Immediate Life Support training is under-represented in medical degrees and little information is available on the medium-term effectiveness of its teaching. Our aim was to analyse the forgetting curve in medical students who received specific training in the three main procedural competencies of Immediate Life Support.

Material and methodsA prospective 3-month longitudinal study was conducted on final year medical students at a Spanish university. The items assessed were grouped into three competencies: the performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (nine items), instrumentalised airway management with a supraglottic device (five items) and the identification of basic arrhythmias responsible for cardiorespiratory arrest (four items). All measurements were assessed immediately after the training programme and at three months. McNemar's tests were used for statistical analyses.

ResultsThe medical students recruited showed high rates of correct execution of the manoeuvres for all assessed items, both immediately after the programme and at three months. Over 90% of students performed all the manoeuvres correctly at three months, except for appropriate cardiac massage frequency (85.71%). No significant differences were appreciated between the two assessments.

ConclusionThe 3-month forgetting curve in Immediate Life Support was non-existent for medical students, suggesting that these programmes are effective in the medium term. This study provides further evidence on a discipline that is undertrained in medical degrees and that is scarcely studied in the current literature.

La formación en Soporte Vital Inmediato está poco representada en las titulaciones de medicina y se dispone de poca información sobre la eficacia a medio plazo de su enseñanza. Nuestro objetivo fue analizar la curva de olvido en los estudiantes de medicina que recibieron formación específica en las tres principales competencias procedimentales del Soporte Vital Inmediato.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio longitudinal prospectivo de 3 meses en estudiantes de último curso de medicina de una universidad española. Los ítems evaluados se agruparon en tres competencias: la realización de la reanimación cardiopulmonar (nueve ítems), el manejo instrumentalizado de la vía aérea con dispositivo supraglótico (cinco ítems) y la identificación de las arritmias básicas responsables de la parada cardiorrespiratoria (cuatro ítems). Todas las mediciones se evaluaron inmediatamente después del programa de formación y a los tres meses. Se utilizó el test de McNemar para los análisis estadísticos.

ResultadosLos estudiantes de medicina reclutados mostraron altas tasas de ejecución correcta de las maniobras para todos los ítems evaluados, tanto inmediatamente después del programa como a los tres meses. Más del 90% de los estudiantes realizaron correctamente todas las maniobras a los tres meses, excepto la frecuencia de masaje cardíaco adecuada (85,71%). No se apreciaron diferencias significativas entre las dos evaluaciones.

ConclusiónLa curva de olvido a los tres meses en Soporte Vital Inmediato fue inexistente para los estudiantes de medicina, lo que sugiere que estos programas son eficaces a medio plazo. Este estudio aporta más evidencias sobre una disciplina poco formada en las carreras de medicina y escasamente estudiada en la literatura actual.

It is estimated that cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA) has a prevalence of 35–55 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year in industrialised countries.1 The efficacy of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the treatment of these events is directly proportional to the training received and inversely proportional to the time elapsed between the occurrence of CRA and the initiation of the manoeuvres.2 In this regard, training in Immediate Life Support (ILS) is essential, since it teaches trainees to quickly recognise early signs of CRA and activate the ABCDE sequence, within the Advanced Life Support (ALS) competencies. Undergraduate ILS courses have been shown to reinforce CPR skills before the beginning of the MIR (medical intern training programme for physicians in Spain) in the final (sixth) year of the medical degree.3 To date, only three studies evaluating ILS training for medical students have been reported.3–5

It is essential for trainees to minimise the forgetting curve to maintain cognitive and procedural skills over time. Different hypotheses have been proposed regarding the estimated retraining time depending on the training modality received.6–10 However, most of these evaluations have been performed on basic life support (BLS) and/or ALS training programmes.

The aim of this study was to analyse the 3-month forgetting curve in medical students who received specific training in the three main procedural competencies included in ILS.

Material and methodsA prospective observational study was conducted in sixth-year students of the Degree of Medicine of a Spanish university enrolled in the ALS elective course from January to April 2018. All participants were appropriately informed through detailed explanation and completion of informed consent. The Research Ethics Committee of a Spanish university issued a favourable report on the program submitted under number 1686/CEIH/2020.

The ILS training course consisted of workshops covering the performing of quality CPR, instrumentalised airway management with a second-generation supraglottic device (IAMSGD) and identification of the basic arrhythmias responsible for CRA. These skills followed a conceptual model based on the 2015 recommendations of the European Resuscitation Council.11 The assessment of the results of these workshops was performed immediately after completion of the course, and after three months. These assessments were performed by professionals with a standardised level of training, all of whom were ALS and/or BLS instructors and not directly involved in the present study.

The manoeuvres were performed using simulation instruments such as the Resusci Anne Simulator® (Laerdal®, Stavanger, Norway), the TrueCPR® CPR quality control device (Physiocontrol, Redmond, USA), the GE Healthcare® Responder 3000 manual defibrillation device (General Electric, New York, USA), the GE Healthcare® Responder 3000 manual defibrillation device (General Electric, New York, USA), the HeartSim® 200 arrhythmia simulator (Laerdal®, Stavanger, Norway), a comprehensive SimPad Plus® CPR quality simulator (Laerdal, Stavanger, Norway), advanced simulators for airway instrumentation (Laerdal, Stavanger, Norway) and a third-generation Bryden and Byden Pro® SV simulator (Innosonian, Carlstadt, New Jersey, USA).

The 18 items (manoeuvres) assessed were grouped intothree competency areas (CPR, IAMSGD and identification of arrythmias). The items were assessed as correct or incorrect for each participant.

Dichotomous qualitative variables were analysed with SPSS version 15© (IBM - Armonk, New York, USA). After obtaining the respective contingency tables, McNemar's tests were performed for the comparison of paired qualitative variables (immediately after the course and after three months). The tests were two-sided with a 0.05 level of acceptance.

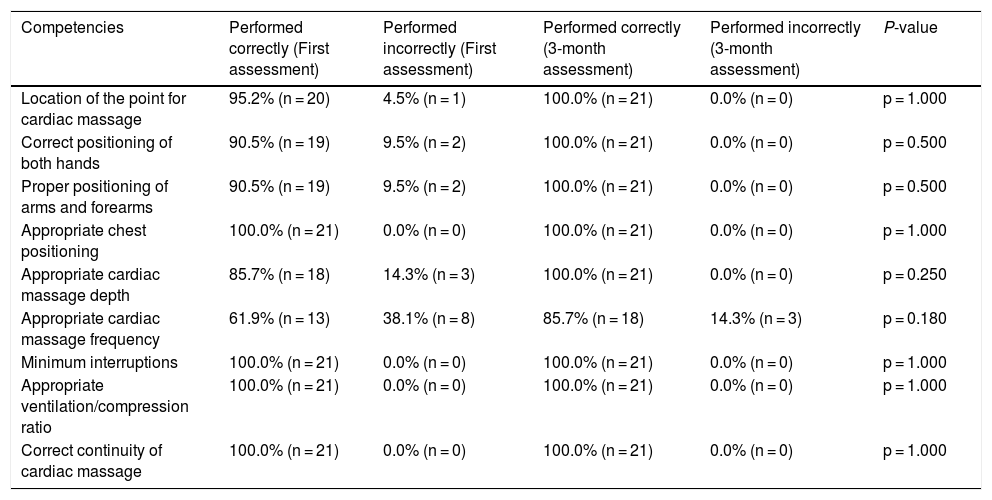

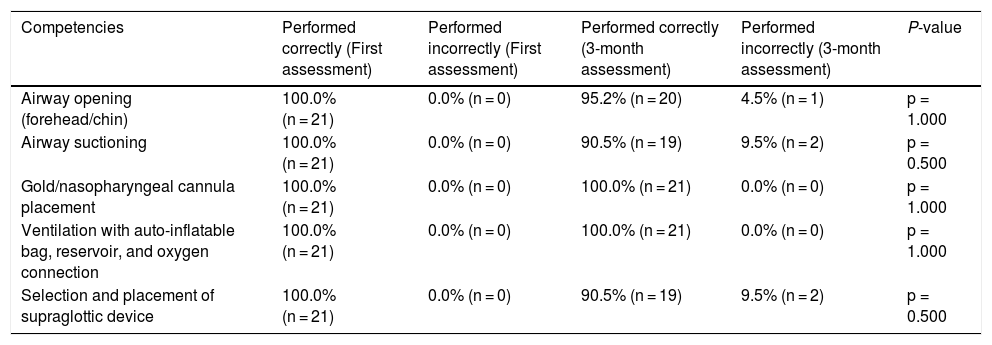

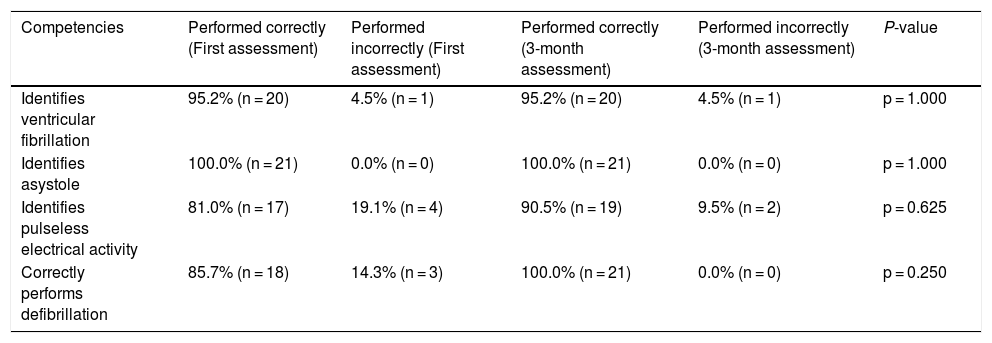

ResultsA total of 21 participants were recruited of which 52.4% (n = 11) were female and 47.6% (n = 10) were male. Tables 1, 2 and 3 show the evaluation of the forgetting curve at three months.

Assessment of quality Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

| Competencies | Performed correctly (First assessment) | Performed incorrectly (First assessment) | Performed correctly (3-month assessment) | Performed incorrectly (3-month assessment) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of the point for cardiac massage | 95.2% (n = 20) | 4.5% (n = 1) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Correct positioning of both hands | 90.5% (n = 19) | 9.5% (n = 2) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 0.500 |

| Proper positioning of arms and forearms | 90.5% (n = 19) | 9.5% (n = 2) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 0.500 |

| Appropriate chest positioning | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Appropriate cardiac massage depth | 85.7% (n = 18) | 14.3% (n = 3) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 0.250 |

| Appropriate cardiac massage frequency | 61.9% (n = 13) | 38.1% (n = 8) | 85.7% (n = 18) | 14.3% (n = 3) | p = 0.180 |

| Minimum interruptions | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Appropriate ventilation/compression ratio | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Correct continuity of cardiac massage | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

Assessment of airway instrumentation with supraglottic device.

| Competencies | Performed correctly (First assessment) | Performed incorrectly (First assessment) | Performed correctly (3-month assessment) | Performed incorrectly (3-month assessment) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway opening (forehead/chin) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 95.2% (n = 20) | 4.5% (n = 1) | p = 1.000 |

| Airway suctioning | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 90.5% (n = 19) | 9.5% (n = 2) | p = 0.500 |

| Gold/nasopharyngeal cannula placement | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Ventilation with auto-inflatable bag, reservoir, and oxygen connection | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Selection and placement of supraglottic device | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 90.5% (n = 19) | 9.5% (n = 2) | p = 0.500 |

Assessment of identification of the basic arrhythmias responsible for cardiorespiratory arrest (CRA).

| Competencies | Performed correctly (First assessment) | Performed incorrectly (First assessment) | Performed correctly (3-month assessment) | Performed incorrectly (3-month assessment) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifies ventricular fibrillation | 95.2% (n = 20) | 4.5% (n = 1) | 95.2% (n = 20) | 4.5% (n = 1) | p = 1.000 |

| Identifies asystole | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 1.000 |

| Identifies pulseless electrical activity | 81.0% (n = 17) | 19.1% (n = 4) | 90.5% (n = 19) | 9.5% (n = 2) | p = 0.625 |

| Correctly performs defibrillation | 85.7% (n = 18) | 14.3% (n = 3) | 100.0% (n = 21) | 0.0% (n = 0) | p = 0.250 |

First, the competencies for performing quality CPR were analysed and compared (Table 1). No differences in the two measurements (immediately after the course and at three months) were found for the items: The location of the point for cardiac massage (p = 1.000), appropriate positioning of the thorax (p = 1.000), minimum possible interruptions during the manoeuvre (p = 1.000), appropriate ventilation/compression ratio (p = 1.000), correct continuity of cardiac massage (p = 1.000), the manoeuvres of correct positioning of both hands (p = 0.500), the correct position of arms and forearms (p = 0.500), the correct depth of the manoeuvre (p = 0.250) and the correct frequency of the CM manoeuvre (p = 0.180). At three months, participants showed rates of 100% of correct performance for all items except for the correct frequency of the CM manoeuvre (85.7%).

Second, IAMSGD was assessed as shown in Table 2. No differences were found for airway opening (p = 1.000), airway suctioning (p = 0.500), nasopharyngeal cannula placement (p = 1.000), ventilation manoeuvres (p = 1.000), and supraglottic device selection and placement (p = 0.500). At three months, participants showed rates of over 90% for correct performance for all items.

Finally, the identification of the basic arrhythmias responsible for CRA is presented in Table 3. No differences were shown for the identification of ventricular fibrillation (p = 1.000), the identification of asystole (p = 1.000), the identification of pulseless electrical activity (p = 0.625) and the performance of defibrillation (p = 0.250). At three months, participants showed rates of over 90% for correct performance for all items, and percentages were even superior to those obtained immediately after the course.

ConclusionWe performed a preliminary evaluation of the 3-month forgetting curve after an Immediate Life Support training programme for medical students. We found no differences in the correct performance of all the manoeuvres when comparing the assessment immediately after the course and the assessment at three months.

The manoeuvres related to quality CPR concerning the location of the appropriate point to begin cardiac massage, the position of hands and arms, and the appropriate depth of compressions showed less practical acquisition in the first assessment but were better remembered in the second test at three months. On the other hand, maintaining an appropriate frequency of compressions was the manoeuvre that scored lowest initially (61.9%) and was not retained by all participants at the second assessment (85.7%). These results contrast with those presented by Del Castillo et al.5. In their study, conducted on students training in paediatric care, the correct performance of the frequency of cardiac compressions was observed but the depth was not optimal. This discrepancy may be due to the difference in the target populations. Regarding the IAMSGD skills, there was a lack of retention in airway suctioning and supraglottic device selection and placement. The study proposed by Nicol et al.3 using the ILS course shows better airway management with a retention of up to six to nine months. Finally, manoeuvres related to the identification of basic arrhythmias responsible for CRA showed higher levels of retention in the second assessment. These results may be due to the impact of these manoeuvres on the immediate reversal of CRA. Interprofessional learning in ILS between medical and nursing students has also demonstrated more successful skill acquisition than the unprofessional model.4

Despite the limited evidence regarding the retention of skills in ILS, the forgetting curve could be compared with those obtained in BLS because of the similarity in some manoeuvres. In the present study, the analysis of the forgetting curve showed a curve with virtually no slope for most skills, or positive slope on some items. Although the re-assessment was at three months, other studies have shown significant differences at six months in the correct performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation manoeuvres in Brazilian medical students.12 It is therefore essential to carry out refresher courses, which might be scheduled every month,13 every two months,14 every six months,15,16 after twelve months6 or up to eighteen to twenty-four months.9 In any case, we showed that, at three months, the practical acquisition of competencies remains.

Among the limitations, we found that simulation on inert models might interfere with the performance of the CPR sequences. However, the participants were medical students who were enrolled in an elective course on ALS. Therefore, it is possible that there is a selection bias due to student motivation which could limit the external validity of the results when applied to the general medical student population. Lastly, the study conducted was a preliminary one-centre study with measurements at the end of the course and at three months. In the future, we would like to broaden this study to other centres and include longer-term measurements of the forgetting curve.

Our study provides evidence that ILS programmes are useful for medical students for at least three months. We provide evidence supporting the implementation of these programmes regularly in medical degrees in Spain. Due to the limited existing evidence, the results summarised may be useful in future studies evaluating skill acquisition in these resuscitation manoeuvres.

The forgetting curve at three months for an Immediate Life Support training programme was non-existent for medical students. Participants showed rates of over 90% of correct performance for most of the manoeuvres analysed. This study provides further evidence on a discipline scarcely studied in the current literature and serves as a starting point for the initiation of studies that include a larger number of subjects, extension to other university centres and longer-term measurements.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of FundingThe authors declare no conflict of interest.