IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy (CMA) has been shown consistent in milder heated-milk tolerant and severe heated-milk reactant groups in patients older than two years. Little is known whether fermentation of milk gives rise to similar clinical phenotypes.

We aimed to determine the influence of extensively heated and fermented cow's milk on the IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA in children younger than two years.

MethodsSubjects followed with the diagnosis of IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA for at least six months underwent unheated milk challenge. IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated groups were categorised as unheated milk-reactive and tolerant, separately. Unheated milk-reactive groups were further challenged sequentially with fermented milk (yoghurt) and baked milk, 15 days apart. Allergy evaluation with skin tests, prick-to-prick tests and atopy patch tests were performed.

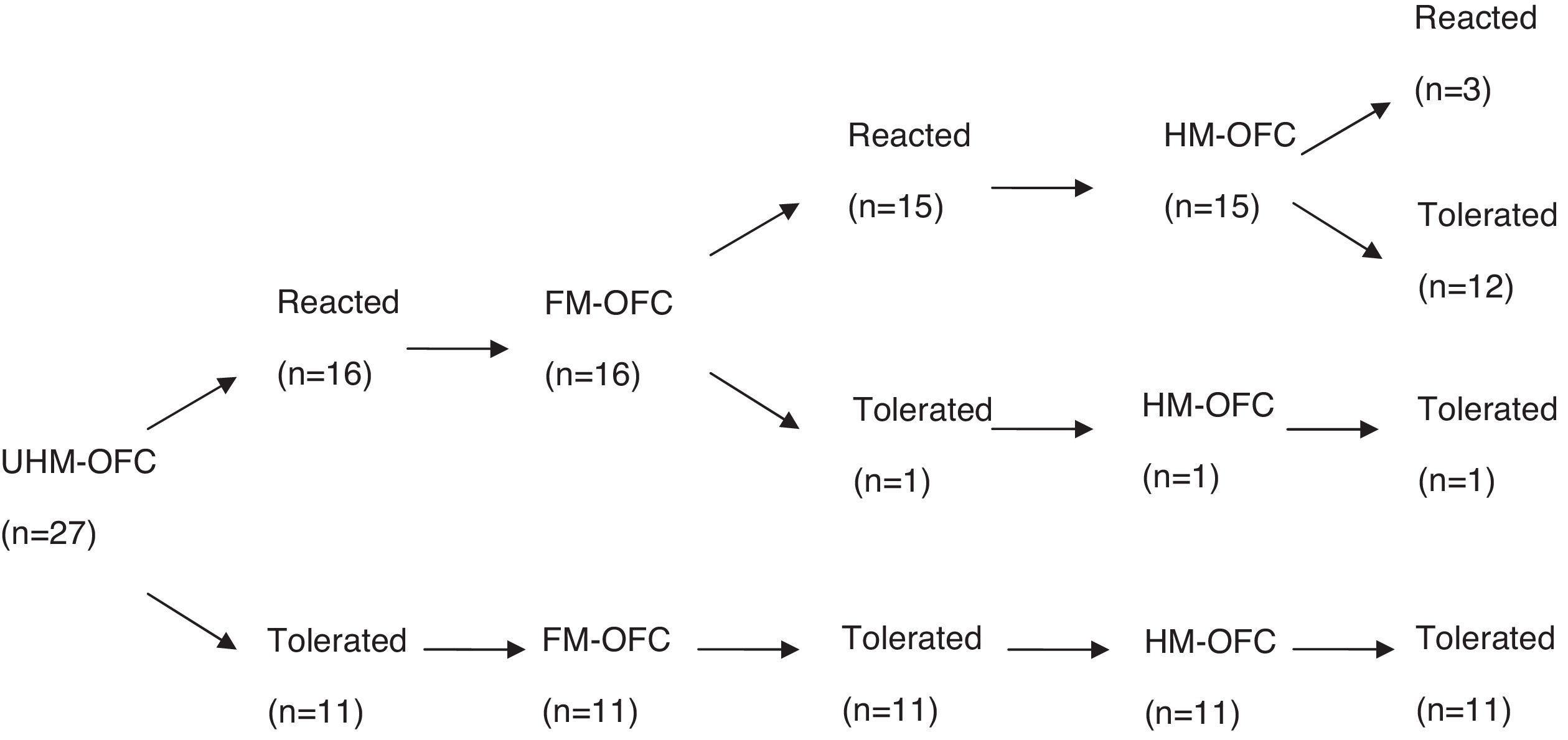

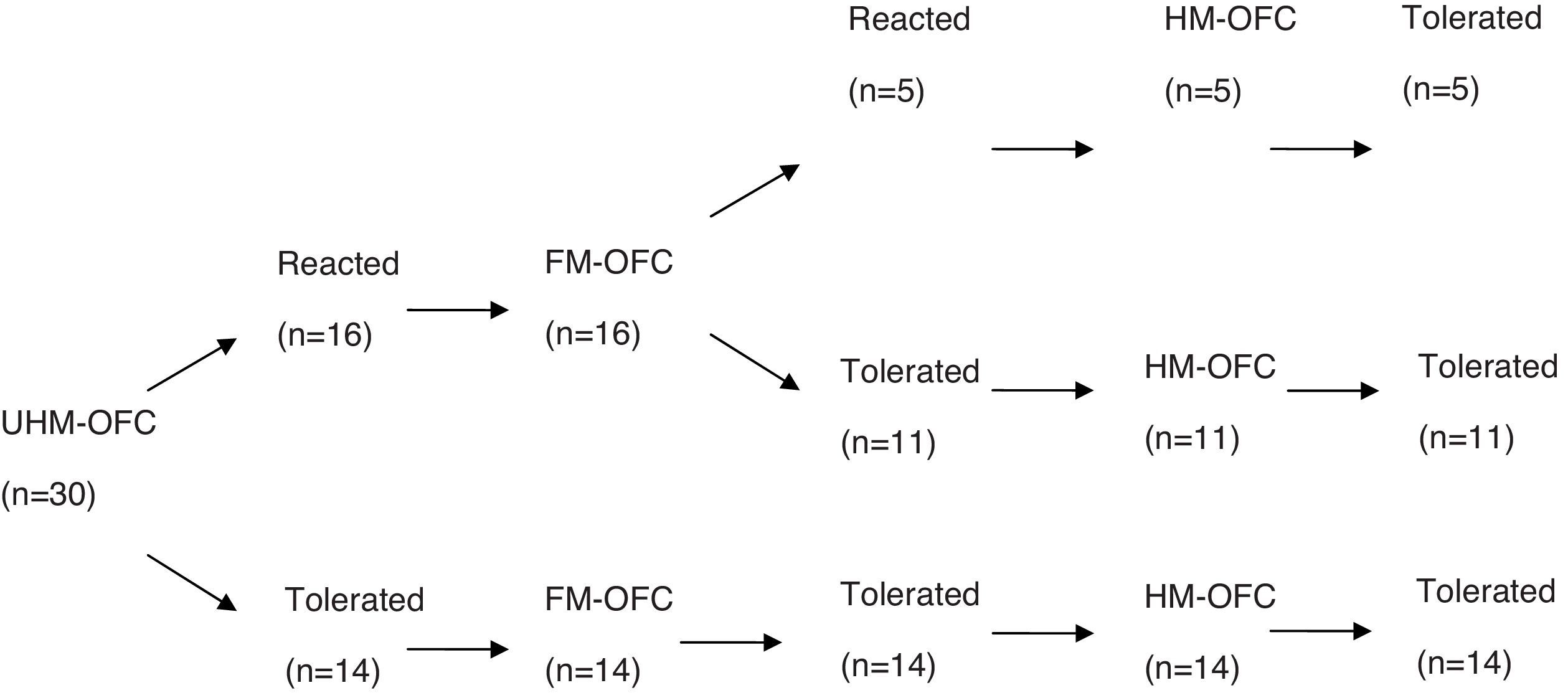

ResultsFifty-seven children (median age: 14 months; range: 7–24 months) underwent unheated milk challenge. Eleven of 27 children with IgE-mediated CMA and 14 of 30 children with non-IgE-mediated CMA tolerated unheated milk. Among subjects who reacted to unheated milk; 15 of 16 subjects (93%) with IgE-mediated CMA also reacted to yoghurt, whereas 11 of 16 subjects (68%) with non-IgE-mediated CMA tolerated fermented milk. Thirteen subjects (81%) of the unheated milk-reactive IgE-mediated group tolerated to heated milk. None of 16 subjects of unheated milk-reactive non-IgE-mediated group reacted to baked milk.

ConclusionThe majority of children under the age of two years with both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA tolerated baked-milk products. Yoghurt was tolerated in two thirds of unheated milk reactive patients suffering from non-IgE-mediated CMA.

Cow's milk allergy (CMA) is the most common food allergy in childhood, affecting about 1.9–4.9% of children worldwide.1 The mainstay of treatment is avoidance of the food and preparation for treatment in the event of an accidental ingestion leading to an allergic reaction. For children on limited diets, nutritional counselling and growth monitoring is recommended as severe complications of a restrictive diet have been reported.2 Although the majority of children with milk allergy become tolerant by school age it causes significant parental stress and health care costs.

In recent years it has been observed that children with IgE-mediated milk allergy are clinically and immunologically heterogeneous, and consist of two different phenotypes. Those with the mild phenotype (almost 75% of children with IgE-mediated CMA) were tolerant of baked-milk products but not unheated milk, whereas those with the more severe phenotype were baked-milk reactive.3

The destruction of conformational epitopes of cow's milk has been suggested as the underlying mechanism of baked-milk tolerance in IgE-mediated milk allergy.4 The inclusion of these foods in diet seems to accelerate development of tolerance to CMA, along with the positive effects on quality of life and nutrition.5

However there are not enough data on whether these observations extend to infancy period and to population of non-IgE-mediated CMA. Furthermore, present information about the effect of yoghurt on the management of IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA is scarce. In the current study we aimed to determine the influence of thermal processing and fermentation of cow's milk on (1) the non-IgE-mediated CMA, and (2) infants and younger age groups with IgE-mediated CMA.

MethodsStudy groupSubjects were recruited from the Pediatric Allergy and Pediatric Gastroenterology Clinics of Kocaeli University Medical Faculty from January 2012 to October 2015. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients.

Subjects between the ages of seven months and two years who have been followed with the diagnosis of IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA for at least six months were included in the study. Diagnosis of IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA had been based on the current international guidelines and included elimination diet and open food challenge manoeuvre, allergen-specific IgE antibody tests and skin prick tests.1

Study designThe study was designed as a cross-sectional study. Subjects underwent unheated milk challenge and they were categorised as unheated milk-reactive IgE-mediated; unheated milk-tolerant IgE-mediated; unheated milk-reactive non-IgE-mediated; and unheated milk-tolerant non-IgE-mediated. Unheated milk-reactive groups were further challenged sequentially with fermented milk (yoghurt) and baked milk, 15 days apart.

Subjects who exhibited no reaction during oral food challenge and consumed at least 100mL cow's milk or yoghurt per day for two weeks were considered as the unheated milk or yoghurt tolerant group, respectively. Subjects who tolerated baked muffin during challenge and ingested at least 1–3 servings per day for two weeks were considered as heated (baked) milk-tolerant.

Open food challengesChallenges were performed openly under physician supervision in the Kocaeli University Pediatric Allergy Unit. Subjects were monitored throughout the challenge and for 2–4h after the completion of the final challenge. Challenges were discontinued at the first objective sign of reaction, and treatment was initiated immediately.

Heated milk challenge was done with muffins, each containing 1.3g milk protein as previously described.3 The muffin was baked at 350°F for 30min in an oven and was administered in four equal portions over 1–2h in subjects older than 12 months while subjects between 6 and 12 months of age were fed eight equal portions over 2h. Unheated and fermented milk (yoghurt) challenges were done with increasing doses up to portions containing 8–10g milk protein according to the previous studies.3,5

Allergy evaluationAllergy evaluation with specific IgE, skin tests, prick-to-prick tests and atopy patch tests were performed before the unheated milk challenge.

Specific IgE testsMeasurement of specific IgE to casein, α-lactoalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, hen's egg, wheat and peanut was performed by using the UniCAP (Phadia UniCAP; Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden); the lower limit of detection is 0.35KIU/L.

Skin prick test (SPT) and prick-to-prick testSPTs were performed with commercial extracts of milk, hen's egg, wheat and peanut (ALK-Abelló, Horsholm, Denmark), with a negative saline and positive histamine control. The size of the skin test response was calculated as a mean of the longest diameter and its longest orthogonal measured at 15min. Prick-to-prick test was performed in the same way using regular milk and yoghurt.

Atopy patch testAtopy patch tests (APT) were performed using a previously reported method in which a drop of fresh cow's milk containing 3.5% fat is placed on filter paper and applied with adhesive tape to the unaffected skin of the child's back using a 12-mm aluminium cup.6 Isotonic saline solution was used as negative control. The occlusion time was 48h. The results were read 20min and 24h after removal of the cups. Antihistamines and anti-inflammatory agents were discontinued at least seven days before the test. Reactions were classified as: mild (erythema and slight infiltration, +); moderate (erythema, infiltration and papules, ++); or severe (erythema, infiltration, papules and vesicles, +++), as previously suggested.6 However, any reaction in the atopy patch test was accepted as positive. APT with yoghurt was done in the same manner using a drop of yoghurt.

StatisticsAll statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Data are expressed as the mean and standard deviation and proportions. For comparison of categorical variables, Fisher's exact test or a chi-square test was used. Differences between numeric variables were tested with a Mann–Whitney U-test. p-values<0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

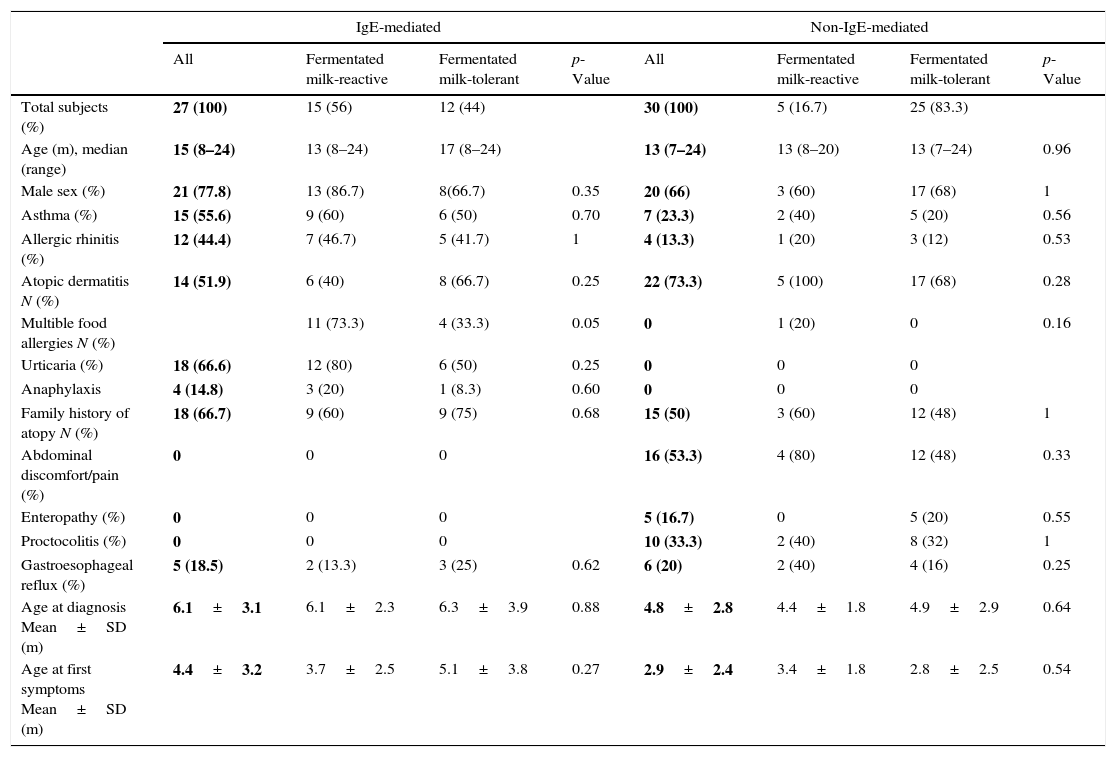

ResultsOral food challenge with unheated milkFifty-seven children (median age, 14 months; range, 7–24 months) underwent unheated milk challenge. Eleven of 27 children with IgE-mediated CMA and 14 of 30 children with non-IgE-mediated CMA tolerated unheated milk (Figs. 1 and 2). Clinical characteristics were not different among the groups (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of study participants.

| IgE-mediated | Non-IgE-mediated | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Fermentated milk-reactive | Fermentated milk-tolerant | p-Value | All | Fermentated milk-reactive | Fermentated milk-tolerant | p-Value | |

| Total subjects (%) | 27 (100) | 15 (56) | 12 (44) | 30 (100) | 5 (16.7) | 25 (83.3) | ||

| Age (m), median (range) | 15 (8–24) | 13 (8–24) | 17 (8–24) | 13 (7–24) | 13 (8–20) | 13 (7–24) | 0.96 | |

| Male sex (%) | 21 (77.8) | 13 (86.7) | 8(66.7) | 0.35 | 20 (66) | 3 (60) | 17 (68) | 1 |

| Asthma (%) | 15 (55.6) | 9 (60) | 6 (50) | 0.70 | 7 (23.3) | 2 (40) | 5 (20) | 0.56 |

| Allergic rhinitis (%) | 12 (44.4) | 7 (46.7) | 5 (41.7) | 1 | 4 (13.3) | 1 (20) | 3 (12) | 0.53 |

| Atopic dermatitis N (%) | 14 (51.9) | 6 (40) | 8 (66.7) | 0.25 | 22 (73.3) | 5 (100) | 17 (68) | 0.28 |

| Multible food allergies N (%) | 11 (73.3) | 4 (33.3) | 0.05 | 0 | 1 (20) | 0 | 0.16 | |

| Urticaria (%) | 18 (66.6) | 12 (80) | 6 (50) | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anaphylaxis | 4 (14.8) | 3 (20) | 1 (8.3) | 0.60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Family history of atopy N (%) | 18 (66.7) | 9 (60) | 9 (75) | 0.68 | 15 (50) | 3 (60) | 12 (48) | 1 |

| Abdominal discomfort/pain (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (53.3) | 4 (80) | 12 (48) | 0.33 | |

| Enteropathy (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (16.7) | 0 | 5 (20) | 0.55 | |

| Proctocolitis (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (33.3) | 2 (40) | 8 (32) | 1 | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux (%) | 5 (18.5) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (25) | 0.62 | 6 (20) | 2 (40) | 4 (16) | 0.25 |

| Age at diagnosis Mean±SD (m) | 6.1±3.1 | 6.1±2.3 | 6.3±3.9 | 0.88 | 4.8±2.8 | 4.4±1.8 | 4.9±2.9 | 0.64 |

| Age at first symptoms Mean±SD (m) | 4.4±3.2 | 3.7±2.5 | 5.1±3.8 | 0.27 | 2.9±2.4 | 3.4±1.8 | 2.8±2.5 | 0.54 |

Among subjects who reacted to unheated milk 15 of 16 subjects with IgE-mediated group (93%) also reacted to yoghurt, whereas 11 of 16 subjects (68%) with non-IgE-mediated group tolerated fermented milk. There was no difference between the fermented milk-reactive and fermented milk-tolerant groups in terms of demographic characteristics (Table 1). Additional egg allergy existed in 60% of the subjects with fermented milk- reactive IgE-mediated CMA. None of the subjects who tolerated fermented milk had additional egg allergy (p=0.014).

Heated milk challengeThirteen subjects (81%) of the unheated milk-reactive IgE-mediated group tolerated heated milk. None of the unheated milk-reactive non-IgE-mediated group reacted to baked milk.

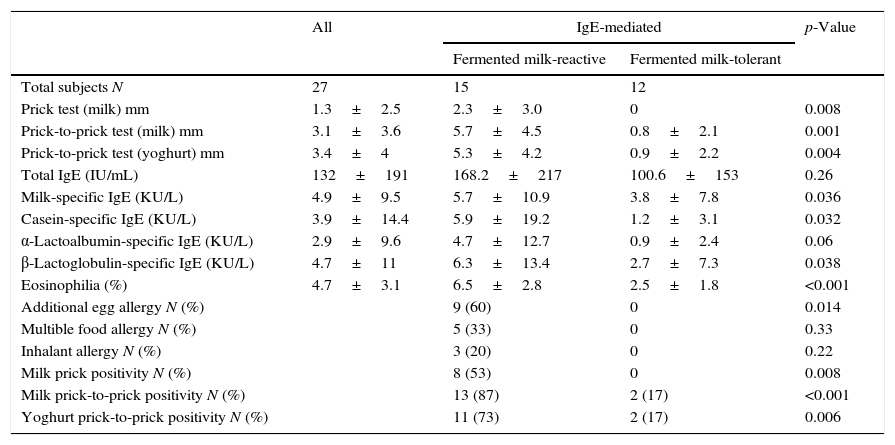

Results of allergy evaluation in the IgE-mediated fermented milk-reactive subjectsThe positivity of cow's milk skin prick test and prick-to-prick test with milk and yoghurt was significantly higher in the fermented milk-reactive group (53%, p=0.008; 87%, p<000.1; 73%, p=0.006, respectively) (Table 2). Children with IgE-mediated CMA who reacted to fermented milk had higher values of specific-IgE levels to cow's milk, casein, and β-lactoglobulin (p=0.036, p=0.032, p=0.038 respectively).

Comparison of laboratory results of IgE-mediated fermented milk reactive and tolerant subjects.

| All | IgE-mediated | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermented milk-reactive | Fermented milk-tolerant | |||

| Total subjects N | 27 | 15 | 12 | |

| Prick test (milk) mm | 1.3±2.5 | 2.3±3.0 | 0 | 0.008 |

| Prick-to-prick test (milk) mm | 3.1±3.6 | 5.7±4.5 | 0.8±2.1 | 0.001 |

| Prick-to-prick test (yoghurt) mm | 3.4±4 | 5.3±4.2 | 0.9±2.2 | 0.004 |

| Total IgE (IU/mL) | 132±191 | 168.2±217 | 100.6±153 | 0.26 |

| Milk-specific IgE (KU/L) | 4.9±9.5 | 5.7±10.9 | 3.8±7.8 | 0.036 |

| Casein-specific IgE (KU/L) | 3.9±14.4 | 5.9±19.2 | 1.2±3.1 | 0.032 |

| α-Lactoalbumin-specific IgE (KU/L) | 2.9±9.6 | 4.7±12.7 | 0.9±2.4 | 0.06 |

| β-Lactoglobulin-specific IgE (KU/L) | 4.7±11 | 6.3±13.4 | 2.7±7.3 | 0.038 |

| Eosinophilia (%) | 4.7±3.1 | 6.5±2.8 | 2.5±1.8 | <0.001 |

| Additional egg allergy N (%) | 9 (60) | 0 | 0.014 | |

| Multible food allergy N (%) | 5 (33) | 0 | 0.33 | |

| Inhalant allergy N (%) | 3 (20) | 0 | 0.22 | |

| Milk prick positivity N (%) | 8 (53) | 0 | 0.008 | |

| Milk prick-to-prick positivity N (%) | 13 (87) | 2 (17) | <0.001 | |

| Yoghurt prick-to-prick positivity N (%) | 11 (73) | 2 (17) | 0.006 | |

Atopy patch test with cow's milk was positive in 6/15 and 2/12 subjects while atopy patch test with yoghurt was positive in 5/15 and 2/12 subjects with fermented milk reactive and fermented milk tolerant IgE-mediated CMA, respectively (p=0.23, p=0.40, respectively).

Among subjects with non-IgE-mediated CMA, atopy patch test with milk and yoghurt were positive in 5/16 and 2/25 of fermented milk-tolerant patients, respectively. None of the five patients with fermented milk-reactive non-IgE mediated CMA had positive atopy patch test with yoghurt whereas in two of them atopy patch test with cow's milk was positive. The difference of the positivity of patch tests with yoghurt and milk was not significant statistically in the fermented milk-reactive and tolerant non-IgE-mediated CMA groups (p=1, p=0.56).

DiscussionThis study which was conducted in infants under the age of two years showed that fermented milk products were tolerated by two thirds of the patients with unheated milk-reactive non-IgE-mediated CMA during follow-up. Additionally, the majority of patients with IgE-mediated CMA, and all patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA, tolerated baked milk products in this age group.

The current standard management of CMA is strict avoidance. There is a growing body of literature indicating that, in some cases, this may not be necessary.5,7 Approximately 70% of children with allergic reactions to milk products can tolerate these foods when they are heated extensively.3 It has presumed that heating results in conformational changes in the proteins, allowing a milder form of the allergy, probably a phenotype that is also more likely to resolve the allergy.3,4 Adding baked foods to the diet can improve quality of life and nutrition. Early evidence suggests that immune responses to the addition of these foods are similar to those seen during successful active immunotherapy and there is an indication of accelerated tolerance.5 However, there are not enough data on whether these observations extend to the infancy period and to the population of non-IgE-mediated CMA. Moreover, little is known about the effect of fermentation on the management of IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated CMA.

A previous study indicating two different phenotypes of IgE-mediated CMA which consist of baked-milk tolerant milder phenotype (75%) and baked-milk reactive severe phenotype was performed on a subset of children older than two years.3 Our results showed that 81% of children younger than two years with IgE-mediated CMA were baked-milk tolerant similar to their older counterparts.

Our study is the first to propose the importance of baked milk on the management of non-IgE-mediated CMA. We found that none of the patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA reacted to baked-milk. Our results show that baked milk can be introduced earlier into the management of children with non-IgE-mediated CMA after diagnosis.

Yoghurt cultures, which ferment and acidify milk, diminish the amount of intact whey protein in milk and may result in tolerance of yoghurt. There are numerous research studies on the effects of fermentation on allergenicity of cow's milk.8–13 The effect of lactic acid fermentation on antigenicity of whey proteins was studied and a reduced binding ability to rabbit polyclonal antibodies was found in a previous study.8 However, when milk allergic patients were skin tested with whey samples from fermented whole milk, the reaction was only slightly attenuated.8 In another study the effect of fermentation by Lactobacilli on the IgE binding ability of β-lactoglobulin was studied using an ELISA inhibition assay.9 The researchers found that fermentation with Lactobacilli had little effect on IgE binding, on the contrary of their previous reports.10 On the other hand, Bu et al. showed that the antigenicity of α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin in skimmed milk could be greatly reduced by Lactobacillus fermentation.12 Lactic acid bacteria, especially combined strains of Lactobacillus helveticus and Streptococcus thermophilus, were found to be the most effective in reducing the antigenicity of α-lactoalbumin and β-lactoglobulin.13

Although many investigators have evaluated the effect of Lactobacillus fermentation on the antigenicity of milk proteins in the laboratory, clinical trials which examine the allergenicity are infrequent. This is the first clinical study aimed to observe the effect of fermentation on CMA after Jedrichowsky et al., to our knowledge.8 We found that the majority (15/16) of children with IgE-mediated CMA reacted to yoghurt while still reacting to milk, similar to Jedrichowsky et al.’s findings. On the other hand, only one third of our patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA (31%) were reactive to yoghurt while still reacting to milk. This implies that yoghurt challenges should not be delayed in the management of the patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA. Yoghurt may be a good alternative food in daily routine of the majority of these children during follow-up.

The reason why the patients with non-IgE-mediated and IgE-mediated CMA differ in the way that they react to yoghurt is not obvious. In the study of Novak et al., the patients that tolerated baked milk became unheated milk tolerant earlier than those that reacted to baked milk.5 The tolerance to baked milk might be the first step prior to the tolerance to unheated milk products. There are no clinical studies about tolerance to fermented milk products in patients with CMA in the literature. We think that tolerance to fermented milk products might be seen before tolerance to unheated milk products. Since this study was a cross-sectional study, our patients with IgE-mediated CMA were in the same age group with those with non-IgE-mediated CMA. It is known that patients with non-IgE mediated CMA become unheated milk tolerant earlier than those with IgE mediated CMA.14 Similarly, our patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA might become tolerant to fermented milk products earlier than those with IgE-mediated CMA.

APT has been recognised as a diagnostic tool for the verification of food allergies in infants and small children with atopic dermatitis and is increasingly being used in the diagnosis of non-IgE mediated CMA.15,16 It targets delayed type hypersensitivity reactions and, is simple to perform, non-invasive and produces minimal side effects. It was suggested that APT might be beneficial in predicting oral tolerance in children with gastrointestinal symptoms suffering from non-IgE-mediated CMA.17 However, poor utility in prediction of outgrowing food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in children was reported.18 It is underlined that reagents, application methods or guidelines for interpretation have not been standardised and for this reason APT is still recommended with the parallel use of multiple other tests for the diagnosis of CMA.19,20 In our study, APT was not indicative for fermented and unheated milk tolerance in both IgE and non-IgE mediated CMA group.

In our study, the negative prick-to-prick tests with milk and yoghurt generally correlate with an increased possibility of tolerance to milk and yoghurt. Prick-to-prick tests using fresh foods were more significant than skin prick tests with commercial extracts. Calvani et al. found that fresh milk in skin prick test shows the highest negative predictive value when comparing commercial extracts.21 Marked differences in protein composition among crude and commercially-available allergen extracts used for skin prick test were shown in another study.22

Casein is a major allergen in cow's milk and retains its allergenicity after extensive heating.23 Casein-specific IgE was considered to identify the optimal candidates for baked milk challenges and to improve management of children with CMA.24 In our study, casein-specific IgE and β-lactoglobulin-specific IgE levels were more significant than α-lactoalbumin-specific IgE for indicating tolerance to milk.

It is known that children with IgE-mediated CMA in early childhood had a significantly increased risk for persistent CMA and development of other food allergies.25,26 We observed egg allergy in over two thirds of our patients with IgE-mediated CMA who reacted to milk while none of the patients in the similar age group with IgE-mediated CMA tolerant to milk had another food allergy. This implies that additional food (especially egg) allergy increases the possibility of persistence of reaction to milk in the IgE-mediated CMA.

The cross-sectional design and the small sample size of the study, especially the small number of patients in the baked milk-active IgE-mediated CMA group, are limitations of our study. Further prospective studies which contain a larger sample size are still needed.

ConclusionProducts prepared with baked-milk may be a good alternative food in daily routine of the majority of children with both IgE- and non-IgE-mediated CMA. In patients younger than two years old, in the IgE-mediated CMA group unheated-milk reactive subjects were also yoghurt reactive. However, two thirds of unheated milk reactive patients with non-IgE-mediated CMA in the same age group tolerated fermented milk. In the light of these observations, fermented milk products may be a nutritional opportunity that should not be delayed in the management of patients suffering from non-IgE-mediated CMA.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.