More than 30 years after its discovery, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection remains the most common cause of gastric and duodenal diseases. H. pylori is the leading cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric MALT lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma. Several consensuses have recently been published on the management of H. pylori infection. The general guidelines of the Spanish consensus, the Toronto Consensus and the Maastricht V Consensus of 2016 are similar but concrete recommendations can vary significantly. In addition, the recommendations of some of these consensuses are decidedly complex. This position paper from the Catalan Society of Digestology is an update of evidence-based recommendations on the management and treatment of H. pylori infection. The aim of this document is to review this information in order to make recommendations for routine clinical practice that are simple, specific and easily applied to our setting.

Más de 30 años después de su descubrimiento, la infección por Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) sigue siendo la causa más frecuente de enfermedades gástricas y duodenales. H. pylori es la causa principal de la gastritis crónica, la úlcera péptica, el linfoma MALT gástrico y el adenocarcinoma gástrico. Recientemente se han publicado varios consensos sobre el manejo de la infección por H. pylori. Las líneas generales del consenso español, del de Toronto y el Maastricht V del 2016 son similares, pero las recomendaciones concretas pueden variar notablemente. Además, las recomendaciones de alguno de estos consensos resultan francamente complejas. El presente documento de posicionamiento de la Societat Catalana de Digestologia es una actualización de las recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia sobre el manejo y tratamiento de la infección por H. pylori. Este documento pretende revisar esta información para hacer unas recomendaciones para la práctica clínica habitual sencillas, concretas y que sean de fácil aplicación en nuestro medio.

This position paper is an update of evidence-based recommendations on the management and treatment of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.

The authors listed were invited by the Catalan Society of Digestology to participate in the drafting and review of the paper on the management of H. pylori infection. Two gastroenterologists (JSD and XC) acted as coordinators. Key questions/recommendations were drafted, which were then reviewed and approved by the participants. The coordinating team formed 4 working subgroups (indications for investigating and treating H. pylori, diagnostic methods, treatment of H. pylori infection and management of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, and treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and/or acetylsalicylic acid [ASA] and/or anticoagulants). The key questions/recommendations were divided among these working subgroups for drafting. The manuscript was finally reviewed and accepted by all the authors and published on the website of the Catalan Society of Digestology as a Position Paper (http://www.scdigestologia.org/?p=page/html/docs_posicionament).

IntroductionMore than 30 years after its discovery, Helicobacter pylori infection is still the most common cause of gastric and duodenal diseases. H. pylori is the main cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma.1–3

There is currently no one optimal treatment option for this infection. For decades, triple therapy combining proton pump inhibitors (PPI), amoxicillin and clarithromycin for 7 or 10 days has been the treatment of choice.4,5 However, over the last few years, this treatment has obtained suboptimal eradication rates6,7 due to increased bacterial resistance, especially to clarithromycin. Therefore, therapy recommendations have been modified.

The new quadruple regimens, with or without bismuth, for 10–14 days together with high doses of PPI are currently considered the treatment of choice. These new regimens have managed to improve the efficacy of treatment, with eradication rates of 90% or higher.

Various consensus reports have recently been published on the management of H. pylori infection.8–12 The guidelines of the Spanish consensus, the Toronto consensus and the 2016 Maastricht V consensus are similar, but specific recommendations can vary significantly. The recommendations of some of these consensus reports are also very complex. In this context, this position paper hopes to revise this information in order to make some simple and specific recommendations for everyday clinical practice that are easy to apply in Spain.

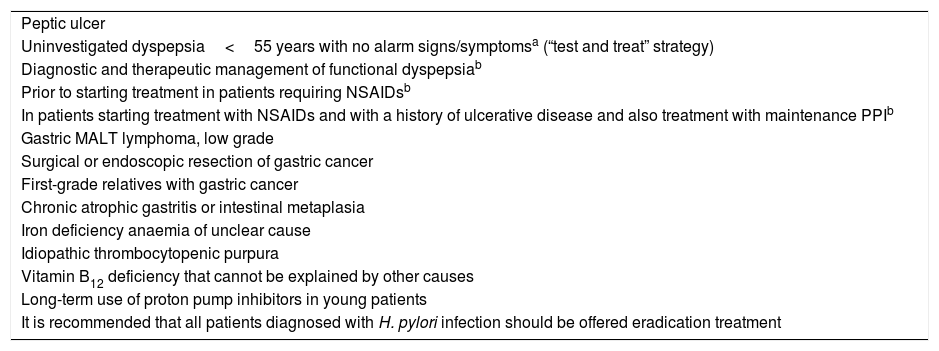

Indications for investigating and treating H. pyloriIndications for investigating and treating H. pylori infection (Table 1) were established several years ago and recent consensus reviews have not made any major changes to such indications.8,10 We will only look at the most controversial aspects or those aspects undergoing change based on new evidence.

Indications for treating Helicobacter pylori infection.

| Peptic ulcer |

| Uninvestigated dyspepsia<55 years with no alarm signs/symptomsa (“test and treat” strategy) |

| Diagnostic and therapeutic management of functional dyspepsiab |

| Prior to starting treatment in patients requiring NSAIDsb |

| In patients starting treatment with NSAIDs and with a history of ulcerative disease and also treatment with maintenance PPIb |

| Gastric MALT lymphoma, low grade |

| Surgical or endoscopic resection of gastric cancer |

| First-grade relatives with gastric cancer |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia |

| Iron deficiency anaemia of unclear cause |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Vitamin B12 deficiency that cannot be explained by other causes |

| Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in young patients |

| It is recommended that all patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection should be offered eradication treatment |

According to the new Rome IV criteria,13dyspepsia cannot be considered to be functional until organic causes have been reasonably ruled out. In Spain, this includes having determined and eradicated H. pylori infection, if detected, and probably ruling out coeliac disease. Therefore, in a patient suspected of having functional dyspepsia, H. pylori infection must be investigated and treated, if present, before definitively diagnosing a functional cause.

The most common indication for eradication in clinical practice will be uninvestigated dyspepsia following the “test and treat” strategy. This strategy involves determining H. pylori infection using a non-invasive test (the urea breath test or a stool test is recommended; see below) and treating it if detected. It must only be used for young patients with no alarm signs/symptoms. The cut-off age for “young patients” is not well established. Criteria for determining this age will depend on the risk of gastric cancer and this varies from one area to the next. Recommendations for using the “test and treat” strategy have varied enormously from 35 to 55 years and European consensus does not specify any age. In our area, which has a low prevalence of gastric cancer, we still recommend using the “test and treat” strategy in patients under the age of 55. However, it is recommended that age should not be used as the only criterion. In patients with a high risk of gastric cancer (immigrant population, smokers, recent-onset dyspepsia, no response to antisecretory therapy, etc.) or with alarm signs or symptoms, an endoscopy will allow the doctor to rule out malignancy and perform histology tests to determine H. pylori infection.

These alarm signs or symptoms may include significant unexplained weight loss, acute and recurrent vomiting, dysphagia or odynophagia, signs of gastrointestinal bleeding (anaemia, haematemesis or melaena), detection of a palpable abdominal mass and jaundice or lymphadenopathy.

The three situations that have resulted in most studies in recent years are eradication in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), eradication in patients with atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia, and patients with long-term treatment with NSAIDs or ASA.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and H. pylori infectionStudies evaluating the association between H. pylori and GORD are of heterogeneous design and population, with results that may seem contradictory.14,15 An inverse association has been shown between H. pylori infection and symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux or oesophagitis and between such infection and Barrett's oesophagus and/or oesophageal adenocarcinoma. This association, however, appears to only be observed in patients diagnosed with atrophic gastritis,16 and the prevalence of atrophic gastritis in the European population is very low (1.8%). A large number of prospective studies and meta-analyses have shown that eradication of H. pylori does not increase the incidence of reflux or oesophagitis symptoms, and does not exacerbate pre-existing symptoms.8,16 Another factor to consider is that, in patients with GORD and H. pylori infection, ongoing treatment with PPI may increase the risk of progression to atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. This effect does not appear to be observed in patients not infected with H. pylori.17

To conclude, in Spain, the presence of GORD should not dissuade doctors from treating H. pylori infection. In young patients who need to receive long-term PPI therapy, it is reasonable to treat H. pylori infection to reduce the risk of progression to atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia.

Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasiaAtrophic gastritis and especially intestinal metaplasia are precursor lesions of gastric cancer. However, in the absence of other risk factors (such as a family history of gastric cancer), the risk of progression to malignancy is very low. There is evidence that eradication of H. pylori infection may reverse atrophic gastritis. Until recently, intestinal metaplasia was thought to be irreversible, but it is possible that this may also be reversible, although this might take a long time and only occur in a subgroup of patients.18 Nevertheless, eradication of H. pylori infection delays and partially decreases the risk of progression to gastric cancer, even in patients who have had an early gastric cancer removed.

Once H. pylori infection had been eradicated, the risk of progression to cancer is very low. It is therefore recommended that H. pylori infection be treated in patients with atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia. There is no evidence to recommend periodic screening endoscopies once the infection has been systematically eliminated. However, the usefulness of such screening cannot be ruled out in some very high-risk patients (extensive intestinal metaplasia in patients with a family history of gastric cancer, for example).

Patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and/or taking NSAIDs/ASA and/or anticoagulantsPatients with gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcerThe presence of H. pylori infection should be assessed in all patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcer and eradication therapy should be prescribed to those infected. H. pylori eradication practically cancels out the risk of ulcerative disease recurrence and complications. Therefore, once eradication has been confirmed, and provided that the patient is not taking NSAIDs/ASA, maintenance PPI therapy is not recommended.19,20 PPIs should, however, be administered until eradication can be confirmed in patients with peptic ulcer who have suffered from gastrointestinal bleeding.

Patients taking NSAIDs/ASANSAID/ASA use and H. pylori infection are independent risk factors for ulcerative disease and its complications. Anticoagulants and other antiplatelet drugs increase the risk of bleeding in patients with ulcerative disease.21,22 Patients with a history of peptic ulcer or its complications have a very high risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding if treated with NSAIDs, ASA or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and are therefore considered to be high-risk patients. Other factors that also increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding are age, corticosteroid therapy or associated comorbidity.

From a practical point of view, it is necessary to evaluate: (a) whether H. pylori eradication will reduce this risk, and (b) whether PPI therapy will modify the need for eradication.

- a)

NSAIDs

Patients with a history of peptic ulcer or complications (low risk): H. pylori eradication significantly reduces the risk of peptic ulcer and ulcer bleeding in patients who are about to start NSAID therapy.23,24 A reduced risk is only observed in those patients who have not previously taken NSAIDs, not in patients who have already received NSAID therapy; in these patients, investigating and treating the infection has no beneficial effect.25,26 A maintenance PPI would be indicated in both groups if the patient had risk factors for gastrointestinal complications.

Patients with a history of peptic ulcer or complications (high risk): eradication is clearly superior to PPI therapy (12.1% vs 34%), but it does not completely eliminate the risk of bleeding.27 It is therefore recommended that diagnosis of H. pylori infection and treatment be assessed in patients starting NSAIDs who have a history of ulcerative disease; maintenance PPI therapy should also be evaluated. In patients who are already receiving chronic NSAID therapy, maintenance PPI therapy is recommended but H. pylori tests or treatment are not required. In patients with a history of NSAID-associated ulcer bleeding, it is recommended that NSAID therapy be discontinued. If this is not possible, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor should be administered with a PPI, regardless of whether H. pylori has been eradicated or not.

- b)

ASA

H. pylori eradication reduces peptic ulcer bleeding in patients taking ASA.28,29 However, a recent meta-analysis indicated that there is not enough evidence to conclude that H. pylori is a significant risk factor for peptic ulcer bleeding in these patients.30 Furthermore, an epidemiological study found no additive effect or interaction effect between ASA and H. pylori infection in patients with ulcerative disease.31 Based on current evidence, systematic eradication therapy does not appear to be necessary in patients taking ASA.

H. pylori eradication reduces the risk of rebleeding in ASA users with a previous history of bleeding due to ulcerative disease. However, there is limited evidence and this is based on studies conducted on the Asian population with a small sample size and a short follow-up time. Therefore, regardless of eradication therapy, maintenance PPI therapy is recommended in patients treated with ASA and with a history of previous ulcer bleeding.

As a result, neither diagnostic testing nor treatment is recommended in ASA users. PPI therapy should be indicated based on the presence of gastrointestinal risk factors. In the case of patients with a previous history of ulcerative disease, maintenance PPI therapy is recommended.

There is no evidence that H. pylori eradication reduces the risk of bleeding in those patients taking cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, other antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants (heparins, vitamin K antagonists or direct-acting anticoagulants). In these patients, systematic eradication therapy is not recommended.22

Diagnostic methodsDiagnostic testing for H. pylori infection is recommended before and after eradication therapy. Non-invasive tests are more easily available, better tolerated and more affordable. In the presence of alarm signs or symptoms, however, an endoscopy and a gastric biopsy should be performed in order to reach a diagnosis. The choice of diagnostic test method will depend, therefore, on its availability and the clinical circumstances of each patient. The diagnostic accuracy of the different tests is affected by medications such as PPI, bismuth and antibiotics.

Non-invasive diagnostic testsThe C13-labelled urea breath test following administration of citric acid is the most sensitive and specific non-invasive test.8,11,32 In Spain, this is considered the test method of choice for diagnosing H. pylori infection before and after treatment.

The stool antigen test is an alternative non-invasive test that can be used if the breath test is not available.33–37 The stool antigen test must be performed using a monoclonal assay approach and this should first be validated in the population where it is to be used. Although it is considered globally to have comparable sensitivity and specificity to the breath test, local validation of the test generally used by the Catalan public health department showed a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 92%, which are lower than even the breath test without citric acid (sensitivity 91%, specificity 99%).38 This sensitivity and specificity are acceptable for diagnosing infection prior to treatment. Therefore, with a prevalence of infection of 60% in patients with dyspepsia, positive and negative predictive values are reasonably good. However, the stool test will have suboptimal performance in post-treatment follow-up, where the prevalence of infection will be less than 10% and the predictive value of a positive result will be around 50%.

The diagnostic reliability of serology is lower than that of the other tests. It varies according to the method used and needs to be validated for the population where it is to be used. Its usefulness is limited because it does not distinguish between active infection and prior exposure. Therefore, its use is not recommended in routine clinical practice.

Invasive diagnostic testsA biopsy of the antrum and the corpus (2 samples from each site) is recommended if the patient requires an endoscopy. This technique allows the infection to be detected with maximum sensitivity and specificity while evaluating the presence of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia.

The rapid urease test is a valid alternative. Its sensitivity and specificity are 90% and 95–100%, respectively, and it can therefore be considered an acceptable alternative to histology. A minimum of 2 specimens (one from the antrum and another from the corpus) is advised. Increasing the number of specimens decreases the likelihood of a false negative result and provides faster results.32 The main causes of false negative results are the presence of blood in the stomach, administration of PPI, antibiotics or bismuth salts, atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia.

Post-treatment follow-up of H. pylori infectionIt is recommended that eradication be confirmed after treatment using a C13-labelled urea breath test following administration of citric acid. This test has a high sensitivity and specificity for confirming H. pylori eradication.

The efficacy of post-treatment stool antigen tests is suboptimal.11,33,37 Current treatments are highly effective (greater than 90%; see below) and the specificity of the stool antigen test used in Spain is 90%. In this context, it is necessary to evaluate and validate other new stool tests that can be used in clinical practice with a specificity that allows post-treatment follow-up. A positive stool test following treatment will have a very low positive predictive value, of around 50%. Therefore, one in every 2 patients with a positive stool test result after treatment will be a false positive. The C13-labelled urea breath test is therefore recommended as the post-treatment method of choice. If a stool antigen test is performed and a positive result is obtained after eradication treatment, it is recommended that persistent infection be confirmed, whenever possible, using a breath test before prescribing second-line treatment.

Serology is not a valid test for proving eradication since it can give positive results even years after eradication.

Use of PPIs, antibiotics or bismuth salts before diagnostic techniquesPPIs should be suspended at least 2 weeks prior to any diagnostic test for H. pylori infection. Antibiotics and bismuth salts should also be suspended at least 4 weeks before the test.

PPIs reduce the density of the infection due to their effect on gastric pH. They can also reduce the sensitivity of diagnostic tests and cause false negative results. This situation is completely reversed 2 weeks after suspending treatment.8,11,32 H2-receptor antagonists have minimal activity and antacids have no activity against H. pylori and therefore do not need to be suspended prior to diagnostic testing. They can be administered as symptomatic treatment when PPIs are suspended.

If the patient is taking antibiotics or bismuth, these should be suspended at least 4 weeks prior to diagnostic testing. These 4-week periods are also considered adequate for detecting the infection again if eradication therapy is not effective. Tests performed 8–12 weeks after treatment may decrease the number of false negatives, increasing the reliability of post-eradication follow-up. More studies are required to clarify this matter.

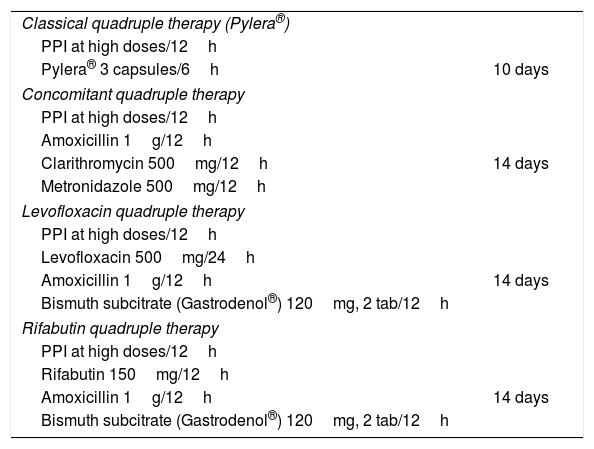

Treatment of H. pylori infectionFirst-line treatmentClassical triple therapy with a PPI, clarithromycin and amoxicillin is not currently recommended because of the variability of its efficacy, which, in most cases, does not reach 80%. The two therapies recommended as first-line treatment are concomitant quadruple therapy for 14 days, or classical bismuth quadruple therapy for 10 days (Pylera®).

Both therapies have demonstrated efficacy equal to or greater than 90% in well-designed studies. The advantage of classical bismuth quadruple therapy is that it requires only 2 drugs, a PPI and Pylera® (a drug that includes metronidazole, tetracycline and bismuth in a single tablet), making it therefore easier to prescribe and explain (Table 2). Its disadvantages are: (a) evidence of its efficacy in Spain is more limited than evidence for the quadruple therapy; (b) the price is moderately higher than the price of concomitant quadruple therapy, and (c) the fact that Pylera® has to be administered 4 times a day. With regard to this latter disadvantage, administration 3 times a day with meals is probably just as effective, although current evidence on this matter is very limited.39 Concomitant quadruple therapy, on the other hand, is given twice a day and its disadvantages are: (a) longer duration; (b) the fact that each of its components must be prescribed separately, making the treatment more difficult to explain; and (c) the large number of tablets of different drugs may make therapeutic adherence difficult.

Dosage and duration of recommended therapies.

| Classical quadruple therapy (Pylera®) | |

| PPI at high doses/12h | |

| Pylera® 3 capsules/6h | 10 days |

| Concomitant quadruple therapy | |

| PPI at high doses/12h | |

| Amoxicillin 1g/12h | |

| Clarithromycin 500mg/12h | 14 days |

| Metronidazole 500mg/12h | |

| Levofloxacin quadruple therapy | |

| PPI at high doses/12h | |

| Levofloxacin 500mg/24h | |

| Amoxicillin 1g/12h | 14 days |

| Bismuth subcitrate (Gastrodenol®) 120mg, 2 tab/12h | |

| Rifabutin quadruple therapy | |

| PPI at high doses/12h | |

| Rifabutin 150mg/12h | |

| Amoxicillin 1g/12h | 14 days |

| Bismuth subcitrate (Gastrodenol®) 120mg, 2 tab/12h | |

Adverse effects are moderate and appear to be similar with both treatments.

According to current data, it seems reasonable to recommend the two treatments at the same level as first-line treatment.

The recommendation is to use a PPI at high doses every 12h, since the more intense the acid inhibition, the more effective the treatment of H. pylori infection.40 Esomeprazole 40mg every 12h offers the most potent acid inhibition with the minimal number of tablets. However, the relatively high cost (€25 per treatment versus €4 with omeprazole 40mg every 12h) means that it is unclear whether this regimen is cost-effective, especially in first-line treatments, and it can therefore not be recommended on a general basis.

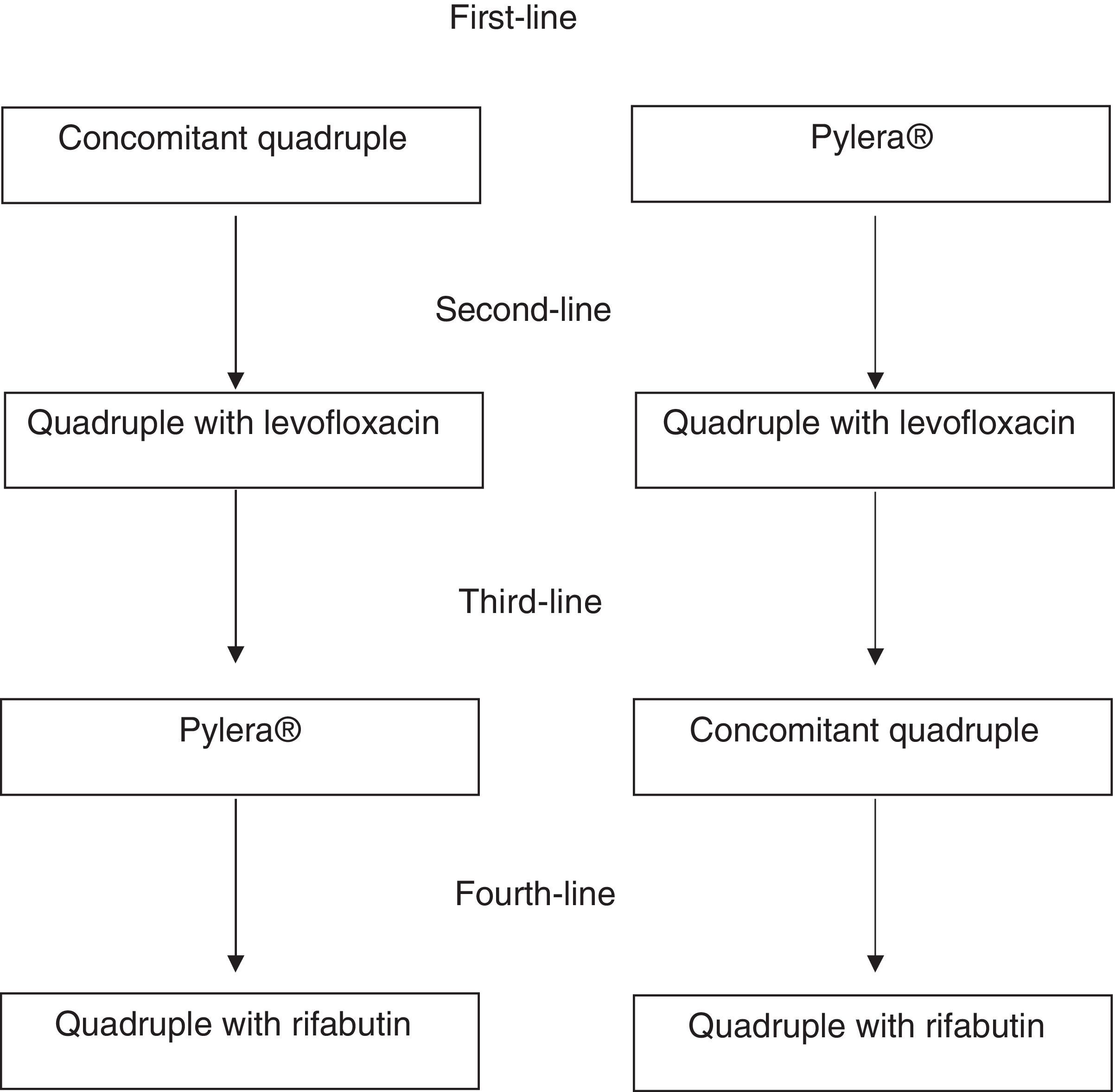

Second-line treatmentA quadruple regimen with high-dose PPIs, levofloxacin, amoxicillin and bismuth is recommended as rescue therapy after the initial treatment has failed (concomitant regimen or Pylera®) (Table 2; Fig. 1). Triple therapy with a PPI, amoxicillin and levofloxacin produces insufficient cure rates, with an average rate of 74%. Therefore, although the number of studies is limited, it is reasonable to recommend a quadruple regimen with high-dose PPIs, levofloxacin, amoxicillin and bismuth as rescue therapy after the initial treatment has failed, whether a concomitant regimen or Pylera® (Table 2). A well-designed observational study demonstrated cure rates greater than 90%.41 Although this is a single study, the results are consistent with clear evidence showing that the addition of bismuth to triple treatments with levofloxacin improves their cure rate by approximately 10%.42 Another equally effective alternative following concomitant therapy failure would be classical quadruple therapy with Pylera® and a high-dose PPI.

Rescue therapy after two treatment failuresGiven the high efficacy of the previous treatments, rescue therapy should only be administered in exceptional cases. The indication for eradication treatment should be reconsidered and adherence to treatment should be thoroughly evaluated. If the patient and the doctor finally agree to a third treatment, the following series of guidelines should be considered:

- a)

Levofloxacin and clarithromycin cannot be used if they were used in previous treatments since the strains that survived will have acquired resistance to these antibiotics and rescue therapy will not be effective. However, metronidazole can be used since a high percentage of patients with in vitro resistance have been shown to be cured, provided that treatments are administered for more than 10 days with high doses of these antibiotics.

- b)

If the initial therapy was concomitant quadruple therapy and the second was quadruple therapy with levofloxacin and bismuth, Pylera® is recommended as rescue therapy.

- c)

If the initial therapy was concomitant therapy and the second was Pylera®, a quadruple therapy with levofloxacin and bismuth is recommended. Finally, after failure of Pylera® and a second regimen with levofloxacin, concomitant quadruple therapy or a combination of high-dose PPIs, amoxicillin, metronidazole and bismuth can be used.

After 3 treatment failures, treatment of infection should only be continued in patients with a very clear indication, such as ulcer (especially with bleeding) or MALT lymphoma, or in patients who are highly motivated to try a fourth treatment and have been fully informed of the situation. Many of the patients experiencing 3 failures (especially with the highly effective therapies that are currently recommended) will have low adherence to treatment. Therefore, adherence to previous treatments and the expected adherence to a new treatment should be assessed very carefully. If the patient finally decides to receive treatment, the recommended regimen includes high-dose PPI, amoxicillin, rifabutin and bismuth (Table 2).

If the doctor has doubts or is not comfortable with the rescue therapy, he should consider sending these patients to a specialised centre for evaluation.

Other aspects of treatment- a)

Cultures do not currently play a routine role in the management of infection in clinical practice.

- b)

The usefulness of probiotics as adjuvants to quadruple therapy has not been evaluated and the addition of a fifth drug complicates dosage and probably adherence and also increases costs. Therefore, their routine use is not recommended in clinical practice.

- c)

In patients who are allergic to penicillin, Pylera® is the treatment of choice. In the event of failure, all of the other recommended regimens (except, of course, concomitant therapy) can be used, but replacing amoxicillin with metronidazole.

- d)

Patients should be warned of the possible side effects of treatment. They should also specifically be warned that faeces may be black when taking bismuth.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Delgado J, García-Iglesias P, Titó L, Puig I, Planella M, Gené E, et al. Actualización en el manejo de la infección por Helicobacter pylori. Documento de posicionamiento de la Societat Catalana de Digestologia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:272–280.