Historically, pathological and laboratory factors are considered in the prognosis of breast cancer. Tumor resection surgery constitutes the main treatment, but paradoxically, the surgical manipulation and perioperative immunosuppression may predispose to cancer dissemination. Locoregional anesthetic techniques would avoid this immunosuppression, thus improving the oncologic outcomes of surgery. This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic influence of locoregional anesthesia on breast cancer dissemination and recurrence after surgery.

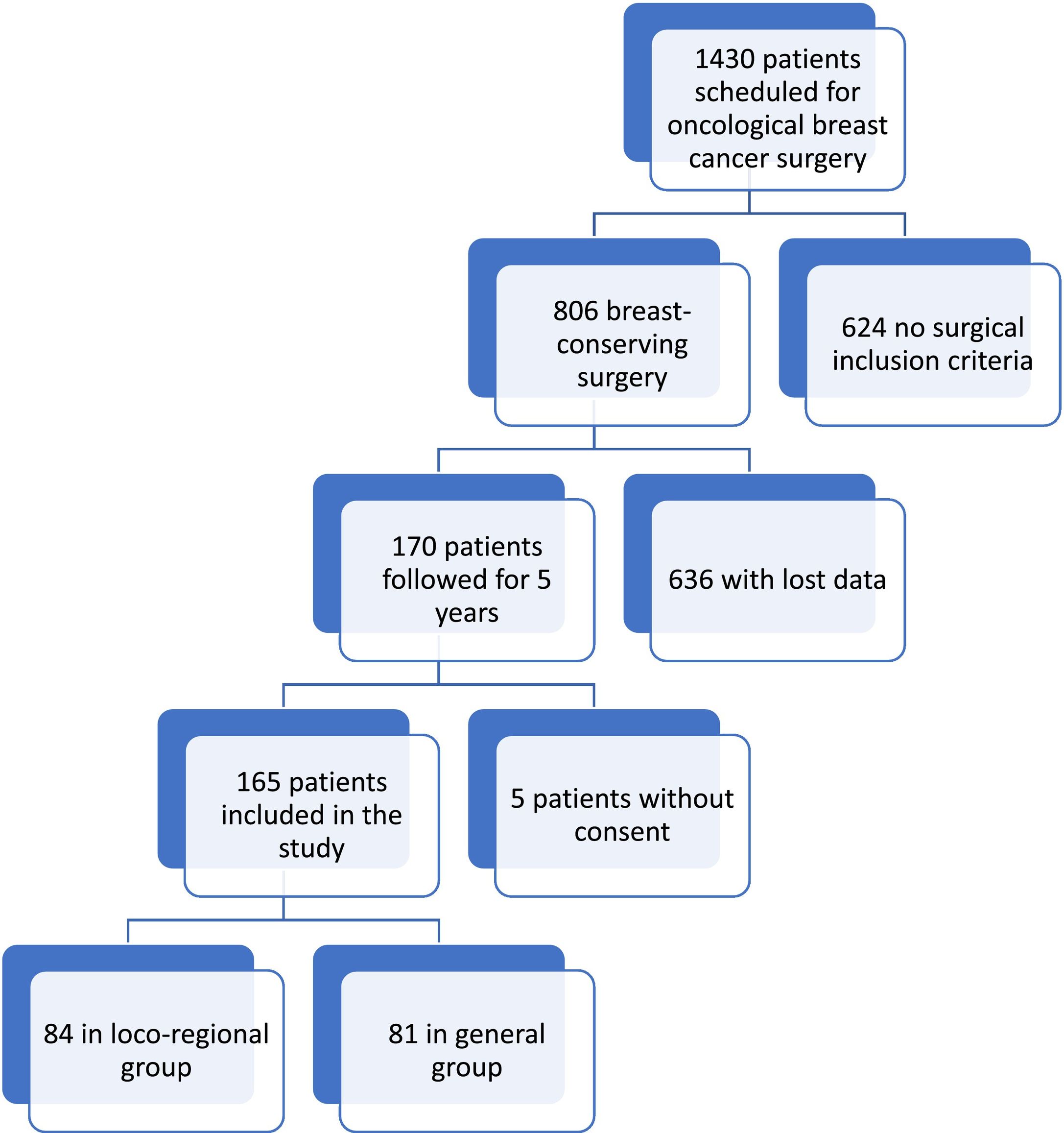

MethodsA retrospective cohort study was performed on 165 centrolobulillar breast cancer patients, scheduled for non-reconstructive breast oncologic surgery between 2012 and 2015. These patients were treated with conservative surgery under general anesthesia (control group, n = 81) or combined anesthesia with a locoregional block (n = 84). Data were collected on age, tumor type (size, stage, lymph node infiltration), immunohistochemical factors (hormone receptors), procedure (duration, technique), anesthesia (general anesthesia or associated with regional blockade), complications, survival, and recurrence.

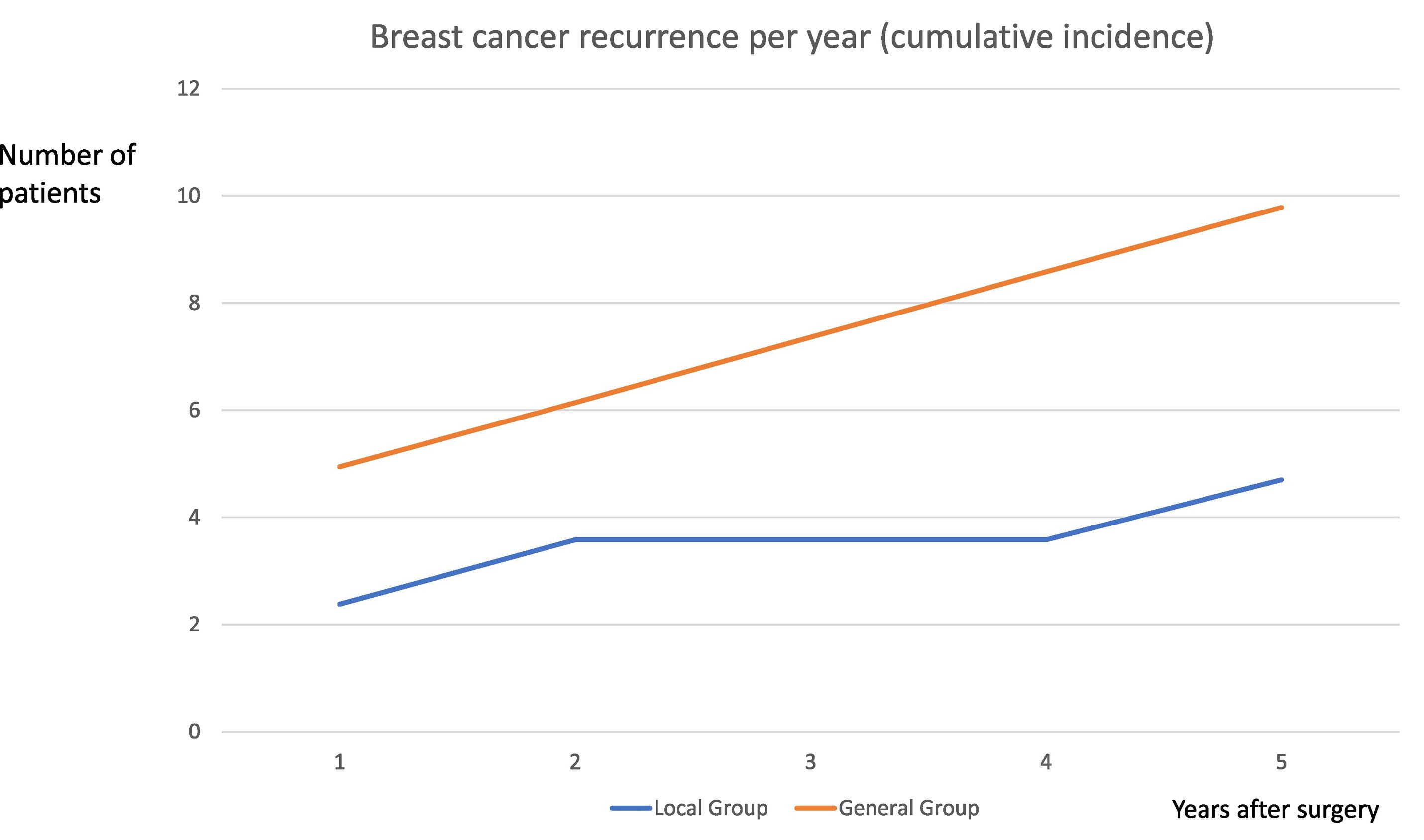

ResultsStatistical analysis demonstrated no significative differences in age, weight, sex, ASA status, and surgical technique and duration. Tumor recurrence was recorded in 6 patients (4 in the general group and 2 in the locoregional group) 1 year after surgery, and 6 (4 in the general group and 2 in the locoregional group) 5 years after. No significant differences between groups in morbi-mortality were found.

ConclusionsFollowing the interfascial analgesic technique, a lower rate of tumor recurrence was observed, but no significant differences.

Históricamente, se han considerado los factores patológicos y de laboratorio para pronosticar el cáncer de mama. La cirugía de resección tumoral constituye el tratamiento principal pero, paradójicamente, la manipulación quirúrgica y la inmunosupresión perioperatoria pueden predisponer a la diseminación del cáncer. Las técnicas anestésicas locorregionales evitarían esta inmunosupresión, mejorando por tanto los resultados oncológicos de la cirugía. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la influencia pronóstica de la anestesia locorregional en la diseminación y recidiva del cáncer de mama tras la cirugía.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de cohorte retrospectivo de 165 pacientes de cáncer de mama centrolobulillar, programadas para cirugía oncológica de mama no reconstructiva entre 2012 y 2015. Dichas pacientes fueron tratadas con cirugía conservadora bajo anestesia general (grupo control, n = 81) o anestesia combinada con bloqueo locorregional (n = 84). Se recopilaron datos sobre edad, tipo de tumor (tamaño, estado, infiltración ganglionar), factores inmunohistoquímicos (receptores hormonales), procedimiento (duración, técnica), anestesia (anestesia general o anestesia asociada a bloqueo regional), complicaciones, supervivencia y recidiva.

ResultadosEl análisis estadístico no mostró diferencias significativas en cuando a edad, peso, sexo, estatus ASA, técnica quirúrgica y duración. Se registró la recidiva tumoral en 6 pacientes (4 en el grupo general y 2 en el grupo locorregional) transcurrido un año de la cirugía, y 6 pacientes (4 en el grupo general y 2 en el grupo locorregional) transcurridos cinco años. No se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los grupos en términos de morbi-mortalidad.

ConclusionesTras la técnica analgésica interfascial, se observó una tasa de recidiva tumoral inferior, aunque sin diferencias significativas.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of death in the female population. Its incidence is increasing by 1–2% annually, due to the aging of the population and the spread of early detection strategies. The mortality rate is 28.2 per 100 000.1

Early surgical resection is the main treatment for breast cancer, and together with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy constitute the therapeutic pillars, following multidisciplinary and individualized protocols of the breast oncology units. The perioperative period is decisive in oncological results after breast surgery, because numerous factors are involved in immune function, angiogenesis, and tumor spread.2 Despite the increasingly individualized and conservative anesthetic–surgical and therapeutic advances, recurrences continue to appear in a high percentage of cases and a survival rate of between 27% and 99% at 5 years.3

Anesthetic–analgesic management and information technology have undergone spectacular changes that favor rapid recovery.4,5 In the perioperative period, anesthesiologists have the possibility of modifying the stress response on the immune system and minimizing residual oncologic disease.6,7

Several potentially immunoprotective measures have been proposed with still limited evidence. These include: minimizing the stress response, premedication, active normothermia, regional anesthesia–analgesia, propofol,8 minimizing the dose of opioids and inhalational anesthetics, anemia prevention, and transfusion sparing, tramadol, NSAIDs, β-blockers and statins, neoadjuvant, and minimally invasive surgical techniques.9 There is no scientific evidence to support one immunoprotective anesthetic plan over another and there is great variability in clinical practice. Different ultrasound-guided interfascial blocks have been described that could eventually displace central regional techniques as they are safer, easier to perform, and with similar effectiveness.10,11

Locoregional anesthesia and propofol-based anesthesia have been shown to reduce surgical stress, perioperative immunosuppression (inhibition of IL-1 and IL-6, VEGF and TGF-β release), angiogenesis, and perioperative inflammation. In addition, it decreases the consumption of volatile anesthetics and opioids, potentially immuno-suppressive.12

The principal objective of this study was to evaluate interfascial analgesic blockade efficacy in the prevention of tumor recurrence and dissemination after breast oncologic surgery, and secondary, to quantify tumor recurrences in patients operated on for hormone receptor (ER and PR) positive breast cancer under combined anesthesia of interfascial analgesic chest wall blockade (Brilma, PEC, and/or BRCA) and opioid-free general anesthesia, annually, up to 5 years post-operatively and comparison between the general group (general anesthesia only) and group locoregional (combined general anesthesia and locoregional block) in terms of mortality and recurrences in both breasts.

Materials and methodsRetrospective, observational cohort study. Approved by the local Ethics Committee in Academic Clinic Hospital in Valladolid with code PI 17-328 in patients undergoing scheduled breast oncologic oncology surgery, from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2015.

Inclusion criteria: Age between 18 and 80 years, ASA I-III, body mass index <25, tumor stage I–II (T1-2N0-1M0), intervened by breast oncology surgery between January 2, 2012 and December 20, 2015, tumor size less than 5 cm, hormone receptors (ER, PR, and HER) positive. Informed consent for entry into the study (according to the standardized model by the CEIC of the Hospital).

Exclusion criteria: Loss of patient data (due to referral to another center), bilateral cancer, reconstructive breast surgery, history of other primary tumors, carcinoma in situ, male sex, not meeting inclusion criteria, and neoadjuvant therapies.

Procedure: The anesthetic technique was the usual one for this type of surgery: After venous cannulation and basic monitoring, an anesthetic block was performed before induction of general anesthesia in the locoregional group.

The study patients were grouped according to whether they had received general anesthesia (group G) or combined anesthesia (group L) associating general anesthesia and interfascial wall block (serratus-intercostal block, pectoral block, or pecto-intercostal block or block of the anterior branches of intercostal nerves). The blocks were performed on the awake patient, in the supine position, with ultrasound (Siemens Acuson P300), high-frequency linear transducer 6–15 MHz, and Stimuplex® 22G 100 mm needle (Braun medical), as shown in Fig. 1.

The serratus-intercostal block was performed by placing a linear transducer in the mid-axillary line of the breast to be blocked, introducing the needle through the lower edge of the probe in a caudal to cranial direction, advancing carefully while keeping the tip of the needle in view until it is positioned between the serratus anterior muscle and the external intercostal muscle. Once there, the anesthetic was deposited, without losing sight of the diffusion of the anesthetic within the area to be blocked. After the correct placement of the needle tip and after negative aspiration through the needle, 2 ml of local anesthetic was administered to confirm the correct placement of the needle tip, and subsequently, a total of 20 ml of bupivacaine 0.25% was administered.

Sometimes, it was necessary to complement the blockade with a pecto-intercostal block. The needle was introduced in a craniocaudal direction in the plane with the probe in the anterior parasternal line, to reach the plane between pectoral and intercostal muscles. After confirming the correct position of the needle and a negative aspiration, 10 ml of bupivacaine 0.25% was administered.

In the control group (G), only general anesthesia was administered according to standard protocol. In both groups, all patients received intravenous general anesthesia by TCI (Target-Controlled Infusion Pump) with propofol in Schnider mode at 2–5 μg/ml. If an increase in basal heart rate or mean arterial pressure of more than 30% over basal values was observed, 100 μg of fentanyl was administered. After induction, an appropriately sized laryngeal mask was inserted. In 10 cases, the administration of rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) was necessary to facilitate the insertion of the laryngeal mask. When rocuronium was administered, intravenous sugammadex 0.5 mg was used before the removal of the supraglottic device. In all cases, intravenous dexamethasone was administered intravenously at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg, paracetamol 1 g, and dexketoprofen 50 mg.

After the surgery and once consciousness and reflexes were recovered, each patient was admitted to the Post Anesthesia Recovery Unit (URPA). If analgesic rescue was required, metamizole 2 g or morphine chloride 1 mg intravenously was administered, repeating doses if necessary every 5 min. The patient was discharged to the Hospitalization Unit when the patient reported no pain (Numeric Scale less than 3/10), no nausea, or other surgical complications. In case of pain, she was treated with 2 mg morphic chloride boluses every 5 min until VAS <3/10 was achieved.

VariablesWe collected the following data from the history: age, weight, height, ASA physical status, date of intervention, time of duration, surgical technique (conservative surgery or mastectomy), opioid use (dose and number of boluses), transfusion use, tumor size, estrogen receptor-positive or negative, progesterone receptor-positive or negative, human epidermal growth factor (HER-2), Ki-67 expression, and whether chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy was used. The principal objective of this study was to evaluate interfascial analgesic blockade efficacy in the prevention of tumor recurrence and dissemination after breast oncologic surgery, and secondary, to quantify tumor recurrences in patients operated for hormone receptor (ER and PR) positive breast cancer under combined anesthesia of interfascial analgesic chest wall blockade (serratus-intercostal block, pectoralis, and/or pecto-intercostal block) and opioid-sparing general anesthesia, annually, up to 5 years post-operatively and comparison between the general group (general anesthesia only) and group locoregional (combined general anesthesia and locoregional block) in terms of mortality and recurrences in both breasts.

+ Data of affiliation and background.

++Demographic data: age, sex, weight, and height.

++Evaluation of physical condition with the ASA scale. Comorbidities.

++ Personal information: address and telephone number.

++ Toxic habits, history of drug abuse.

++ Anesthetic–surgical treatment.

++ Diagnosis motivating the surgical intervention.

++ Surgical technique performed. Duration of surgery.

++ Bleeding requiring transfusion. Other intraoperative complications.

++ Inpatient surgery or major outpatient surgery circuit.

++ Anesthetic procedure: techniques and drugs used. Group G (general) or L (associated general and locoregional).

++ Degree of difficulty of the anesthetic-surgical technique. Each surgical team member (2 nurses, 2 surgeons, and 1 anesthesiologist) evaluated their technique using a categorical scale between 0 and 5, where 0 was no difficulty and 5 was the maximum. The mean of the 5 scores was recorded.

++ Oncological information.

++ Adjuvant treatments: chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy.

++ TNM stage, tumor size, estrogen receptor-positive or negative, progesterone receptor-positive or negative, human epidermal growth factor (HER-2), Ki-67 expression.

+ Post-operative period.

++ Analgesic treatment performed.

++ Need for reoperation. Whether resection margins were clear of tumor or not by analyzing anatomopathological results.

++ Post-operative complications during the hospital stay or at home (for major outpatient surgery patients): respiratory, cardiac, renal, hepatic, hematologic, neurologic, and/or infectious.

++ Length of hospital stay.

++During annual follow-up.

++Survival: Yes/No. Survival was defined as the interval between the surgery date and the death date.

++ Recurrence: Yes/No, location, recurrence-free time. The recurrence-free survival is defined as the interval between the date of intervention and the date of breast cancer recurrence or death. Breast cancer recurrence was classified as locoregional or systemic, and confirmed by radiological or anatomopathological examination. It was recorded local tumor relapse, regional relapse (i.e., in the axilla, supraclavicular fossa, and internal mammary chain), distant relapse, disease-free survival, and overall survival.

++ Admission.

Data collectionData was collected from the electronic medical records of the patients who have signed the informed consent to enter the study. The variables were entered into a database developed for this study with the corresponding security protocols according to regulations.

An external investigator reviewed the medical records to check for mortality or possible recurrence consultation 1 year after the intervention (the last call was made on December 30, 2022).

Data analysisFirstly, a descriptive study of the variables studied was carried out. To define quantitative variables, percentages, and numbers were used, and categorical variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation or median for continuous variables. A bi-variate analysis was performed to compare the groups under study (General vs inter-fascial). If the contrast variable was continuous in nature, the Student's t-test for unrelated data was applied. On the other hand, if the contrast variable was categorical, the statistical inference was performed using the Chi-square test. Values with P<.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed with the PASW®v17.0 statistical package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsFrom January 2, 2012 to December 31, 2015, 1430 patients were operated for breast cancer in our institution, 806 of whom met the criteria for inclusion in the study. Follow-up at 5 years after the intervention was recorded in only 170 patients. Five patients withdrew consent for the use of their data and were excluded from analyses, leaving 165 participants (Fig. 1).

During the study period, 165 patients underwent surgery and met the study criteria: 84 of them were operated under combined anesthesia (general anesthesia associated with interfascial block) (L group) and 81 under general anesthesia (G group). Both groups had comparable characteristics in terms of body mass index, physical condition according to the ASA scale, duration of surgery, and equivalence of perioperative opioid doses (fentanyl, remifentanil, or morphine chloride) (Table 1) (See Table 2).

Characteristics of patients. The results are expressed as mean (standard deviation). ASD = Absolute standard difference. ASA American Society of Anaesthesiologists. L group: interfascial block associated with general anesthesia. G group: General Anesthesia. Variables with ASD ≥0,085 were considered to be unbalanced.

| Locoregional (L) Group | General (G) Group | ASD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 (14) | 35 (18) | 0.07 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.21 |

| ASA physical status | 0.07 | ||

| ASA I | 22 | 20 | |

| ASA II | 42 | 40 | |

| ASA III | 20 | 21 | |

| Surgery duration (minutes) | 63 (24) | 65 (30) | 0.04 |

| Fentanyl (μg) | 100 (140) | 120 (200) | 0.09 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 100 (0–200) | 90 (10–110) | 0.12 |

| Allogeneic blood (mL) | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

Tumor characteristics. All of the patients in the study presented estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, human epidermal growth factor (HER-2), and Ki-67 expression positives. The results are expressed as the number of subjects (percentage).

| L Group | G Group | ADS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor site | 0.040 | ||

| Left | 44 | 41 | |

| Right | 40 | 40 | |

| Tumor findings | |||

| Microcalcification | 27 (33%) | 24 (29.62%) | 0.041 |

| Parenchymal distortion | 8 (9.52%) | 11 (13.58%) | 0.034 |

| Mass | 65 (77.38%) | 62 (76.54%) | 0.004 |

| Other | 4 (4.94%) | 5 (6.17%) | 0.027 |

| Estrogen receptor | 84 (100%) | 81 (100-%) | 0.030 |

| Resection margins (mm)a | 5 (2–10) | 5 (2–10) | <0.001 |

| Pathology stage, tumor | 0.054 | ||

| Tx | 0 | 0 | |

| T0 | 1 (1.20%) | 1 (1.12%) | |

| T1 | 48 (57.14%) | 49 (60.49%) | |

| T2 | 30 (35.71%) | 28 (34.57%) | |

| T3 | 5 (5.95%) | 3 (3.70%) | |

| T4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pathology stage, nodes | 0.007 | ||

| NX | 1 (1.20%) | 1 (1.20%) | |

| N0 | 50 (59.52%) | 48 (59.26%) | |

| N1 | 20 (23.81%) | 21 (25.93%) | |

| N2 | 81 (8%) 81 (8%) | ||

| N3 | 98 (9%) 101 (10%) | ||

| Pathology stage, Metastasis M0 | 84 (100%) | 81 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Tumor TNM stage | 0.057 | ||

| 0 | 2 (2.40%) | 2 (2.40%) | |

| 1 | 40 (47.62%) | 40 (49.38%) | |

| 2 | 30 (35.71%) | 38 (46.91%) | |

| 3 | 12 (14.29%) | 1 (1.20%) | |

| Nottingham Prognostic Index | 4.1 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.2) | 0.015 |

Clinical and demographics characteristics, tumor grade and stage, and surgical management variables were well-balanced between study groups (Table 1), except for age index (ASD 0.09), intraoperative fentanyl (ASD 0.09), and estimated blood loss (ASD 0.12). The general group was older, required higher doses of fentanyl, and had a higher estimated range of blood loss than the locoregional group.

Among the comorbidities, we registered 1 case of addiction to cocaine, 1 case of epilepsy, 2 cases of cerebrovascular disease, and 1 case of leukopenia, all of them in the general group.

All patients studied had unilateral centro-lobular cancer located in outer quadrants (97): upper and tail of the breast (67 patients); inner quadrants (60): upper (32), and lower (28); and periareolar (8). In 90 patients, they were located in the left breast (54.5%) and 75 in the right breast (45.5%).

The surgical technique used was nodulectomy in 85 patients (56 in the locoregional group and 29 in the general group), mastectomy in 70 cases (21 in the locoregional group and 29 in the general group), and axillary lymphadenectomy in 10 cases (7 in the locoregional group and 3 in general group). Selective sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed by radionuclide labeling in 85 patients (51.51%). The biopsy result was negative for micrometastasis in 73 patients (67 in the locoregional group and 6 in the general group) and positive in 12 cases (8 in the locoregional group and 4 in the general group).

One year after surgery, 10 recurrences were recorded (6 in the general group and 4 in the locoregional group) and another 10, 5 years after (see Fig. 2). No mortality was registered. Most of them when regional recurrence, in axilla lymphatic nodes (7 cases, 4 in the general group in the third year and 3 in the locoregional group in the second and fourth year after surgery).

Other complications registered were the following: 40 patients with chronic pain, 15 of them prevented daily activity, and other complications in 16 patients: hematoma in 9 patients (5 in the locoregional group and 4 in the general group), surgical wound infection in 2 patients (all in locoregional group), seroma in 2 patients (1 in locoregional group and 1 in general group), paresthesia in arm in 2 patients (all in general group), none attributable to the anesthetic technique. One case of pneumothorax was recorded in the general group.

The presence of post-operative vomiting or nausea requiring treatment was registered in 10 cases (6 in the general group and 4 in the locoregional group).

In the comparison between groups, we found no significant differences in the incidence or intensity of chronic pain, nor the complications between the locoregional and general groups, although, in the locoregional group, the age of the patients was significantly lower.

DiscussionDespite current technological and therapeutic advances, breast cancer is the most frequent tumor in the female sex, the second cause of mortality, and its incidence increases with age.13 Effective therapy for breast cancer requires maximum therapeutic efficacy, with minimal undesirable effects to ensure a good quality of life for patients.14

The incidence of breast cancer recurrences in the studied population is similar to that found in the literature.13 Of the 36 924 women with breast cancer in the Pedersen et al study,15 20 315 survived 10 years without disease, and 2595 of these developed late recurrence (incidence rate of 15.53 per 1000 person-years), between years 10 and up to 32 after primary diagnosis. In other studies, tumor size greater than 20 mm, lymph node-positive disease, and estrogen receptor-positive tumors were associated with increased cumulative incidences and risks of late recurrences.

Life expectancy in most of the anatomopathological types of gynecological cancer is high, as evidenced by Lyngholm et al,16 with incidences of local recurrence and disease-specific mortality of 15.3% and 25.8%, respectively after 20 years. And cumulative incidences at 20 years were 18.9%, 10.5%, and 12.4% of local recurrences, and disease-specific mortality of 28.9%, 18.9%, and 28.4% in young (≤45 years), middle-aged (46–55 years), and older (≥56 years) women, respectively. Although the 2 groups of patients in our study were comparable, the age of the patients in the general group was lower, which could favor recurrence.16

Given the long life expectancy of breast cancer, it is important to improve the quality of life of these patients. Among the prognostic factors are the degree of an extension, histological type, and hormone receptors. Preventive measures for the development of breast cancer, lifestyle, and early diagnosis measures have been described; but once the disease has been established, only an exquisite treatment is possible and total surgical resection of the tumor mass remains the main therapeutic pillar.14

Tumor latency is a phase of cancer development in which tumor cells are present, but the cancer does not progress. It includes the concept of cellular latency, which indicates the reversible passage of a cancer cell to a quiescent state, and tumor mass latency, which indicates the presence of neoplastic masses that have reached cell population equilibrium through balanced rates of growth/apoptosis. The mechanisms by which tumors remain dormant and what triggers their reactivation are fundamental questions in cancer biology and are highly dynamic in space and time. Understanding the mechanisms of cellular and tumor latency has provided the foundation for addressing this otherwise stable period of cancer development to prevent recurrence and maximize therapeutic benefits.17

The surgery itself and anesthesia can contribute to the spread of cancer, so knowing the measures to be adopted is essential for the exquisite treatment of these patients since they are measures in which we can act actively. Surgery depresses cell-mediated immunity, reduces concentrations of tumor-related anti-angiogenic factors (e.g., angiostatin and endostatin), increases concentrations of pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor, and releases growth factors promoting malignant tissue's local and distant growth.18 Volatile anesthetics (sevoflurane) impair many immune functions (e.g., natural killer cells) and directly facilitate cancer cell growth.19 The results of retrospective comparisons between regional and volatile anesthetic approaches have been variable.20 Yet, cohort data suggest that an intravenous anesthetic might be preferable to volatile anesthetics.21

The putative relation between regional analgesia and cancer recurrence is based on narrative review, mechanistic and animal evidence, along with observational analyses.22

The analgesic technique occupies a primordial role since pain is directly related to pain, and many anesthetics can facilitate angiogenesis and immunosuppression. At an experimental level, it has been demonstrated that the analgesic treatments most commonly used in the therapy of severe chronic oncological pain (opioids) constitute an independent risk factor in the recurrence and metastasis of breast cancer.10 Opioid analgesics inhibit both cellular and humoral immune function in humans, increase angiogenesis, and promote breast tumor growth in rodents.23 Avoiding the occurrence of pain using the anesthetic blockades studied, together with an opioid-free anesthetic technique, could improve the prognosis of these patients, but there is limited research on this subject area.24

Several studies relate recurrences after cancer surgery to 3 perioperative factors that alter the defenses against cancer: the response to surgical stress and the use of opioids for analgesia. All of these are reduced by regional anesthesia–analgesia anesthesia. The study by Sessler et al,25 a multicentric essay in 2132 women, compared breast cancer recurrence after potentially curative surgery as lower with regional anesthesia with paravertebral blocks and the anesthetic propofol than with general anesthesia with volatile anesthetics sevoflurane and opioid analgesia, and in the reduction of persistent incisional pain. They concluded that paravertebral blocks and propofol sedation do not reduce breast cancer recurrence. Further trials are needed to evaluate the potential benefits of regional analgesia in patients undergoing larger operations, more surgical stress, more pain, and require more opioid analgesia.

LimitationsSingle-center study with a small sample size. This model constitutes the first phase of a multicenter study at the national level, in collaboration with working groups that are investigating both tumor recurrence and the long-term implications of anesthetic and analgesic techniques (infections, chronification of acute post-operative pain, etc.). Multiple variables or confounding factors are involved in tumor dissemination and it is difficult to homogenize all of them. Recurrences of intraductal breast cancer can appear up to 39 years after diagnosis,16 and many patients in the study will not be included in this period. Patients in the interfascial group received fewer opioids (with potential immunosuppressive effect) than those in the overall group, which was not considered. Other comorbidities, whose decompensation could have caused the death of the patient, have not been considered.

ConclusionsFollowing the interfascial analgesic technique, a lower rate of tumor recurrence is observed. Despite the encouraging in vitro studies on locoregional and opioid-free anesthesia on breast cancer prognosis, the anatomopathological complexity and the numerous confounding factors do not allow in vivo conclusions to be drawn.

FundingThis work has not received any funding.

Ethical responsibilitiesInstitutional Review Board Statement: Approved by the local Ethics Committee in Academic Clinic Hospital in Valladolid with code PI 17-328.

Informed consent statementThe informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.