Alcohol consumption in developing countries is increasing significantly and progressively it has become a major risk factor for chronic liver disease worldwide. As a matter of fact, it has been considered one of the major etiologies of liver diseases.1 Alcoholic persons are thought to be prone to various infections, such as hepatitis C, in which the severity of damage is related with ethanol consumption.2 According to epidemiological data, alcohol related liver deaths is one of the leading causes of mortality in western and latinoamerican countries.3

Recently, research on alcohol effects has been growing increasingly from several points of view, mainly in terms of health benefits and risks. For a long time, alcohol intake was conceived as representing some kind of “dangern” for human health. Indeed, the main clinical recommendation to patients who suffer liver disorders have been lies on complete abstinence from alcohol.4 However, it has been suggested that modest alcohol consumption, that is to say up to two drinks per day, was associated with less severity of fibrosis and hepatocellular injury in steatohepatitis.5 Whether patients with liver disease should abstain from alcohol or rather be allowed modest alcohol consumption remains still unknown.

There are certain clinical alcohol effects which have been examined in several chronic conditions such as obesity, chronic viral hepatitis C, non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), non alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and alcoholic liver disease (Tables 1 and 2). Clinical studies in viral hepatitis C have shown a progressive liver damage effect at histological levels,6 as well as high levels of hepatic activity markers; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and biochemical marker of alcohol intake, gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), which were related to a more severe grade of injury in chronic hepatitis C patients.7 However, an increase of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA titers2 has been observed as well as an increase in viral replication rate according to the drinking patterns.8

Comparison of studies investigating alcohol harmful effects in liver diseases.

| Study | Population | Dose | Study design | Harmful effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oshita, et al. 1994. | 53 patients with chronic HCV hepatitis. 16/37 habitual/non-habitual drinkers. | IFNα/daily therapy ≥ 60g/day ethanol for 5 years. | Clinical study. | Alcohol potentiated HCV replication in patients with hepatitis C. |

| Cromie, et al. 1996. | 45 patients with chronic hepatitis C. | Two groups: alcohol intake of > 10g/day and ≤ 10g/day. | Follow-up study alcohol intake moderation. | Alcohol aggravates hepatic injury in chronic hepatitis C patients, and viral load. |

| Pessione, et al. 1998. | 233 chronic hepatitis C carriers with alcohol consume. | < 140g/per week in 80% patients. | Cross-sectional study. | Direct role of alcohol on HCV replication and/or HCV clearance in association with a poor response to interferon therapy. |

| Hézode, et al. 2003. | 260 patients with chronic hepatitis C. | 31-50 g/day in men and 21-50 g/day in women. | Prospective study. | Moderate alcohol consumption may aggravate histological lesions in patients with chronic hepatitis C. |

| Ruhl, et al. 2005. | 13,580 adults from the NHNES 1988-1994 (overweight and obese persons). | > 2 drinks per day. | Population based study. | Overweight and obesity increased the risk of alcohol-related abnormal aminotransferase activity. |

HCV: hepatitis C virus. IFNα: interferon alpha. NHNES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ab: antibody.

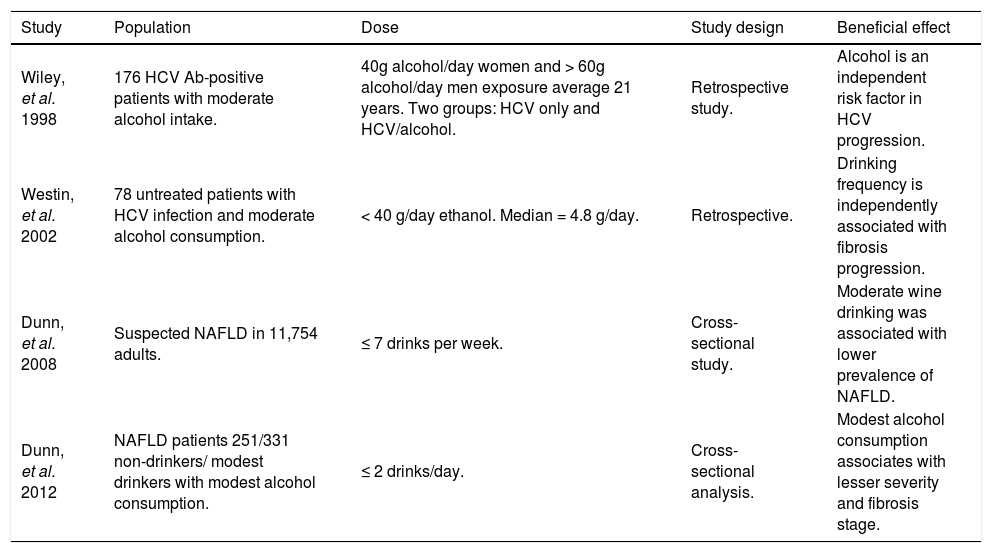

Comparison of studies investigating alcohol beneficial effects in liver diseases.

| Study | Population | Dose | Study design | Beneficial effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiley, et al. 1998 | 176 HCV Ab-positive patients with moderate alcohol intake. | 40g alcohol/day women and > 60g alcohol/day men exposure average 21 years. Two groups: HCV only and HCV/alcohol. | Retrospective study. | Alcohol is an independent risk factor in HCV progression. |

| Westin, et al. 2002 | 78 untreated patients with HCV infection and moderate alcohol consumption. | < 40 g/day ethanol. Median = 4.8 g/day. | Retrospective. | Drinking frequency is independently associated with fibrosis progression. |

| Dunn, et al. 2008 | Suspected NAFLD in 11,754 adults. | ≤ 7 drinks per week. | Cross-sectional study. | Moderate wine drinking was associated with lower prevalence of NAFLD. |

| Dunn, et al. 2012 | NAFLD patients 251/331 non-drinkers/ modest drinkers with modest alcohol consumption. | ≤ 2 drinks/day. | Cross-sectional analysis. | Modest alcohol consumption associates with lesser severity and fibrosis stage. |

HCV: hepatitis C virus. Ab: antibody. NAFLD: Non alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Furthermore, alcohol intake has been associated with a poor response to interferon therapy in patients with viral hepatitis B9 and viral hepatitis C.2,6,10 The way in which this biological phenomenon develops is not well known. Evidence supports, however, the hypothesis that alcohol may pontentiate hepatitis C viral infection by immune-mediated factors probably due to a change in cell-mediated immunity and modulated interferon therapy,2 impairing the immune system’s viral response.10

It is well known that alcohol metabolism is considered to be the principal cause of liver damage. The study of alcohol metabolism includes several complex mechanisms and endotoxins involved in liver injury.1 There are 2 main pathways of alcohol metabolism, alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P-450 2E1 (CYP2E1). Alcohol dehydrogenase is the main participant in alcohol metabolism, its primary effect focuses on alcohol oxidization to acetaldehyde, and it is considered the key toxin in alcohol-mediated liver injury by promoting cellular damage, inflammation, extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrosis.11 Acetaldehyde binds through covalent bonds to proteins and DNA forming adducts such as malondialdehyde, which directly affects cell functions and contributes to liver injury by lipid peroxidation of the cellular membrane.12 On the other hand, alcohol oxidation also occurs via cytochrome P450 to cause tissue injury by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide ions.13 This event coupled with a decrease in cellular antioxidant levels in blood and liver, like glutathione (GSH),14 lead to enhaced tissue injury.

The convertion of alcohol to acetate enhances his-tone acetylation at specific cytokine gene promoters, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); this regulates the protein synthesis and promotes inflammation in acute alcoholic hepatitis.15 Furthermore, the role of alcohol has been related to metabolism in mitogenesis activation, oncogenesis,16 and as an immuno modulator and apoptosis inhibitor.17

These inflammatory events have been described at several hepatic lineage cells.18,15 In hepatocytes, ROS is generated from both mechanisms, alcohol deshidrogenase and CYP2E1 pathways, while nitric oxide (NO) and reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase are produced by Kupffer cells.18 These mechanisms affect several macromolecules, such as proteins, lipids and DNA. The biological importance in cellular systems lies in their participation in certain molecular pathways that converge in the development of alcoholic liver disease.1

Novel and promising findings underpin that alcohol could benefit some particular pathological conditions.19,20 Several studies demonstrated that there is not a correlation of HCV RNA levels between drinking patients and not drinking patients.10,7 In fact, it has been postulated that the damaging effect of ethanol and HCV is simply additive.21 This evidence points out the idea that HCV and not alcohol primarily mediated hepatocyte damage, suggesting that alcohol intake is an independent risk factor in the clinical and histological progression of HCV infection.10

Dose consumption seems to be a key point in determining if alcohol promotes a benefit or risk in liver disease patients (Tables 1 and 2). A modest alcohol consumption seems to protect the liver from NASH and NAFLD5 (Table 2), meanwhile higher alcohol doses lead to damage effects22 (Table 1). However, it has been suggested that drinking frequency might be more important than the quantity consumed on each occasion,23 as well as the quality of alcohol,24 where Gronbaek et al. suggests that drinking wine could promote a lower risk of developing alcoholic cirrhosis as compared to drinking beer or spirits in a metabolic syndrome swine model.25 Unfortunately, there is insufficient evidence to establish whether quality of alcohol had a major impact on disease burden. Moreover, consumption of alcohol without food was associated with an increased prevalence of alcohol related liver disease.24

Despite the strong evidence which supports the potential benefits of alcohol consumption, we should mention that overweight and obesity have been well described to increase the risk of alcohol-related abnormal aminotransferase activity.26 In animal models, it has been shown that this condition worsens glucose metabolism by altering activation of the in sulin signaling pathway in the liver and skeletal muscle.27,28

It is important to mention that alcohol consumption not only impacts in liver pathologies, it has also suggested a direct relation between moderate alcohol consumption and insulin sensitivity29 suggesting that alcohol could have a role in reduced risk of diabetes.30,31,32 In addition, it has been related to cardiovascular events associated with liver enzymes and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), which predisposed NAFLD patients to develop metabolic disorders concomitant with a significant risk for coronary artery disease.30,33,34 However, moderate alcohol consumption was associated with a decreased incidence of heart disease in persons with diabetes.32

Low levels of alcohol intake have been inversely associated with total mortality in both men and women,35 it seems that benefit depended in part on age, since mortality (relative risk) of several cancer diseases was higher in drinking adults, but in middle-aged and elderly population, moderate alcohol consumption slightly reduced overall mortality.36

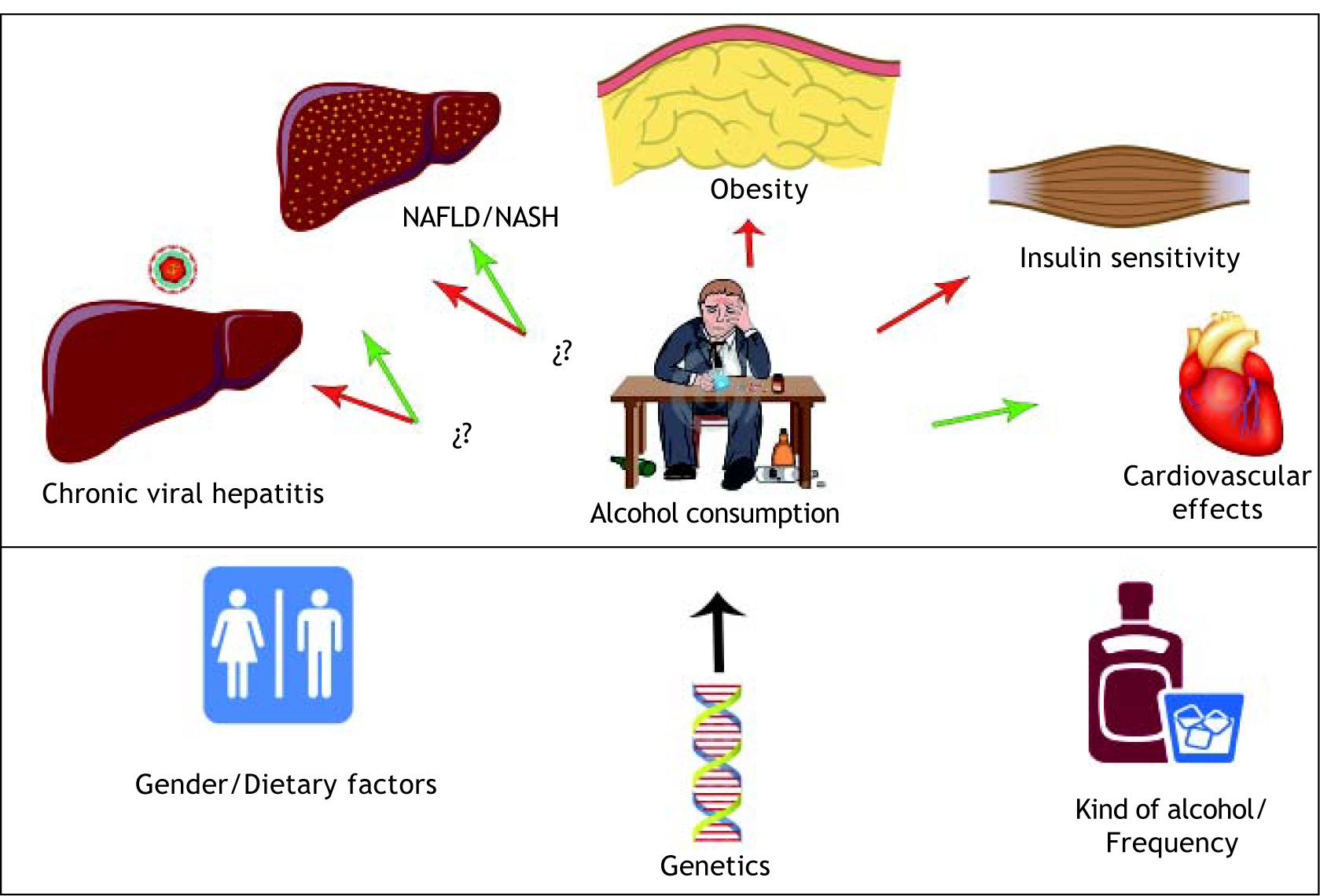

In clinical conditions where several variables impact disease progression (Figure 1). It is difficult to determine which factor has the main role in enhancing disease progression; gender,37 drinking patterns, kind of alcohol, quantity, obesity, dietary factors,38 clinical condition, non-sex-linked genetic factors and smoking,37,39,40 It seems that alcohol intake per se does not determine liver damage and should be considered a multifactorial disease. Until further data from rigorously conducted prospective studies become available, multiple factors must be taken into consideration in order to evaluate whether a patient is able to consume alcohol or not.

Further studies of cellular and molecular mechanisms should be contemplated in order to provide a better understanding of the different mechanisms involved and which will contribute to define the important steps along the therapeutic pipeline by identifying potential novel and specific therapeutic targets.