Introduction. Liver transplantation (OLT) for primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is characterized by disease recurrence of up to one third of patients. The diagnosis of recurrence requires a cholestatic profile and a typical histology representing a challenge for transplant hepatologists. Antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) establish the initial diagnosis, persist after OLT, and are thus of limited value for the diagnosis of recurrence. Aim of this analysis was to identify serological parameters associated with recurrent PBC.

Patients and methods. OLT performed between 1992 and 2006 at Hannover Medical School were evaluated retrospectively including histology before and after OLT, autoimmune serological parameters and clinical characteristics.

Results. Between 1992 and 2006 72 patients underwent OLT with histologically confirmed PBC. Median follow up was 123 months. AMA persisted in 55 (767) patients. Anti-parietal cell antibodies (PCA) were detectable in 41% of the patients before and 47% after OLT. Liver biopsies were obtained in 34 patients post OLT upon clinical suspicion, and recurrent PBC diagnosed in 28% after a mean of 71 months (range 13-161). Anti-PCA were detected in 100% of patients with recurrence before and following transplantation, 54% of patients with anti-PCA before OLT developed recurrence during follow-up. There were no differences in immunosuppressive regimen.

Discussion. Although unspecific for the diagnosis of PBC, anti-PCA prevalence increased after OLT, and was 100% in patients with recurrent PBC. Recurrent PBC developed in 54% of patients with anti-PCA before OLT suggesting a diagnostic role of anti-PCA as a simple and cost effective marker of recurrence.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by the destruction of interlobular and septal bile ducts, leading to the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis.1 Genetic susceptibility as a predisposing factor for PBC has been suggested and involves MHC and non-MHC genes.2 In addition environmental factors have been suggested to include infectious and environmental etiologies.3,4 The diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical features, abnormal liver biochemical pattern in a cholestatic picture persisting for more than six months and presence of detectable antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) in serum directed against PHD-E2 antigen.5,6 Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) remains the definitive treatment for decompensated liver disease secondary to PBC. OLT for primary biliary cirrhosis is characterized by disease recurrence with typical clinical, biochemical, and histologic changes in up to one third of pa-tients.7 Although the presence of recurrent PBC does not appear to affect either graft or patient survival rates as severely as in HCV and PSC, the diagnosis of recurrence requires a cholestatic profile and a typical histology representing a challenge for transplant hepatologists. Previous studies identified donor and recipient age and warm/cold ischemic time as a risk factor for PBC recurrence.1,8 While the initial diagnosis is based on antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA), which persist after OLT9,10 they are thus of limited value for the diagnosis of PBC re-currence.11 Aim of this study was to identify autoimmune serological parameters associated with recurrent PBC.

Patients and MethodsAll patients who previously had undergone liver transplantation at the Hannover Medical School between 1992 and 2006 were evaluated. Of those, 72 patients underwent liver transplantation with histologically confirmed PBC. Post-transplantation immunosuppressive therapy included cyclosporine A or tacrolimus, corticosteroids and/or mycophenolate mofetil. Cyclosporine A doses were adjusted to maintenance blood levels between 100-200 ng/mL. Tacrolimus doses were adjusted to maintenance blood levels between 5-15 ng/mL. Methylprednisolone was given as a bolus injection of 500 mg at the time of reperfu-sion, and 250 mg were administered six hours post-operatively. Prednisolone was started at 100 mg orally on day 1 after OLT and then individually tapered down to 5-7.5 mg. In addition, some patients also received azathioprin, mycophenolate mofetil or monoclonal anti-interleukin-2 receptor antibodies.

All 72 patients with histologically confirmed PBC were analysed for the following autoimmune serolo-gical parameters: antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti parietal cell antibodies (anti PCA), anti-soluble liver antigen (SLA), anti liver-kidney-microsome antibody (LKM) and anti-pyruvate dehydrogenase-E2 (anti PHD-E2) before and after OLT. Indirect immunofluorescence was used for the detection of AMA, anti PHD-E2, ANA, PCA, SLA, anti-LKM antibodies as previously described.12 Titers above 1:80 were considered to be significantly positive. Additionally, we studied im-munosuppressive therapy and outcome of these patients.

Gold standard for the diagnosis of recurrent PBC was a liver biopsy demonstrating the characteristic histologic features. Patients did not receive routine biopsies, but the indication for liver histology was indication-based. Recurrent PBC was based on the presence of epitheloid granulomas, florid bile duct lesions, bile duct injury, and lymphoid aggregates in liver specimens, and biochemical cholestasis.11 Other pathology or disorders such as acute and chronic rejection, graft versus host disease, biliary obstruction, cholangitis and other infections, viral hepatitis or drug toxicity were excluded.

Furthermore during pre OLT diagnostic work-up all patients received an upper intestinal endoscopy, which included a histological assessment of gastric mucosa in all 72 patients and therefore the opportunity to detect H. pylori infection. H. pylori was identified following standard microbiology and biochemical techniques.

ResultsPatient and graft survivalBetween 1992 and 2006 72 patients (68 female, 4 male) underwent OLT with histologically confirmed PBC. Median follow up was 123 months. Five patients died because of sepsis (2), cerebral vascular attack (1), or cholestatic liver failure (2) within 11 years after OLT, 2 patients required re-transplantation because of bile duct necrosis and thrombosis of the hepatic artery (11 months and 1 month after liver transplantation). Overall patient survival was 85.67.

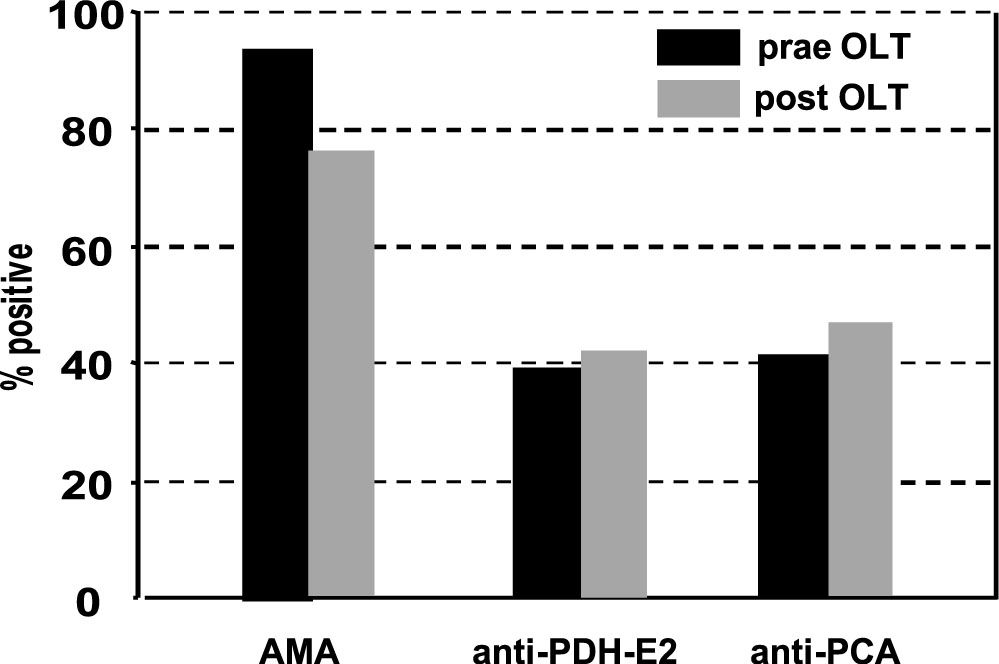

Autoantibodies after liver transplantationNearly all patients (94%) were AMA positive before liver transplantation, while only 6% were negative before OLT. Interestingly, AMA persisted in 55 (76%) patients after OLT Figure 1, Table 1A). Anti-PDH-E2 directed AMA was positive in 26 out of 66 (39%) patients before and in 27 out of 64 patients (42%) after OLT.

Detection of antibodies before and after orthotopic liver transplantation in patients with PBC. Indirect immunofluorescence was used for the detection of AMA, anti PHD-E2, PCA, antibodies as previously described.7 There was no significant difference in detection of AMA, anti PHD-E2 or PCA.

Characteristics and antibody profile of 72 patients with PBC who underwent liver transplantation.

| Age (in years): SI (range 25-67) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex: 68 female/4 male | ||

| Median follow up (in moths): 123 | ||

| pre | post | |

| AMA positive | 68/72 (94%) | 55/72 (76%) |

| ANA positive | 17/72 24%) | 21/72 (29%) |

| AntiPDHE2 positive | 17/72 (24%) | 21/72 (29%) |

| antiPCA positive | 28/68 (41%) | 34/72 (47%) |

| bilirubine (mg(dl_ | 5.2 (1-52) | 1.8 (0.1-33) |

| biopsy available | 72/72 (100%) | 34/72 (47%) |

| H. pylori positive | 28/72 (38.8%) | n.d |

ANA were detectable in 17 out of 72 patients before and in 21 patients after OLT (Table 1A). 28 out of 68 patients had anti-parietal cell antibodies (PCA, 41%) before and 34 out of 72 patients (47%) had PCA after OLT.

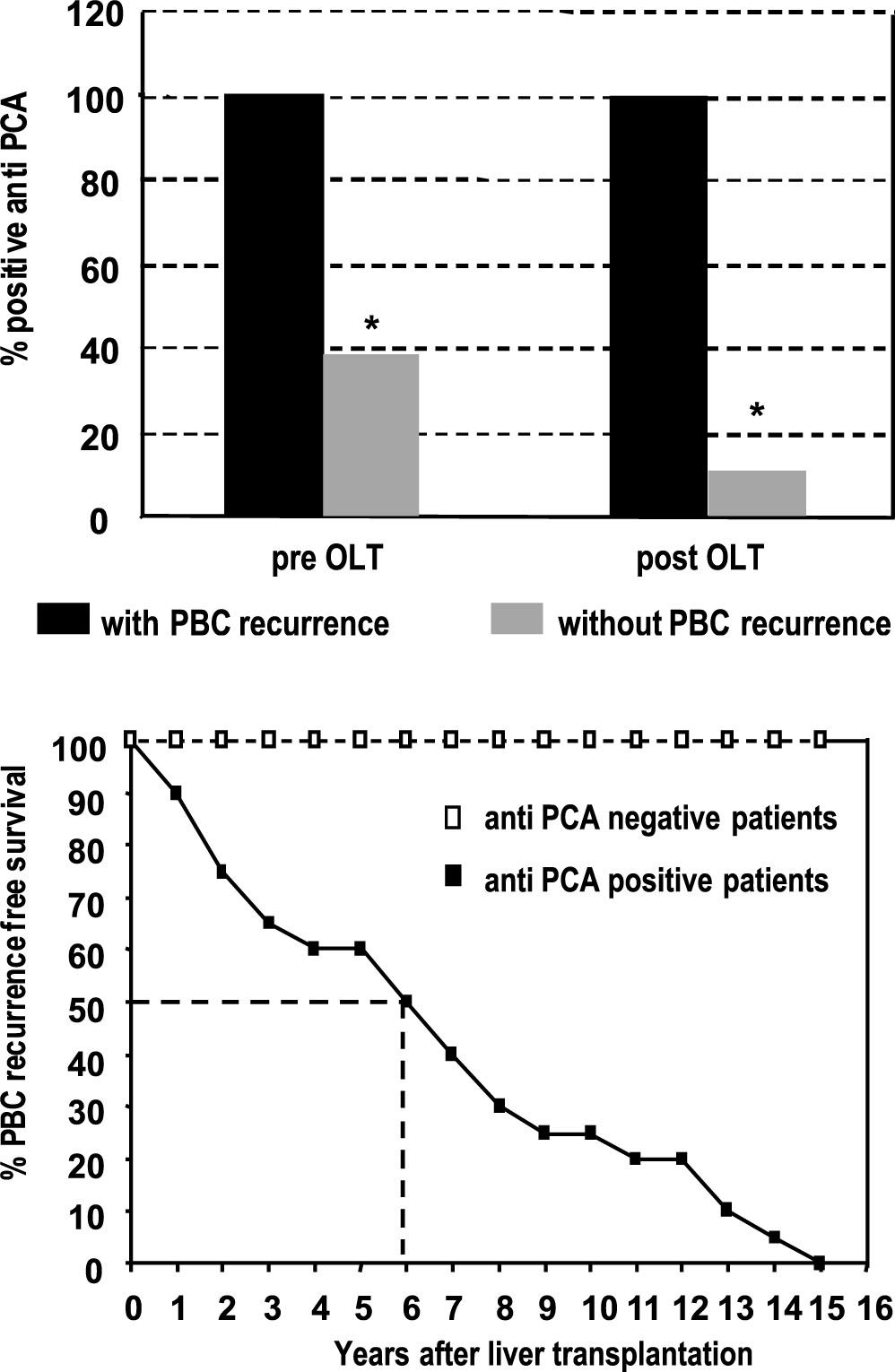

Recurrence of primary biliary cirrhosis after liver transplantationLiver biopsies were obtained in 34 patients post OLT upon clinical suspicion, and recurrent PBC diagnosed in 20/72 (28%) after a mean of 71 months (range 13-161) (Table 1B). Interestingly, anti-PCA were detected in 100% of patients with recurrence before and following transplantation (Figure 2). Furthermore 15 out of 28 patients with anti-PCA before OLT (54%) developed recurrence during follow-up.

Characteristics and antibody profile of 30 patients with recurrence of PBC post liver transplantation.

| Age (in years): 52 (range 25-63) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex: 19 female/4 male | ||

| Median follow up (in moths): 71 (13-161) | ||

| pre | post | |

| AMA positive | 18/20 (90%) | 16/20 (80%) |

| ANA positive | 5/20 (25%) | 6/20 (33%) |

| AntiPDHE2 positive | 9/18 (50%) | 8/16 (50%) |

| antiPCA positive | 20/20 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) |

| bilirubine (mg(dL | 8.6 (5-52) | 9.8 (5.6-33) |

| biopsy available | 20/20 (100%) | 20/20 (100%) |

| H. pylori positive | 8/20 (40%) | n.d |

A. Detection of αnti-PCA: Anti-PCA was significantly more frequent in patients with PBC recurrence after liver transplantation but also in those PBC patients that developed recurrence before OLT (* p < 0.01). B. Recurrence-free survival curves after liver transplantation for PCA positive and negative patients with PBC: While all patients with PCA develop PBC recurrence within 15 years after OLT, none of the PCA negative patients showed clinical signs of PBC recurrence.

51 patients (71%) received cyclosporine A and 21 patients (29%) tacrolimus as primary immunosu-ppressive agents. From the 20 patients with PBC recurrence after orthotopic liver transplantation, 12 patients had an immunosuppressive regime with ci-closporine (60%) and 8 patients received tacrolimus. There was no significant difference between initial immunosuppression of patients who developed PBC recurrence compared to the patients who did not develop PBC recurrence.

Incidence of Helicobacter pyloriTwenty-eight (38.8%) of the 72 patients were positive for H. pylori. The prevalence of H. pylori was not significantly different in the 20 patients, who suffered from PBC recurrence after OLT (40% H. pylori positive before OLT, Table 1A and B).

DiscussionAlthough overall survival in a long-term study with a follow-up of approximately II years of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis after OLT is very good (85.6%), recurrent PBC was diagnosed in 28% of all patients. These data are in line with several other studies, which described PBC recurrence after orthotopic liver transplantation in up to one-third of patients.7

To predict recurrent disease, a number of putative risk factors such as donor and recipient age, cold and warm ischaemic time, and tacrolimus-based immuno-suppression, have been reported.1 However, the diagnosis remains a challenge to transplant hepatologists. In this study cohort no difference between tacroli-mus-based immunosuppression compared to immuno-suppression with cyclosporine A was observed regarding the prevalence of recurrent PBC.

The analysis of the autoantibody profiles led to an interesting association not previously reported. Anti-PCA antibodies detected prior to transplantation were found to be significantly associated with PBC recurrence after OLT. While antimitochon-drial antibodies have a high specificity for PBC and serve as serological confirmation of the diagnosis,13 they did not have a predictive function for the recurrence of PBC in this study, which is in line with several other studies which demonstrate that AMA had no influence of PBC recurrence.11 Additional autoantibodies such as ANA and anti-PCA are detectable in a subgroup of PBC patients, but to date have limited diagnostic relevance other than in AMA-negative PBC, in which specific ANA exhibit a high specificity for the disease.14 Consistent with these findings, we did not observe any significant differences in the number of ANA, anti-PDH-E2 or anti-PCA positive patients before and after OLT. Although unspecific for the diagnosis of PBC, anti-PCA prevalence increased slightly after OLT, and was present in all patients who suffered from recurrent PBC. Recurrent PBC developed in 54% of patients with anti-PCA before OLT. This observation should be approved in a future prospective trial in order to find out if these autoantibodies may represent a simple and cost effective diagnostic marker for the likelihood of PBC recurrences after OLT. Importantly, we could not detect any correlation between disease recurrence after OLT and PCA antibodies in 14 patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH): out of 5 patients with AIH recurrence after OLT only one had detectable PCA antibodies (data not shown).

PCA have been primarily described in autoimmune atrophic gastritis and in atrophic gastritis following helicobacter infection. PCA autoantibodies have been associated with the severity of gastritis, gastric mucosa atrophy as well as with apoptosis of the mucosa of the gastric corpus.15,17 Human PCA sera react with recombinant H+, K+ ATPase.17 and may indicate an autoimmune reaction suggestive of the presence of H +,K+ ATPase specific T helper cells found in autoimmune gastritis[18]. From a clinical point of view PCA are classical markers associated with pernicious anemia and gastric atrophy. Since they have a high frequency of up to over 50% in H. pylori infected individuals an etiological link has been suggested.15,16,19 However, the role of H. pylori as a cause of autoimmune atrophic gastritis is controversially discussed.20 In many features atrophic gastritis after prolonged persistent H. pylori infection resembles autoimmune atrophic gastritis without H. pylori infection. In addition, PCA are detected in patients with atrophic gastritis and appear to correlate with disease activity and stage but are also detected in asymptomatic individuals with H. pylori infection. The relationship of PCA and PBC is unclear. T cell-mediated au-toreacitivity against transporter protein, which is also expressed in biliary epithelium may represent a link of these autoantibodies to PBC, which is primarily mediated by autoreactive T cells. In order to analyze the findings in respect to Helicobacter we evaluated, whether our cohort of PBC Helicobacter infection. None of the 72 patients had signs of atro-phic gastritis upon pre OLT gastroscopy. Interestingly, in this study, we also failed to detect significant differences of H. pylori prevalence between the PBC cohort with recurrence compared to all PBC patients after OLT, which is consistend with other studies.21 It is a diagnostically significant observation that PCA autoantibodies occurred in 41% of PBC patients before OLT and therefore appear to be associated with PBC, but in the group of recurrent PBC after OLT this marker was present in all patients.

Our data suggest that PCA autoantibodies, which are not specific for PBC, appear to indicate a higher probability of PBC recurrence after OLT. If PCA may really represent a facile marker of risk stratification, should be evaluated in future prospective studies.