceum being the most common. Treatment with oral terbinafine was successful in all these cases. Microsporum species were responsible for the other cases, all treated successfully with oral griseofulvin.

ConclusionsThis series of tinea capitis in adults is one of the largest to date. It shows that tinea capitis is not uncommon among the immunocompetent adult population. In our geographical area, except for prepubescent patients, most cases affecting the adult population were caused by species of the genus Trichophyton. In these cases the treatment of choice was oral terbinafine, which considerably shortened the treatment time, and was associated with fewer side effects than the classical griseofulvin.

Tinea capitis es una infección del pelo producida por hongos queratinofílicos llamados dermatofitos. Aunque la enfermedad es más común en niños, varios estudios han demostrado que no es infrecuente en adultos, especialmente en mujeres posmenopáusicas y personas inmunodeprimidas.

ObjetivoDeterminar la incidencia de tinea capitis en adultos de nuestra área, así como los factores predisponentes (inmunidad, género) y agentes causales.

MétodosLlevamos a cabo un estudio retrospectivo de un periodo de 17 años, desde 1995 a 2012, seleccionando casos de tinea capitis diagnosticados en nuestro departamento de Dermatología. Se recogió información clínico-demográfica de los pacientes que incluyó edad, sexo, localización de las lesiones, resultados de examen directo y cultivos, inmunidad, causa de la inmunosupresión y tratamiento.

ResultadosDe los 289 casos de tinea capitis, 33 (11,4%) eran de pacientes adultos. La mayoría (72%) fueron inmunocompetentes; la inmunodepresión en el resto de los casos era por diferentes causas. Tres de los pacientes eran hombres y 30 mujeres, la mayoría de las cuales eran posmenopáusicas (70%). Las especies de Trichophyton fueron aisladas en el 76% de los casos, con Trichophyton violaceum como el dermatofito más común; el tratamiento con terbinafina oral fue exitoso en todos los casos. Las especies microspóricas fueron responsables de los casos restantes y tuvieron una buena evolución con griseofulvina.

ConclusionesEsta serie de tinea capitis del adulto es una de las más largas hasta la fecha. Se demuestra que tinea capitis no es infrecuente entre la población adulta inmunocompetente. En nuestra área geográfica, salvo en prepúberes, la mayoría de los casos de tinea capitis de adultos son debidos a especies del género Trichophyton. En estos casos el tratamiento de elección fue la terbinafina oral, que acorta considerablemente la duración de tratamiento y se asocia a menos efectos secundarios que la clásica griseofulvina.

Tinea capitis is a hair infection due to keratinophilic fungi known as dermatophytes.3 Although taxonomically these fungi belong to the phylum Ascomycota, given that most of them are mitosporic, with not known sexual state, the name of their anamorphs in the genera Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton is commonly used in medical literature. Only the first two have species able to invade the terminal hair and, therefore, cause scalp ringworm. The most common dermatophytes isolated in adult tinea capitis include Trichophyton tonsurans, Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum.10

Although tinea capitis is common in children,8,20 several studies have shown that it is far from being rare in adults,3–7,9–11,19,21 particularly in postmenopausal women and immunocompromised persons; e.g., AIDS patients, transplant recipients, or people receiving high-dose steroid therapy. Adult tinea capitis may have polymorphic and atypical clinical presentations, leading to difficulty in diagnosis and a delay in treatment.

Materials and methodsWe undertook a retrospective study over a period of 17 years, from 1995 to 2011, of all cases of tinea capitis diagnosed in our dermatology department. The clinical diagnosis was confirmed in all the patients by direct examination using KOH and culture in Sabouraud-chloramphenicol, with and without cycloheximide. The sample was incubated at 27°C for 2 weeks. Cultures without evident fungal growth were kept for another 3 weeks before being considered negative. The mycological diagnosis was made after studying the macro- and micromorphological characteristics of the colonies, with the aid, if necessary, of specific tests. Data concerning age, gender, location of lesion, results of direct examination and culture, immune status, cause of immunosuppression, and any treatment given were collected in all patients.

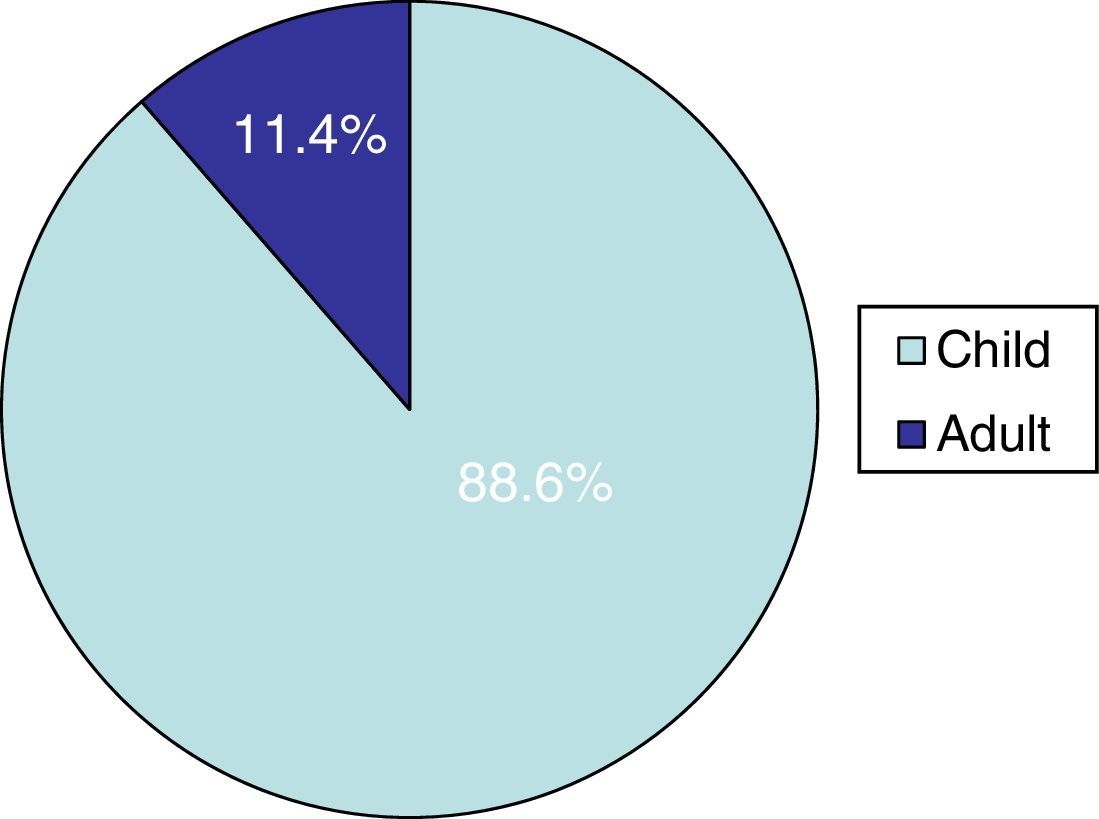

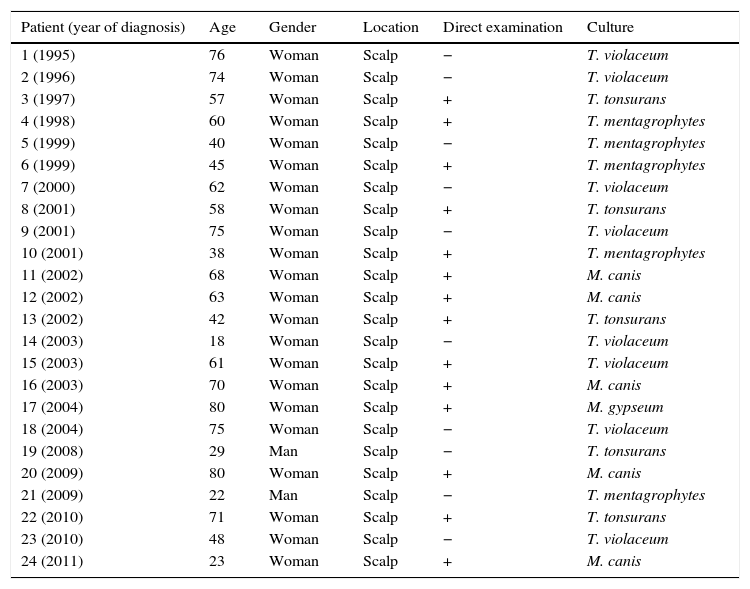

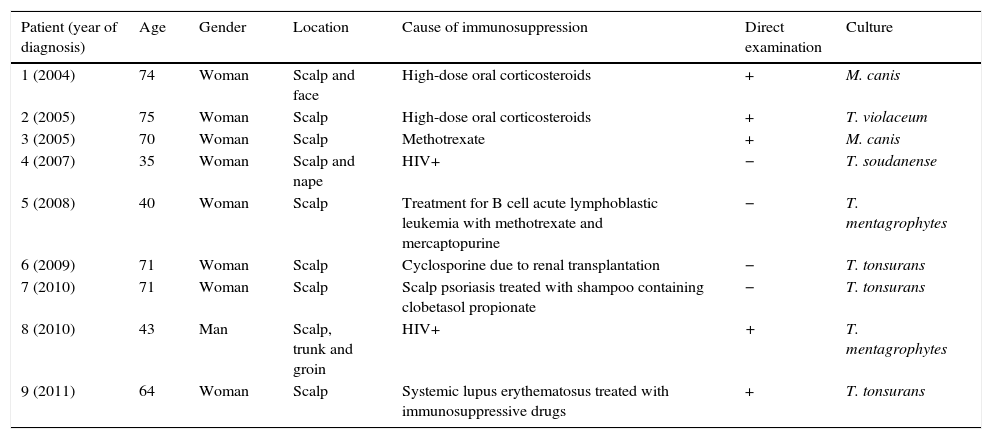

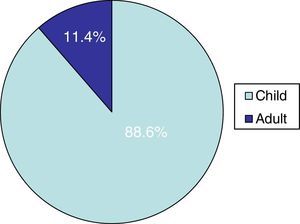

ResultsTinea capitis represented 22% of all the skin infections due to dermatophytes. Thirty-three cases (11.4%) out of the 289 cases of tinea capitis were from adults (Fig. 1). Most of these adults (72.7%) were immunocompetent (Table 1), while the others were immunocompromised for different reasons (Table 2). Only three of these adult patients were men, as compared to 30 women, most of them postmenopausal (21 patients, 70%).

Clinical and microbiological characteristics of the immunocompetent patients.

| Patient (year of diagnosis) | Age | Gender | Location | Direct examination | Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (1995) | 76 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 2 (1996) | 74 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 3 (1997) | 57 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. tonsurans |

| 4 (1998) | 60 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. mentagrophytes |

| 5 (1999) | 40 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. mentagrophytes |

| 6 (1999) | 45 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. mentagrophytes |

| 7 (2000) | 62 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 8 (2001) | 58 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. tonsurans |

| 9 (2001) | 75 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 10 (2001) | 38 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. mentagrophytes |

| 11 (2002) | 68 | Woman | Scalp | + | M. canis |

| 12 (2002) | 63 | Woman | Scalp | + | M. canis |

| 13 (2002) | 42 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. tonsurans |

| 14 (2003) | 18 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 15 (2003) | 61 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. violaceum |

| 16 (2003) | 70 | Woman | Scalp | + | M. canis |

| 17 (2004) | 80 | Woman | Scalp | + | M. gypseum |

| 18 (2004) | 75 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 19 (2008) | 29 | Man | Scalp | − | T. tonsurans |

| 20 (2009) | 80 | Woman | Scalp | + | M. canis |

| 21 (2009) | 22 | Man | Scalp | − | T. mentagrophytes |

| 22 (2010) | 71 | Woman | Scalp | + | T. tonsurans |

| 23 (2010) | 48 | Woman | Scalp | − | T. violaceum |

| 24 (2011) | 23 | Woman | Scalp | + | M. canis |

Clinical and microbiological characteristics of the immunocompromised patients.

| Patient (year of diagnosis) | Age | Gender | Location | Cause of immunosuppression | Direct examination | Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2004) | 74 | Woman | Scalp and face | High-dose oral corticosteroids | + | M. canis |

| 2 (2005) | 75 | Woman | Scalp | High-dose oral corticosteroids | + | T. violaceum |

| 3 (2005) | 70 | Woman | Scalp | Methotrexate | + | M. canis |

| 4 (2007) | 35 | Woman | Scalp and nape | HIV+ | − | T. soudanense |

| 5 (2008) | 40 | Woman | Scalp | Treatment for B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with methotrexate and mercaptopurine | − | T. mentagrophytes |

| 6 (2009) | 71 | Woman | Scalp | Cyclosporine due to renal transplantation | − | T. tonsurans |

| 7 (2010) | 71 | Woman | Scalp | Scalp psoriasis treated with shampoo containing clobetasol propionate | − | T. tonsurans |

| 8 (2010) | 43 | Man | Scalp, trunk and groin | HIV+ | + | T. mentagrophytes |

| 9 (2011) | 64 | Woman | Scalp | Systemic lupus erythematosus treated with immunosuppressive drugs | + | T. tonsurans |

In the group of postmenopausal women, 15 (71%) were immunocompetent, while 6 (29%) were under pharmacological immunosuppression (Table 2): one of them was having methotrexate, two others were under high-dose oral corticosteroids treatment, another one was having cyclosporine after kidney transplantation, one woman with scalp psoriasis regularly used a shampoo containing clobetasol propionate, and the last one suffered systemic lupus erythematosus and was receiving an immunosuppressive treatment (Fig. 2).

Only 2 out of the 9 non-postmenopausal women were immunocompromised: one woman was receiving treatment for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with methotrexate and mercaptopurine, and the other was HIV positive (Fig. 3). All three adult males were young, with one being HIV positive.

Amongst the adult patients, species of Trichophyton (T. violaceum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, T. tonsurans and Trichophyton soudanense) were isolated in 76% of the cases, and species of Microsporum (M. canis and M. gypseum) were present in the remaining 24%. All those patients in whom Trichophyton species were isolated were successfully treated with oral terbinafine, while those in whom Microsporum species were isolated were also successfully treated with oral griseofulvin. None of the patients had any treatment-related adverse effects.

DiscussionThe incidence of tinea capitis in our country is higher in children (88.6%) than in adults (11.4%). In adult patients, species of Trichophyton were isolated in 76% of the cases, and species of Microsporum (M. canis and M. gypseum) in the rest. This fact contrasts with the data found in children in our geographical region, as M. canis is by far the main causative agent of tinea capitis in childhood (63.5%).8

Although tinea capitis is considered rare in adults, as shown in this and other studies,13,22,25 it is nevertheless far from being exceptional. Many papers offer percentages that are similar to ours; a study carried out in the Afro-American population in USA showed an incidence of 11.4% of tinea capitis in adults.29 In France, a study by Cremer et al. reported a rate of up to 11% of tinea capitis in adults in a period of one year.7 However, in Greece, a study covering a period of 15 years found a case rate of only 5.8%.9 In China, the incidence of tinea capitis in adults ranged from 6% to 13.6% in two different studies.30,32 However, in Taiwan, according to a paper dated in 1991, the incidence in adults appears to be much higher, reaching 63%.19 Our percentage is closer to the figures published in Europe, being very similar to that for France but higher than that in Greece, which covered a similar period of years. Our result is also similar to the percentage found in the Afro-American population in the USA.

The causative agent of this clinical form can vary depending on the geographical area. For example, in USA, Canada, United Kingdom and Brazil the main pathogen is T. tonsurans,4,6,24 followed by M. canis and T. violaceum. In Italy, however, M. canis predominates, although T. mentagrophytes and T. violaceum are also isolated.3,15T. violaceum is the most common agent in Greece,12 Egypt,10 Tunisia21,28 and Taiwan,31 as well as in our study, where it was found to be the causative agent in 27% of the cases, closely followed by T. tonsurans (24%). In China, T. violaceum causes over 50% of the cases of scalp ringworm in adults.31 In poorer countries, scalp infections caused by T. soudanense or Microsporum audouinii are more prevalent.17 In our study, T. soudanense was only isolated in one case, a HIV-positive immigrant woman (Fig. 2). This dermatophyte is an anthropophilic fungus endemic in different African countries, though it is an emerging species in areas where zoophilic dermatophytes predominate as agents of tinea capitis, like Spain,26 USA,20 New Zealand18 or Italy,27 due to factors such as adoption and immigration.

Previous studies have already documented a higher incidence of adult tinea capitis among menopausal women,10 explained by the involution of sebaceous glands following decreased blood estrogen levels during menopause.

The choice of the oral antifungal drug depends on the characteristics of the patient; griseofulvin has been used widely and, more recently, also terbinafine. Ketoconazole, itraconazole and fluconazole are used in a lesser extent. In AIDS patients, for example, some authors have used terbinafine,14,23 though it has not always proven effectiveness in cases of tinea capitis due to M. canis.5 Frequent and important adverse reactions have been reported with griseofulvin, mainly in transplant patients due to its interaction with cyclosporine.11 Moreover, several studies have shown a higher efficacy of terbinafine compared to griseofulvin in half the time (4 weeks vs. 8 weeks) in tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton, with a better profile of tolerability.1,16 Although in tinea capitis caused by M. canis griseofulvin continues to be the treatment of choice, recent studies have also shown good results with terbinafine.2

Our study shows that tinea capitis is not an uncommon problem among the immunocompetent adult population. It primarily affects postmenopausal women and often presents an atypical clinical pattern, which can easily lead to confusion with other dermatoses, resembling bacterial folliculitis, folliculitis decalvans, dissecting cellulitis, or the scarring related to lupus erythematosus. Consequently, the correct diagnosis and treatment is delayed in many cases, increasing the risk of new infection. In our geographical area, most of the cases affecting the adult population are caused by species of the genus Trichophyton. In these cases, the treatment of choice was oral terbinafine, which considerably shortens the treatment and shows fewer side effects than the classical griseofulvin. This fact should be emphasized considering the relatively high number of immunocompromised patients among all the cases included in this study.

Financial supportNone.

Conflict of interestNone.