Organizations face a progressively ageing workforce and jobs with direct customer contact are growing, creating challenging issues from a human resource management perspective. Drawing on socioemotional selectivity theory and lifespan development findings, this study focuses on the research gap in the service sector with regard to age, emotional labour, and associated positive and negative outcomes. Analyses using data from 444 service employees in Germany revealed age is negatively directly related to exhaustion and cynicism, and positively directly related to professional efficacy, as well as positively directly linked to engagement. Additionally, age predicts less burnout and more engagement indirectly through the use of the emotion regulation strategies surface acting and anticipative deep acting. This provides evidence against the general deficit hypothesis of age, which assumes a decline of employee skills and abilities with age. We find no evidence that older workers are worse than younger workers, with older workers using positive emotion regulation strategies, being more engaged and less burnt out.

Las organizaciones se enfrentan a una mano de obra cada vez más envejecida y los puestos de trabajo de contacto con el público, en aumento, están planteando problemas desde la perspectiva de gestión de los recursos humanos. Basándonos en de la teoría de la selectividad socioemocional y en los descubrimientos sobre la evolución de la duración de la vida, este estudio centra su atención en el vacío de investigación que hay en el sector público con respecto a la edad, el trabajo emocional y resultados asociados positivos y negativos. Los análisis con 444 empleados en el sector servicios de Alemania han puesto de manifiesto que la edad se relaciona de un modo directo negativamente con el agotamiento emocional y con el cinismo, así como positivamente con la eficacia profesional y también con la implicación laboral. Además, la edad predice menos burnout y más compromiso laboral indirectamente, a través de la actuación superficial y de la actuación anticipatoria profunda mediante la utilización de estrategias de regulación emocional. Este hecho es una prueba contra la hipótesis de déficit general de la edad, que supone que las destrezas y aptitudes de los trabajadores disminuyen con la edad. No hemos comprobado que los trabajadores mayores sean peores que los jóvenes; es más, utilizan estrategias positivas de regulación emocional, tienen una mayor implicación laboral y un menor burnout.

The population of industrialised countries is changing with an increasingly ageing workforce. Along with changes in pension and retirement eligibility, this influences the age composition of the workforce, which means good knowledge of how age differences affect work variables is needed (Rauschenbach, Krumm, Thielgen, & Hertel, 2013) to underpin human resource practices. Indeed, employment rates of older workers (aged 55-64) have already increased in Europe from 40.6 percent to 53.3 percent between 2004 and 2015 (Eurostat, 2016). However, although the employment rate of older workers has increased, many employers seem reluctant to hire older workers as reflected by the lower reemployment rate of these workers compared to the total workforce. Despite anti-age discrimination policies, there continues to be age-related stereotypes about abilities and performance declining after 50 years of age. Even HR Managers responsible for designing and implementing age-related policies often hold stereotypical views of older (and younger) workers (Parry & Tyson, 2009). Specifically, this perception may be due to the widespread deficit hypothesis, which assumes a general decline of skills, abilities, and performance of older workers. This general deficit hypothesis may not be accurate, as although physical skills and abilities (Maertens, Putter, Chen, Diehl, & Huang, 2012) and cognitive abilities (Lindenberger & Ghisletta, 2009) may deteriorate with age, older workers demonstrate advantages through knowledge and experience (Baltes, Freund, & Li, 2005) and attitudes, motivation, and performance (Ng & Feldman, 2008, 2010).

Social and emotional competencies are relevant to most jobs; however, they have found only limited attention in the discussion of older employee skills and abilities (e.g., Johnson, Holdsworth, Hoel, & Zapf, 2013). Social skills and abilities are especially relevant for the service sector where interactions with clients are frequent, and emotion regulation is a core social competence in such job roles. The importance of employees having good social competence skills is evident when considering the growth of the service sector and the worldwide increase in jobs that involve direct customer contact (Prati, Liu, Perrewé, & Ferris, 2009).

Service organisations have expectations of customer-employee interactions with the aim of engendering customer satisfaction. Display rules are often in place that dictate how employees are meant to behave within a service encounter and which emotions are appropriate for employees to show (Ekman, 1973). Display rules are believed to increase strain on employees (e.g., Rohrmann, Bechtoldt, Hopp, Hodapp, & Zapf, 2011) and interacting with customers is thought to be psychologically draining (Walsh & Bartikowski, 2013). The literature on emotional labour has shown that service workers use a substantial number of emotion regulation strategies (Cho, Rutherford, & Park, 2013) to try and meet display rules (Daus & Ashkanasy, 2005). Emotional labour is described as having ‘human cost’ and the requirement of employees showing positive emotions can deplete resources, hinder task performance, and threaten well-being (Grandey, Rupp, & Brice, 2015).

This study addresses the need to focus on a broader working lifespan (Scheibe & Zacher, 2013) regarding emotional labour, age, burnout, and engagement in the service sector. Our main question is: are older workers not as good at emotional labour due to a decline in social competencies, as suggested by the deficit hypothesis? Or, as we argue, older workers have social competencies that facilitate emotional labour, thus reducing the likelihood of emotional exhaustion linked to “people work” (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002) and the potential for stress related absence and turnover. We expect this study to enhance understanding of the benefits of an ageing workforce in the context of service work, thus adding value to human resource practices, such as selection and recruitment, and training.

In order to investigate this, we first present the emotional labour concept and develop hypotheses on age and emotion regulation. In a second step, we introduce the concept of burnout and engagement and present hypotheses on the links between age, emotion regulation, and burnout/engagement. In a final step, we propose that emotion regulation strategies may mediate the relationship between age and burnout and engagement. The study is cross sectional; however, the design is not inappropriate as age cannot be reverse caused.

Emotional Labour StrategiesHochschild (1983) described two main types of emotional labour strategies: surface acting, where employees alter their outward expression to ‘fake’ emotions but their inner feelings remain unchanged, and deep acting, which involves employees changing their inner feelings to both feel and display the appropriate emotion. Grandey (2015) details how both field and lab based studies typically report surface acting as ‘bad’ for individual's well-being and deep acting as ‘good’ for job related outcomes. Most papers when discussing deep acting refer to situational deep acting (e.g., Hochschild, 1983), where the strategy is developed in the situation itself and the employee tries to influence their emotional response during the interaction. However, employees sometimes use anticipative deep acting by emotionally preparing for a situation prior to the interaction, e.g., a nurse thinking about a seriously ill patient, which may increase her ability to show an appropriate emotion or her feelings of sympathy, before the interaction starts, or where group talks and songs are used in meetings to help increase positive emotions (Nissley, Taylor, & Butler, 2002). In this paper we differentiate between such situational and anticipative deep acting (von Gilsa, Zapf, Ohly, Trumpold, & Machowski, 2014). While surface acting is a response-focused emotion regulation strategy with regulation after the emotion has already developed, deep acting is antecedent-focused with regulation before an emotion fully develops (Grandey, 2000; Gross, 1998a; Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011).

The faking of emotions, as seen in surface acting, is related to less pleasant customer interactions (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011). Customers can detect the superficial nature of surface acting leading to dissatisfaction with the service encounter (Zapf, 2002). Surface acting is shown to have direct links with turnover (Goodwin, Groth, & Frenkel, 2011; Scott & Barnes, 2011), indirect links to turnover through emotional exhaustion (Chau, Dahling, Levy, & Diefendorff, 2009), and a significant negative influence on organisational citizenship behaviours (Prentice, Chen, & King, 2013).

Service workers report more contentment with their authenticity and performance when they deep act rather than surface act (Brotheridge & Lee, 2002). Compared to surface acting, deep acting should serve to reduce the gap between expected (via display rules) and displayed emotions, and thus lead to more positive employee experiences. The aim of deep acting is to bring felt emotions in line with required emotions. Hülsheger and Schewe (2011) reported a positive relationship for deep acting and performance, and research into emotional labour generally agrees that only deep acting is related to enhanced task performance (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). Deep acting changes emotions into positive ones, which should mean fewer negative consequences for well-being (Gabriel, Daniels, Diefendorff, & Greguras, 2015; Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011).

A number of studies have looked at customer outcomes (Grandey, 2003; Groth, Hennig-Thurau, & Walsh, 2009; Hennig-Thurau, Groth, Paul, & Gremler, 2006) with results showing a negative relationship with surface acting, and a positive relationship with deep acting, on outcomes such as service quality, customer orientation, and loyalty intentions. These effects can be explained by the customers’ evaluation of how authentically they are being treated by the employee's emotional display (Yagil, 2012). Organisations could benefit from encouraging their employees to deep act rather than surface act (Bono & Vey, 2005).

Automatic emotion regulation (AER) is another type of emotion regulation described by Zapf (2002) and refers to those situations where emotions are triggered automatically by situational cues, e.g., a customer's friendly smile. This intuitive emotion regulation is effortless in comparison to surface and deep acting (also see Martínez-Iñigo, Totterdell, Alcover, & Holman, 2007). Diefendorff, Croyle, and Gosserand (2005) reported AER (also called ‘naturally felt emotions’ or ‘passive deep acting’) as distinct from surface and deep acting and describe how it is assumed to need the least mental energy and be less harmful than other emotional labour strategies (Scheibe & Zacher, 2013). More recently Hülsheger, Lang, Schewe, and Zijlstra (2015) discuss some similarities between deep acting and AER with both yielding authentic displays and linked to positive customer behaviour. Relatively little research has looked at AER and there is a call for more (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011; Wang, Seibert, & Boles, 2011).

Age and Emotion RegulationHochschild (1983) in her seminal paper argued that age is positively related to emotion management. This view was supported in Doerwald, Scheibe, Zacher, and Van Yperen's (2016) review of the literature, which reported moderate support for an age-related advantage in emotional competencies. However, there has been surprisingly little focus on age and emotion regulation in workplace studies. This is important because studies outside work often use groups of older people age 70+ which differ from the older worker group of 50+. In recognition of this, and of the age demographic changes mentioned above, researchers have called for studies investigating the relationship between age and emotion regulation (Mauno, Ruokolainen, & Kinnunen, 2013; Scheibe & Zacher, 2013).

In developmental literature, the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) (e.g. Carstensen, 2006) describes how motivation alters as people age. SST suggests as time becomes more limited, peoples’ goals change from focusing on gaining knowledge and information for the future, to more emphasis on emotional states and meaning. Urry and Gross (2010) and Charles and Carstensen (2007) detail how emotion regulation develops and is modified across the lifespan, with increased emotional control and variability in emotion regulation with age. It is suggested that older individuals may select certain emotion regulation strategies that gain or maintain other resources, with older individuals having lower negative affect, higher positive affect, and higher well-being. The association of age with emotional competence and the motivation to avoid or limit negative or high arousal situations is attributed to a shift in priorities as time is perceived to be more limited as people age, and to possible declines in physiological flexibility and cognition (Scheibe & Zacher, 2013). Although most developmental research is not directly studied in a work context, it has been proposed that age can be an influencing factor in the successful use of emotion regulation strategies at work (Lawrence, Troth, Jordan, & Collins, 2011). In a recent work based study, Johnson et al. (2013) report that older workers have better emotion control when faced with customer stressors. Likewise, Kim (2008) argues that older workers can control their emotions and their outward expression more successfully. The implication is that as workers age they are more able to select appropriate emotion regulation strategies to deal with customer service encounters. Doerwald et al. (2016)Doerwald et al. (2016) summarise lifespan theories, and changes in cognitions with age, and conclude that declines in fluid cognition may be mitigated by gains in crystallized cognition. They propose for older workers (between the ages of 40 and 65) that age related deficits and advantages may be optimally balanced, and accumulated knowledge and experience alongside increased motivation may serve to benefit older worker emotional competencies.

Deep acting could be easier for individuals who can draw on past experiences to help them feel the required emotion (Bono & Vey, 2007). With situational deep acting some workers may have more expertise and confidence in dealing with situations as they arise within an encounter and in showing the required emotion. Likewise, with anticipative deep acting, with experience employees may be able to anticipate situations and prepare before an encounter. As older workers have more experiences and emotional memories than younger workers, they may therefore be better able to engage in deep acting. Also, deep acting may promote autonomy and a sense of accomplishment, which could enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). As age has been positively linked to intrinsic motivation (Kooij, De Lange, Jansen, Kanfer, & Dikkers, 2011; Ng & Feldman, 2010), this may suggest older workers are more likely to engage in deep acting. von Gilsa et al. (2014) support this conjecture and report three motive categories for emotion regulation: pleasure, prevention, and instrumental. Instrumental motives are linked to surface acting, whereas pleasure motives are related to deep acting and AER. It is possible that pleasure motives and deep acting/AER will influence intrinsic satisfaction, which is more important to older than younger workers.

Studies have reported mixed findings on the age and emotional labour relationship, suggesting either a positive or no relationship exists between age and deep acting (Doerwald et al., 2016). Wang et al.’s (20**11) meta-analysis reported a marginal positive relation between age and deep acting of r = .07. More recent studies found somewhat higher effects. Adding the studies of Biron and van Veldhoven (2012), Cheung and Tang (2010), Cho et al. (2013), Dahling and Perez (2010), and Sliter, Chen, Withrow, and Sliter (2013) to the meta-analysis of Wang et al. leads to an updated sample size weighted correlation of r = .11 (12 studies, N = 3,763) indicating a dominance of studies finding a small positive effect of age on deep acting.1

There is less known about the relationship between age and AER but there are indications this will be related in a similar manner to deep acting. AER is about unconsciously regulating (as opposed to reacting to) one's emotions without deliberately making any effort. Mauss, Bunge, and Gross (2007) propose these strategies arise from overlearned habits, approaches learned in early life as well as sociocultural norms, and as we grow older we remember more positive emotions. Thus, older workers may use AER to their benefit. Dahling and Perez (2010) describe older adults as being more motivated to be positive, as proposed by SST (e.g., Carstensen, 2006), and show a positive link between age and AER, and Cheung and Tang (2010) report age is positively correlated with AER suggesting that older workers may have more ‘learnt’ responses which are automatic. Walsh and Bartikowski (2013) argue that being authentic in emotional display, i.e., deep acting (and therefore AER), would be less emotionally draining for older workers than not being authentic, i.e., surface acting, as older workers prefer to display authentic emotions. Given the expected association between age and deep acting and age and AER we hypothesise the following:

Age is positively related to situational and anticipative deep acting (H1a) and AER (H1b).

There are also limited and mixed findings reported on the age and surface acting relationship. Wang et al.’s (2011) meta-analysis reports a marginal negative relationship of r = -.08 between age and surface acting. Adding the studies of Biron and van Veldhoven (2012), Cheung and Tang (2010), Dahling and Perez (2010), and Sliter et al. (2013) to the meta-analysis leads to an updated sample size weighted correlation of r = -.10 (13 studies, N = 4383) indicating that most of the studies report a small effect size correlation for the age-surface acting relationship. Doerwald et al. (2016) reviewed the literature and concluded that older worker either use less or the same amount of surface acting as younger workers. Since the literature suggests that age and deep acting are linked, i.e., older individuals engage in more deep acting (e.g., Cho et al., 2013) the converse should also hold. That is, in the absence of the higher levels of deep acting seen in older workers, younger workers are more likely to surface act when faced with emotionally charged customer interactions. It is assumed that younger people who focus on knowledge-related goals (Carstensen, 1992) will fake emotions if they perceive conflicted goals between themselves and customers. Contrary to older people they could therefore prefer surface acting instead of deep acting. Given the argument above we hypothesise:

H1c: Age is negatively related to surface acting.

Burnout and EngagementBurnout is an individual reaction to high levels of emotional demands in service work (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Maslach, 1982). In terms of employee health, burnout is potentially one of the most damaging consequences of emotional labour (e.g., Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Zapf, 2002). Burnout comprises of three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, where employees feel emotionally drained; cynicism (also known as depersonalization), where employees have detached and negative attitudes towards other people or their work; reduced professional efficacy (also known as personal accomplishment), where there is a reduction in how effective employees feel at work.

According to Schaufeli, Martínez, Pinto, Salanova, and Bakker (2002) engagement is “a positive fulfilling, work related state of mind that is characterised by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (p. 74). Engagement appears to have positive outcomes for employees, such as low intentions to turnover and to quit (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), and high levels of organisational commitment (Richardson, Burke, & Martinussen, 2006) and employee performance (Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, 2005). Organisational benefits also result from employee engagement. For example, Viljevac, Cooper-Thomas, and Saks's (2012) detailed studies show engaged workers make better use of resources, and as such make fewer errors, giving better customer service, and achieving greater sales growth.

Interest in employee engagement continues to grow and, despite questions being raised about how engagement might differ from other constructs such as job satisfaction and commitment, research is increasing along with its use in practice (Viljevac et al., 2012). Indeed, whether or not studies determine that engagement is distinct from other constructs, or is related to them, it is clearly important for employees to feel engaged, and feelings of engagement are linked to outcomes such as job performance and turnover (Shuck, Ghosh, Zigarmi, & Nimon, 2012). Yalabik, Popaitoon, Chowne, and Rayton (2013) discuss the lack of consensus around the causes and consequences of engagement whilst detailing how studies are increasingly demonstrating that engagement is a unique construct that requires further study (Christian, Garza, & Slaughter, 2011). They conclude that researchers, practitioners, and governments all agree employee engagement is worthy of exploration due to its likely impact on performance.

Age, Burnout, and EngagementTwo meta-analyses have shown age is negatively related to burnout (Brewer & Shapard, 2004; Ng & Feldman, 2010). Brewer and Shapard (2004) report age is negatively related to emotional exhaustion. Ng and Feldman (2010) investigated all three burnout factors and report that older workers experience fewer problems with burnout, with age negatively related to emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.

Few studies have directly investigated the age and engagement relationship, although age was reported to be positively related to engagement by Yalabik et al. (2013) and Viljevac et al. (2012). Goštautaitė and Bučiūnienė (2015) reported evidence supporting a positive relationship and described how earlier studies using age as a control variable also reported a positive age-engagement relationship (e.g., Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006; Siu et al., 2010). Furthermore, positive associations with age are shown in constructs linked with engagement, such as job satisfaction (Birdi, Warr, & Oswald, 1995), work motivation (Ng & Feldman, 2010), and intrinsic motivation (Kooij et al., 2011), which suggests there will be age differences in work engagement. On the same lines, Christian et al. (2011) found a positive relationship for engagement with conscientiousness and positive affect, and research reports an increase in conscientiousness during adulthood (Staudinger & Bowen, 2010). Engagement is also related to emotional stability (Schaufeli, 2011) and with experienced emotions viewed as more predictable and less unstable with age (Charles & Carstensen, 2010), the evidence is suggesting a positive relationship between age and engagement. Given the expected links between age and engagement detailed here, we hypothesise:

H2: Age is positively related to engagement

Emotion Regulation, Burnout, and EngagementYagil (2012) reviewed the literature and summarised that surface acting and deep acting affect well-being in different ways, proposing that surface acting relates to burnout, whereas deep acting relates to work engagement. Surface acting is usually believed to require the suppression of negative emotions and the faking of positive emotions. Employees have to monitor and change their emotional display, which can reduce well-being and enhance emotional exhaustion and cynicism (von Gilsa & Zapf, 2013). The suppression of negative emotions increases physiological stress as a result of the activation of the cardiovascular and sympathetic nervous system (Gross, 1998a).

High emotion demands and surface acting are linked with emotional exhaustion, with no link found to deep acting (Biron & van Veldhoven, 2012). Similarly, surface acting, but not deep acting, is linked to turnover (Goodwin et al., 2011), increased somatic complaints, and depressed mood (Prati et al., 2009) and a worsening of affective state (Scott & Barnes, 2011). Studies also show that surface acting leads to increased strain (Grandey, 2003; Hülsheger, Lang, & Maier, 2010), and links to cynicism (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Wang et al., 2011). Given the links between surface acting and negative outcomes we hypothesise:

H3: Surface acting is positively related to exhaustion and cynicism

Deep acting is antecedent-focused which means emotion regulation takes place before an emotion develops with a view to changing a situation or changing the way in which the situation is perceived. During deep acting, individuals aim to align required feelings to true feelings leading to genuine displays of emotion. This can be achieved through the directing of attention to pleasurable thoughts to elicit the required emotion (attentional deployment) or by reappraising a situation to induce a required emotion (cognitive change) (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011).

Deep acting is related to greater well-being and improved affective state (Philipp & Schüpbach, 2010; Scott & Barnes, 2011), and studies have found either no or only a marginal relationship with exhaustion (e.g., Grandey, 2003; Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011; Martínez-Iñigo et al., 2007; Totterdell & Holman, 2003; Wang et al., 2011). Zapf (2002) proposed that deep acting should have a positive influence on personal accomplishment (professional efficacy), and studies have shown deep acting to be related to increased professional efficacy and affective well-being (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Brotheridge & Lee, 2002; Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011; Kim, 2008) and higher job satisfaction and task performance (Wang et al., 2011). Deep acting is thought to be related to increased professional efficacy as it suggests the customer is deserving of authentic expression, and positive feedback from the customer will increase feelings of personal efficacy (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). In line with the proposed positive effects of deep acting on professional efficacy, Schreurs, Guenter, Hülsheger, and van Emmerik (2014) and Yagil (2012) show a positive relationship of deep acting with engagement. There is limited evidence on AER but studies indicate it is associated with positive work outcomes, such as job satisfaction, lower psychological distress, and professional efficacy (Cheung & Tang, 2010; Cheung, Tang, & Tang, 2011). Given the links between deep acting and AER and positive work outcomes, we hypothesise:

H4a: Situational and anticipative deep acting are positively related to professional efficacy, and engagement.

H4b: AER is positively related to professional efficacy, and engagement.

Emotional Labour Mediates the Age and Burnout/Engagement RelationshipAustin, Dore, and O’Donovan (2008) propose that situational factors and personal resources influence the emotional labour-strain relationship. As discussed, one potential influence could be the age of the service worker, which may impact on the appropriate selection, and success, of emotion regulation strategies. Researchers have begun to explore the mediation effects linked with emotional labour strategies. For example, surface acting mediates between emotion rule dissonance (i.e., when there is disparity between felt emotions and those required to be shown to customers) and well-being (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011); engagement and burnout mediates emotion regulation and customer outcomes (Yagil, 2012); and positive affect mediates age and surface acting and AER (Dahling & Perez, 2010). There has however been very little investigation of the links between age, emotional labour, and outcomes, although deep acting was shown by Cheung and Tang (2010) to partially mediate between age and job satisfaction, thus supporting the proposal of a mediating influence of emotional labour between age and work outcomes.

Cheung and Tang (2010) studied job satisfaction and psychological health. To the best of our knowledge there is no published research looking at the potential mediating effect of emotional labour between age and burnout or engagement. This is relevant to the service sector, as burnout is one of the most damaging consequences of emotional labour (e.g., Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Zapf, 2002), whilst engagement is linked positively to beneficial outcomes such as customer satisfaction (e.g., Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002), job performance, and lower turnover (Shuck et al., 2012). Our study adds to the emerging literature on the mediation effects of emotional labour by investigating its influence on the relationship between age and burnout and engagement.

We hypothesise that emotional labour could be one factor that intervenes in the age-outcome relationship. We expect age to be related to the use of different emotional labour strategies, and for these emotional labour strategies to be associated with burnout and engagement. It is therefore possible emotion regulation is a mechanism through which age influences burnout and engagement outcomes. Given the anticipated negative effect of age and surface acting on exhaustion and cynicism, and the positive effect of age and deep acting on professional efficacy and engagement we hypothesise the following:

H5: Surface acting mediates the age and exhaustion, and age and cynicism, relationship.

H6: Deep acting and AER mediate the age and professional efficacy, and age and engagement relationship.

MethodSample and ProcedureWe examined our hypotheses in an age-heterogeneous sample of service employees from different organizations and occupational backgrounds in Germany. All participants were service employees with direct customer contact. To recruit participants, companies were contacted directly and asked for cooperation. Completing the questionnaire was voluntary, and all participants were assured that their data would remain confidential.

Of 1,028 questionnaires sent out, 444 were returned giving a response rate of 43.2%. None of the variables had more than 10% missing data, with the exception of surface acting, which had 78 items of missing data. For technical reasons, one of the research teams used a 4-item scale of surface acting resulting in 2 items missing. We considered these to be missing at random and used the MLR estimator in Mplus (Enders, 2013). Of the participants, 62% were female; age range 16-70, mean age 40.64 years (SD = 12.30). They worked in an array of service jobs (e.g., sales clerk, bank clerk, pharmacist, travel agent, hairdresser, and waiter), with 67.6% employed full-time. On average, participants had been working in their current position for 8.95 years (SD = 8.81, range 0-40 years).

MeasuresEmotion regulation strategies. Seventeen items assessed four emotion regulation strategies. Items were partly based on Brotheridge and Lee (2003), Gross (1998b), Totterdell and Holman (2003) and Tschan, Rochat, and Zapf (2005). A previous version of the scale was used by von Gilsa et al. (2014) with additional items developed for this research project. The items were rated on five-point scales, ranging from 1 (totally agree) to 5 (totally disagree). Scales were recoded with higher scores indicating that participants tend to use the strategy in question more often.

Surface Acting consisted of six items, measuring three aspects of surface acting, each assessed by two items: emotion amplification (e.g., “During the interaction I expressed emotions more strongly than I felt”), emotion suppression (e.g. “During the interaction I suppressed emotions which were not appropriate to the situation”), and emotion faking (e.g. “During the interaction I expressed emotions I did not feel”).

Anticipative Deep Acting comprised of four items assessing whether employees had prepared themselves for the approaching interaction (e.g., “Before beginning work, I prepared myself psychologically for the upcoming interactions”).

Situational Deep Acting included five items asking whether employees tried to experience emotions during interactions (e.g., “During the interaction I tried to see the positive aspects”).

Automatic Emotion Regulation (AER) consisted of two items asking about automatic emotions triggered by the situation (e.g., “I automatically felt the required emotions”).

Burnout. Burnout was measured with the German version (Büssing & Glaser, 1998) of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS; Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach, & Jackson, 1996). The survey comprises three subscales. Items were rated on five-point scales, ranging from 1 (I totally agree) to 5 (I totally disagree). Scales were recoded with higher scores indicating high exhaustion, cynicism, or professional efficacy.

Exhaustion relates to feeling overextended and drained by emotional work demands and was assessed by five items (e.g., “I feel emotionally drained from my work”).

Cynicism (or depersonalization) reflects indifferences or a distant attitude toward work and was assessed by five items (e.g., “I have become more cynical about whether my work contributes anything”).

Professional Efficacy (or personal accomplishment) encompasses occupational accomplishments and was assessed by six items (e.g., “At my work, I feel confident that I am effective at getting things done”). Note that a high score on this scale indicates high professional efficacy.

Work Engagement. Work engagement was assessed by the German 9-item short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, the UWES-9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Items were rated on seven-point scales, from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Higher scores indicate high engagement and the scale comprises three 3-item subscales.

Vigor is characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience (e.g., “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”).

Dedication refers to being strongly involved in one's work and experiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, and challenge (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my job”).

Absorption is characterized by being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in work (e.g., “I feel happy when I am working intensely”).

There were high intercorrelations between subscales (> .78), as previously reported (e.g., Bechtoldt, Rohrmann, De Pater, & Beersma, 2011). Therefore, we used a composite score of all subscales as recommended by Schaufeli et al. (2006).

DemographicsParticipants reported their chronological age and their job age (i.e., the total years worked in their current job).

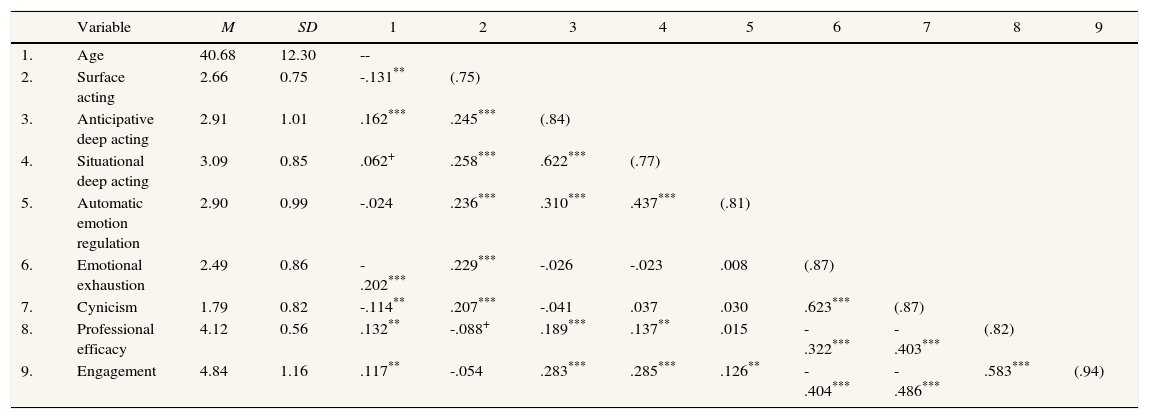

AnalysisTo test our hypotheses, we conducted mediation models for each emotion regulation strategy and dependent variable using Mplus 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010). As recommended, we focused on the significance of each indirect effect (Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, & Petty, 2011) and had a closer look at confidence intervals. We looked for residual direct effects of age on dependent variables to determine full or partial mediation. Since the direction of effects was predicted, all results report a one-tailed significance level of .05. Table 1 reports means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the study variables.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Study Variables.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Age | 40.68 | 12.30 | -- | ||||||||

| 2. | Surface acting | 2.66 | 0.75 | -.131** | (.75) | |||||||

| 3. | Anticipative deep acting | 2.91 | 1.01 | .162*** | .245*** | (.84) | ||||||

| 4. | Situational deep acting | 3.09 | 0.85 | .062+ | .258*** | .622*** | (.77) | |||||

| 5. | Automatic emotion regulation | 2.90 | 0.99 | -.024 | .236*** | .310*** | .437*** | (.81) | ||||

| 6. | Emotional exhaustion | 2.49 | 0.86 | -.202*** | .229*** | -.026 | -.023 | .008 | (.87) | |||

| 7. | Cynicism | 1.79 | 0.82 | -.114** | .207*** | -.041 | .037 | .030 | .623*** | (.87) | ||

| 8. | Professional efficacy | 4.12 | 0.56 | .132** | -.088+ | .189*** | .137** | .015 | -.322*** | -.403*** | (.82) | |

| 9. | Engagement | 4.84 | 1.16 | .117** | -.054 | .283*** | .285*** | .126** | -.404*** | -.486*** | .583*** | (.94) |

Note. Cross-sectional study (N = 444); p-values are one-tailed. Cronbach Alpha's are shown on the diagonal.

+p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

With regard to hypothesis 1, the expected negative relationship of age and surface acting, and the positive relationship of age and anticipative deep acting were found. However, there was only a marginally positive relationship of age and situational deep acting. There was no significant relationship for age and AER. Thus, there was partial support for H1a, no support for H1b, and strong support for H1c.

Age was negatively related to exhaustion and cynicism, and positively related to professional efficacy. As hypothesized in H2, age was positively related to engagement. We further tested the relationships of emotion regulation strategies and outcomes. Surface acting was positively related to exhaustion and cynicism, which supported H3. Anticipative and situational deep acting were positively related to professional efficacy and engagement, supporting H4a. AER was positively related to engagement, but not to professional efficacy, partly supporting H4b.

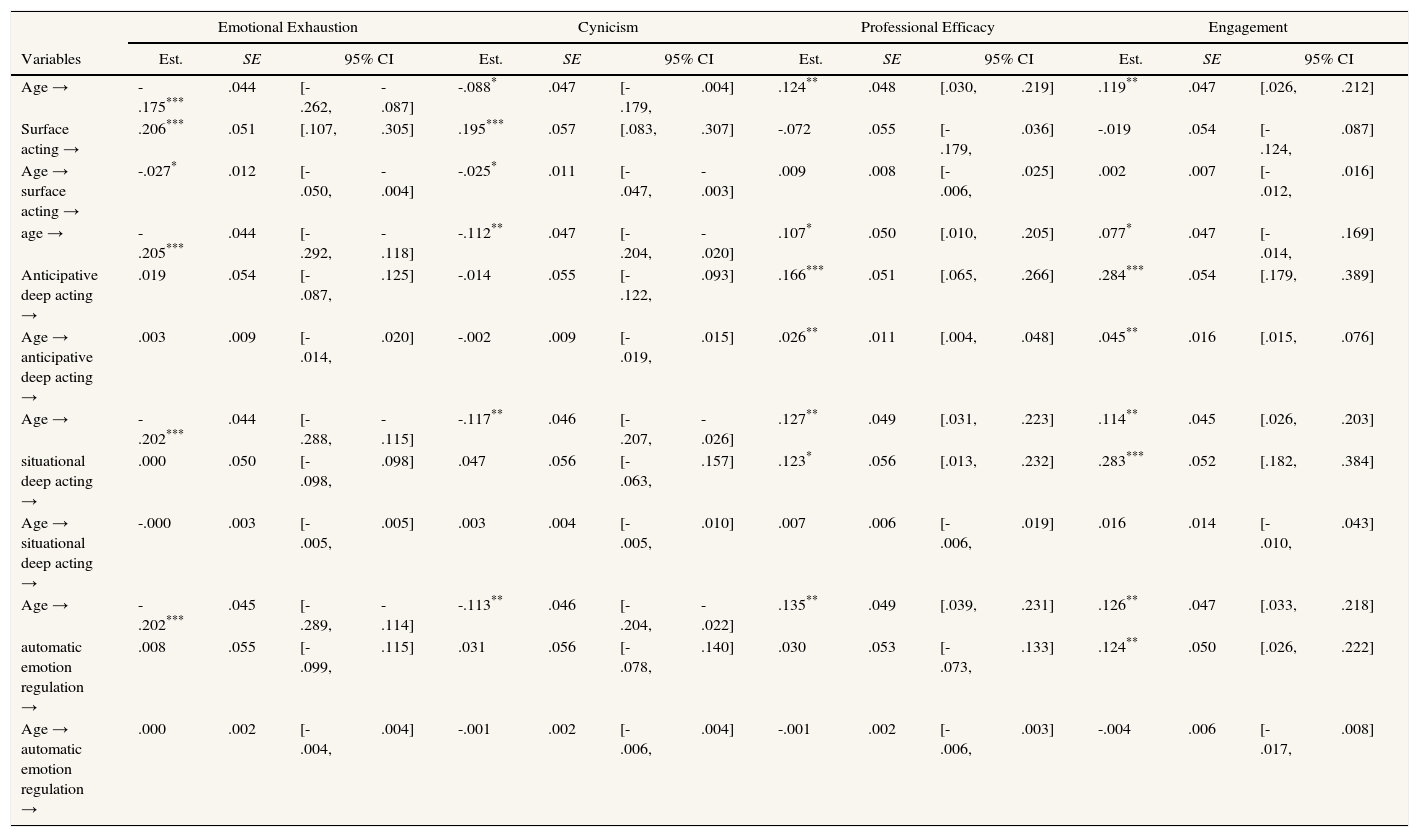

Table 2 shows the results of the mediation analyses. In support of H5, all hypothesized indirect effects were significant and corroborated by the 95% confidence interval excluding zero; age was negatively related to exhaustion and cynicism through surface acting. H6 proposed an indirect effect of age on professional efficacy and engagement through deep acting. There were two significant indirect effects, where the 95% confidence interval did not include zero; age was positively related to professional efficacy and engagement through anticipative deep acting. However, there was no significant indirect effect through situational deep acting or AER. Thus, H6 was only partly supported.

Results of Mediation Path Models.

| Emotional Exhaustion | Cynicism | Professional Efficacy | Engagement | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Est. | SE | 95% CI | Est. | SE | 95% CI | Est. | SE | 95% CI | Est. | SE | 95% CI | ||||

| Age → | -.175*** | .044 | [-.262, | -.087] | -.088* | .047 | [-.179, | .004] | .124** | .048 | [.030, | .219] | .119** | .047 | [.026, | .212] |

| Surface acting → | .206*** | .051 | [.107, | .305] | .195*** | .057 | [.083, | .307] | -.072 | .055 | [-.179, | .036] | -.019 | .054 | [-.124, | .087] |

| Age → surface acting → | -.027* | .012 | [-.050, | -.004] | -.025* | .011 | [-.047, | -.003] | .009 | .008 | [-.006, | .025] | .002 | .007 | [-.012, | .016] |

| age → | -.205*** | .044 | [-.292, | -.118] | -.112** | .047 | [-.204, | -.020] | .107* | .050 | [.010, | .205] | .077* | .047 | [-.014, | .169] |

| Anticipative deep acting → | .019 | .054 | [-.087, | .125] | -.014 | .055 | [-.122, | .093] | .166*** | .051 | [.065, | .266] | .284*** | .054 | [.179, | .389] |

| Age → anticipative deep acting → | .003 | .009 | [-.014, | .020] | -.002 | .009 | [-.019, | .015] | .026** | .011 | [.004, | .048] | .045** | .016 | [.015, | .076] |

| Age → | -.202*** | .044 | [-.288, | -.115] | -.117** | .046 | [-.207, | -.026] | .127** | .049 | [.031, | .223] | .114** | .045 | [.026, | .203] |

| situational deep acting → | .000 | .050 | [-.098, | .098] | .047 | .056 | [-.063, | .157] | .123* | .056 | [.013, | .232] | .283*** | .052 | [.182, | .384] |

| Age → situational deep acting → | -.000 | .003 | [-.005, | .005] | .003 | .004 | [-.005, | .010] | .007 | .006 | [-.006, | .019] | .016 | .014 | [-.010, | .043] |

| Age → | -.202*** | .045 | [-.289, | -.114] | -.113** | .046 | [-.204, | -.022] | .135** | .049 | [.039, | .231] | .126** | .047 | [.033, | .218] |

| automatic emotion regulation → | .008 | .055 | [-.099, | .115] | .031 | .056 | [-.078, | .140] | .030 | .053 | [-.073, | .133] | .124** | .050 | [.026, | .222] |

| Age → automatic emotion regulation → | .000 | .002 | [-.004, | .004] | -.001 | .002 | [-.006, | .004] | -.001 | .002 | [-.006, | .003] | -.004 | .006 | [-.017, | .008] |

Note. Different mediation path models for each emotion regulation strategy and each outcome; p-values are one-tailed.

+p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

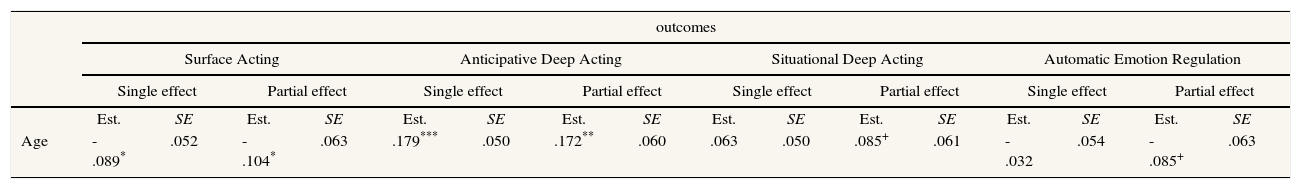

The present study focuses on the relationship between age and emotional labour strategies. In order to check if an individual's job experience plays the crucial role for the effects and not chronological age, we tested partial correlations controlling for the variable job age. Thus, in Table 3 we report the adjusted effects of age. The reported relationships between age and emotional labour strategies remain consistent even when job age is controlled for, thus demonstrating the importance of life experience above job experience in determining the use of emotional labour strategies. Indeed, the influence of age on surface acting, situational deep acting, and AER tends to increase when job age is controlled.

Comparison of Direct Effects and Partial Effects Controlled for Job Age.

| outcomes | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Acting | Anticipative Deep Acting | Situational Deep Acting | Automatic Emotion Regulation | |||||||||||||

| Single effect | Partial effect | Single effect | Partial effect | Single effect | Partial effect | Single effect | Partial effect | |||||||||

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Age | -.089* | .052 | -.104* | .063 | .179*** | .050 | .172** | .060 | .063 | .050 | .085+ | .061 | -.032 | .054 | -.085+ | .063 |

Note. Different models for each emotion regulation strategy; p-values are one-tailed.

+p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

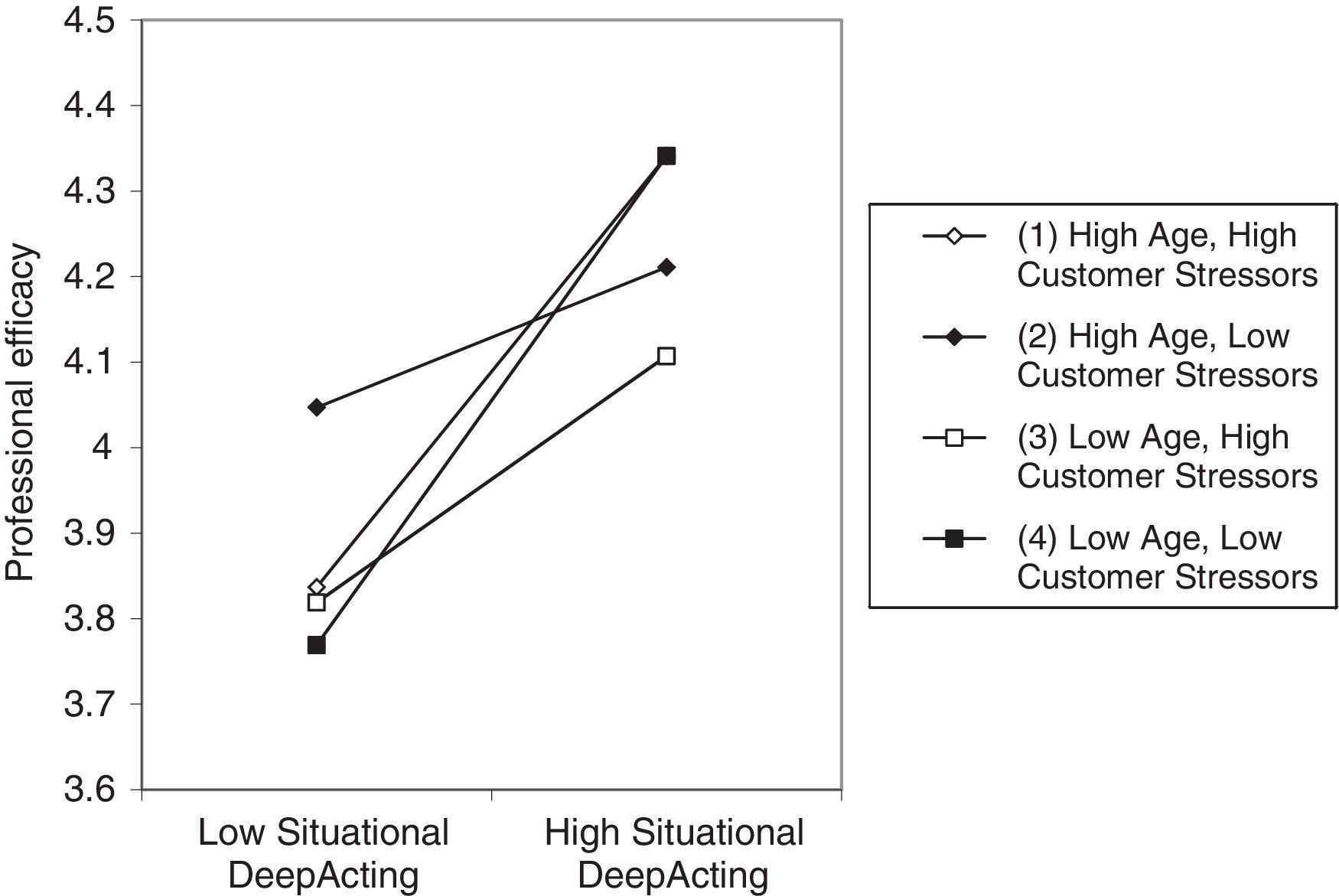

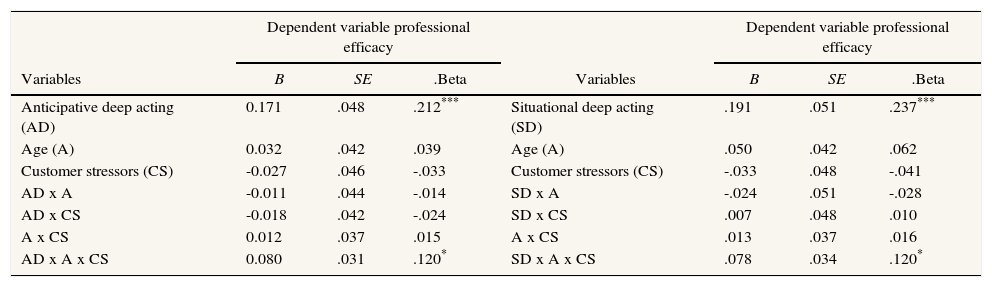

Furthermore, in order to find out if older workers are better at emotional labour and feel more professional due to the use of good strategies, we performed interaction analyses in Mplus with professional efficacy as the dependent variable. The reason was that quantity says little about quality. We assumed that if older workers have a stronger relationship between emotion regulation and professional efficacy this would imply that these strategies were applied more successfully. To check whether there was an interaction between age and emotional labour strategies in general or whether an interaction effect existed only if a customer interaction was not easy to manage and customer stressors were high, we additionally applied an overall measure of the customer-related social stressor scale of Dormann and Zapf (2004) in the version used by Dudenhöffer and Dormann (2015). The scale measures four stressors (disproportionate customer expectations, verbally aggressive customers, disliked customers, and ambiguous customer expectations) relating to negative customer interactions and comprised 15 items, which were slightly adapted for the present study. We performed 2-way-interactions and 3-way-interactions for each emotional labour strategy and professional efficacy (cf. Johnson et al., 2013).

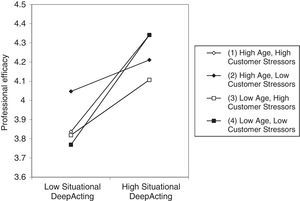

Results showed no significant 2-way-interaction. Thus, we found no evidence that the beneficial effect of positive emotion regulation strategies or the detrimental effect of negative emotion regulation strategies in general might differ between older and younger workers. But two out of four 3-way-interactions were significant. Here the expected pattern occurred for high customer stressors: both young and old workers reported little professional efficacy when levels of deep acting were low. However, when levels of deep acting were high older employees reported more efficacy (see Table 4 and Figure 1; the figure shows the results for situational deep acting. The figure for anticipative deep acting is almost identical).

Results of Three-way Interactions of Deep Acting, Age, and Customer Stressors on Professional Efficacy.

| Dependent variable professional efficacy | Dependent variable professional efficacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | SE | .Beta | Variables | B | SE | .Beta |

| Anticipative deep acting (AD) | 0.171 | .048 | .212*** | Situational deep acting (SD) | .191 | .051 | .237*** |

| Age (A) | 0.032 | .042 | .039 | Age (A) | .050 | .042 | .062 |

| Customer stressors (CS) | -0.027 | .046 | -.033 | Customer stressors (CS) | -.033 | .048 | -.041 |

| AD x A | -0.011 | .044 | -.014 | SD x A | -.024 | .051 | -.028 |

| AD x CS | -0.018 | .042 | -.024 | SD x CS | .007 | .048 | .010 |

| A x CS | 0.012 | .037 | .015 | A x CS | .013 | .037 | .016 |

| AD x A x CS | 0.080 | .031 | .120* | SD x A x CS | .078 | .034 | .120* |

Note. Different models for each emotion regulation strategy; p-values are one-tailed.

+p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

If customer stressors were low older workers showed a lesser dependency on the use of deep acting. Compared to younger employees they reported more professional efficacy when levels of deep acting were low and less professional efficacy when levels of deep acting were high.

DiscussionThis study shows that in Germany, older workers use more anticipative deep acting and less surface acting than younger employees. They also showed a tendency to use more situational deep acting when job age was controlled. This is in line with the updated meta-analyitical findings of Wang et al. (2011) as reported above and provides support for SST by confirming the views of Charles and Carstensen (2007) and Urry and Gross (2010) that older workers may use positive emotion regulation strategies developed through life experience. The study shows that emotional competencies identified in non-work contexts are also evident in the workplace. Thus, our results are in line with the review of Doerwald et al. (2016), which concludes that older workers show equal or slightly better functionality of most emotional competencies. Furthermore, older workers are more engaged with their work, more confident in their abilities to do the job, and experience less exhaustion and cynicism than younger employees.

Overall we find that older workers are better in terms of using positive (adaptive) emotion regulation strategies and are more engaged and less burnt out, or are no different to younger workers. This therefore suggests the deficit hypothesis does not hold, since we find no evidence that older workers are worse than younger workers. We suggest the opposite, as older workers are better than younger workers in some areas of emotional competencies. Therefore, older workers may be valuable assets particularly in customer facing roles.

It is of interest that age is more strongly associated with anticipative deep acting and only marginally with situational deep acting. One explanation for this is prior experience of older workers in ‘having seen it all before’. We assume that anticipative deep acting is used if complications during the interactions are anticipated. Life experience helps older workers know how to prepare in advance for encounters in order to deal with it successfully. This suggests that prior experience increases the likelihood of actively preparing for an emotional encounter and may also influence feelings of competence in dealing with a situation again. Situational deep acting is not prepared in advance and relies on the ability and confidence to deal with situations as they arise. Whilst both types of deep acting are positive emotion regulation strategies, with age comes a greater ability to prepare for encounters in advance as a technique to manage potentially difficult situations. Older workers may particularly prefer this strategy, as it increases the chance of positive and reduces the chance of negative encounters as found for everyday interactions (Charles & Carstensen, 2007; Charles & Piazza, 2009); this is in line with SST. However, they also seem to use more situational deep acting.

The lack of association between AER and age, which becomes marginally negative when job age is controlled, is difficult to interpret. A small number of studies have reported links between age and AER (Cheung & Tang, 2010; Dahling & Perez, 2010). We did not find AER to be clearly linked to age, or associated with negative outcomes (as with surface acting). However, AER is associated with the positive outcome of engagement (as with deep acting but to a lesser degree) and not with professional efficacy. AER is not intentional but automatically induced by the situation. First, situations in which emotions are elicited automatically may be valued less in terms of professional efficacy. Second, AER is strongly related to positive situations which trigger positive emotions. Older workers may be better able to positively influence social situations. At the same time because of their competences they might more often have to deal with problematic customer interactions. These processes may neutralize each other.

Our study supports former research in showing links between surface acting and increased feelings of exhaustion and cynicism (e.g., Bono & Vey, 2005; Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011; Wang et al., 2011). The analysis revealed surface acting is only marginally associated with reduced feelings of professional efficacy (supporting Brotheridge & Lee, 2002) and not related to lower engagement. The results therefore add to research by confirming the links between surface acting and exhaustion and cynicism and showing that surface acting has minimal detrimental effects on professional efficacy. This is important for employee well-being and for effective customer service since faking emotions is related to customer dissatisfaction (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011; Zapf, 2002). These findings suggest that older workers could enhance service encounters through their less frequent use of surface acting.

In line with former studies, deep acting is associated with positive outcomes (e.g., Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Yagil, 2012). The current study extends knowledge in the area by investigating two types of deep acting and demonstrates that both anticipative and situational deep acting are linked to feelings of professional efficacy and engagement. This suggests that both strategies are positive for employee well-being and potentially for customer satisfaction. Given the links described above between age and anticipative deep acting, the use of this deep acting strategy may be one reason why older workers are less burnt out and more engaged, a proposition that we explored further via mediation analysis.

Age influences the use of emotion regulation strategies and has a positive impact on well-being. According to our findings, age predicts less burnout and more engagement through the use of the emotion regulation strategies surface and anticipative deep acting. Partial mediation reflects the fact that there are, of course, further competencies, e.g., stress management strategies (Johnson et al., 2013), that may also be responsible for age-burnout relations. Notably, no mediation was found for situational deep acting or AER. The mediation role of surface and anticipative deep acting reflects the importance of emotion regulation strategies on the well-being of employees. Part of the explanation as to why age is linked to positive work outcomes is that older workers are able to select emotion regulation strategies that are least harmful to health. Younger workers use surface acting more and as such are more emotionally exhausted and indifferent to work. Whereas older workers use more anticipative deep acting and are therefore more engaged and feel more effective. Whether burnout or engagement is experienced is partially explained through the type of emotion regulation strategy used. This is in line with the review of Doerwald et al. (2016), who conclude that occupational well-being of older worker benefits of better emotional competencies with increasing age. Our study contributes to their call for more research of the effect of age on emotional competencies and occupational well-being.

Compared to other studies, this study is novel in investigating and reporting that relationships between age and emotional labour strategies remain consistent even when job age is controlled for. This suggests that life experience, and not just job experience, is important when determining the use of emotional labour strategies. This is in line with previously reported findings where job age was shown to have little impact on the use of stress management strategies and burnout (Johnson et al., 2013) or conflict management and burnout (Beitler, Machowski, Johnson & Zapf, 2016), again suggesting that it is life experience that is more important than job experience. Practically this is important, if life experience means older individuals have the appropriate skills in terms of emotion regulation to match the requirements of the service sector, then previous job related experience may be less important than life experience when matching applicants to job requirements. It is interesting to note that controlling for job age tends to increase rather than decrease age-emotion regulation relationships. This suggests that short-term learning effects on the job are clearly distinct from lifelong experiences when it comes to emotion regulation. Future studies should seek to investigate both chronological age and job age to better understand their relative impact.

This study further adds to the literature as it investigates older workers, who are generally younger than the older individuals commonly studied in life span development studies (Scheibe, Spieler, & Kuba, 2016). Thus, when we report emotional advantages of older workers we show that such advantages occur within the working population and are not restricted to much older individuals who are less likely to still be in work.

Furthermore, additional analyses did not find a 2-way-interaction between emotion regulation strategies and age on professional efficacy. However, there are two out of four significant 3-way-interactions between emotion regulation strategies, age, and customer stressors on professional efficacy for anticipative and situational deep acting. High professional efficacy means a positive experience in using this emotion regulation strategy in customer interactions. If customer stressors are high – implying that a situation is difficult and challenging – there is a difference between younger and older workers when levels of deep acting are high, indicating that older workers report more professional efficacy in this case. We believe this implies older workers use these strategies more effectively than the younger ones.

Practical ImplicationsOlder workers experience greater obstacles in open competition in the labour market than any other employee group, often as a result of stereotypical attitudes (Parry & Harris, 2011). However, our findings show that older workers possess skills beneficial to customer service organisations and should be seen as valuable resources. It makes good business sense to recruit and retain older workers, particularly given the ageing population. Socio-emotional competencies are especially important in the service sector because of frequent customer interactions. But in other industries it is also helpful that older workers are better in socio-emotional competencies. For example, in interactions between different employees and between employee and leader, good socio-emotional competencies are likely to be helpful.

Training is essential to help employees deal successfully with emotionally charged customer interactions. Emotional labour skills can be taught, and more positive emotion regulation strategies promoted to benefit employees. Employees at risk, for example those who use surface acting most often, should be identified and offered emotion regulation training. Through role-playing emotional labour strategies in typical customer interactions, employees could learn to distinguish between surface and deep acting (Goodwin et al., 2011). Older workers can be utilised as mentors, coaches, and trainers to help junior employees learn positive emotion regulation techniques such as the beneficial anticipative deep acting used successfully by older workers.

Customers are also likely to benefit from such emotional labour training as previous studies linked deep acting to more positive customer outcomes (Groth et al., 2009; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2006). Reducing the negative qualities of emotional labour may result in even more positive outcomes for organisations, with a potential reduction in intentions to quit and turnover, resulting in better service quality, increased production, lower replacement costs and improved performance as tacit knowledge is retained within organisations (Walsh & Bartikowski, 2013).

Limitations and Future ResearchSelf-report measures are criticised for their likelihood of eliciting socially desirable responses (Roberts, MacCann, Matthews, & Zeidner, 2010) but self-report assessment does not systematically distort findings (Paunonen & LeBel, 2010). For emotional labour, self-report is a practical option of measurement since it cannot be observed externally. The cross-sectional nature of this study has limitations, such as not being able to consider the emotion regulation abilities of workers who have opted out of work, which can lead to the ‘healthy worker effect’ and the lack of insight such a research design can bring to our understanding of causal relationships. However, given the study hypotheses are informed by non-work based literature supporting older individuals’ emotional abilities, the healthy worker effect is not likely to be the only explanation for the findings, and since our primary concern is on the influence of age, and age cannot be reverse caused, there is less need to establish causal effect via longitudinal designs. Johnson et al. (2013) discuss generational effects as present in longitudinal and cross-sectional designs, meaning sample differences cannot be interpreted as pure age effects in either research design, and argued that although cross-sectional designs have limitations they are relevant for the study of age effects. Ideally, future research should use longitudinal cohort-sequential studies to disentangle generational and ageing effects, although this is costly and time consuming (Scheibe & Zacher, 2013).

Future research may also benefit from the use of diary studies to capture data on actual emotional interactions near the time they occur, and reduce retrospection bias (Iida, Shrout, Laurenceau, & Bolger, 2012). This could also allow the integration of additional potentially relevant work variables that may serve as resources or constraints.

Future research could also include measures relating to employees’ subjective sense of future time to allow more detailed exploration of how SST relates to employee experiences and behaviour at work. Whilst we report the current study is in line with SST theory we did not specifically measure this.

Furthermore, it is necessary to address the potential influence of cultural characteristics on organizational behaviour (Brodbeck, Frese, & Javidan, 2002) in a sample of German service employees. Beitler et al. (2016) discuss that Germany ranks very high on sociocultural dimensions such as assertiveness, uncertainty avoidance, and high on performance orientation (Brodbeck & Frese, 2007; Brodbeck et al., 2002) and report that despite the cultural differences between Germany, China, and the USA similar age effects are reported for conflict management. Similarly, our results about emotion regulation are in line with studies conducted in different cultural contexts. For example, the negative relationship of age and the use of surface acting was found in a UK sample (Holman, Chissick, & Totterdell, 2002) and in different US samples (e.g., Dahling & Perez, 2010; Prati et al., 2009; Sliter et al., 2013). The positive relationship of age and the use of deep acting is in line with the study of Dahling and Perez (2010) in the US, the study of Cheung and Tang (2010) in Hong Kong, and the study of Cho et al. (2013) in South Korea. In conclusion, situational characteristics appear to play a superior role in customer interactions than cultural aspects and we believe our study findings are likely to be generalisable to other countries and cultures, although this should be confirmed through future research.

Finally, this study reports age links to anticipative deep acting, and anticipative deep acting mediating between age and engagement, yet no such associations were found for situational deep acting. It is proposed therefore that the distinction made in this study between different types of deep acting (situational and anticipative) may help to explain the mixed findings reported for age and deep acting (Doerwald et al., 2016). Future studies should consider looking at these different types of deep acting in more detail when investigating the potential impact or function of deep acting.

ConclusionThis study focuses on the research gap regarding emotional labour, age, burnout, and engagement and addresses issues raised by Scheibe and Zacher (2013) following their study on emotion regulation, stress, and well-being in the workplace. In addition to reporting on direct links between variables and confirming previously reported associations, for example as seen in Wang et al's (2011) meta-analysis, the study adds to the literature on the mediation effects of emotional labour by investigating its influence on the relationship between age and burnout and engagement. The study also adds to the literature in a number of other ways, for example by: reporting on the lack of association between AER and age and showing AER to be linked to engagement but not to professional efficacy; demonstrating links between two types of deep acting (anticipative and situational) and professional efficacy and engagement, and between age and anticipative deep acting; demonstrating the relationships between emotional labour and age remain even when controlling for job age, thus indicating the importance of life (and not only job) experience; demonstrating the emotional advantages of older working individuals not commonly studied in life span studies.

The relationships demonstrated in this study between age, deep acting, surface acting, and burnout and engagement have important practical implications for employees and their managers, organisations, and customers. Both the age of the employee and the type of emotion regulation strategy they use influence well-being. Our findings suggest that employees should be discouraged from surface acting when deep acting is possible. In particular, younger employees should be offered training to enable them to increase their use of deep acting. The findings also support Diefendorff, Stanley, and Gabriel's (2015) proposal that older employees should be appreciated more for using positive emotion regulation strategies and the ability to better establish an initial positive emotional experience for customers than their younger colleagues.

Financial SupportThe work was supported by VW Foundation's ‘Individual and Societal Perspectives of Ageing’ (No. II/83 183). The study was part of a research project “Key Potentials of Older Employees in the Service Sector” in which psychologists from Germany (D. Zapf, S. Machowski, L. Beitler, U. Koevenig, S. Scherer) and the UK (S. Johnson, L. Holdsworth, H. Hoel) collaborated.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.