Food allergy has been gaining increasing attention, mostly as causing gastrointestinal and cutaneous reactions. Its role in asthma seems to be under-recognised.

ObjectivesThis study's aim is to explore the frequency of involvement of a common food, namely cow's milk, in childhood asthma.

Methods32 children (5 months to 11 years; median 24 months; mean 34 months) with asthma and a suspected history of cow's milk allergy were studied. They underwent skin prick testing (SPT) and specific IgE (sIgE) testing to whole cow's milk (WCM), casein, α-lactalbumin, and β-lactoglobulin, followed by single-blind oral milk challenge.

ResultsReactions to milk challenge occurred in 12 (37.5%) including wheezing in 5 (41.7%, or 15.6% of the whole group). Children who developed wheezing at the time of challenge were younger than those who had negative challenge (23.0 months vs. 34.8 months). Challenge was positive in 33.3% of subjects who had a positive SPT, and SPT was positive in 50% of challenge-positive subjects. Regarding sIgE, challenge was positive in 26.7% of sIgE-positive subjects, and sIgE was positive in 33.3% of challenge positive subjects. Skin or serum testing with individual protein fractions did not seem to add significant advantage over testing with WCM alone.

ConclusionThis study shows that cow's milk can cause wheezing in children with asthma. Although SPT seemed to be more reliable than sIgE testing, both had suboptimal reliability. It is worth considering possible milk allergy in children with asthma, particularly when poorly controlled in spite of proper routine management.

Food allergy (FA) is common, with a recent meta-analysis showing an overall self-reported prevalence of allergy to peanut, milk, egg, fish, and crustacean shellfish to be 12–13%.1 By a survey, cow's milk allergy (CMA) has an estimated overall prevalence of up to 1.7%, with a higher prevalence of 2% seen in patients less than 5 years old.2 Food allergy can cause a wide variety of manifestations ranging from mild gastrointestinal or cutaneous symptoms to severe anaphylaxis.3

As a cause of asthma, FA seems to be under-recognised, particularly when the causative food is consumed regularly, such as cow's milk (CM) which is the most common food in children. It has been shown that sensitisation and clinical allergy to foods are more common in patients with asthma than in those without asthma.4 Nevertheless, FA is rarely thought of in routine evaluation of patients with asthma.

The objective of this study is to explore the frequency of milk as a cause of wheezing in children with asthma. A secondary outcome can be finding out the degree of reliability of skin prick testing (SPT) and milk-specific IgE (sIgE) in diagnosing CM-induced wheezing in this group.

Materials and methodsWe studied 32 children from our Allergy/Immunology clinic, age 5 months to 11 years (median 24 months, mean 34 months) with an established diagnosis of asthma and suspected CMA by medical history or positive SPT or sIgE. Suspicion by history was based on observation by the parents of a relationship of respiratory symptoms following CM ingestion. The diagnosis of asthma in infants was based on recurrent wheezing with response to bronchodilators, and supported by history of parental asthma or allergy.

Skin prick testing and sIgE levelsEach patient had SPT using commercial extracts and sIgE level measurement to whole CM (WCM) and its three major proteins casein, α-lactalbumin, and β-lactoglobulin. Several other common foods were also included: eggwhite, soy, peanut, wheat, corn, tomato, and apple. The SPT reactivity was compared to the negative control (diluent) and the positive control (histamine 1mg/mL) as 3+, and was considered positive if the reaction was 2+ with a wheal at least 3mm in diameter above the negative control. The level of sIgE was considered positive if it was at least class I according to the manufacturer's scoring system (Pharmacia, currently Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden). Serum total IgE level was also measured, and was considered elevated if it was greater than 2 SD above the mean for age.5

Oral milk challengeAll 32 children, regardless of SPT or sIgE results, underwent single-blind, titrated oral challenge with soybean formula as a placebo or with skim CM disguised in soybean formula. The test was performed under supervision in our allergy clinic according to generally accepted guidelines.6,7 The initial dose was 10–25% of the usually consumed quantity, then increased by doubling at 20–30min intervals. The child was closely observed for any respiratory, cutaneous, or gastrointestinal reactions for about one hour after the last dose. If the result is not clearly positive or clearly negative, it is considered equivocal.

Statistical analysisData were presented by frequencies, range, and mean or median. Chi-square test was applied in comparing frequencies, t-test for comparing two means, and analysis of variance for comparing multiple means. Findings were considered statistically significant if p was <0.05.

ResultsOf the 32 children, SPT or sIgE positivity to WCM, or any of its protein fractions, was found in 13 (40.6%) by SPT, 10 (31.2%) by sIgE, and five (15.6%) by both. The remaining four (12.5%) children had negative SPT and sIgE. Positivity by either SPT or sIgE to another food was noted in 16 (50%) subjects, most commonly egg white in eight.

None of the children reacted to the placebo oral challenge (soybean formula). Cow's milk challenge was positive in 12 of the 32 (37.5%), and another six (18.8%) had equivocal results. Of the 12 children with definite positive milk challenge, five (41.7%, or 15.6% of the whole group) had wheezing, in addition to other symptoms. The other seven (58.3%) challenge-positive children had a variety of symptoms other than wheezing, most commonly exacerbation of atopic eczema.

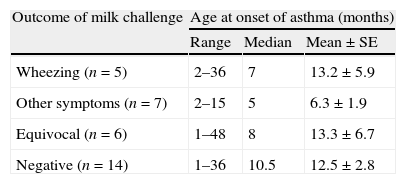

The data on age were analysed according to the age at onset of asthma as well as the age at evaluation. At the time of study, the mean age of subjects who developed wheezing on milk challenge was 23 months, whereas those with a negative challenge had a mean age of 34.8 months (p<0.05). However, the mean age at onset of asthma was 13.2 months in those with wheezing on milk challenge, 6.3 months in those with symptoms other than wheezing (mostly atopic eczema), 13.3 months in those with equivocal challenge, and 12.5 months in those with negative challenge (Table 1). Using analysis of variance, these mean ages were not statistically significant from each other.

Results of oral cow's milk challenge according to age at onset of asthma in 32 children.

| Outcome of milk challenge | Age at onset of asthma (months) | ||

| Range | Median | Mean±SE | |

| Wheezing (n=5) | 2–36 | 7 | 13.2±5.9 |

| Other symptoms (n=7) | 2–15 | 5 | 6.3±1.9 |

| Equivocal (n=6) | 1–48 | 8 | 13.3±6.7 |

| Negative (n=14) | 1–36 | 10.5 | 12.5±2.8 |

Analysis of variance showed no significant difference between these four groups regarding age at onset of asthma.

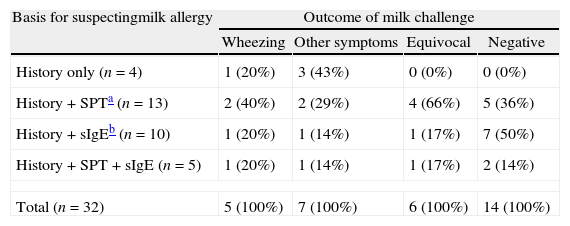

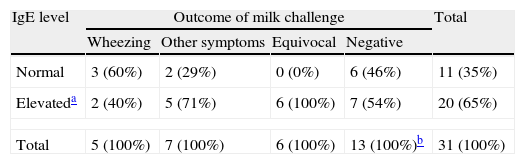

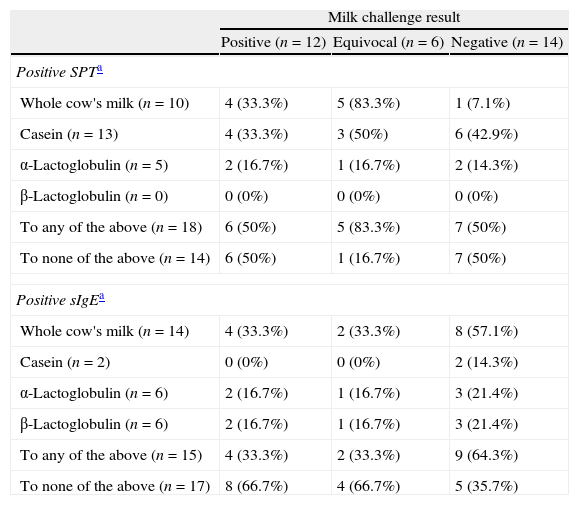

Chi-square testing, with Yate's correction, showed that the likelihood of positive milk challenge did not significantly vary according to the basis of suspecting CMA (Table 2). The majority of the whole group had elevated total IgE, but this was not predictive of the oral challenge outcome (Table 3). None of the three individual milk protein fractions tested, by either SPT or sIgE, were predictive of the oral challenge result (Table 4).

Results of oral cow's milk challenge according to the basis for suspecting milk allergy in 32 children with asthma.

| Basis for suspectingmilk allergy | Outcome of milk challenge | |||

| Wheezing | Other symptoms | Equivocal | Negative | |

| History only (n=4) | 1 (20%) | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| History+SPTa (n=13) | 2 (40%) | 2 (29%) | 4 (66%) | 5 (36%) |

| History+sIgEb (n=10) | 1 (20%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (17%) | 7 (50%) |

| History+SPT+sIgE (n=5) | 1 (20%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (14%) |

| Total (n=32) | 5 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 14 (100%) |

Chi-square testing, with Yate's correction, showed that the outcome of milk challenge did not significantly vary according to the basis of suspecting CMA.

Results of oral milk challenge in children with asthma according to serum total IgE level.

| IgE level | Outcome of milk challenge | Total | |||

| Wheezing | Other symptoms | Equivocal | Negative | ||

| Normal | 3 (60%) | 2 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (46%) | 11 (35%) |

| Elevateda | 2 (40%) | 5 (71%) | 6 (100%) | 7 (54%) | 20 (65%) |

| Total | 5 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 13 (100%)b | 31 (100%) |

The outcome of milk challenge did not significantly correlate with the total IgE level.

Results of oral milk challenge according to testing with whole cow's milk and individual protein fractions by skin prick test (SPT) and specific IgE (sIgE).

| Milk challenge result | |||

| Positive (n=12) | Equivocal (n=6) | Negative (n=14) | |

| Positive SPTa | |||

| Whole cow's milk (n=10) | 4 (33.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| Casein (n=13) | 4 (33.3%) | 3 (50%) | 6 (42.9%) |

| α-Lactoglobulin (n=5) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| β-Lactoglobulin (n=0) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| To any of the above (n=18) | 6 (50%) | 5 (83.3%) | 7 (50%) |

| To none of the above (n=14) | 6 (50%) | 1 (16.7%) | 7 (50%) |

| Positive sIgEa | |||

| Whole cow's milk (n=14) | 4 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 8 (57.1%) |

| Casein (n=2) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| α-Lactoglobulin (n=6) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| β-Lactoglobulin (n=6) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| To any of the above (n=15) | 4 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 9 (64.3%) |

| To none of the above (n=17) | 8 (66.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (35.7%) |

The results of SPT did not match well with those of sIgE (Table 4). Testing for casein was positive in a total of 13 subjects by SPT but in only two by sIgE. On the other hand, testing for β-lactoglobulin was positive in six by sIgE but in none by SPT.

DiscussionIn our study of 32 selected children with asthma and suspected CMA by history or sensitisation, 12 (37.5%) had a positive oral milk challenge, with wheezing in five of them, i.e. 15.6% of the whole group. SPT seemed to be more reliable than sIgE testing, but both had suboptimal reliability. Our figure of 37.5% is very close to those reported in two recent similar studies of 40.9%8 and 41.3%9 based on clinical history of milk reaction and confirmation with open oral challenge. This rate of positive challenge testing emphasises the importance of confirming a diagnosis of food allergy even when strongly suspected by positive history, SPT, and/or sIgE.

In these children with asthma, wheezing was the most common symptom (in 41.7%) to milk challenge, although it was always associated with other symptoms. This is somewhat similar to previous reports. In a study of 163 children with asthma and food allergy, 23.9% were found to have respiratory symptoms during challenge, but only 2.8% had wheezing as the only symptom.10 In another study of subjects with a history of respiratory symptoms related to ingestion of a specific food, 39.9% of those with a positive challenge had wheezing with other symptoms, while 3.0% had wheezing alone during food challenge.11 Therefore, food-induced wheezing in children with asthma is rarely the only symptom.

The total IgE level was not predictive of the oral milk challenge outcome. This is compatible with the findings of other studies. In a study of 143 children under two years of age with suspected CMA, the IgE level varied widely between 5 and 2151kU/L.12

Skin prick test and sIgE positivity were also suboptimal in predicting the result of milk challenge, supporting other researchers’ findings. Costa et al. noted that the sensitivity of SPT and sIgE in predicting positive food challenge was 31.8% and 20.5%, respectively.8 Also Chung et al. reported a sensitivity of 35.5% for SPT and of 14.2% for sIgE.13 Testing with individual major milk protein fractions, by SPT or sIgE, did not increase the reliability above testing with WCM.

It is worth noting that the children in our study were selected with a high likelihood of having wheezing related to CMA. While our small group does not represent the general population, the findings support a role of CMA in childhood asthma. Food sensitisation, to CM in particular, has been reported to be associated with increased asthma severity, leading to greater use of oral corticosteroids and more hospitalisations14,15. Also, asthma is a risk factor for food-induced anaphylaxis.16 and for the persistence of CMA.17

Given the young age of the majority of the children in this study, we were not able to perform spirometry to quantify the degree of airway obstruction in relationship to the milk dose threshold. It is possible that spirometric evaluation would have identified additional subjects with subclinical airway obstruction. Furthermore, food-induced bronchial hyperreactivity may not even be detected by simple spirometry. In a study of 26 patients with asthma and food allergy, methacholine provocation test following food challenge was positive in nine; seven of whom developed respiratory symptoms and two without, indicating subclinical hyperreactivity.18 Similar results were shown with histamine challenge in patients following oral food challenge without significant change in peak expiratory flow rate.19,20

In conclusion, our study showed that CM can cause wheezing in children with asthma. Therefore, it is worth considering a possible role of food allergy in asthma in young children, particularly when asthma is not adequately controlled in spite of proper routine management. Although SPT seemed to be more reliable than sIgE testing, both had suboptimal reliability. A definite decision should depend on performing a titrated oral challenge test.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentRight to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare and the study was not supported with any external funds.