Chile is uniquely situated to be a leader in South American development of the specialty of Emergency Medicine. Chilean emergency medicine has successfully transitioned from a novelty training idea to a nationally and internationally recognized entity with serious public health goals. There are more residency training programs in Chile than in any other South American or Latin American country, and the specialty is formally recognized by the Ministry of Health. Chilean emergency medicine thought leaders have networked internationally with multiple groups, intelligently used outside resources, and created durable academic relationships. While focusing on locally important issues and patient care they have successfully advanced their agenda. Despite this, the specialty faces many new challenges and remains fragile but sustainable. Policy makers and the Chilean MOH need to be acutely aware of this fragility to preserve the progress achieved so far, and support ongoing maturation of the specialty of Emergency Medicine.

The Republic of Chile is a country of over 17 million people with 85% of the population living in urban settings. Almost half of the population lives in the greater Santiago metropolitan region and the area around Viña del Mar directly west of Santiago. The country is a democratic republic, economically stable, and resource rich (copper, agriculture, viticulture and wine production, fisheries, and tourism)1. The population of Chile is aging rapidly and growing at a relatively slow pace with geriatric considerations prominent in long term medical and economic planning for the country. Fifteen percent of the country is age 60 or greater2. Catholicism is the main religion with relatively small groups of other Christians, Mormons, Jews, and Muslims. While private hospitals exist that accept private insurance, most Chileans use the public hospital system for emergent care.

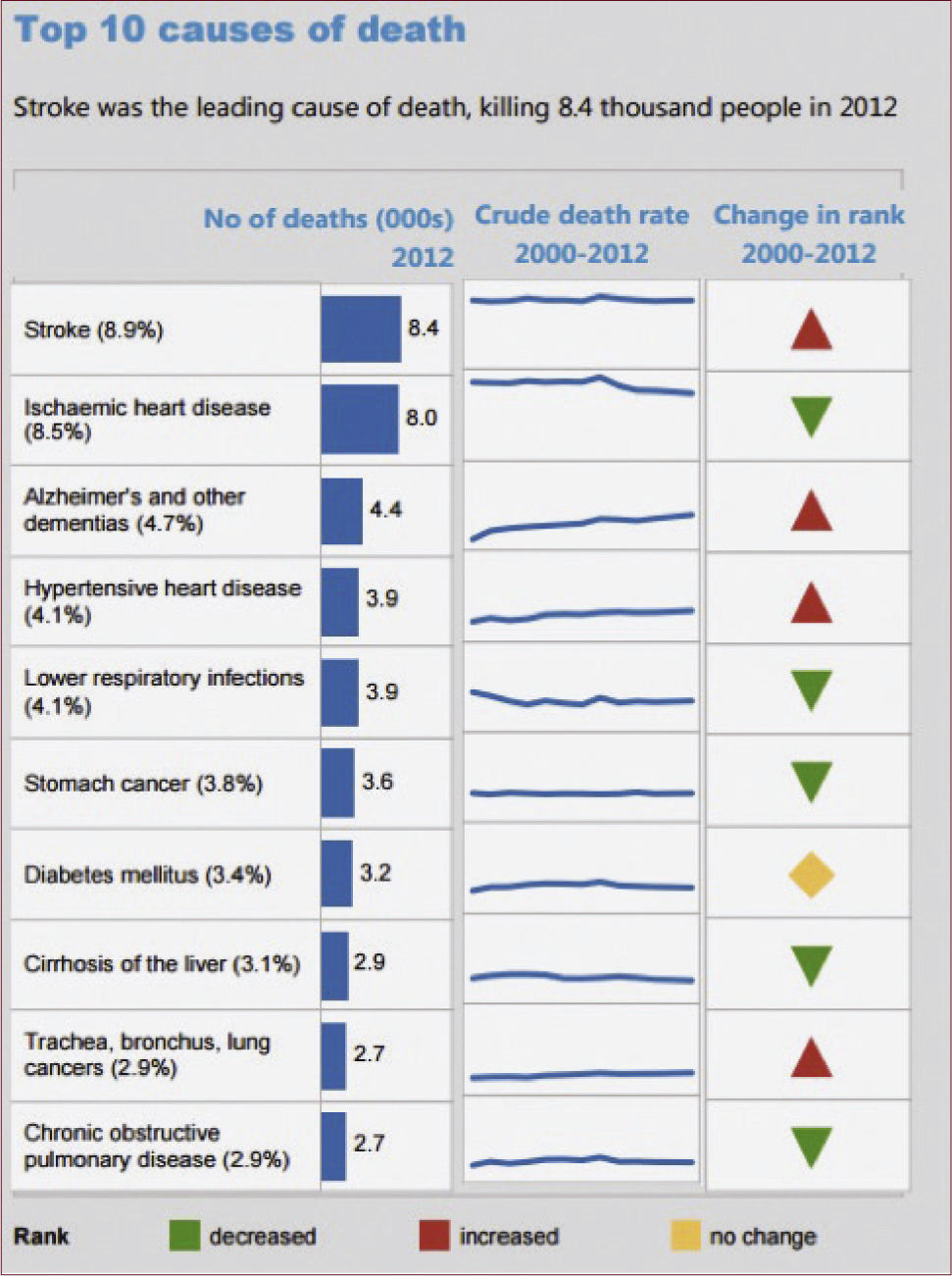

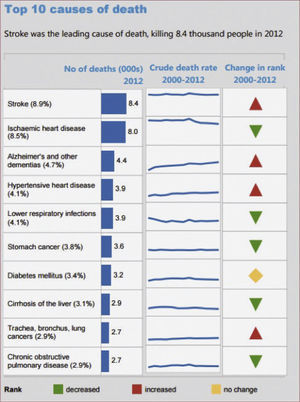

Chile hosts a national public health care program called FONASA (National Health Fund) which has four levels of fund, according to the affiliate's economic level and which serves over 80% of the population. Private insurance, which is more comprehensive, is available for those who can afford it. It is called ISAPRES and covers about 15% of Chileans. Workers’ compensation insurance is also nearly universal, and all employers make contributions to public healthcare funding. A military health care system with hospitals also exists. Thus, there is near universal coverage of the Chilean population, but it is not a single payor system. The nation spends less than 10% of its GDP on health and yet it has maintained excellent WHO health statistics (ranks number 33 in the year 2000) all of which is a tribute to the general overall performance and efficiency of its health care system3. Causes of death in Chile are summarized in the WHO data below (Figure 1).

Chilean medical education nationally is strong as well, with several long standing competitive medical schools that provide excellent foundational medical knowledge to their graduates, who take a national medical examination upon graduation. Residency training after medical school (usually 3 years in duration and often governmentally funded) is available in internal medicine, general surgery, and many other specialty areas. The larger Chilean universities are capable academic institutions with research and publication activities and academic promotion criteria, similar to those in academic institutions in the United States and Europe. In Santiago the two largest, oldest, medical institutions are the University of Chile and PUC (the Catholic University), and these were also among the first institutions to begin training Emergency Physicians. The University of Chile hosted the first Chilean Emergency Medicine (EM) training program which started with four physicians in 1994, and PUC began its program several years later.

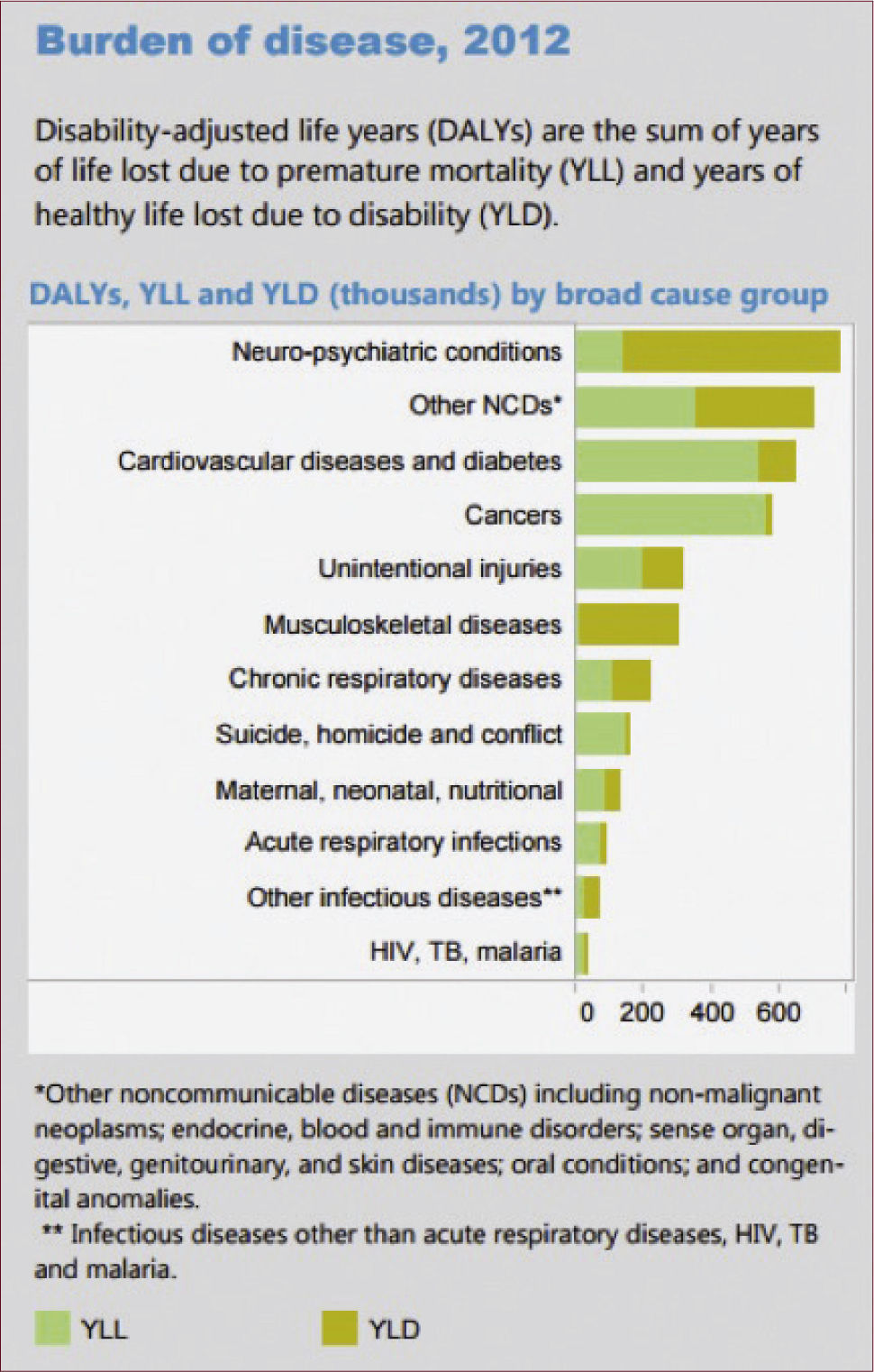

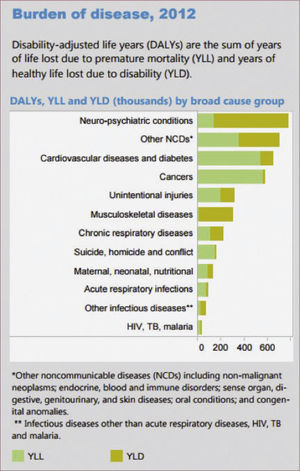

In 2005, there were 18 million ED visits in Chile and thus tremendous potential for EM specialty training to positively impact the health of the Chilean population. The specialty of EM was recognized by the Ministry of Health (MOH) in 2013. Healthcare in Chile is considered to be a right, and there is a patients’ bill of rights adopted nationally in 20124. As of 1990, the need for trained Emergency Medicine specialists to minimize disability adjusted life years (DALYs) for non-communicable diseases and trauma in Chile was evident. (Figure 2)

Chile is the most progressive country in South America in terms of reaching the United Nation's Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (See Fig. 3). The Chilean national report yielded very positive results. Chileans met all the 2015 goals well ahead of schedule except for gender equality (#3) and combatting HIV/AIDS/malaria (#6) which are not prevalent in Chile. One criticism of the MDGs is that they don’t provide any comprehensive cross sectional health care data or any system performance data beyond the specific health measures identified within the MDGs. Emergency medicine development is not specifically articulated as a MDG5.

MODERN EMERGENCY MEDICINE IN CHILEAs of 1990, there was no EM specialty training in Chile, and most emergency rooms were simply divided into a “medical” side, a “surgical” side and a “pediatric” area. As noted above there were some 18 million ED visits in 2005 and at that time there were less than 50 trained emergency physicians. There were very few career oriented emergency physicians and most emergency care providers were younger doctors often in transition to another specialty training area or working in a locum tenens fashion. There was, at that time already a public EMS/Prehospital Care system in place (SAMU) with a universal access phone number (131), but there was inadequate ambulance coverage of even the urban areas of the country. Prehospital capacity augmentation via secondary private ambulance services emerged in the urban centers in Chile including H.E.L.P., Unidad Coronaria Movile, and others via paid subscription and on-scene payment. Thus the prehospital arena was then, and remains now, relatively fragmented. At that time, some career interested emergency physicians worked for SAMU, and some worked sporadically in both emergency rooms and critical care settings. In Chile, firefighters are not cross-trained as paramedics as they are in the U.S. and fire-related emergencies are managed completely separately from medical emergencies.

Currently, Chile lacks a formal regionalization of trauma care and there is no national or metropolitan trauma registry gathering medical injury data. The regionalization of trauma care and concentration of trauma care resources in designated trauma receiving medical centers is an obvious need. The larger public hospitals are the most obvious targets for this evolution, and generally one trauma center is needed per 1-1.5 million population6. Trauma care in Latin America will likely improve most by first improving prehospital and emergency department care7,8.

The argument in favor of developing EM that was presented to the Chilean government and Ministry of Health in the 1990's included the large number of national EM visits, long waiting times in many public hospitals emergency rooms, and the potential public health benefits related to rapid identification and treatment of non-communicable disease entities9. Eventually this rationale was accepted and the government embraced the concept of emergency medicine as a specialty and began to fund training positions in the country. Funding often had tied to it a public hospital service commitment post-residency of 3-5 years. The length of this commitment is a delicate issue for the specialty and its survival10. On the “pro-” side this commitment helps to retain new EM residency training graduates in the public hospital care arena and addresses the maldistribution of physician resources. On the “con-” side if the “payback” is too long or onerous, graduating medical students will have a disincentive to consider EM as a specialty career choice. Ultimately, EM development should remain as a public health priority in Chile with local advocates, national, and transnational/international groups in active dialogue with Chilean health policy experts, health economists, and the Ministry of Health to support Chile's new emergency medicine community11.

As noted above, formal EM training began in 1994 at the University of Chile. A few years later PUC, and the University of Santiago and Clinica Santa Maria (University of San Sebastian), added additional training sites. The Santiago-based training programs are relatively strong academically and host several experienced career EPs as faculty, most at the assistant professor academic rank. These urban Santiago programs are designed to have 4-12 residents per year with a three-year training duration. Each of the training programs in Chile has a primary academic institution and most also have an affiliated public institution that they are partnered with. The curriculum and core content of these programs loosely follows the American core content with some modification to meet Chilean needs, pathology, and epidemiology. Curriculum transfer and export helped to rapidly advance these training programs in the 1990s assisting the development process.

Academic development of EM is proceeding in Chile but most of the training programs are hosted within the Departments of Internal Medicine or Surgery. Independent academic units for emergency medicine with academic autonomy are still several years off in most institutions. Most of the emergency medicine divisions are lean in terms of faculty numbers, and academic salaries are still relatively low. Very few faculty have progressed beyond the assistant professor rank. Faculty development is critical to the long term viability of EM in Chile but it requires both resources and time12. Furthermore, the clinical hours for many EM faculty are excessive and not compatible with academic development. There is inadequate protected time, inadequate faculty mentoring, and few independent peer-reviewed publications to allow for academic promotion. As a new specialty this is not surprising, but academic productivity must be addressed as a priority in the future. International EM programs in the United States and Europe can assist these academic units with curriculum transfer, focused training programs, research and publication, and prepackaged educational materials saving each new academic unit from “reinventing the wheel”13.

New graduates of the existing training programs are successfully being integrated into the Chilean health care system and many are actively recruited to high quality private hospitals and academic positions. Having noted that, very few hospitals have an emergency department fully staffed with EM trained physicians. Mixed groups of physicians staff the national emergency departments, but presumably as the current training programs add to the pool, more physicians trained in EM will staff emergency departments in the future. Distribution of these graduates beyond the Santiago metropolitan region is desirable, but there are still great needs in Santiago.

International exchanges and longitudinal academic support have played a prominent role in the development of EM in Chile, and many different institutions have been involved over the years. A partial list (those known to the authors) includes:

- 1.

University of Southern California: 20+ years with student, resident, and faculty exchanges, educational support, consulting and sabbatical exchanges and faculty mentoring

- 2.

UCLA: Hosting international fellowship training for Chileans, and faculty mentoring

- 3.

Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minnesota: Conference support and sponsorship, faculty development, current host of the ACEP ambassador to Chile

- 4.

Stony Brook University: Conference support, resident exchanges

- 5.

George Washington University: Educational support and consulting

- 6.

University of North Carolina: Educational support and consulting

- 7.

Harvard University: Educational support and consulting

- 8.

ACEP representatives: Educational support and consulting

- 9.

EM: Reviews and Perspectives, Emergency Medical Abstracts, Essentials of EM and other conferences and business interests have provided tuition discounts and international pricing options, faculty mentoring

- 10.

Fulbright Program (Valenzuela, R: Regionalization of Trauma Care Project, 2015)

This list is an excellent manifestation of the 8th MDG which focuses in on global partnerships as a vehicle for development. Emergency medicine in Chile is a prime example. Longitudinal support programs have been shown to have greater impact than shorter consultation efforts in Chile.

ORGANIZED MEDICINE AND SOCIETIES FOR EMERGENCY MEDICINE IN CHILEPrior to EM having its own representative body, the critical care society (SOCHIMI) allowed EM professionals a place to meet, lecture, and present their research from the mid-1990s onward. This permissive and inclusive behavior within the critical care community was critical to EM development in Chile, and reflects the close parallel interests of EM and critical care. Eventually this partnership led to EM residency graduates in Chile having access to a single additional year of training with access to critical care board certification. The evolution of EM in Chile allowed a retention of close ties to critical care which was very different to the U.S. evolution where early on the split away from critical care initially helped define the specialty, but hindered academic and research development later on.

There are now three societies that link emergency medicine interests in Chile. Each society covers a specific aspect of emergency medicine.

1. SOCHIMI: Sociedad Chilena de Medicina Intensiva which represents the critical care aspects of emergency care. Some of the early champions of emergency medicine in the 1990s had ties or indeed their origins in critical care. Most notably, José Miguel Mardonez, MD (considered a father of modern EM in Chile) started his career in critical care.

2. SOCHIPRED: Sociedad Chilena de Medicina Prehospitalaria y Desastres which represents the prehospital care aspects of EM including mass casualty and disaster response. Ambulance personnel, paramedics, physicians, and SAMU system directors are represented in this group.

3. SOCHIMU: Sociedad de Chilena Medicina Urgencias is the newest of the three and represents the core of EM clinical practitioners. This group eventually presented Chilean EM interests to the International Federation of Emergency Medicine (IFEM) and Chile is now an Associate Full Member of IFEM. The development of EM in Chile with entrance to IFEM occurred at a relatively rapid pace and places Chile in the position o f a leader in South America.

Challenges remain for these 3 groups, and they are yet to have a large combined meeting, and the groups are not cohesive or particularly politically active. Membership is fragile in SOCHIMU and if new graduates and trainees do not join, this critical organizational unit could be lost. The leadership of SOCHIMU must be able to represent the entire group and avoid local partisan behavior or favoritism toward any particular interest to succeed and continue to grow. SOCHIMU must also work within the Chilean house of medicine (and the academics) to create a board examination, determine how to close the “practice track”, and how to represent not just the interests of the physician members but also the patients they serve effectively.

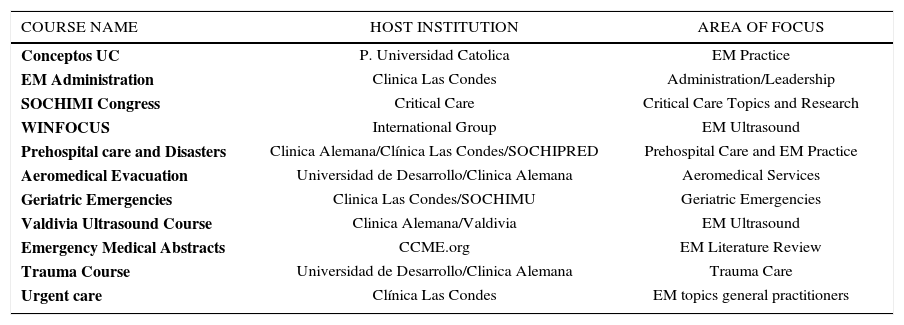

EDUCATIONAL MEETINGS WITH AN EM FOCUSThe American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) country report for Chile (last updated in 2015) lists numerous educational activities happening within Chile that pertain directly to EM training and expertise14. These help foster cohesion, serve to enhance the interest in EM and allow opportunity for more international collaboration. Below (Table 1) is a partial list of the higher profile educational offerings in which have happened in Chile and several are annual events like “Conceptos”. The educational activities reflect a vibrant community with academic, administrative, and procedural considerations. Specific epidemiologic concerns of national interest like geriatric emergencies and trauma care are represented in content clearly developed specifically for Chile.

ACADEMICS ACTIVITIES IN EM IN CHILE

| COURSE NAME | HOST INSTITUTION | AREA OF FOCUS |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptos UC | P. Universidad Catolica | EM Practice |

| EM Administration | Clinica Las Condes | Administration/Leadership |

| SOCHIMI Congress | Critical Care | Critical Care Topics and Research |

| WINFOCUS | International Group | EM Ultrasound |

| Prehospital care and Disasters | Clinica Alemana/Clínica Las Condes/SOCHIPRED | Prehospital Care and EM Practice |

| Aeromedical Evacuation | Universidad de Desarrollo/Clinica Alemana | Aeromedical Services |

| Geriatric Emergencies | Clinica Las Condes/SOCHIMU | Geriatric Emergencies |

| Valdivia Ultrasound Course | Clinica Alemana/Valdivia | EM Ultrasound |

| Emergency Medical Abstracts | CCME.org | EM Literature Review |

| Trauma Course | Universidad de Desarrollo/Clinica Alemana | Trauma Care |

| Urgent care | Clínica Las Condes | EM topics general practitioners |

www.sochimu.cl

While Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) have all been offered in Chile, the current training programs in Emergency Medicine do not emphasize these short courses.

There is a Chilean Chapter of the American College of Surgeons and in 2016 this chapter celebrated “30 years of ATLS” in Chile. ATLS training by the Chilean chapter has included both student and instructor courses in Chile and in the surrounding countries. In Chile 7582 physicians have done this course.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE CHALLENGESEmergency medicine has had a successful and rapid development in Chile. The new specialty is ideally suited to improve initial hospital care, diagnostics, and transitions to inpatient Chilean medical, surgical, and critical care services. Chile is now a leading nation and example for South America and no other country in the region has 10 training programs. The currently existing EM residencies in Chile (of variable academic quality) host approximately 150 resident trainees in EM and are now self-sustaining and supported by the MOH. The first goal of these programs is to get clinically competent trained EPs into many of the larger hospitals across the country starting with the urban centers (both public and private). The new graduates are the pioneers of the specialty and must work to meet the emergency care needs of the country. A list of some of the specific challenges ahead for EM in Chile. Lessons learned from EM development in other countries development struggles are emphasized in an article from Arnold JL, et al15. A summary is as follows:

1. Quickly expand to meet the clinical needs of the of the acutely ill Chilean patient population, and remain focused on this goal. Adding value from the public health and the patient's perspective will be critical to long term emergency medicine success16.

2. Strengthen the existing EM residency training programs so that the training offered is as comprehensive as possible, and has less variability from program to program. Strengthening the existing programs and expanding them should be a higher priority than creating additional new programs because currently there are not enough trained faculty to lead additional high quality training programs.

3. Begin making steps toward the regionalization of trauma care, the creation of a trauma registry, and the designation and certification of trauma centers.

4. A “board” of Emergency Medicine is necessary to strengthen the emergency medicine in CONACEM (Comision nacional de certificacion de especialidades medicas) to ensure the quality and uniformity of training.

5. A unified emergency medicine evaluation needs to be developed, for Chilean EM graduates.

6. Enhanced faculty development programs must be promoted, both locally and in conjunction with international partners.

7. Establish the value of SOCHIMU membership and continue to grow membership so that a cohesive society can represent the groups interests. SOCHIMU, SOCHIMI, and SOCHIPRED should coordinate a single academic meeting and recognize their mutual interests.

8. Recruit additional faculty to the existing training programs from the new graduate pool and possibly from international groups to augment the educational community.

9. Encourage ongoing international exchanges and fellowship training. These experiences give the Chilean emergency physicians perspective and membership in a larger community globally.

10. Create a Spanish language journal that will allow publication of regionally relevant material and help develop academic interests and faculty development.

11. Begin to make a greater contribution to “public health” and governmental health programs as articulated by the Minister of Health. A national Chilean position (below the MOH) pertaining to EM and Disaster Response makes good sense given the geological tectonics and volcanism of Chile and its history of recurrent major disasters. Development of regionalized trauma system for Chile is an obvious example of a reachable impactful public health goal.

12. Development of subspecialty training in areas of importance to Chilean healthcare needs to be created. Toxicology, Emergency Ultrasound, Prehospital Care, and Pediatric EM, are all areas worthy of development, and some have already begun.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, in relation to this article.