High-risk breast lesions constitute a heterogeneous group of pathologies, some of which are considered cancer precursors. For a correct histological diagnosis, it is necessary to standardize the pathological criteria, whereby the identification of atypia is very important, since its presence increases the risk of carcinoma and determines the management of these lesions. The treatment, in most cases, is surgical excision or vacuum-assisted biopsy, and clinicopathological correlation in a multidisciplinary committee is deemed necessary. We review the different entities, the frequency of underestimation of malignancy in diagnostic biopsies, the main differential diagnoses and the different therapeutic categories.

Las lesiones mamarias de alto riesgo constituyen un grupo heterogéneo de patologías incluidas en la categoría diagnostica B3, algunas consideradas precursoras de carcinoma, Para un correcto diagnóstico histológico es necesario estandarizar los criterios patológicos, siendo muy importante la identificación de atipia, ya que su presencia incrementa el riesgo de carcinoma y determina el manejo de estas lesiones. El tratamiento recomendado, en la mayoría de los casos, es la exéresis quirúrgica o la biopsia asistida al vacío, considerándose necesaria la correlación clínico-patológica en un comité multidisciplinar. Revisamos las características histológicas de las distintas entidades, la frecuencia de infraestimación de malignidad en las biopsias diagnósticas, los principales diagnósticos diferenciales y las distintas modalidades terapéuticas.

High-risk breast lesions (HRLs) are mostly epithelial proliferations affecting the terminal duct lobular unit.1 They are associated with a high risk of developing subsequent cancer, although with different frequencies depending on the entity. The overall incidence ranges from 3 to 12% of breast biopsies with a mean of 6%.2–5

Correctly identifying high-risk breast lesions is a major challenge for the pathologist in the appropriate management of patients.6 In order to properly interpret a breast biopsy, the pathologist requires clinical and radiological information about the lesion.7

For routine diagnosis in incisional biopsies of the breast (core needle biopsy, CNB), the classification of the Royal College of Pathologists is useful. Lesions of uncertain or high-risk malignant potential are included in category B3, which also includes other non-epithelial proliferative lesions (Table1). Subsequently, two subcategories, B3a and B3b, have been established based on the presence or absence of associated atypia. The underestimation of malignancy in these lesions in breast biopsy ranges from 9 to 35% depending on the different entities.8 The presence of atypia increases the risk of malignancy.9

Diagnostic characteristics of breast biopsies.

| Pathological Report of breast biopsies | |

|---|---|

| B1 | Normal tissue or unsatisfactory for diagnosis |

| B2 | Benign lesion:Columnar cell changes, Columnar cells hyperplasia, Fibroadenoma, Usual ductal hyperplasia, Ductal ectasia, Sclerosing adenosis, apocrine metaplasia, steatonecrosis, abscess. |

| B3 | Uncertain malignant potential lesion:Radial scar, papillary lesion, fibroepithelial lesion, Flat epithelial atypia, lobular neoplasia, Atypical ductal hyperplasia, Mucocele, Undetermined vascular lesion, Other infrequent lesions. |

| B4 | Atypical lesion suspicious of malignancy |

| B5a | Intraductal carcinoma |

| B5b | Invasive carcinoma |

| B5c | Carcinoma: in situ/invasive not evaluable |

It is important to establish standardized diagnostic criteria for these lesions as this helps to increase diagnostic reproducibility and intra- and inter-observer agreement.10

Frequently, some of these proliferative lesions may coexist in the same biopsy, which can hinder risk assessment and patient management. The presence of atypia is the prevailing criterion for treatment.11

In recent years, the incorporation of alternative non-surgical and more cost-effective techniques, such as vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB), has allowed the removal of more tissue. This has contributed to the fact that not only the diagnosis but also the treatment of many B3 lesions has changed, with the increasing use of VAB2,4,5,12 rather than surgical excision (Table2). In any case, it is recommended that the decision to manage these lesions be taken in a multidisciplinary context.

Recommendations for management of uncertain malignant potential lesions (B3) in the NHSBSP.

| B3 lesion diagnosed by 14 g core needle biopsy (CNB) or vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB), | Recommended approach | Suggested follow-up if no malignancy is identified on vacuum-assisted excision (VAE) |

| Atypical intraductal epithelial proliferationLobular neoplasm (classic, non-pleomorphic).Flat atypia.Radial scar with atypia.Papillary lesions with atypia.Mucocele-like lesion with atypiaRadial scar or papillary lesions without atypia.Fibroepithelial lesion with stromal hypercellularity.Mucocele-like lesion without atypia.Other: spindle cell lesions, microglandular adenosis, adenomyoepithelioma | Excision/thorough sampling by EAV, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Excision/thorough sampling by VAE, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Excision/thorough sampling by VAE, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Excision/thorough sampling by VAE, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Diagnostic surgical excision Excision/thorough sampling by VAE, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Excision/thorough sampling by VAE, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Surgical excisionExcision/thorough sampling by VAE, equivalent to 4 g of breast tissue.Surgical excision | Annual follow-up. MammographyRoutine screening only. |

HRLs include a range of entities, some of which show similar molecular and immunophenotypic characteristics, and fall within what is described as the pathogenic pathway of low-grade breast neoplasia.6

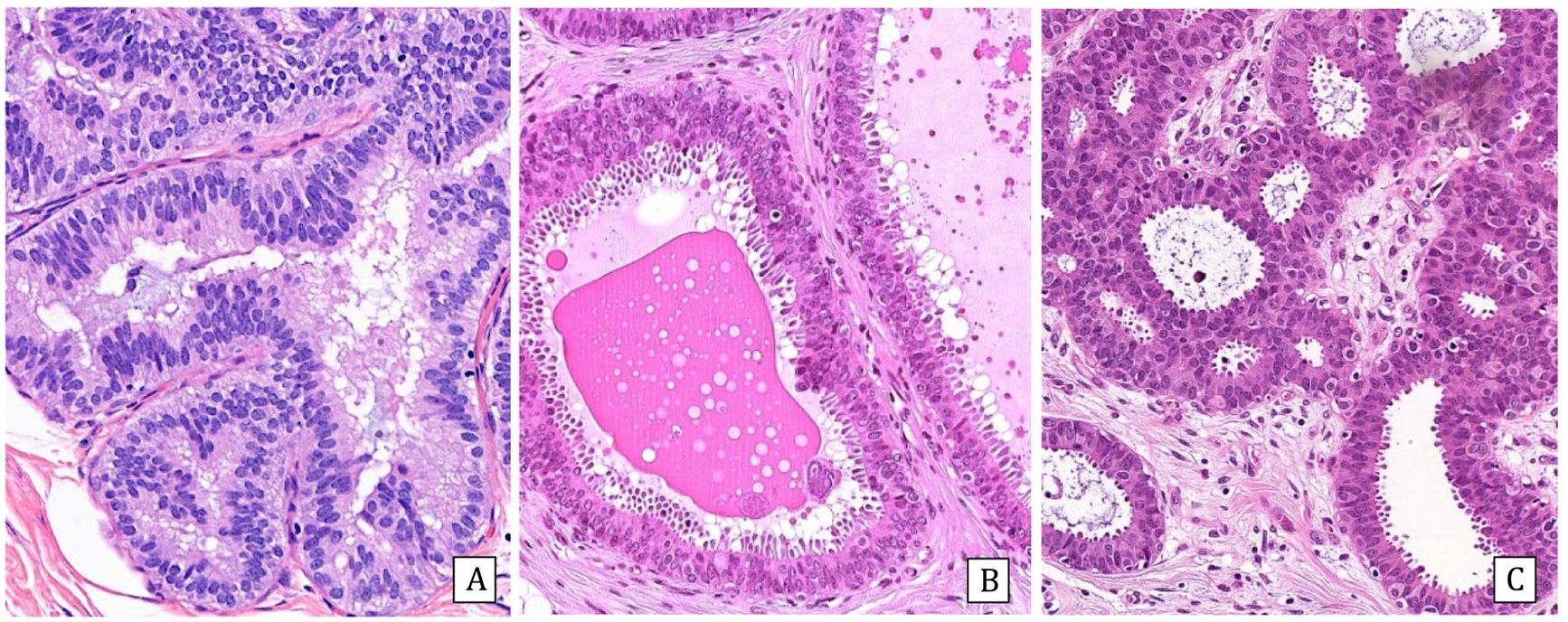

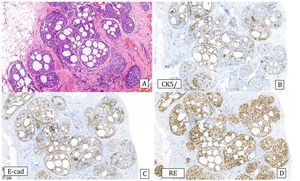

Fibroepithelial and papillary lesions are addressed in other chapters of this issueFlat atypiaColumnar cell lesions include three entities: columnar cell lesion and columnar cell hyperplasia, classified as B2, and columnar lesion with atypia or flat atypia (FEA) (Fig.1). The latter is considered high-risk B3b.

Incidence: FEA is identified in 1–8% of breast biopsies13,14 and in up to 16% of B3 lesions.15 It can be associated with atypical ductal hyperplasia and lobular neoplasia.2,6

Radiologically it presents with microcalcifications on screening mammography.

Histologically, FEA is characterized by the presence of dilated, basophilic acini, with one or more layers of cells with apical decapitate secretion and monomorphous rounded nuclei with obvious nucleoli. Loss of polarization with respect to the basement membrane is observed. They can form outlines of micropapillae but never extensively. Many of the ducts present secretions and/or endoluminal microcalcifications. It may be associated with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate located in the perilesional stroma.

Immunohistochemistry: All columnar lesions, even without atypia, are intensely and diffusely positive for estrogen receptors (ER). Cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6) is negative in all of them.

Differential diagnosis:

- Apocrine metaplasia: The ducts are also distended and show decapitated secretion but ER are negative.

- Columnar cell hyperplasia: the cells are more elongated, perpendicular to the basement membrane and the nucleolus is not evident.

- Usual ductal hyperplasia (UDH): bridging or cleft formation is observed at the periphery of the lumen of a duct, without stiffness and some cellular variability. ER and CK5/6 show heterogeneous positivity.6,16

- Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) / low-grade intraductal carcinoma (LGIDC): Rigid bridges and arcades with a cribriform or micropapillary pattern and uniform cellularity are observed. In these cases, the morphology is what prevails, as the immunohistochemistry is identical to that of flat atypia (ER+++ and CK5/6 negative).

- Flat intraductal carcinoma: This is a high nuclear grade lesion as opposed to flat atypia. It is associated with comedo necrosis.

Treatment: Removal of microcalcifications with VAB is considered adequate.8,18

Evolution: FEA is a lesion with a low risk of progression to carcinoma if observed purely, but sometimes it is associated with other higher-risk precursor lesions. When evaluating low-grade invasive carcinomas and invasive tubulo-lobular carcinomas, a significant association with flat atypia has been observed. The risk of developing carcinoma is 1.5 times higher than in the normal population6 and the underestimation of malignancy in the CNB with respect to the surgical specimen ranges between 2–17%,2,17,18 but by performing radio-pathological correlation drops to 2–3%.14

Atypical ductal hyperplasia/low-grade intraductal carcinomaIncidence: It is observed in 3–15% of diagnostic CNBs and increases to 10–15% in VABs 14. It accounts for up to 35% of B3 lesions.15

Presentation: Most present with radiological microcalcifications and less frequently as densities or distortions.2

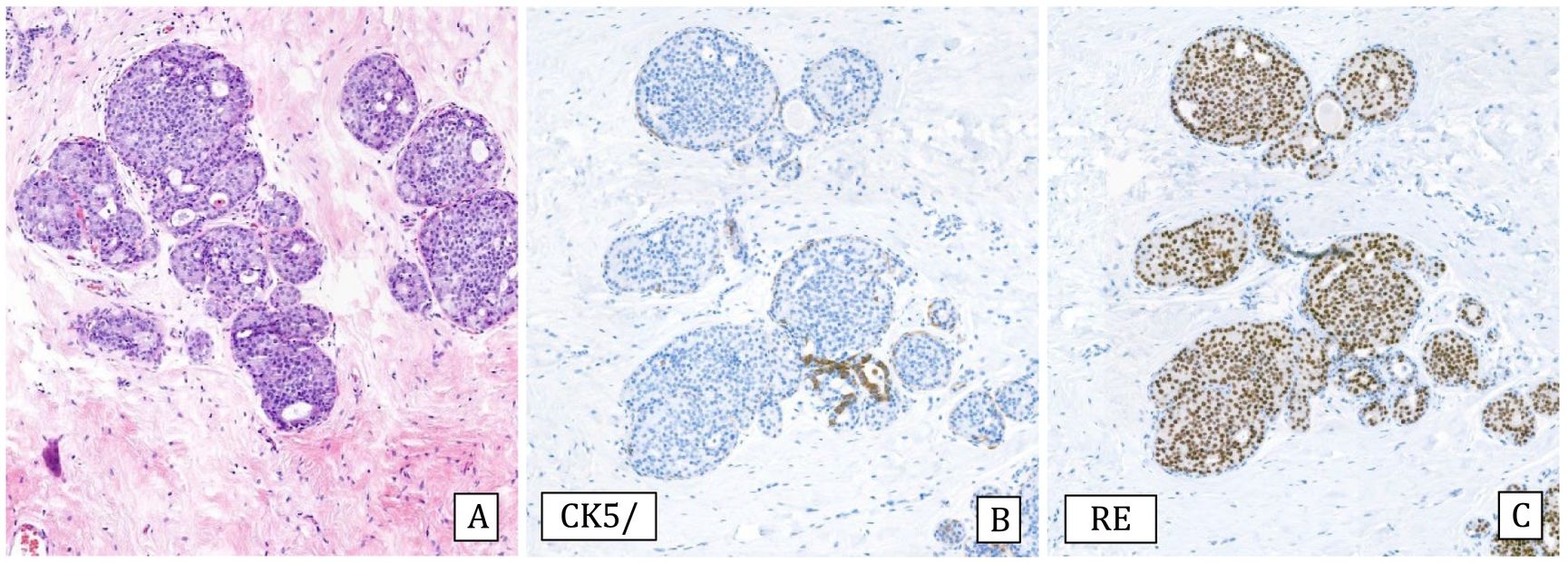

Histology: Intraductal proliferation of atypical cells with monomorphous round nuclei and architectural atypia in the form of rigid bridges, arcades, cribriform or micropapillary pattern. Polarization of the cells toward the lumen of the ducts is observed. These changes completely or incompletely affect the affected spaces.

Immunohistochemistry: Both entities express ER intensely and diffusely and CK5/6 is negative (Fig.2).

Differential diagnosis:

- The difference between ADH and LGIDC is determined by the extent of the lesion, which is referred to as LGIDC when the lesion measures more than 2 mm or affects more than two ducts.1 When in doubt, it is advisable to diagnose ADH. Some experts recommend using the term Atypical Intraductal Proliferative Lesion for borderline cases in CNB.14

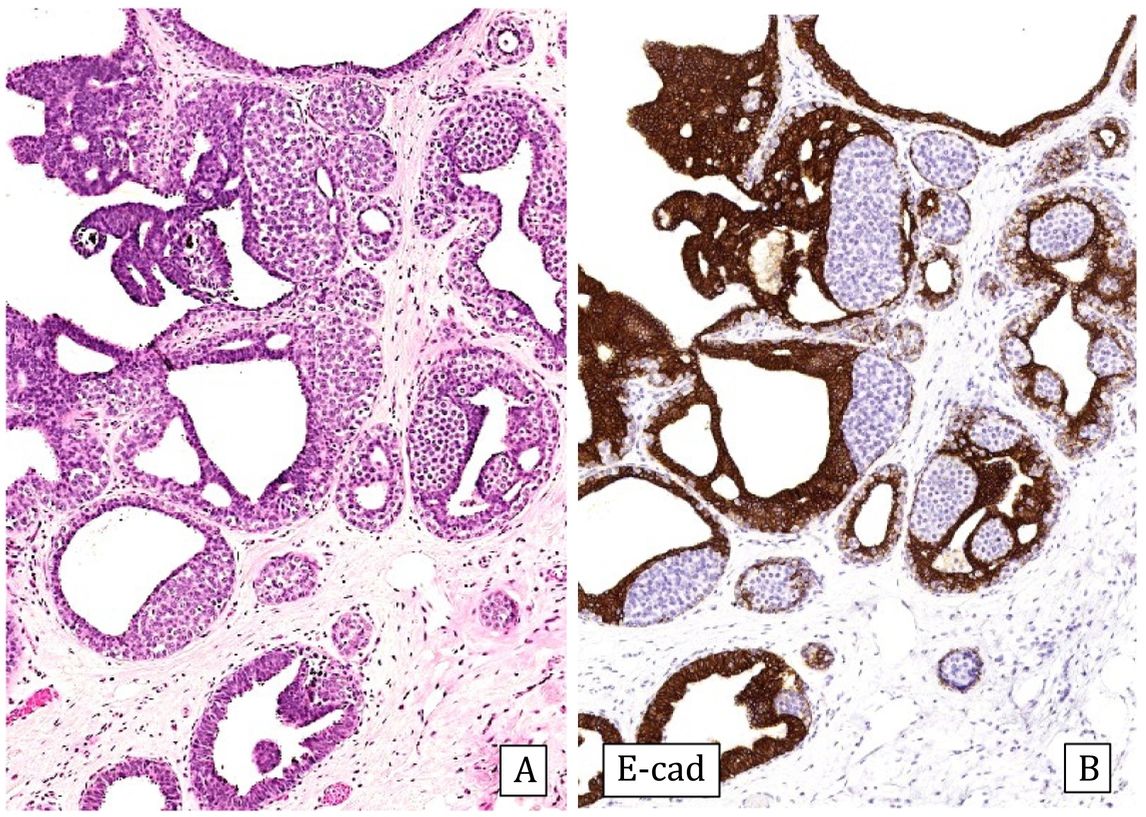

-Collagenous spherulosis is an epithelial-myoepithelial proliferation with a cribriform pattern that can mimic ADH, especially if associated with lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). In spherulosis the spaces are surrounded by myoepithelial cells and contain basement membrane material. The immunohistochemical study in these cases with p63 and/or myosin confirms the presence of myoepithelial cells surrounding the ductal spaces. E-cadherin staining can demonstrate associated LCIS19 (Fig.3).

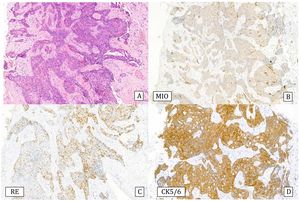

Collagenous spherulosis associated with lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) (20x).

A) Hematoxylin–Eosin: pseudo-cribriform pattern.

B) Cytokeratin 5/6: positive expression covering spherical cells (CK5/6).

C) E-cadherin: loss of expression in the LCIS component (E-cad).

D) Estrogen receptors: Diffusely and intensely positive expression in LCIS (ER).

- In micropapillary UDH (gynecomastoid hyperplasia) the micropapillae have a broad base that narrows toward the lumina where the papillae cells tend to cluster together and are smaller. CK5/6 and ER are heterogeneously positive in these cases.16 In ADH/IDC the base of the papillae is narrow a broad bulbous apex.

- Adenoid cystic carcinoma, although morphologically it may mimic LGIDC or ADH, is characteristically a triple-negative tumor and variably expresses myoepithelial markers. The c-Kit and Myb is positive.20

- Invasive cribriform carcinoma: the tumor nests have an irregular architecture. No myoepithelial lining is observed around the ducts whereas in ADH and LGIDC myoepithelial cells are observed around the ducts.

Treatment: Surgical excision.8 In cases of ADH with very small microcalcifications that could be completely removed by vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) or in elderly patients, the decision not to perform surgery may be considered.21

Evolution: numerous studies have shown that patients with ADH have a 3 to 5 times higher risk of developing both homolateral and contralateral carcinoma than in the normal population. The absolute risk of cancer is 15% (3.7–30%), affecting both breasts. The latency time after the diagnosis of ADH in a surgical biopsy, until the development of carcinoma, is 8.3 years.22 The underestimation in the CNB of patients undergoing surgery ranges from 0–80%,14,18 with an average of 29% for LGIDC and 9% for invasive carcinoma.21 The rate of underestimation seems to be related to the caliber and number of cylinders obtained in the biopsy.2,14

Patients with LGIDC undergoing surgery alone show a 2% annual risk of developing invasive carcinoma, which is reduced by half if they receive radiotherapy and even more if they receive hormone therapy. Thus, at 25 years of age, the risk of developing carcinoma is at least 25%, and can increase to 50–60% if the lesion is multifocal and with multiple calcifications. Of the patients who progress to carcinoma, 25% develop intraductal carcinoma and 75% develop invasive carcinoma, either lobular or no special type.23

Lobular neoplasiaThis term includes two entities: atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), classical type (C-LCIS)1.

Incidence: C-LCIS: It is identified in 0.5–1% of benign biopsies, 22% of B3 lesions,15 accounting for 0.5%–4% of all breast biopsies.14,24,25 In reduction mammaplasty the incidence is 0.04–1.2%.25 It is usually found in premenopausal women and can be multicentric and bilateral.26

Presentation: They frequently present as an incidental finding in biopsies or excision for other pathologies (4.7–34%).25

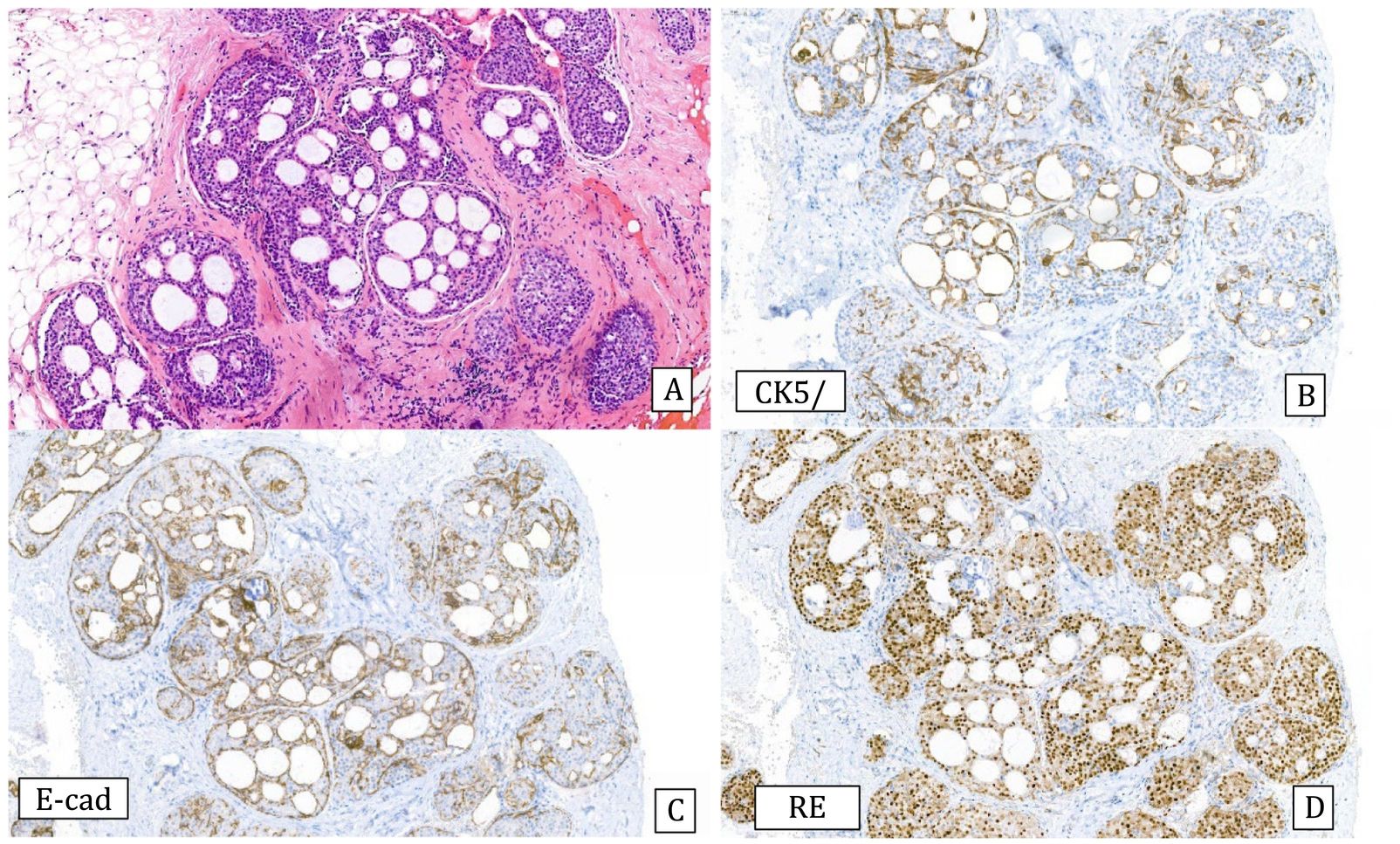

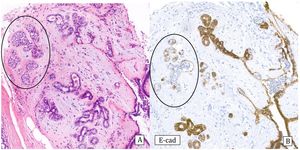

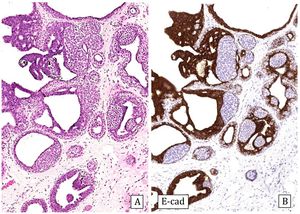

Histology: Monomorphous proliferation of discohesive epithelial cells predominantly involving the lobules. The cell borders are not very sharp. Cells may contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles and/or signet ring configuration. Proliferating cells are classified as A or B depending on whether they are very small or monomorphous or discretely larger. ALH does not show lobular distension and the proliferation occupies less than 50% of the lobule (Fig.4), while in C-LCIS there is distension of the lobules and terminal ducts that can present a pagetoid pattern and the lesion occupies more than 50% of the lobule (Fig.5). The two lesions can coexist.27 Differentiating between them can be very difficult in CNB, thus some authors recommend using the terminology of lobular neoplasia in these cases.12

Immunohistochemistry: C-LCIS is typically positive for ER and progesterone receptors and negative for HER2. Lobular neoplasia is negative for E-cadherin27 and expresses cytoplasmic P120 catenin.27,28 In some cases, aberrant expression of E-cadherin can be observed in the form of weak and incomplete membrane staining, cytoplasmic or dot-like staining.28 In these situations it is useful to also perform beta-catenin, which is usually negative or expressed in a granular pattern.

Differential diagnosis:

- Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC): when it colonizes foci of sclerosing adenosis, C-LCIS can simulate invasive carcinoma: Myoepithelial markers are very useful in these cases.

- Cribriform LGIDC: When LCIS colonizes a collagenous spherulosis, it can simulate intraductal carcinoma. Positive myoepithelial markers around lumina and negativity for E-cadherin of intercalating cells are useful for diagnosis.19

- Solid LGIDC: Focally, it is possible to identify glandular differentiation or a cribriform pattern and E-cadherin is strongly positive.25

- Florid LCIS: It is not well established in which category this entity is included. Some authors recommend classifying it as B4. It frequently presents as radiological microcalcifications. The proliferating cells are of type B, but remain monomorphous. It usually affects large ducts, which show central comedo necrosis and microcalcifications.28

- Pleomorphic LCIS also affects large ducts and is included in category B5a, requiring surgical treatment.2 It presents in post-menopausal women in the form of microlcacifications. The cells are large and pleomorphic, with hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm is eosinophilic, apocrin-like and may also contain vacuoles. It is also associated with comedo necrosis and microcalcifications and involves large ducts. It may coexist with classic-typeLCIS, which guides the diagnosis. Immunophenotypically both entities show the same features as C-LCIS (E-cadherin negative and cytoplasmic P120), but the pleomorphic variant may be hormone receptor negative and overexpress HER2.28

Genetics: Both ALH and all LCIS subtypes are genetically similar, showing 16q deletions and 1q gains with a similar pattern of chromosomal aberrations. Between 60–80% of LCIS show somatic mutations of CDH1 and PIK3CA28 as observed in ILC.

Treatment: Currently, ALH and C-LCIS are treated as a benign disease and do not require surgical treatment, unless associated with another lesion that requires it or there is radio-pathological discordance.8,29 However, there are discordant opinions in that regard and some authors have recommended surgery for LCIS, due to the high incidence of underdiagnosis of malignancy in CNB.30 Hormonal treatment has also been recommended in LCIS.26 In pleomorphic and florid variants, surgical excision is recommended, since the underestimation of malignancy is increased in these entities (25–40%).8,31

Evolution: ALH is associated with a 4–5 times higher risk of developing subsequent carcinoma. Most of them develop cancer with a very good prognosis.The risk in patients diagnosed with C-LCIS is 9–10 higher than in the normal population. An annual risk of 2% has been observed.26 The underestimation of LCIS malignancy in CNB ranges from 0–38%,28 while it is lower for ALH.32 With a good radio-pathological correlation, the incidence of underestimation of malignancy can be as low as 3%.14

Pathway of low-grade neoplasia

It has been observed that FEA, ADH, LGIDC,LN andinvasive low-gradetubulo-lobular carcinomas share immunophenotypic, molecular and genetic characteristics that differ from those of invasive high-grade carcinoma. FEA has been shown to show the same genetic alterations (loss of heterozygosity) as LGIDC and low-grade invasive carcinomas.23 Recurrent loss of 16q, 17q and 3p has been observed.33 On the other hand, more than 70% of patients with LGIDC or ADH also show loss of 16q, 17q or 3p34 or gain of 17q, 1q or 16p.23,34 Additionally, it has also been postulated that EZH2 expression in the epithelium of ADH could identify an increased risk of developing carcinoma.23 Some more recent work has identified copy number gains in CCN1 and ESR1 and losses in CDH1 in both FEA and LGIDC. With all these findings, a low-grade neoplasia pathway is currently established that would start with FEA and progress, on the one hand, to ADH or LGIDC, or also to LN and ILC.6

Radial scar/complex sclerosing lesionThey are essentially similar lesions. Classically, the term radial scar (RS) has been reserved for lesions smaller than 10 mm, and complex sclerosing lesion (CSL) has been used for larger lesions or when the biopsy does not clearly identify the fibroelastotic center or when they do not show a clearly radial configuration. The reality is that the two names are often used interchangeably.2

Incidence: 1–2% of total CNBs14 and 8% of B3 lesions.15

Presentation: Radiological distortion with or without microcalcifications.

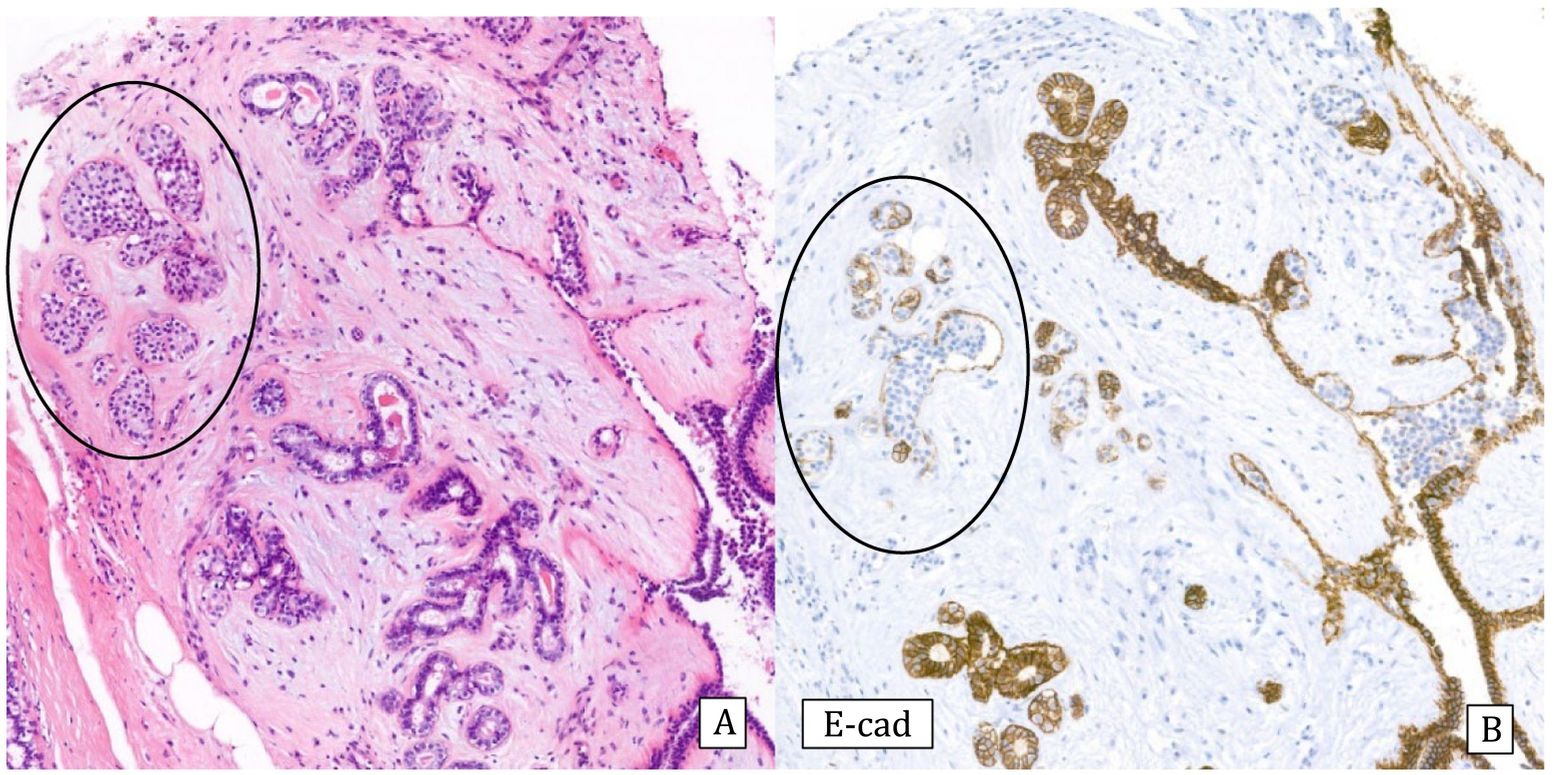

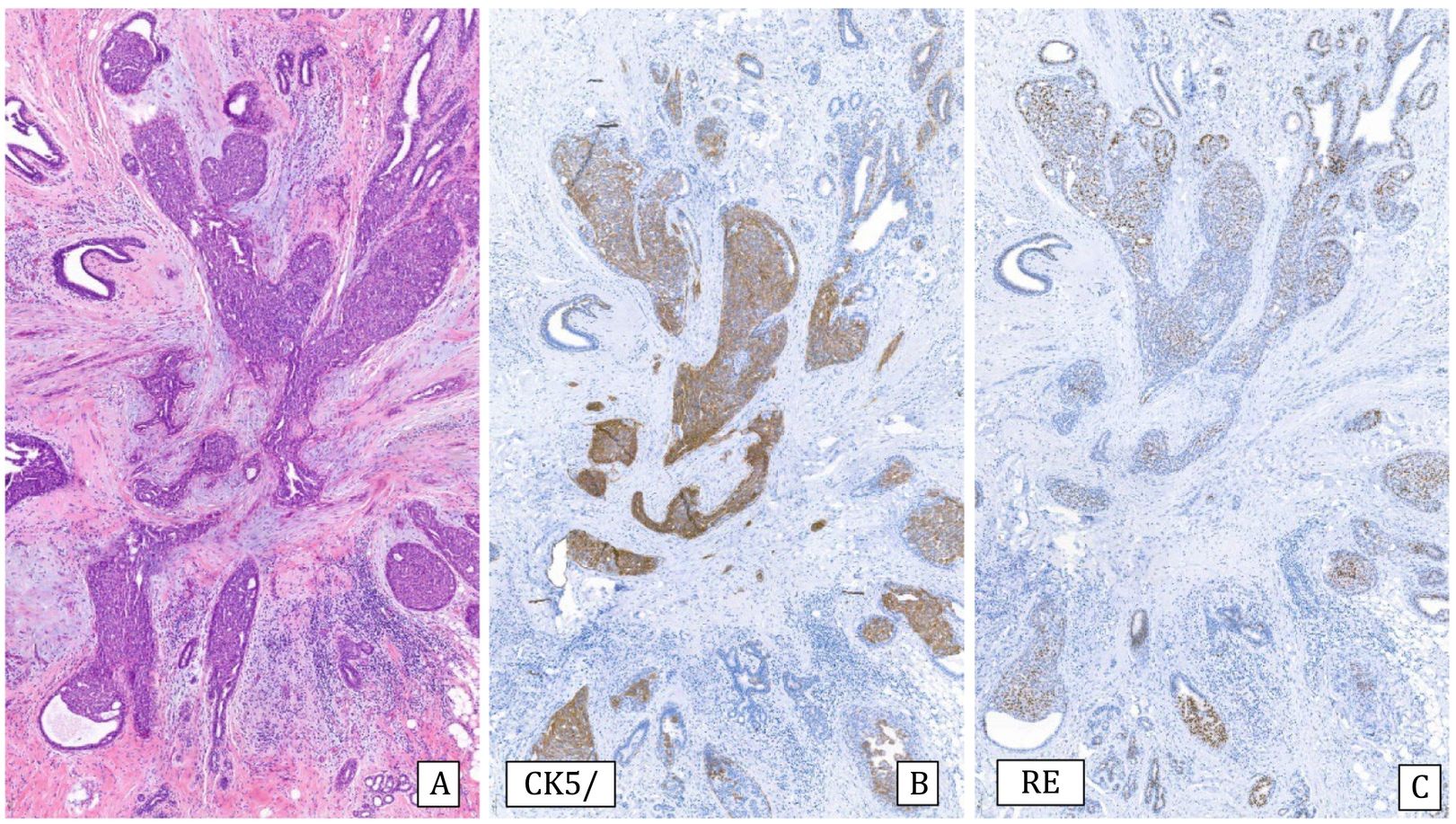

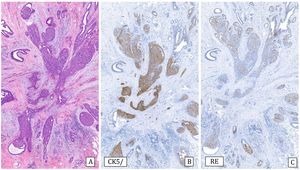

Histology: It is characterized by a lesion of radial configuration with a central area with fibroelastotic stroma containing trapped benign tubules. The periphery shows dilated ducts with fibrocystic changes and foci of adenosis. It can be associated with epithelial proliferation in the form of UDH or micropapillomas, but also ADH or IDC or lobular neoplasia can be observed2 (Fig.6).

Complex sclerosing lesion with usual ductal hyperplasia (10x).

A) Hematoxylin–Eosin: radial lesion with sclerosed center and ductal epithelial proliferation in the periphery.

B) Cytokeratin 5/6: heterogeneous expression (CK5/6).

C) Estrogen receptors: Heterogeneous expression (ER).

Immunohistochemistry: Some discontinuity of myoepithelial cells in the central tubules is accepted.

Differential diagnosis:

- Tubular carcinoma: In this type of invasive carcinoma, desmoplastic stroma and total and complete absence of myoepithelial lining are observed.

- Sclerosing adenosis: It shows a lobulocentric pattern and absence of fibroelastotic stroma, always with the presence of myoepithelial cells.

-Low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma (LGASC). Some CSL or fibroepithelial lesions may show adenosquamous proliferation (ASP), which is characterized by compact ducts with squamous and glandular features in a spindle cell stroma. Genetic sequencing studies have shown that they are clonal entities. These lesions can be associated with LGASC, but it is difficult to differentiate between these changes35 as both are triple negative and show positivity for CK5/6 and p63 with absence of myoepithelial cells. The difference mainly lies in the extent of the changes and the degree of infiltration of the adjacent tissue.

Genetics: Loss of 16q23,34 similar to low-grade neoplasms has been observed.

Treatment: In small lesions without atypia, complete excision by VAB is considered sufficient because of the low risk of underestimation of malignancy.8 Some authors have advocated monitoring in small lesions without atypia and radio-pathological correlation. In lesions with atypia, surgical excision is recommended.36

Evolution: Patients with RS have a 1- to 2-fold higher risk of developing breast cancer than the general population. The underestimation of malignancy in biopsy ranges from 9% to 36% depending on the presence of atypia.2,12,37,38 In lesions without atypia, the incidence of malignancy drops to 1–2%.14 It has also been observed that a larger caliber of biopsies and the number of cylinders obtained decreases the incidence of malignancy.39

MucoceleIncidence: It is a very rare entity.

Presentation: Most present as radiological microcalcifications40 and occasionally as a mass, or may be observed incidentally.41

Histology: Mucocele-like lesions are characterized by mucin-distended ducts and cysts with rupture and extravasation within the stroma.41,42 Typically the mucin lakes are irregular, variable in size and usually acellular, but occasionally sloughed bands of epithelium may be observed within them. Microcalcifications are frequently observed. It can be associated with benign cysts, UDH, columnar lesion, ADH (13–63%), IDC or invasive carcinoma.

Differential diagnosis:

- Cysticystic hypersecretory lesions41: In these, the endoluminal material is eosinophilic and may simulate colloid.

- Stromal mucin-containing breast lesions, such as nodular mucinosis, myxoma, myxoid myofibroblastoma or fibroepithelial lesions.41,44

- Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma: A very rare entity that manifests as a hyperlobulated mass consisting of mucin. The epithelial lining shows cells with mucin or micropapillae. It is triple negative and expresses CK5/6 and CK7.45

- Invasive mucinous carcinoma: It can be very difficult to distinguish a mucocele-like lesion with sloughed epithelial fragments from true neoplastic nests. If the sloughed epithelium is very sparse, shows no atypia and there is no associated IDC, it is most likely a benign lesion. Mucinous carcinoma nests do not show myoepithelial lining.41,44 It has also been observed that the mucin of mucinous carcinoma shows vascular neoformation, which can be demonstrated with CD31, while in mucocele it is not identified.46

Treatment: Currently, in cases without atypia, complete removal of microcalcifications with VAB12 is recommended, and in cases with atypia some authors recommend surgical excision.29,40

Evolution: The underestimation of malignancy for cases with atypia ranges from 19–33%, being ostensibly lower (0–5%) in cases without atypia.42–44

Infrequent lesionsOther lesions that are classified as B3 are adenomyoepithelioma, microglandular adenosis, atypical apocrine adenosis, infiltrating epitheliosis, granular cell tumor, spindle cell lesions and vascular lesions that are difficult to classify by CNB.12

Atypical apocrine adenosis: A very rare entity (0.4% of benign breast lesions by CNB) presenting in post-menopausal women. It consists of a proliferation of acini lined by cells of round nuclei of variable sizes with a prominent nucleolus and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The main differential diagnosis is with apocrine intraductal carcinoma, and to rule it out, some authors recommend excision.47 Genetic analysis has revealed some similarity between some of these lesions and apocrine carcinoma, suggesting that they may represent precursor lesions.34

Microglandular adenosis (MGA): An even rarer entity characterized by a proliferation of small glandular structures lined by cuboidal cells that are distributed in a pseudoinfiltrative pattern affecting adipose tissue. The glandular lumina contain PAS-positive dense eosinophilic material. Persistent ducts and lobules appear surrounded, but not compressed by proliferation.48 Immunohistochemically these lesions are triple negative and show no myoepithelial lining, although the presence of basement membrane with expression of type-IV collagen and laminin around the tubules is observed. Tubules express S100 protein while epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and GCDFP-15 are negative. The most important differential diagnosis is low-grade invasive carcinoma and tubular carcinoma, which express hormone receptors. Atypical microglandular adenosis shows a more complex architecture and more cytologic atypia. Immunophenotypically it has the same characteristics as MGA. Sequencing studies have shown that this is a clonal lesion. It has been associated with triple-negative carcinomas, especially adenoid cystic carcinoma and acinar cell carcinoma in the context of low-gradetriple-negative tumors.49 Adenosis can also mimic MGA but the lobular-centric pattern and the presence of myoepithelial cells aid in the diagnóstico.

Molecular studies have shown P5350 mutations and have also recognized this entity as a precursor of high-grade breast carcinoma,34 sharing identical genetic aberrations 8q + (75%) 1q + (60%) 17q+, 20q + 1p–, 8p– and 13p–16q– (< 30%).

Evolution: MGA shows an incidence of underestimation of malignancy of 25%, being a high-risk lesion. For this reason, surgical treatment is deemed the most appropriate type of treatment.51

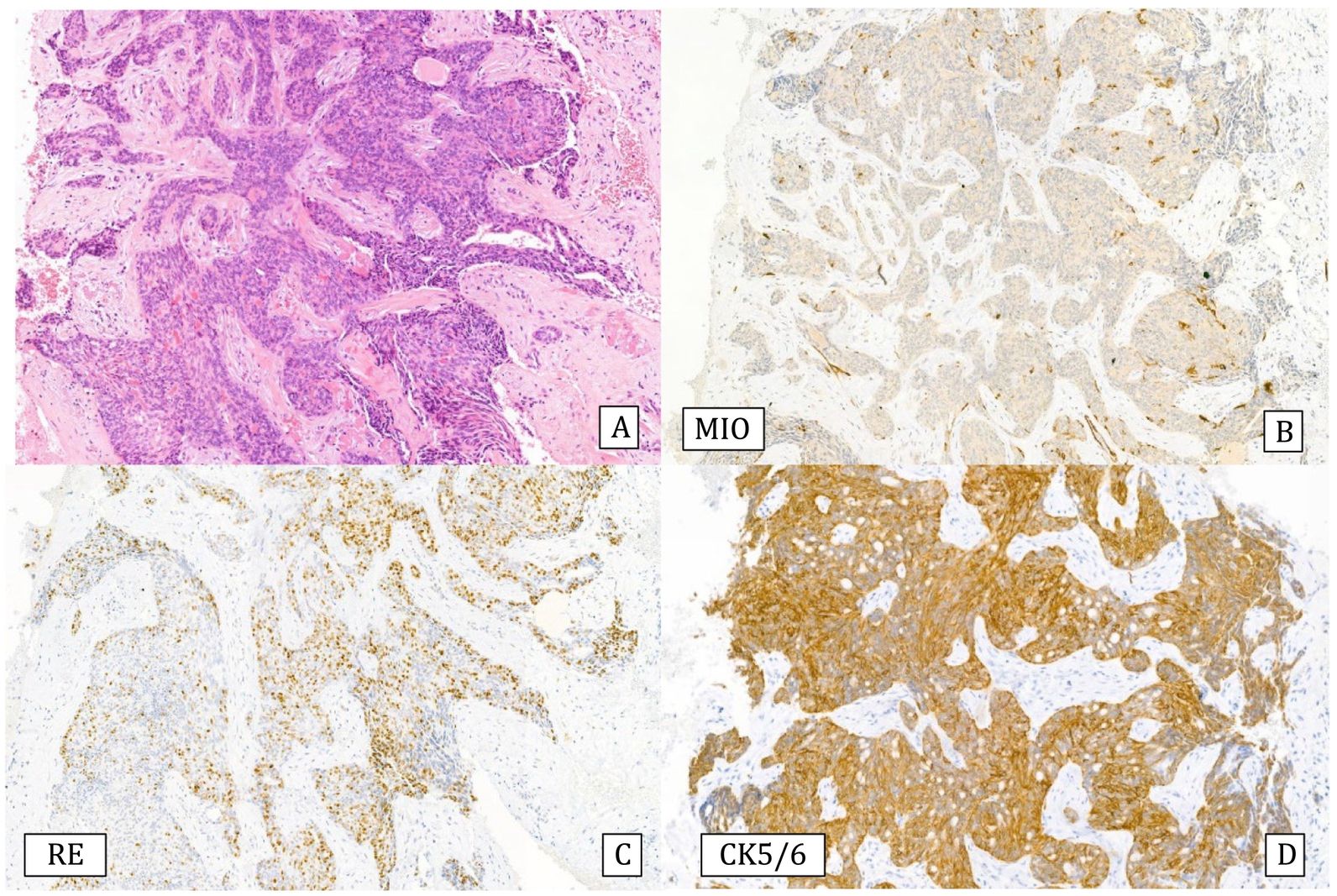

Infiltrating epitheliosis: It is a very rare lesion characterized by infiltrating solid epithelial ducts or nests trapped in a sclerotic-elastotic stroma, containing cells showing UDH pattern. This lesion is not always recognized since some authors include it among the complex sclerosing lesions. The immunohistochemical study, like UDH, shows heterogeneous positivity for CK5/6 and ER can be negative or heterogeneous.50 Myoepithelial staining may be negative or show a discontinuous pattern11 (Fig.7). Genetically, somatic mutations have been observed in the PI3K pathway suggesting that this is a neoplastic lesion.52 It has been proposed that this lesion be classified as a risk lesion, but the number of reported cases is insufficient to describe its behavior.

Spindle cell lesions without atypia or mild atypia: A large group of entities, most of which require surgical excision for correct typing.53 It includes neoplastic lesions such as myofibroblastoma, myxoid lesions, leiomyoma, neurofibroma, spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, fibromatosis, vascular lesions and a group of pseudotumoral lesions, such as the fascicular variant of pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, nodular fasciitis and reactive spindle cell nodule.

Myofibroblastoma is a characteristically nodular, well-demarcated lesion consisting of a proliferation of spindle cells. It shows expression for ER, CD34 and desmin and is negative for cytokeratin.54 The main differential diagnosis is with ILC, especially the epithelioid variant, and with mucinous lesions, the myxoid variant.

Nodular mucinosis is a benign lesion that usually presents in young women in the subareolar region.41 It is a poorly demarcated, slow-growing lesion characterized by myxoid tissue with scattered spindle cells with myofibroblastic features that are positive for vimentin, calponin, smooth muscle actin and negative for cytokeratins and S100 protein.

Myxoma: It is a benign mesenchymal tumor, which is very rare in breast tissue. It may be sporadic or it may present in the context of the Carney complex. Although benign, it may recur in cases of incomplete excision. Histologically, it shows a well-demarcated, myxoid, hypocellular lesion with very few spindle cells.41

Vascular lesions, both benign and malignant, affecting the breast parenchyma can be difficult to distinguish in CNB. The clinicopathological correlation in these patients is very important. Lesions of less than 2 cm are considered to be mostly benign, thus, it would not be necessary to remove them if atypia is not observed. In case of doubt, excision is recommended.55,56

Take home messages- •

Breast lesions classified as B3 include a heterogeneous group of entities.

- •

The role of the pathologist is important in diagnostic accuracy and in the identification of atypical lesions.

- •

The risk of malignancy is higher or lower based on the type of pathology, the presence or absence of associated atypia and the size of the biopsy.

- •

In the presence of combined lesions, atypical ductal hyperplasia prevails when managing the patient.

- •

Radio-pathological correlation in the multidisciplinary committee is very important in order to make a correct diagnosis and give the most appropriate treatment.

- •

Currently, in many of these lesions the treatment can be excision by VAB. In cases with atypical ductal hyperplasia, surgical excision is recommended.

No funding has been used for this review.

Ethical committeeThe characteristics of the review exempt it from ethics committee approval.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.