Head and neck canceris a major health problem globally with the projected incidence of 1,176,149 cases, an approximate 20% increase, in 2020. Most research today is directed towards reducing this incidence by understanding the mechanism and etiologic factors associated. Majority of these factors are habitual, with tobacco use being the most common. There are many variations in the use of tobacco ranging from smoked to smokeless, as well as novel innovations like e-cigarette and tobacco tablets, being introduced today. There are also many studies suggesting tobacco use as a gateway drug to other habitual substances, including alcohol and marijuana use. Many of these substances are now being utilized more by the youth than adults, which might develop a shift in the age of incidence in the future. Few countries have asignificant population of immigrants, who bring with thema diverse range of traditional habits, the effects of which still have to be studied on the population. An overview of the various habitual etiologiesassociated with head and neck cancers, and their mechanism of action have been reviewed here so as to get a holistic idea of these substances.

El cáncer de cabeza y cuello es un problema de salud relevante en el mundo, con una incidencia proyectada de 1176149 casos, un aumento aproximado del 20%, en 2020. La mayoría de las investigaciones actuales apuntan a reducir esta incidencia con la comprensión de los mecanismo de su génesis y los factores etiológicos asociados. La mayoría de estos factores son adicciones, siendo el uso del tabaco el más común. Hay muchas variaciones en el uso del tabaco que van desde con o sin combustión, así como novedosas innovaciones como el cigarrillo electrónico y las tabletas de tabaco, que se están introduciendo hoy en día. También hay muchos estudios que sugieren el uso del tabaco como una droga de entrada al uso de otras sustancias adictivas, incluido el consumo de alcohol y marihuana. Muchas de estas sustancias ahora están siendo utilizadas más por los jóvenes que por los adultos, lo que podría causar un desplazamiento en la edad de incidencia de estos cánceres en el futuro. Algunos países tienen una importante población de inmigrantes, que traen consigo una amplia gama de hábitos tradicionales, cuyos efectos en la población aún tienen que ser estudiados. Se revisaron aquí los mecanismos de acción de las diversas adicciones asociadas etiológicamente con los cánceres de cabeza y cuello, con el fin de dar una visión global del problema asociado al uso de estas sustancias.

The head and neck cancers contribute a significant amount towards the health burden world over, with a projected increase in incidence of 20% by 20201. Among these subsites, lip and oral cavity contribute the most, followed by larynx and oropharynx, while salivary glands are the least. Collectively, Hungary had the highest Age Standardized Rate (ASR) for collective head and neck cancers, while the most common, oral cancers, were found in the Asian subcontinent1. Quite a few countries today are contributing a significant amount of their GDP towards tackling these issues by understanding the etiology associated with these cancers. Among the various causative factors associated, tobacco plays a major role, alone as well as in an additive and multiplicative action with other substances. Most of these substances are becominghabituated by the youth, and in some places even more than adults2.In tobacco, the level of unprotonated nicotine affects the rate and degree of absorption into the bloodstream, which is relatively quick, causing an instant addiction, both physical and psychosocial3. To add to the numbers, there has been an increased effort by the industry to introduce alternative smoking methods, such as the e-cigarette, branding them to be less hazardous4. Another interesting factor is the effect of immigrants introducing their traditional habits world over, the effects of which now have to been seen in these varied population groups.

Most of these substances are addictive, with tobacco often being cited as a “gateway drug” influencing the use of other habituating substances5. As per a Surgeon General's Report, adolescent teens (12-17 year olds) who smoked, were three times more likely to use alcohol, eight times more likely to smoke marijuana, and twenty times more likely to use cocaine than their non smoking peers6. With all these habituating and addictive carcinogenic substances being used at a wide spectrum of age and level of society we need to understand the mechanism of these agents, and hence we present this overview on the commonly used addictive carcinogenic substances globally.

TOBACCO AND ITS VARIOUS FORMSTobacco has been formally evaluated as a major etiologic factor for causation of cancers a while ago, accounting for nearly a third of the world's cancer mortality1.The initial association was only made for oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx and larynx, but in 2002 it was extended to include nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasopharynx7.The overall risk is related to the total lifetime exposure to the substance, including the quantity, frequency, age of initiation, number of pack years and also the exposure to second hand smoke8.

SMOKED TOBACCOThe concept that smoking causing cancer was initially suggested by Abbe et al in 1915, who observed that smoking and alcohol consumption were common habits amongst oral cancer patients9. About 25 million boys and 13 million girls are estimated to be smoking tobacco globally, with the highest in the WHO EURO region (75.3%)2. Countries having a higher number of adolescent smokers than adults included Ethiopia, Nigeria, Qatar and Senegal2.

CigarettesThe total nicotine available in a commercially available cigarette is about 16.3mg/g10. In this form of smoking blond tobacco is most commonly used. There are also flavored cigarettes available today, most commonly mentholated. The metabolism of nicotine to cotinine is inhibited by menthol and hence increases its half-life11. In the oropharynx the sites most commonly affected are the crypts of the tonsils, glossotonsillar sulcus and the tongue base, probably due to the prolonged exposure of the pooled saliva in these areas. Lubin et al concluded that more cigarettes smoked/day for a shorter duration was less deleterious than lesser cigarettes/day for a longer duration12. The pooled OR for cigarette smoking has been found to be 2.33(1.84-2.95), 4.97(3.67-6.71) and 6.77(4.81-9.53) for light smokers (≤19/day), moderate smokers (20–39/day) and heavy smokers (≥40/day), respectively13.

Cigar and pipesA cigar is a rolled bundle of dried tobacco that is available in a variety of shapes and sizes, most commonly the Parejo or Coronas. They are manufactured predominantly in Central and South America where most of the cigar tobacco is grown. They are also produced in the USA, Mediterranean countries and South East Asian countries like Indonesia and Philippines. Most cigar smokers do not inhale the smoke, as it is more irritating than cigarette smoke, and hence may have a stronger association with oral cancer than other sites. Pipe smoking is similar in the sense that it was traditionally meant for tasting the tobacco as opposed to inhaling, and hence has a similar predilection for oral cavity cancers. Parkin et al found that pipe smoking had a similar risk of developing oral and oropharyngeal cancer as compared to cigarettes (OR=3.8 vs 3.9, CI=1.1-12.6 vs 1.6-9.4) while cigar smoking was almost three fold higher (OR=8.3, CI=2.1-31.9)14.

Waterpipe smokingA paper on the epidemiology of waterpipe smoking shows that this traditional Middle Eastern method of smoking has become a global phenomenon amongst the youth, majorly due to the introduction of flavored tobacco15. There is a higher percentage of the population in the Arab world smoking waterpipe than cigarettes16. Contrary to the perception of the relative safety of waterpipe smoking, a meta analysis found it was associated with increased risk of head and neck cancer (SRR 2.97; 95% CI 2.26–3.90), esophageal cancer (1.84; 1.42–2.38) and lung cancer (2.22; 1.24–3.97)17.

SMOKELESS ORALMuch of these affect the oral and oropharyngealsubsites, with a higher incidence in the developing South East Asian and African subcontinent, arising at the site of placement of the quid1. Potentially malignant lesions also have a higher correlation with smokeless than smoked tobacco. As the pH of these products increase, the more the protonated nicotine is available, further contributing to a higher potential toxicity. On comparing the pH among the various verities of smokeless tobacco, the highest values were seen in naswarfrom Uzbekistan and toombak from Sudan18. Over time these values have seen a decline leading to less addiction, but the problem still exists in large enough numbers. Commonly used alkylating agents such as ammonium carbonate and sodium carbonate, are often added to these products to increase the pH and enhance the absorption.

Loose leaf chew/ShammahLoose leaf chew is the simplest form of chewed tobacco sold majorly in the USA, while moist plug is a similar preparation pressed into bricks. In the Arab nations, shammah is a similar preparation available. It is usually held at the back of the mouth to cause oral, oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal carcinoma as well19.

Nass and NaswarThese are mostly available in Central Asian countries like Iran, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Nass is tobacco and ash mixed with sesame or cotton oil along with water and sometimes gum. Naswar is the same mix with slaked lime and flavoring agents like cardamom oil and menthol20.

Paan and GutkhaOral tobacco is mixed with betel leaf, slated lime and areca nut to form a quid called ‘paan’. This is majorly used in Southeast Asia and when a flavoring agent is added it is commonly consumed as a mouth freshener. The lime used lowers the pH so as to accelerate the release of alkaloids. Chewing paan most often correlates with alveolo-buccal cancer as well as premalignant lesions18.

Gutkha is a pre mixed dried form of areca nut, slaked lime, spices, flavoring agents and tobacco. Due to the increased consumption in youth population and the risk of oral cancer, few Indian states have banned the manufacture and distribution of Gutka and Paan masala21.

Oral snuffA mix of tobacco and lime in India is known as Khaini while Toombak is a similar form used in Sudan. Sweden has the highest per capita consumption and sale figures of snuff in the world, and the habit is becoming increasingly popular22. The Sudanese form uses the sp. Nicotianarustica mixed with soda bicarbonate. It is either available loose or portion-bag-packed, most often rolled into a ball weighing about 10gm, called a saffa. It is used as a pinch or dip in the west most often placed in the vestibule of the upper lip, while in Southeast and African countries it is in the inferior gingivobuccal sulcus18. They are used most often in the rural areas among men aged 30 years and older, forming a distinct lesion at the site of use22. In the USA low-TSNA moist snuff is also available and marketed as a “safer” product, as well as hard snuff or lozenges. The highest amounts of NNK and NNN were seen in some moist snuff brands in the USA (135 and 17.8mg/g tobacco, respectively)18. However, homemade toombak has values as high as 3085 and 7870mg/g, respectively18. In Tunisia, a similar snuff preparation called “neffa” is traditionally used.

Gudaku/Mishri and Mawa/ZardaSometimes also called Gul, Gudaku or Mishri is used in Central and Eastern India and Bangladesh as a teeth-cleansing abrasive by the locals in the villages. Bajjar is another similar substance used on gums, often leading to alveolus cancers. Another similar product marketed as Ipco in India, and used in some parts of the UK, is a tobacco toothpaste or creamy snuff, which is primarily used by women.

Mawa is a rubbed mixture of sun cured areca nut with tobacco and slaked lime. It is most often used in Western India and Bangladesh. When mixed with spices and dried it is called Zarda.

Chimó or KimamIn Venezuela, chimó is the most common form of smokeless tobacco. The tobacco leaf is crushed and boiled for several hours along with sodium bicarbonate, brown sugar, ashes from the Mamón tree, to make a paste that is seasoned with vanilla and anisette flavoring. The incidence has increased exponentially with one study showing 13.5% of boys in grades 6-9 (13-16 year old) using it23. In the Asian subcontinent and Africa a similar paste is made with the addition of saffron or cardamom, called Kimam/Khiwam or Qiwam. A small mount is placed between the lips and cheek especially the lower gingivobuccal region.

Iq’mikIq’mik is a form of fire-cured tobacco mixed with punk ash, used by almost 52% of Alaskan natives including teething babies24. The punk ash is believed to raise the pH in the mouth, facilitating maximum delivery of nicotine. Users break of a small piece and chew it until soft.

SMOKELESS NASALDry snuffIt is most often associated with sinonasal carcinoma or nasopharyngeal cancers. A pinch of fire cured tobacco leaves crushed into a powder, is sniffed through the nostrils. Its use is the highest in Sweden and other countries like the USA and UK. About 8% of people in Bhutan chew or sniff tobacco (7% women and 10% men), in a country where tobacco sale is prohibited25. Sankaranarayananet al investigated the association between nasal snuff use and cancers of the oral cavity subsites in men. They found a 3.0 times higher relative risk of developing cancers of the tongue, floor of mouth, gingiva and buccal and labial mucosa compared to non-users. The same group found a 1.2 times higher relative risk in development of laryngeal cancers in snuff inhalers26–28.

ALCOHOLAlcohol is the second most common etiologic agent causing cancer and has been classified as a class I carcinogen, particularly in oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx and hypopharynx. The multiplicative effect of alcohol and tobacco is well established, particularly in high levels of exposure. Zhang et al in their meta-analysis concluded that the odds ratio and confidence interval for developing head and neck cancer was highest in heavy drinkers, i.e. 6.63 (5.02-8.74). They also found that tobacco had a stronger association with these cancers than alcohol did, but was still an independent causative factor13. Another study suggested that greater drinks/day for a shorter duration was more deleterious than fewer drinks/day for a longer duration. They also found a greater pharyngeal and oral cavity cancer risk with alcohol consumption, which was derived from the effects of drink-years and not drinks/day12.

MATÉ OR CHIMARRÃOMate is a beverage resembling tea made from fermented leaves and stems majorly consumed in South America. Its use has been linked to tongue cancers, with the highest risk association with oropharyngeal cancers29. A Brazilian group found the risk of developing esophageal cancers increased in a dose dependent manner. Even the temperature of intake has been studied, concluding that very hot consumption had a 3-fold increase risk than hot mate30. Most of the carcinogenic effects are due to the phenolic compounds, as well as the tannins and N-nitroso compounds30.

MARIJUANAMarijuana is the most commonly used form of illegal recreational drug smoked after tobacco. Like tobacco smoking, its use has been associated with similar respiratory pathologies and cancers acting by inducing cytogenic changes like breaks, deletions and translocations31,32. There are a few relatively small studies linking head and neck cancers with the long-term habitual use of marijuana, and all suggest a young age of incidence and more aggressive disease33.

DISCUSSIONAlthough cigarette smoking is the most common form of tobacco use globally, other forms also have an equally deleterious effect. Majority of the evidence available has been on cigarette smoking, while the contemporary literature has shed light on alternative methods of tobacco use. Despite this overwhelming evidence against tobacco, almost 1.1 billion people worldwide still smoke today2. The incidence has declined in the developed world but it is on the rise in the low or middle-income countries, accounting for 80% of the global smokers1. This may be attributed to the fact that these countries have a compromised government policy on raising awareness about the nuisance of tobacco use. The distribution of these habitual substances is not uniform throughout the world. Due to the effects of immigrants moving across continents, we see a lot of the traditional practices of one region being adopted in other regions, especially from the Asian subcontinent. In the UK, majority of the betel quid chewing population include immigrants from the subcontinent34. Many of the Arab countries where immigration is very high, the large expatriate community contribute heavily to the overall betel nut chewers35. These countries should invest in research towards these immigrant-endemic habits and have tailored programs designed especially addressing these issues. Another aspect is to incorporate these indigenous habits, especially those less popularized like waterpipe smoking, in the list of substances causing health hazards.

The prevalence of other novel products has also increased, especially the use of e-cigarettes and nicotine gums. Although claimed as being “less” dangerous than smoking tobacco, the long-term effects of these products still needs to be studied. The consumption of most of these contemporary products is by the youth. Among the youth e-cigarettes are now the most commonly used tobacco product, surpassing cigarette smoking in 2014, with a third of the adolescents having at least once tried e-cigarette36. This further underscores the need to implement more effective tobacco control programs targeted towards the younger generations and help provide cessation for those already using. The increase in tobacco taxation is also a major intervention that can be implemented by countries, as the youth are more sensitive to the increase in tobacco price.

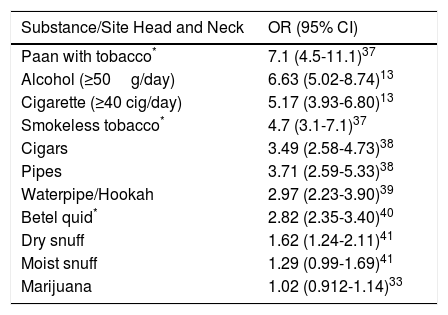

| Substance/Site Head and Neck | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Paan with tobacco* | 7.1 (4.5-11.1)37 |

| Alcohol (≥50g/day) | 6.63 (5.02-8.74)13 |

| Cigarette (≥40 cig/day) | 5.17 (3.93-6.80)13 |

| Smokeless tobacco* | 4.7 (3.1-7.1)37 |

| Cigars | 3.49 (2.58-4.73)38 |

| Pipes | 3.71 (2.59-5.33)38 |

| Waterpipe/Hookah | 2.97 (2.23-3.90)39 |

| Betel quid* | 2.82 (2.35-3.40)40 |

| Dry snuff | 1.62 (1.24-2.11)41 |

| Moist snuff | 1.29 (0.99-1.69)41 |

| Marijuana | 1.02 (0.912-1.14)33 |

We do not have any financial and personal relationships with other people or organization that could inappropriately influence our work. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Role of funding sourceThere is no role of funding source in this article. We confirm that we had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.