The amounts of Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in gut microbiota are reduced in patients with allergic diseases compared to healthy controls. We aimed to quantify levels of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii amounts using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the gut microbiota of children with allergic asthma and in healthy controls.

Materials and methodsIn total, 92 children between the ages of three and eight who were diagnosed with asthma and 88 healthy children were included in the study and bacterial DNA was isolated from the stool samples using the stool DNA isolation Kit. qPCR assays were studied with the microbial DNA qPCR Kit for A. muciniphila and microbial DNA qPCR Kit for F. prausnitzii.

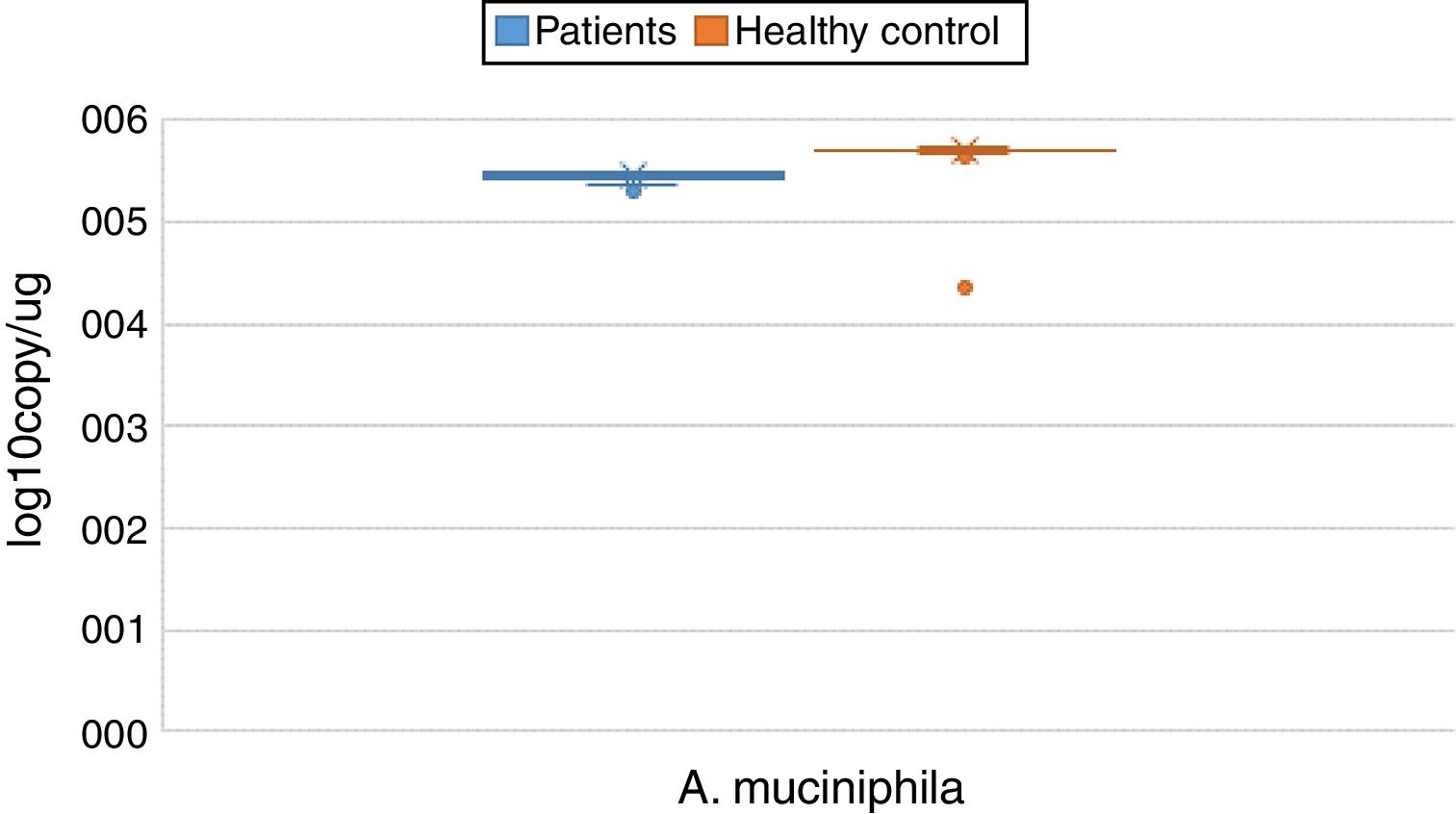

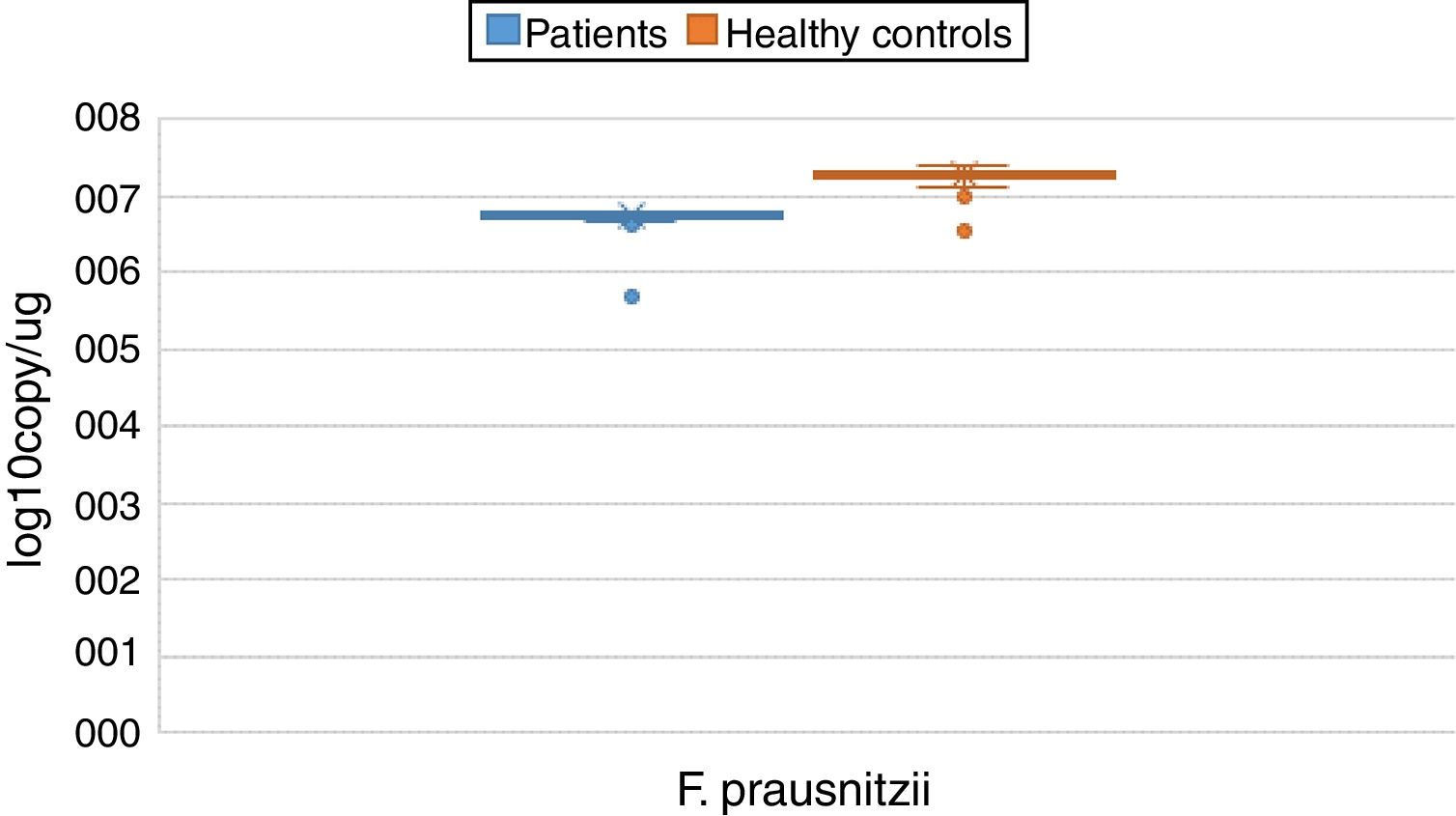

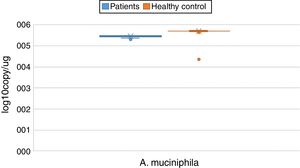

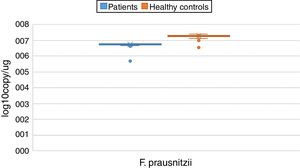

ResultsBoth bacterial species showed a reduction in the patient group compared to healthy controls. A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii were found to be 5.45±0.004, 6.74±0.01 and 5.71±0.002, 7.28±0.009 in the stool samples of the asthma and healthy control groups, respectively.

ConclusionsF. prausnitzii and A. muciniphila may have induced anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and prevented the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-12. These findings suggest that A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii may suppress inflammation through its secreted metabolites.

Allergic diseases, such as asthma, are the most prevalent pediatric conditions, affecting over 300 million people worldwide.1 Asthma is becoming increasingly common and has complex etiologies linked to both genetic and environmental causes,2,3 although its etiopathogenesis is still not fully understood.4 Increased hygiene status and reduced exposure to microorganisms by the immune system in infants have been suggested as possible environmental factors contributing to the formation of allergic diseases such as asthma.5 It is known that an imbalance between the host and metabolically active commensal bacteria, which constitute the human microbiota, is a predominant element in the development of allergic diseases.6,7 Recent studies have suggested that Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii contribute to the formation of these diseases and that the amounts of these bacteria in gut microbiota is changed in patients relative to healthy controls.5,7–12F. prausnitzii was originally classified as Fusobacterium prausnitzii, but as a result of whole genome sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, it was found that they are not closely related to Fusobacterium and more closely related to Clostridium cluster IV (Clostridium leptum group).6 In 2002, Duncan et al. introduced it as F. prausnitzii and proposed the creation of Faecalibacterium as a new genus.13 It has been reported that F. prausnitzii is present in high amounts in the human gut microbiota and represents more than 5% of the total bacterial population alone.5,6A. muciniphila is one of the bacteria most commonly found in human intestinal microbiota and is thought to constitute 3% of human gut microbiota. In 2004, A. muciniphila was isolated by Muriel Derrien, a specialist in the use of mucin by bacterium.14 It has been reported that F. prausnitzii and A. muciniphila have anti-inflammatory effects in the prevention and control of some human diseases. A. muciniphila is thought to exert its anti-inflammatory effects through its metabolites, which control the genes that regulate bowel function, especially in host intestinal epithelial cells. In mouse models, F. prausnitzii has been found to increase anti-inflammatory immune responses by secreting butyrate and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs).15 For these reasons, the aim of this study was to quantify levels of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii amounts using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the gut microbiota of children with allergic asthma and healthy controls.

Material and methodsSample populationThis cross-sectional, case-controlled study was performed between March 2014 and January 2015 at the Pediatric Allergy Clinic. In total, 92 children between the ages of three and eight who were diagnosed with asthma according to international clinical guidelines16 were included in the study. Of the 92 participants, 54 (58.6%) were boys and 38 (41.3%) were girls. The mean age was 5.67±1.24 years. The control group consisted of 88 children from the healthy children clinic of the same center, chosen to reflect the patient group in terms of age, sex distribution, and living standards. Of the 88 control cases included in the study, 52 (59.1%) were boys and 36 (40.9%) were girls. The mean age was 5.43±1.61 years (p>0.05). Exclusion criteria included the use of antibiotics up to two weeks before, and having an infectious disease up to one month prior to study initiation.

Blood and stool samples collectionBlood samples and stool specimens were collected from patients and healthy controls admitted to pediatric clinics using one K2 EDTA tube, one serum separation vacuum tube (Becton Dickinson Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany) and one stool collection tube. These samples were quickly delivered to the Medical Microbiology Laboratory and 1g of stool was stored at −80°C in sterile Eppendorf tubes until further processing. The serum separation vacuum tubes were immediately centrifuged, and the separated sera were aliquoted into new tubes for storage at −80°C until later analysis. The EDTA blood samples were analyzed within two hours.

Detection of total IgE and eosinophil countTotal IgE was detected from sera using Immulite 2000 (Siemens Diagnostics, New York, USA) analyzer with chemiluminescent method according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Sysmex XT-2000i (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) automated hematology analyzer was used to measure eosinophil count from EDTA blood samples via flow cytometry of the proportional count according to the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA isolationBacterial DNA was isolated from the stool samples using the Stool DNA Isolation Kit (cat: 27,600, Norgen Biotek Corp, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The DNA concentration and purity were measured spectrophotometrically using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The DNA samples were stored at −20°C until qPCR experiments for A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii were performed.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)The Microbial DNA qPCR Kit for A. muciniphila (cat: BBID00026A, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and Microbial DNA qPCR Kit for F. prausnitzii (cat: BBID00154A, Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) were utilized according to the manufacturer's instructions. Using a LightCycler 480 II thermocycler, the samples were denatured for 5min at 95°C, followed by 55 amplification cycles of 10s at 95°C and 60s at 60°C. Each run was repeated twice.

Statistical analysisIBM SPSS v 25 was used for all statistical analyses and calculations. The mean (m) and standard deviation (SD) values were used to represent the data. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the averages between the two groups. In terms of statistical significance, p<0.001 was highly meaningful.

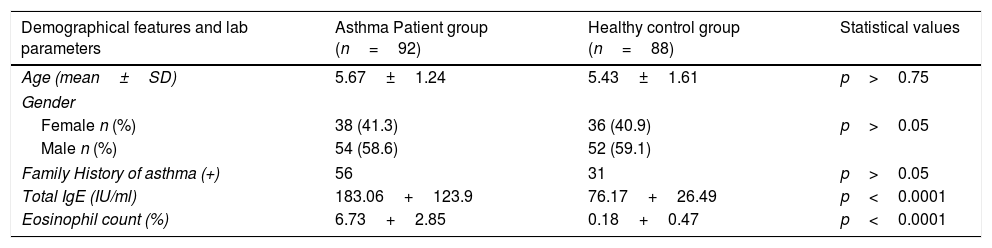

ResultsNo statistical differences were found between individuals with positive and negative family histories for asthma in the patient and control groups (p>0.05). Both the mean IgE level and the mean eosinophil count percentage difference between the patient and control groups were found to be highly meaningful (p<0.0001) (Table 1).

Demographical features and some laboratory parameters of patient and control groups.

| Demographical features and lab parameters | Asthma Patient group (n=92) | Healthy control group (n=88) | Statistical values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 5.67±1.24 | 5.43±1.61 | p>0.75 |

| Gender | |||

| Female n (%) | 38 (41.3) | 36 (40.9) | p>0.05 |

| Male n (%) | 54 (58.6) | 52 (59.1) | |

| Family History of asthma (+) | 56 | 31 | p>0.05 |

| Total IgE (IU/ml) | 183.06+123.9 | 76.17+26.49 | p<0.0001 |

| Eosinophil count (%) | 6.73+2.85 | 0.18+0.47 | p<0.0001 |

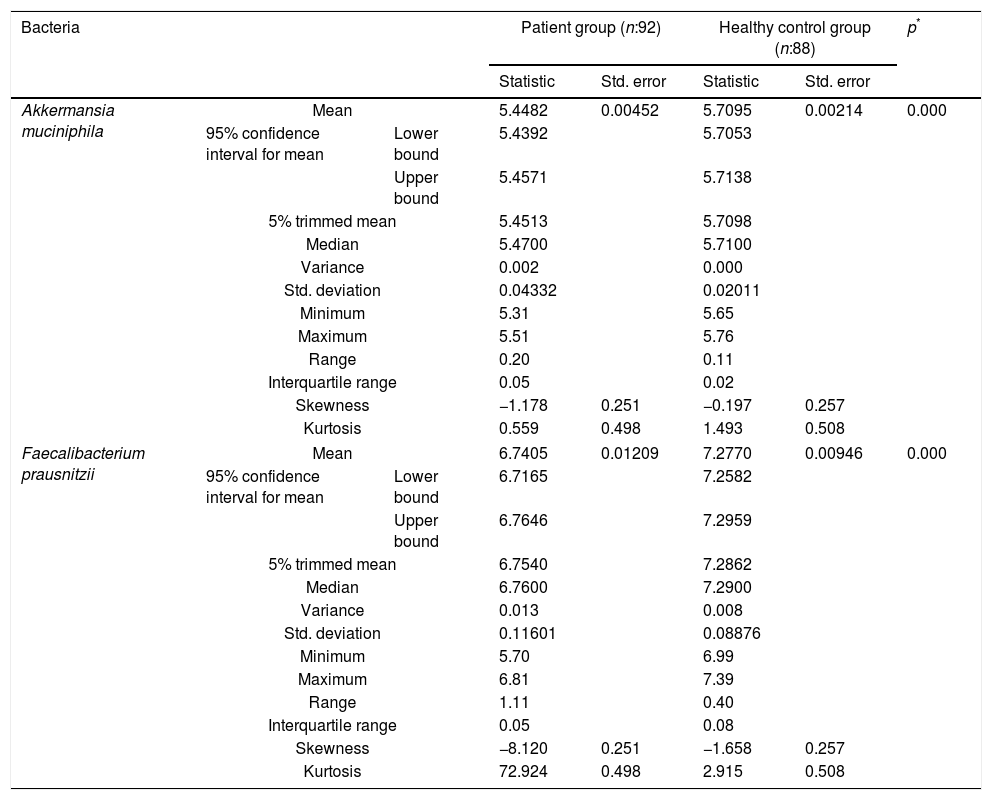

The reductions in the amounts of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii revealed using qPCR for the patient group were highly meaningful compared to the healthy control group (p<0.0001). Both bacterial species showed a decline in the patient group compared to healthy controls. A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii were found to be 5.45±0.004, 6.74±0.01 and 5.71±0.002, 7.28±0.009 log10copy/μg in the stool samples of the asthma and healthy control groups respectively (Table 2).

Distribution of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii in asthma patient and healthy control groups (log10copy/μg).

| Bacteria | Patient group (n:92) | Healthy control group (n:88) | p* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Std. error | Statistic | Std. error | ||||

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Mean | 5.4482 | 0.00452 | 5.7095 | 0.00214 | 0.000 | |

| 95% confidence interval for mean | Lower bound | 5.4392 | 5.7053 | ||||

| Upper bound | 5.4571 | 5.7138 | |||||

| 5% trimmed mean | 5.4513 | 5.7098 | |||||

| Median | 5.4700 | 5.7100 | |||||

| Variance | 0.002 | 0.000 | |||||

| Std. deviation | 0.04332 | 0.02011 | |||||

| Minimum | 5.31 | 5.65 | |||||

| Maximum | 5.51 | 5.76 | |||||

| Range | 0.20 | 0.11 | |||||

| Interquartile range | 0.05 | 0.02 | |||||

| Skewness | −1.178 | 0.251 | −0.197 | 0.257 | |||

| Kurtosis | 0.559 | 0.498 | 1.493 | 0.508 | |||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Mean | 6.7405 | 0.01209 | 7.2770 | 0.00946 | 0.000 | |

| 95% confidence interval for mean | Lower bound | 6.7165 | 7.2582 | ||||

| Upper bound | 6.7646 | 7.2959 | |||||

| 5% trimmed mean | 6.7540 | 7.2862 | |||||

| Median | 6.7600 | 7.2900 | |||||

| Variance | 0.013 | 0.008 | |||||

| Std. deviation | 0.11601 | 0.08876 | |||||

| Minimum | 5.70 | 6.99 | |||||

| Maximum | 6.81 | 7.39 | |||||

| Range | 1.11 | 0.40 | |||||

| Interquartile range | 0.05 | 0.08 | |||||

| Skewness | −8.120 | 0.251 | −1.658 | 0.257 | |||

| Kurtosis | 72.924 | 0.498 | 2.915 | 0.508 | |||

The hygiene hypothesis was first proposed by David Strachan in 1989 and describes an inverse association between infection and atopy.17 Briefly, reduced exposure to microorganisms during childhood shifts the T helper 1 and 2 (Th1/Th2) immune response to Th1, leading to a decrease in the number of allergic disorders.18 The best exposure to microorganisms occurs in the human intestine at the beginning of life and studies have indicated that microbial colonization of the human gastrointestinal (GI) tract during infancy is important for the maturation of the immune system.19 Intestinal microbiota has the ability to regulate metabolic and inflammatory responses and also to modulate changes to the intestinal barrier. Recent studies have revealed associations between the gut microbiota and the development of atopic diseases, including atopic dermatitis, asthma, or rhinitis. However, few studies have investigated the association between reduced fecal microbiota and atopic diseases.20

The colon in the human GI tract hosts approximately 1014 organisms. Molecular analyses have described more than 1000 species, mostly from Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria.21F. prausnitzii, which is a member of the C. leptum group (constituting 16–25% of the fecal microbiota), produces SCFAs, of which butyrate is the major energy source for the colonic epithelium, by fermenting unabsorbed dietary carbohydrates.22 In some diseases (e.g. Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), the C. leptum group, including the dominant F. prausnitzii, are reduced in the fecal microbiota. The number of bacteria and diversity of species are decreased in allergic diseases and these changes are likely to be associated with the dysbiosis that occurs in these diseases.23 Species belonging to the C. leptum group (especially F. prausnitzii) are also now considered as anti-inflammatory commensal bacteria. Loss of butyrate, which has anti-inflammatory activity, may result in more inflammation in the colon.24A. muciniphila is highly involved in the degradation of mucin. A. muciniphila is present in high numbers in the cecum, where mucin is produced. The anti-inflammatory effects of A. muciniphila in the prevention and control of human diseases, including obesity, diabetes type 2, appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome, autism, and atherosclerosis, have been previously reported.11

The relationship between F. prausnitzii and atopic diseases has been previously investigated but studies related to A. muciniphila are limited. For example, Candela et al. (2012) found that there was a decrease in F. prausnitzii and A. muciniphila in the intestinal microbiota of 19 atopic children but also an increase in Enterobacteriaceae in 12 healthy controls aged 4–14 years.12 In another study by Kabeerdoss et al. (2013), C. leptum (especially F. prausnitzii) numbers and diversity were significantly reduced in 20 patients with Crohn's disease and 22 patients with ulcerative colitis relative to 17 healthy controls.22 In a study by Nabizadeh et al. (2017), the frequency and relative amounts of A. muciniphila, C. leptum, and F. prausnitzii in 20 healthy controls were significantly higher than those of 20 patients with chronic urticaria.11 Fieten et al. (2018), analyzed the fecal microbiome of children with atopic dermatitis with or without a concomitant food allergy and found that F. prausnitzii and A. muciniphila discriminate between the presence and absence of food allergies in children with atopic dermatitis (p=0.001).20 The decrease in F. prausnitzii quantity has been linked to several allergic diseases, including atopic dermatitis. In a recent review by Melli et al. (2016), there was a higher count of Bacteroides, a lower count of A. muciniphila, F. prausnitzii, and Clostridium, and a lower bacterial diversity in the microbiota of children with allergies whose intestinal microbiota was assessed at the onset of allergic symptoms.25 The quantities of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii were significantly lower in children with allergic asthma than in healthy control children (p<0.0001) in this study. Only Candela et al. (2012) studied children with asthma (5 of 22 children) and intestinal microbiota of atopic children showed a significant depletion in F. prausnitzii, A. muciniphila.12 However, our results are in parallel with these aforementioned studies, except for the study of Candela et al.12

Other studies suggest that A. muciniphila is associated with allergic dermatitis and that higher concentrations of A. muciniphila also contribute to eczema in infants.26A. muciniphila, as a mucin-degrading bacterium in the intestine, reduced the integrity of intestinal barrier function causing increased uptake of allergenic proteins. Enrichment of a subspecies of the major gut species F. prausnitzii was associated with decreased fecal levels of SCFAs and atopic dermatitis. It was proposed that a high abundance of F. prausnitzii leads to reduced levels of butyrate and propionate and also induces aberrant Th2 cell-mediated immune responses to allergens in the skin.10

In this investigation of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii, we focused on their role in asthma. Interestingly, there is a known collaboration between these two beneficial bacteria. A. muciniphila degrades mucin, while producing acetic acid, propionic acid, and oligosaccharides. These products are used as a substrate by F. prausnitzii to produce butyrate in the intestine and inhibit inflammation in the GI tract, while preventing increased intestinal permeability.27 Antibiotics and chemotherapy frequently cause dysbiosis in fecal bacteria and a decrease in the numbers of Clostridium scindens and F. prausnitzii. In a mouse model, fecal microbiota transplantation resulted in a significant increase in these species known to exhibit anti-inflammatory properties.28 Both butyrate and salicylic acid produced by F. prausnitzii modulate the inflammatory process by inhibiting the production of IL-8 through blocking the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB. In addition, components of F. prausnitzii induce the production of anti-inflammatory IL-10 by peripheral blood mononuclear cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages; consequently, the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-12 is inhibited.29,30

In some disease states, an imbalance in the microbial ecosystem may lead to a microbial imbalance known as dysbiosis.31 Furthermore, F. prausnitzii contains an anti-inflammatory molecule, a 15-kDa protein called microbial Anti-Inflammatory Molecule (MAM) Transfection of MAM cDNA in epithelial cells led to a significant decrease in the activation of the NFkB pathway.32

A. muciniphila is present in approximately 3% of healthy individuals. The main function of A. muciniphila is to degrade mucus using mucolytic enzymes.33A. muciniphila was found to be decreased in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease.34 Recently, one of the outer membrane proteins of A. muciniphila was identified (Amuc_1100). The outer membrane pili-like protein is involved in immune regulation and the enhancement of trans-epithelial resistance.35 The protective effects of these bacteria include the induction of regulatory T (Treg) cells because these cells can reduce inflammation through the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators. An anti-inflammatory milieu is protective against inflammatory diseases such as asthma. This mechanism is in line with studies that found reduced numbers and function of Treg cells in patients with chronic urticaria.11 Allergies (e.g. atopic dermatitis) are caused by Th2-derived immune responses induced by the cytokines IL-4, -5, and -13, which promote the production of various mediators that induce allergic responses. The Foxp3+ Treg cells secrete IL-10 and are known to suppress the excessive activation of Th2 cells, thereby ameliorating allergic responses. Some species of Clostridium, a dominant genus of commensal microbes in the gut, are known to induce Treg cells.5,36 Furthermore, Furusawa et al. (2013) demonstrated that butyrate can induce the differentiation of Treg cells.37 This is of interest because F. prausnitzii is one of the main butyrate-producing bacteria in the intestinal microbiota of the human. A. muciniphila is also involved in the immunological homeostasis of the gut mucosa and gut barrier function, using an outer membrane protein that stimulates IL-10 production. Other mechanisms, such as improving gut barrier function and increasing production of butyrate, may also contribute to a strong anti-inflammatory effect leading to the prevention of atopic diseases35 (Fig. 1).

Fujimura et al. (2016), suggested that neonatal gut microbiome dysbiosis (lower quantity of Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, and Faecalibacterium) drives CD4+ T-cell dysfunction associated with childhood atopy.38 It is also possible that the disruption of the gut microbiome alters the epithelial integrity of the gut, thereby increasing the risk of allergic sensitization through the direct uptake of allergens.39 In animal models of asthma, SCFAs, propionate, acetate, and butyrate have all been shown to protect against airway inflammation and this protective effect has been attributed to the stimulation of Treg cells and dendritic cells capable of preventing Th2-type immune responses1 (Fig. 2).

ConclusionsIn the evaluation of our study, a lower count of A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii was observed in the microbiota of allergic children. F. prausnitzii and A. muciniphila may have induced anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and may prevent the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-12. These findings suggest that A. muciniphila and F. prausnitzii may suppress inflammation through its secreted metabolites.29 We suggest that all of the aforementioned mechanisms that result from the decrease of F. prausnitzii and A. muciniphila may contribute to allergic asthma in our patient group.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.