Previous research has shown that consumers in developed countries display a high level of consumer ethnocentrism by prioritizing local products over foreign manufactured ones. Paradoxically, it is generally believed that consumers from developing countries, and least developed countries, are more inclined to buy imported goods instead of domestic ones.

This study examines the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism (C.E) and their willingness to purchase domestic products (W.B.D) in one developing country: Tunisia. To this end, this paper investigates the moderating effect of product country of origin (C.O.O) and conspicuous consumption (C.C) of a number of foreigners in knowingly developed and developing countries such as France, Italy, People's Republic of China and Turkey upon this relationship.

Based on a positivist epistemological approach, a questionnaire was developed and successfully administered based on a general sample of 152 individuals living mainly in the second biggest city of Tunisia, Sfax. Data was analyzed and tested by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) following the tow-step approach of Gerbing and Anderson (1988). The results of the analysis show that C.O.O and C.C moderate the intensity of the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and the inclination to buying domestic products.

Finally, this study both supports and adds to the existing literature that seeks to understand consumption behaviors in developing countries. It also shows that in developing countries, the relationship between C.E and the consumer's W.B.D is less evident than in developed countries.

With the constant flux of globalization, a noticeable increase in the movement of products across national boundaries can be observed (Makanyeza & du Toit, 2017; Ranjbarian, Morteza, & Mirzaei, 2010; Teo, Mohamad, & Ramayah, 2011).

However, this phenomenon has not only presented opportunities to marketers, but it has also created some challenges (Ranjbarian et al., 2010). In fact, openness on foreign markets introduces the consumers to products and services available throughout the world, given that they are increasingly exposed to products coming from different countries (Wong, Polonsky, & Garma, 2008). For this reason, marketers seek to understand which factors can affect the consumer's attitude toward the consumption of foreign products (Klein, Ettenson, & Morris, 1998; Wang & Chen, 2004).

Consumer ethnocentrism (CET) is one of the factors that can affect the consumer's decision of whether to buy domestic or foreign products. Precisely, it directly influences the consumer's willingness to purchase foreign products (Silili & Karunaratna, 2014). Consumer ethnocentrism “indicates a general proclivity of buyers to shun all imported products irrespective of price or quality considerations due to nationalistic reasons” (Shankarmahesh, 2006, p. 147). Studies generally show that there is a cause-effect relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and negative attitudes toward foreign products (Sharma, Shimp, & Shin, 1995). Consequently, the concept of ethnocentrism is distinctively important in international marketing, being a “potential handicap” for companies aiming to penetrate “overseas markets” (Altintas & Tokol, 2007, p. 309).

Overall, C.E is considered one of the powerful non-tariff barriers opposing to internationalism (Jeannet & Hennesy, 1995; Shankarmahesh, 2006).

Okechuku, (1994) and Good and Huddleston (1995) argue that consumer ethnocentrism is a pervasive phenomenon in highly industrialized countries. Studies conducted in developed countries usually show that ethnocentric consumers choose domestic products over foreign ones (Shimp and Sharma, 1987; Granzin & Painter, 2001; Suh & Kwon, 2002;Marín, 2005; Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2004). Nevertheless, certain ambiguity has been expressed regarding this relationship in some developing countries (Agbonifoh & Elimimian, 1999; Bahaee & Pisani, 2009; Hamin & Elliott, 2006; Samoui, 2009; Wang & Chen, 2004).

Although studies have been frequently conducted to investigate the importance of consumer ethnocentrism in developed countries, similar research is still lacking in developing ones (Makanyeza & du Toit, 2017; Pentz, Terblanche, & Boshoff, 2013; Rahman & Khan, 2012).

People in developing countries are becoming more preoccupied with the consumption of products, which has led to their marketplaces being “inundated” by a huge quantity of foreign goods. This raises questions over the consumers’ behavior in these parts of the world; how ethnocentrism affects their buying behavior and how they rank foreign products over nationally manufactured ones (Kamaruddin, Mokhlis, & Othman, 2002).

It is agreed upon that the product's country of origin is actually one of the most important indicators of product quality (Han, 1989; Klein et al., 1998). According to Wang and Chen (2004), research reveals that consumers in developed countries generally perceive domestic products as having a higher quality compared to imported ones (Damanpour, 1993; Dickerson, 1982; Elliott & Camoron, 1994; Morganosky & Lazarde, 1987), while the opposite applies for consumers in developing countries (Agbonifoh & Elimimian, 1999; Bahaee & Pisani, 2009; Batra, Venkatram, Alden, Steenkamp, & Ramachander, 2000; Wang & Chen, 2004; Wang, Chen, Chan, & Zheng, 2000). As a matter of fact, previous researches conducted in several developing countries demonstrate a common belief among consumers that foreign manufactured products are superior to those made by local producers. This widely-shared attitude among consumers of developing countries goes back to an equally-pervasive colonial mentality wherein consumers endorse the inferiority of their domestic products compared to foreign ones based on the economic strata of the developed countries (Wu, Zhu & Dai, 2010). Wang and Chen (2004) suggest the same. Given that consumers’ evaluation of the quality of products influences their purchase preferences, the impact of ethnocentrism on willingness to buy domestic or imported goods would, therefore, be different in developing and developed countries. Wang and Chen (2004) add that this gap is presumed to be more vocalized bearing in mind that in developing countries, consumers often regard foreign products as symbols of high social status and conspicuous consumption (Alden, Steenkamp, & Batra, 1999; Batra et al., 2000; Ger, Belk, & Lascu, 1993; Marcoux et al., 1997; Mason, 1981).

This paper attempts to provide more understanding of the effect of consumer ethnocentrism in one developing country, which is Tunisia.

2Literature review2.1Consumer ethnocentrism and buying intention of domestic products in developing country contextConsumer ethnocentrism is derived from the more general concept of ethnocentrism (Shimp, 1984). Ethnocentrism was originally introduced more than a century ago by William Graham Sumner in 1906. Generally, the concept of ethnocentrism “represents the universal proclivity for people to view their own group as the center of the universe, to interpret other social units from the perspective of their own group, and to reject persons who are culturally dissimilar while blindly accepting those who are culturally like themselves” (Shimp and Sharma, 1987, p. 280).

Ethnocentrism entered the field of marketing when it had been suggested to be one of the potential factors that can influence and forge consumer behavior (Javalgi, Khare, Gross, & Schere, 2005). It has been since considered as human disposition that can influence consumer choices in diverse purchasing situations (Boieji, Tuah, Alwie, & Maisarah, 2010). Shimp and Sharma (1987) were the first consumer scholars who applied the ethnocentrism concept in the study of marketing and consumer behavior and coined the term of “consumer ethnocentric tendencies” (CET) (Sharma et al., 1995).

Consumer ethnocentrism is defined as “the beliefs held by consumers about the appropriateness, indeed morality of purchasing foreign-made products” (Shimp & Sharma, 1987, p. 280). It is agreed that consumer ethnocentrism impacts negatively on consumers’ purchase intention toward foreign products. This implies that the high ethnocentric tendencies lead to unfavorable attitude toward purchasing imported products. According to Shimp and Sharma (1987) consumers refuse to buy foreign products because it is harmful to the national economy and can also be a direct or indirect cause for unemployment. Similarly, Wetzels, De Ruyter, and Van Birgelen (1998) reinforce the factor of allegiance to one's country, which leads the consumers to refuse buying foreign-made products. Thus, consumers exhibiting a strong sense of ethnocentrism are less, if not at all, interested in the consumption of foreign objects and services mainly due to a shared belief of the immorality of such a behavior and its harmful consequences on the local economy (Strizhakova, Coulter, & Price, 2008).

Generally, the level of ethnocentrism may vary from one consumer to another (Shimp, 1984; Durvasula, Andrews & Netemeyer, 1997; Vida & Fairhurst, 1999); from one region to another within the same country (Shimp & Sharma, 1987) and even from a whole country to another (Becic, 2017; Huddleston, Good, and Stoel, 2001; Lantz & Loeb, 1996).

Previous studies conducted in developed countries prove that ethnocentric consumers are more willing to buy domestic products instead of foreign ones (Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2004; Granzin & Painter, 2001; Marín, 2005; Shimp & Sharma, 1987;; Suh & Kwon, 2002). In contrast, it is generally believed that consumers from less developed and developing countries have a marked preference for imported goods over local ones (Agbonifoh & Elimimian, 1999; Batra et al., 2000; Papadopoulos, Heslop, & Bamossy, 1990; Ranjbarian et al., 2010; Wang & Chen, 2004). Thus, it is fair to say that findings about the effects of ethnocentrism in the developed countries do not apply in developing countries.

Wang and Chen (2004) argue that the observed relation between ethnocentrism and the willingness to buy domestic products is less evident in developing countries. For example, a cross-cultural comparative study conducted by Tsai, Lee, and Song (2013) shows that American consumers tend to be more ethnocentric than Chinese and South Korean consumers do.

Studies of Saffu and Walker (2006); Mensah, Bahhouth, and Ziemnowicz (2011) and Bamfo (2012) reveal that despite the sense of ethnocentrism shown by some respondents; Ghanaian consumers do not appear to be highly ethnocentric. The same has been reported for Iranian consumers (Bahaee & Pisani, 2009; Ranjbarian et al., 2010); Ethiopian consumers (Mangnale, Potluri, & Degufu, 2011); Nigerain consumers (Agbonifoh & Elimimian, 1999); Tunisian consumers (Samoui, 2009); Moroccan consumers (Hamelin, Ellouzi, & Canterbury, 2011) and Indonesian consumers (Purwanto, 2014). In Eastern Europe, Papadopoulos, Heslop, and Berács (1990) also concludes that the majority of Hungarians were either not or only slightly ethnocentric. For this reason, Agbonifoh and Elimimian (1999) suggest that in developing countries we cannot talk about ethnocentrism per say but we can rather find a sort of reverse ethnocentrism. In fact, reverse ethnocentrism is defined as “a type of ethnocentrism in which the home culture is regarded as inferior to a foreign culture” (Ferrante, 2008, p. 77). In market place, this leads to evaluating products coming from developed countries more positively than homemade products. Nevertheless, Hamin and Elliott (2006) unfold that the generalized preference for products originating from more advanced countries is not absolute and even in developing countries some consumers tend to select local products. In fact, a significant number of studies conducted in different developing countries challenge the widespread belief that consumer ethnocentrism is a phenomenon found only in developed nations. It also demonstrates that consumer ethnocentrism in those countries is not any less evident than it is found in other developed countries such as the US (Al Ganideh & Al Taee, 2012; Bandyopadhyay & Anwar, 2002; Bawa, 2004; Khan, Rizivi, & Qaddus, 2007; Nkoli, 2013; Rahman & Khan, 2012; Silili & Karunaratna, 2014; Upadhyay & Singh, 2006). Interestingly enough, Dogi (2015) puts forth the argument that consumers in developed countries should normally perform less ethnocentrically than those in developing countries do. The reason for this is that consumers in developed countries should not feel guilty for buying external instead of domestic products because their economy is dependable enough to support competition from foreign companies. In addition, supporting foreign products may urge local firms to reinforce their quality of production and enhance the market quality in general.

However, in developing countries consumers should be more concerned with the situation of their own economy because it is generally vulnerable in the face of foreign competition from the developed countries. Domestic consumption should, therefore, be more encouraged in developing rather than in developed countries. In this sense, it would be worth suggesting that, H1: In a developing country like Tunisia, there are some positive correlations between consumer ethnocentrism (C.E) and willingness to buy domestic products (W.B.D).

2.2Country of origin effect in the context of a developing countryThe value of global brands today is frequently affected by the image of their country of origin (C.O.O). Positive information about the origin of any brand may rend its promotion in foreign markets more successful. Thus, C.O.O information should have a significant impact on consumers’ evaluations of products from different countries. Indeed, it has long been evident that C.O.O affects product assessment and purchase decision as well (Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Han & Terpstra, 1988; Johansson, Douglas, & Nonaka, 1985).

The country associated with the product is thought to influence consumers’ quality judgments. Images of the manufacturing nation have a substantial impact on judgments of product quality (Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Hong & Wyer, 1989; Klein et al., 1998; Maheswaran, 1994; Papadopoulos & Heslop, 1993).

According to Hulland (1999, p. 26) several studies “found that consumers develop country stereotypes on the basis of the social and personal experiences (e.g., Papadopoulos, & Heslop, 1993; Samiee, 1994; Tse & Gorn, 1993), and that they prefer to buy their products from some countries over others”. For example, Japan has developed a strong reputation for designing and manufacturing superior consumer electronics products (Han & Terpstra, 1988; Ulgado & Lee, 1993). Therefore, products from more developed countries generally receive more positive evaluations from consumers than do products from less developed countries (Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Gaedeke, 1973; Klein, Ettenson, & Krishnan, 2006).

Equally important, previous studies have suggested a positive correlation between the evaluations of domestic products and a country's level of economic development (Gaedeke, 1973; Toyne & Walters, 1989; Wang & Lamb, 1983). According to Ramsaran (2015, p. 15) previous research studies have consistently showed that consumers from western Europe and north America prefer products originating from their home country over foreign ones (Bilkey & Nes, 1982; Reierson, 1967; Samiee, 1994; Verlegh, Jan-Benedict, & Steenkamp, 1997).

However, the situation is often reversed in developing countries (Agbonifoh & Elimimian, 1999; Batra et al., 2000; Ger et al., 1993; Li, Fu, & Murray, 1997; Marcoux et al., 1997; Opoku & Akorli, 2009; Sklair, 1994). In these countries, consumers typically perceive foreign products, especially those made in developed countries, as having a higher quality than domestic products (Wu, Zhu & Dai, 2010). According to Wang and Chen (2004) a product's country-of-origin often serves as a cue motivating consumer's ethnocentric tendency (Huddleston, Good, and Stoel, 2001). Nevertheless, sometimes it can also serve as a sign for demotivating a consumer's ethnocentric tendency like the case for most of developing and less developed countries. The empirical work of Yagci (2001) indicates that the effect of consumer ethnocentrism on the buying intention becomes more evident especially once consumers find themselves facing products manufactured in a less-developed nation. This means that the country of origin has a powerful effect even on the attitudes of highly ethnocentric consumers. Wang and Chen (2004) suggest that in the context of a developing country where people often underestimate the quality of their domestic products, a consumer with strong ethnocentric tendencies may evaluate products coming from developed countries as having a higher quality than domestic ones even though she or he considers buying non-domestic products as immoral behavior. Taking into consideration the general negative perception of domestic products, on the one hand, countered by the positive perception over foreign products, on the other hand, even ethnocentric consumers may feel sometimes confused over a locally produced product in a developing country context. To prove this, Wang and Chen (2004) take the Polish consumers as an example. In this former Eastern Bloc country, Supphellen and Rittenburg (2001) have found that when foreign products are significantly better than domestic ones, even ethnocentric consumers are “forced” to conform to the overall public opinion and eventually end up choosing those higher-quality foreign products over locally manufactured ones. Based on these premises, the second hypothesis will be the following. H2: In a developing country like Tunisia, C.O.O has an apparent impact on the relationship between C.E and W.B.D.

2.3Conspicuous consumption effect in a developing country contextConspicuous consumption (C.C) is defined as the purchase of expensive and luxury goods. The concept is widely associated with the American sociologist and economist Thorstein Veblen. Veblen was the first theoretician who coined the term in his most famous and seminal work “The Theory Of Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions” in 1899. In this theory, Veblen provides a behavioral explanation for conspicuous consumption by saying that “in order to gain and to hold the esteem of men it is not sufficient merely to possess wealth or power. The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence” (p. 26).

Veblen (1899) theorized that wealthy people choose to consume highly luxurious and expensive goods and services in order to display their material strength and gaining social elevation as a result. In this sense, extravagant consumption becomes a process of signaling personal wealth (Vijayakumar & Brezinova, 2012).

According to O’Cass and McEwen (2004), C.C is “the tendency for individuals to enhance their image, through overt consumption of possessions, which communicates status to others” (p. 34).

Remembering that CC is not limited to the leisure class; it can be displayed in any social or income group from the richest to the poorest (Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996; Basmann, Molina, & Slottje, 1988; Mason, 1981; Trigg, 2001; Veblen, 1899). According to Veblen, upon the influence of our emulation instinct people in either social class will always try to imitate the consumption lifestyle of those of the upper class, which means that even the poorest people are equally concerned with conspicuous consumption. Similarly, C.C does not merely pertain to people from rich countries rather it can largely involve consumers from developing and less developed countries. In fact, a theoretical study by Charoenrook and Thakor (1997) shows that conspicuous consumption is performed more extensively in economies with greater cross-sectional wealth disparities. This situation is often more described in developing countries than in developed ones. Economists believe that in times of economic transition values oriented for social position, conspicuous consumption and display of status become very pronounced (James, 1993). Usually, consumers in developing countries perceive foreign products as symbols of social status (Alden et al., 1999; Batra et al., 2000; Ger et al., 1993; Marcoux et al., 1997; Mason, 1981; Wang & Chen, 2004). In these countries, the word “imported” implies different symbolic meanings, such as good quality, fashion and high social status (Batra et al., 2000). For these reasons, in developing countries consumers concerned about their social status are always struggling to obtain those imported products despite their higher prices (Ger et al., 1993). According to Yang (1981) the psychology of people living in developing countries is often influenced by how others look at them. For example, Samoui (2009) uncovers that in Tunisia status brands are mostly foreign. Almost the same applies in some other developing countries like Romania and Turkey (Ger et al., 1993), Poland (Marcoux et al., 1997) and Mozambique (John & Brady, 2011).

Thus, we expect that in a developing country such as Tunisia, consumers perceive foreign products especially made in developed countries such as France or Italy as prestigious and luxurious products in comparison with the domestic ones. Previous studies conducted in different developing countries suggest that imported products especially those coming from famous developed countries are always seen as a distinguishing sign of an elevated social status (Batra et al., 2000; Chan, Cui, & Zhou, 2009; Nguyen and Tambyah, 2011; Wang & Chen, 2004; Zhou & Hui, 2003). Wang and Chen (2004) predict that in a developed country, CE and CC are positively correlated in most cases, given that either domestic or foreign products often offer the same positive values such as the favorable brand image and the high social status impression. Then in those countries, ethnocentric consumers will probably find many reasons to choose only local products. However, in a developing country, where foreign products are taken as a symbol of fashioned social superiority, C.C may weaken the influence of ethnocentrism on the purchase of domestic products. In a study conducted by Özer and Dovganiuc (2013) in Turkey results show that C.C, which is generally associated with the purchase of foreign products, mitigates the negative effect of consumer ethnocentrism on the purchasing intention of foreign brands. The study also reveals that even ethnocentric Turkish consumers tend to display their wealth by purchasing foreign brands despite their belief in the immorality of this conduct. This means that in developing countries, even consumers holding high ethnocentric values are prone to buying foreign products if they wish to satisfy their prestigious needs. Therefore, it could be assumed that, H3: In a developing country like Tunisia, C.C affects the relationship between C.E and W.B.D.

2.4Research contextRegarding C.C effect, apart from their functional attributes (warmth or protection), clothes have many social and psychological effects in a person's life particularly on his/her own identity expression. Clothes “say(s) how important an individual is, tells others how much status an individual has, what the individual is like” (O’Cass, 2000, p. 547; Roach-Higgins & Eicher, 1992; Twigg, 2009). Still on the C.O.O effect subject, since the Tunisian government has already reduced tariff as well as non-tariff barriers in all industries and the growing up of the underground trade (following the 2011 uprising), domestic manufacturers are facing extreme competition from Asian and European imports. This is made worse by a rising demand for foreign-made clothes especially with a large quantity of Asian and European imports competing with domestic brands. Thus, with Asian and European clothing products invading the Tunisian market, the latter is becoming highly competitive.

Accordingly, this study resorts to clothes as a market product for investigating the effects of ethnocentrism. Turning the focus to foreign brands, despite the lack of accurate information on the Tunisian importation of clothes (“prêt à porter”) (mainly due to the rising of the underground economy and counterfeit), the main suppliers of clothes (“prêt à porter”) for Tunisia are Turkey, People's Republic of China, Italy, France and Spain… It should be borne in mind also that European countries like France, Italy and Germany provide a primary source of Tunisia's second-hand-market products.

As we have already shown that the value a product is measured by the development rate of its country of origin, in this research four different countries have been chosen for examination based on their general level of development. French and Italy are commonly known to be developed countries (they have a very high HDI for example); whether in Tunisia or elsewhere. However China and Turkey are generally classified as developing countries (although they are prospering both economically and technologically, these countries still suffering basic problems in some issues which deprives them from being considered as developed countries). In addition, as it has been shown already, Tunisian consumers are used to meet the “made in” Italy, Turkey, France and China brands when they go clothes shopping. On this account, these four countries have been chosen in this study as C.O.O and C.C effect of foreign products.

3Research methodology3.1Sampling and data collectionTo attain the aims of this study, a questionnaire was developed and delivered to nearly 250 Tunisian citizens. Most of them live in the city of Sfax in the south of Tunisia.

Sfax is the second major city in Tunisia after the capital Tunis with nearly 1/4 million inhabitants in 2012. Despite its conservative tendencies, this coastal city is greatly influenced by western lifestyle due its heavy connection with many European cities especially in the business and educational sectors.

In this study, a total sample of 250 consumers was randomly selected. People from different ages, social and educational levels participated in the survey, as shown in Appendix 1 (supplementary materials).

In this study, a total sample of 250 consumers was randomly selected. People from different ages, social and educational levels participated in the survey, as shown in Appendix 1 (supplementary materials).

At the end, a number of 152 usable and completed auto-administrated questionnaires have been collected; response rate was 60, 8%.

3.2MeasuresA questionnaire consisting of five different sections has been used to gather empirical data in this study.

The first section of the questionnaire includes questions to measure consumer ethnocentrism by the popular CETSCALE developed by Shimp and Sharma (1987) in a short form already suggested and used by Shimp and Sharma (1987) themselves, Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998), Lindquist, Vida, Plank, & Fairhurst (2001), and Douglas and Nijssen (2003) (Bawa, 2004).

Questions about the perceptions of Tunisian consumers regarding the country of origin were asked in the second section of the questionnaire. The purpose of this section is to evaluate the Tunisian consumer's general attitude toward Italy, France, Turkey and China as countries. For this reason, an adapted form of the Pisharodi and Parameswaran's (1992) image of country of origin measurement scale has been selected.

The scale consists of 24 items (after adjustment) divided according to three major features; the GCA (general country attribute), the GPA (general product attributes) and the SPA (specific product attributes). According to Dinnie (2004, p. 176) “Parameswaran and Pisharodi believe that attributes contributing to any particular (C.O.O) image may differ across countries and therefore there exists a potential weakness in the use of standardized country of origin image scales to measure country of origin images of products originating in diverse countries”. Nevertheless, given that this scale has been originally developed to measure the specific attributes of cars and not clothes, an exploratory small study (focus group) has been established to uncover the specific attributes of clothes and three new items have been included.

The third section of the questionnaire includes questions to assess conspicuous consumption tendencies of Tunisian consumers. The scale of Marcoux et al. (1997) has been used for this. This 18 items scale has five different components and has been allocated to estimate conspicuousness trends in different contexts especially in devolving countries (Poland, China, Iran, and Turkey). All variables in the latter three sections were measured by 5-point scales ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

In the fourth section of questionnaire, buying intentions for domestic clothes were measured by the purchase probability scale adopted from Juster (1966), also with 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all likely, 5=very likely). Consumers were asked how likely would they want to buy notionally produced clothes if they find that their price and quality are quite acceptable.

Finally, the last section of the questionnaire consists of demographic and socio-economic questions. Noteworthy, before being applied in the final survey, all these measures were first pretested on about 50 people. Questionnaires were delivered in French language after vocabulary verification and revision.

4Data analysis and hypotheses testingFour models in this paper (Italian, French, Turkish and Chinese) have been tested by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), following the two-step approach of Gerbing and Anderson (1988). The first part in this approach consists of conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for all variables presented in the model to improve its construct validity, and then, in the second part, to test the structural relationships (hypotheses testing) existing in it (Roussel, Durrieu, Campoy, & Akremi, 2002). However, and as our model presents two moderating effects to be tested, the three steps of Ping (1995) MSEM approach for models with one indicator dependent variable has been used for this, as described by Cortina, Chen, and Dunlap (2001) and El Akremi (2005) and applied by Conway, Fu, Monks, Alfes, and Bailey (2015). Then Ping (1995) and Gerbing and Anderson (1988) approaches were taken together following El Akremi (2005) outlines (see figure in Appendix 2).

Four models in this paper (Italian, French, Turkish and Chinese) have been tested by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), following the two-step approach of Gerbing and Anderson (1988). The first part in this approach consists of conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for all variables presented in the model to improve its construct validity, and then, in the second part, to test the structural relationships (hypotheses testing) existing in it (Roussel, Durrieu, Campoy, & Akremi, 2002). However, and as our model presents two moderating effects to be tested, the three steps of Ping (1995) MSEM approach for models with one indicator dependent variable has been used for this, as described by Cortina, Chen, and Dunlap (2001) and El Akremi (2005) and applied by Conway, Fu, Monks, Alfes, and Bailey (2015). Then Ping (1995) and Gerbing and Anderson (1988) approaches were taken together following El Akremi (2005) outlines (see figure in Appendix 2).

4.1Reliability and validity testBefore proceeding to testing hypotheses in our four models, reliability measurement has been checked using Cronbach alpha. An exploratory then a CFA processes have been conducted consecutively to reduce data to necessary and to examinate the similarity and respectively the difference between all measures following Fornell and Larcker (1981) recommendations. To assess models suitability, we used the overall model chi-square (χ2)/df, the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI, Tucker & Lewis, 1973), the comparative fit index and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, Brown & Cudeck, 1993).

As shown in Table 1, all measures are seen to be reliable as the Cronbach alpha exceeds the 0.7 in all variables presented in the four models. Similarly, the Ave (Average Variance Extracted) has values greater than 0.5 in any single construct composing models; it means that convergent validity is confirmed in all of them (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Discriminate validity was tested by calculating the squared correlation r2 between constructs in every single model and comparing them with their respective Ave value. Aves should be always greater than their respective squared correlations to prove constructs uniqueness.

Measurements reliability and validity.

| Country-Model | Variables | Items | α Cronbach | Ave | r2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All four | C.E | 8 | 0.822 | 0.773 | C.E↔C.O.O | C.E↔C.C | C.C↔C.O.O |

| Chinese model | C.O.O | 11 | 0.826 | 0.651 | 0.0003 | 0.005 | 0.337 |

| C.C | 18 | 0.925 | 0.583 | ||||

| Turkish Model | C.O.O | 14 | 0.857 | 0.665 | 0.005 | 0.028 | 0.214 |

| C.C | 17 | 0.922 | 0.573 | ||||

| Italian Model | C.O.O | 7 | 0.779 | ≈0.5 (0.494) | 0.000 | 0.091 | 0.094 |

| C.C | 16 | 0.903 | 0.559 | ||||

| French Model | C.O.O | 9 | 0.830 | 0.541 | 0.002 | 0.0029 | 0.131 |

| C.C | 14 | 0.863 | 0.588 | ||||

Both Ave and r2 values are obtained after conducting a CFA and while enhancing quality adjustment of our measurement models fowling the Gerbing and Anderson (1988) tow step approach.

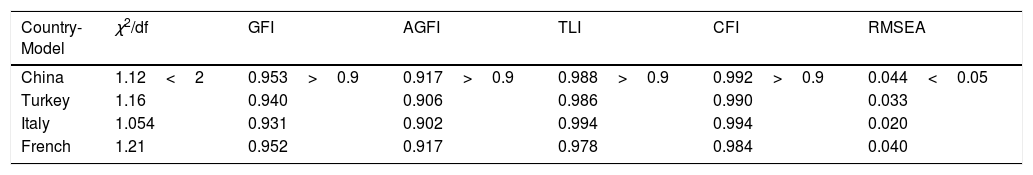

Finally, CFA shows a valid fit level for all the four Country-Models. The RMSEA, CFI and GFI fitness indices are within the rule of thumb criteria. All the values obtained from this study were within the range of acceptable fitness values as shows the next table (Table 2).

Fitness assessment of the measurement models of the four countries.

| Country-Model | χ2/df | GFI | AGFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 1.12<2 | 0.953>0.9 | 0.917>0.9 | 0.988>0.9 | 0.992>0.9 | 0.044<0.05 |

| Turkey | 1.16 | 0.940 | 0.906 | 0.986 | 0.990 | 0.033 |

| Italy | 1.054 | 0.931 | 0.902 | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.020 |

| French | 1.21 | 0.952 | 0.917 | 0.978 | 0.984 | 0.040 |

The MSEM Ping (1995) approach was used for testing resulting research hypotheses in all the four Country-Models as described above. The application of the MSEM Ping (1995) approach consisted first in standardizing all indicators for the independent variable X (consumer ethnocentrism, C.E) and moderators Z (country of origin, C.O.O and conspicuous consumption, C.C).

Then, in creating interaction term between X and Z variables XZ=∑X×∑Z, and fixing the measurement properties for interaction term XZ, λXZ and θXZ as follows:

Finally, it was employed in estimating the model with the interaction term and evaluating the moderating effect as well as the other structural paths.

- •

Turkish Model hypotheses testing;

- •

Italian Model hypotheses testing;

- •

Chinese Model hypotheses testing;

- •

French Model hypotheses testing.

Our data analysis shows that C.E affects positively the willingness or the buying intention of domestic product of the Tunisian consumer (W.B.D) whatever is the country representing the model (Tables 3–6).

Descriptive statistics point out that countries like France or Italy have a positive country of origin image in the mind of Tunisians, as their mean scores (MS) reveal respectively two values significantly above the average of 3 (4.039 and 3.94). However, a country like China shows only a value of 2.62<3. Hence, regarding the level of education, standards of living, quality of products or skilled work force, Tunisians rank France as the best country, followed by Italy, Turkey and finally China. This means that Tunisians do not regard China with dilated pupil's eyes. Similarly, when it comes to prestige and social status values, Tunisians rank Italy as the first popular country with MS=3.94, then French (MS=3.70) then Turkey (MS=2.48) and finally China with MS=1.91, significantly below the average of 3. This means that even if Tunisians are used to buying Chinese clothes; they do not buy them for social status motivations. Concerning now the moderating effects of C.O.O and C.C on the relationship between C.E and W.B.D, results inform that C.C moderates negatively the relationship between C.E and W.B.D, except in the case of the Italian model (β=−0.235, p<0.01), the country with the highest luxury product image in the study (Table 4).

This leads to think that in Tunisia even individuals with high ethnocentric orientations may hesitate before choosing the domestic product if the find available a similar one imported from another country with high C.C image such is Italy. Similarly, it was found that C.O.O moderates the relationship between the C.E and W.B.D in two opposite ways.

First, C.O.O moderates positively the relationship between the C.E and W.B.D in the Chinese model (β=0.194, p<0.05), the country with the lowest country of origin image in this study (Table 5). However, it moderates negatively the relationship between the C.E and W.B.D in the French model (β=−0.161, p<0.05), the country which holds the favorite country of origin's image in this study (Table 6).

This means that in Tunisia even individuals with weak ethnocentric tendencies may find themselves behaving in a higher ethnocentric manner than usual if they are bound to choose between two similar products, one coming from a country with unfavorable C.C image (such as China) and another one domestically manufactured.

Equal to the case for countries with positive C.C image such as Italy, results indicate that in Tunisia even people with high ethnocentric values may sometimes ignore their ethnocentric inclinations in the face of products with high C.O.O image such as French for example.

Previous studies conducted in developed countries demonstrate that ethnocentric consumers are more willing to buy domestic products instead of foreign ones (Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2004; Granzin & Painter, 2001; Marín, 2005; Shimp & Sharma, 1987; Suh & Kwon, 2002). Yet, many scholars believe that conclusions about consumer ethnocentrism effects in developed countries risk being different in developing countries. For example, Agbonifoh and Elimimian (1999) suggest that in developing countries we cannot talk about consumer ethnocentrism rather than a reverse ethnocentrism. This means that ethnocentrism in developing countries has only a minor impact or even reversed (negative) impact on the proclivity of buying domestic products.

In fact, many empirical studies show that those countries have considerably a low level of consumer ethnocentrism (Bahaee & Pisani, 2009; Bamfo, 2012; Cazacu, 2016; Hamelin et al., 2011; Mangnale et al., 2011). In this paper, it was found that although Tunisian people are not highly ethnocentric consumers (MS=2.84 so below the average of 3), their ethnocentrism always affects positively their buying intention of domestic products whatever the case. It means that even in a developing country like Tunisia we can expect an eventual effect of consumer ethnocentrism on buying behaviors. Nevertheless, it was also found that consumer ethnocentrism influences attitudes toward foreign clothes and that willingness to buy domestic clothes vary by country of origin. Negative impressions of Tunisian consumers on products originating from some foreign countries such as China can increase their tendency to buy domestic products, but if they hold a foreign country in high esteem such as France or Italy, their willingness to buy local products lessens even among the most ethnocentric consumers. Otherwise, in Tunisia as a developing country, the relationship between consumer ethnocentrism and willingness to buy domestic products depends on the consumers’ perception of C.O.O and C.C of the import country. Countries with extremely C.O.O and C.C valuable image can significantly alter the strength of this relationship whether positively or negatively, sign of vulnerable level of consumer ethnocentrism. Similar results have been found in other developing countries such as Iran (Ranjbarian et al., 2010) and China (Wang & Chen, 2004).

6ConclusionThe results of this paper may contribute to the literature on predicting and explaining consumer attitudes and behavioral intentions to buy foreign versus domestic products in developing countries. Products and services coming from developed countries could not fear non-tariff barriers such as consumer ethnocentrism when penetrating developing countries markets. However, products and services coming from developing countries should target only non-ethnocentric consumers when trying to enter markets of other developing countries. Trying to improve product quality or applying low prices strategies, rendering the prices significantly much lower than those of domestic competitors, may represent suitable solutions for developing countries seeking to export, especially that consumers in other developing countries generally have a low purchasing power. Local and domestic producers in developing countries should not overestimate the effect of consumer ethnocentrism because people in developing countries have generally a low level of consumer ethnocentrism.

Local companies in Tunisia should take the responsibility to improve the quality of their products and to increase the effectiveness of their marketing practices. Furthermore, they may seek to joint venturing with some foreign brands with favorable country of origin image such as Italian or French ones and overcome the ethnocentric inefficiency of local consumers.

Governments in developing countries should engage in a huge advertising campaign promoting domestic products, like what happened in Tunisia during the end of the 90s. Tunisian authorities ought to invest in the cultivation of patriotic feelings following the 2011 revolution and convince citizens to buy nationally manufactured products.

Limitations on this research mainly concern the sample size, which is composed only by 152 individuals; it seems to be relatively limited to reach full generalization. Moreover, 92% of them live in just one city; Sfax. Studies on consumer ethnocentrism show that the level of ethnocentrism may change from one location to another even within the same country. For example, we expect that in Tunisia consumers living in internal areas have generally more ethnocentric tendencies than consumers living in the north or in some coastal areas due to social and cultural reasons.

Future studies of consumer ethnocentrism in Tunisia should use larger sample size with people selected from different geographical zones. In addition, and with regard to factors moderating the relationship between C.E and W.B.D in developing countries, psychosocial factors like religious tendencies have been proved to enhance ethnocentric values or lead to more willingness to purchase domestic products over foreign ones (Haque et al., 2015; Matić, 2013). Actually, religiosity is remarkably rising especially in the so-called Arab spring countries like Tunisia. So, could religious affiliations mitigate the potential effect of high C.O.O and C.C products upon the relationship between C.E and W.B.D in Arab spring countries?