Research into the internationalisation strategies of family businesses is plagued by the excessive use of many and varied concepts to define these companies, and often leads to diverse and disparate results. The conceptual spectrum used by researchers is very broad, ranging from the simplest definition, in which a company is classified as a family business on the basis of the perception of its owners and/or managers, to others which consider variables such as ownership, management, involvement of the family in the business, continuity and combinations thereof. The results obtained highlight the need for those researching family business internationalisation strategies to use a standard definition of family business, so enabling us to continue advancing in our knowledge of this topic and avoid coming to different conclusions merely as a result of having based our research on different definitions.

One family business (FB) research line stems from the need to adopt a single general criterion to conceptualise such enterprises. This would ensure that the concept used in the different studies of these companies does not condition the results obtained.

Related to the foregoing, research conducted on the internationalisation strategies of such companies (Kontinen & Ojala, 2010a) also shows that excessive use is made of multiple and varied concepts of FB, often resulting in disparate and diverse results (Arregle, Naldi, Nordqvist, & Hitt, 2012). The conceptual spectrum used is extremely broad, ranging from the simplest conceptualisation based on the owners and/or managers’ perception of the family or non-family nature of the business to other concepts that employ variables such as ownership, management, commitment or continuity and combinations thereof. Thus, when studying the internationalisation strategies of family firms there is a need to make more coherent use of definitions of FB or to enhance the concept to be able to describe different types of family businesses (Kontinen & Ojala, 2010a).

The research objective of the current study is to examine whether the concept of FB researchers use influences the company's international commitment (IC) once it has opted to embark on international development (ID) compared to that of non-family businesses (NFBs).

Following on from this introduction, this paper includes a literature review on the concept of FB employed in studies that analyse the internationalisation strategies of these companies. This is followed by a description of the empirical study and the results obtained. The final section presents the main conclusions and the academic and managerial implications.

2Diversity of FB concepts in the study of international strategyFamily businesses are among the most important contributors to the creation of wealth and employment in economies all over the world, and they range from small enterprises serving the neighbourhood to large conglomerates that operate in multiple industries and countries (Ramadani & Hoy, 2015). Thus, defining the FB is a complex issue because its key components represent the interaction of the family and business systems (Chua, Chrisman, & Sharma, 1999), to which some researchers add ownership (Lansberg, Perrow, & Rogolsky, 1988; Donckels & Lambrecht, 1999). Others consider the individuals system as a key element of this interaction (Habbershon & Williams, 1999; Habbershon, Williams, & McMillan, 2003; Klein & Kellermanns, 2008). However, none of the definitions of FB from the literature has been broadly accepted (Sharma, 2004), and authors such as Brockhaus (1994) and Littunen and Hyrsky (2000) claim that there is no broadly accepted definition of FB. This argument is supported by Astrachan, Klein, and Smyrnios (2002) and Chua et al. (1999), and is surprising bearing in mind that the study of family businesses as an independent academic discipline dates from the 1990s (Bird, Welsch, Astrachan, & Pistrui, 2002).

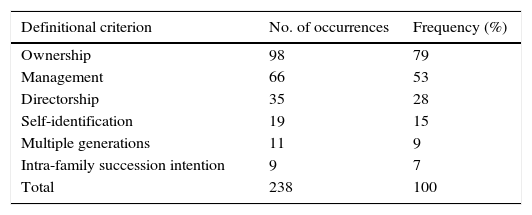

This lack of unanimity about the definition of FB makes it difficult to compare studies (Ramadani & Hoy, 2015) and to determine the boundaries of the field of FB research (Hoy & Verser, 1994). Ramadani and Hoy (2015) identify the criteria most often used to define family businesses (see Table 1).

Criteria used to define family businesses.

| Definitional criterion | No. of occurrences | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | 98 | 79 |

| Management | 66 | 53 |

| Directorship | 35 | 28 |

| Self-identification | 19 | 15 |

| Multiple generations | 11 | 9 |

| Intra-family succession intention | 9 | 7 |

| Total | 238 | 100 |

Source: Ramadani and Hoy (2015)

Some additional information should be pointed out about the above table. First, several authors combine some of the criteria cited to define FBs, which makes the percentages sum to more than 100% (Ramadani & Hoy, 2015). Second, these authors do not consider the involvement criterion, which Zahra (2003) sees as unique to family businesses. Involvement not only gives family members the information to commit to a course of internationalisation but also the knowledge to evaluate the merits and outcomes of this strategy. And third, a number of criteria–multiple generations, intra-family succession intention and the existence of family members being trained to take up a job in the business in a short period of time–can be integrated into a single criterion called continuity (Vallejo, 2005).

On the other hand, focusing on the FB internationalisation strategy literature, Kontinen and Ojala (2010a) pinpoint among the variables most frequently used to conceptualise this type of firm the combination of ownership and management, coinciding with Gallo and Sveen's (1991) findings. Other studies add the desire for continuity or the owners or managers’ subjective perception of the family or non-family nature of the business. Kontinen and Ojala (2010a) continue by explaining how some research papers do not present any concept of FB, and stress the need to improve and unify the definition of FB to make research on the international strategies of these companies easier both to understand and compare.

Studies examining the international strategies of FBs have most often used, either individually or in various combinations thereof, the following criteria to define this type of firm: the self-perception of the company as a family or non-family business; the company's ownership by members of the same family; management by persons with family ties; generational change or desire for continuity of the company through successive family generations; and the commitment and involvement of family members in the business.

Thus, following the literature reviews by Kontinen and Ojala (2010a) and Arregle et al. (2012), Table 2 (abridged version)1 shows how multiple and varied concepts of FBs have been used in the study of their international strategy (IS) and, depending on the definition used, how the research findings vary considerably, even to the point of becoming contradictory. For instance, whereas Zahra (2003) finds that family ownership and involvement support internationalisation because family members act as good stewards of their existing resources, Fernández and Nieto (2006) show that resources provided by corporate, non-family owners spur export behaviour in family firms, while the resources of family owners have the opposite effect. Gómez-Mejia et al. (2010) also find that FBs exhibit lower levels of internationalisation to avoid loss of their socio-emotional wealth. And Sciascia, Mazzola, Astrachan, and Pieper (2012) find an inverted U-shaped relation between family ownership and international intensity. All these various research studies were conducted on the basis of different definitions of FBs (see Table 2).

Literature review of FB concepts in studies on FBs’ international strategy (1999–2016).

| Authors | Title | Methods | Findings | Family business concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uni-dimensional definitions | ||||

| Self-perception | ||||

| Okoroafo (1999) | Internationalisation of Family Business: Evidence from Northwest Ohio, USA | Empirical Survey | If a family business does not get involved in foreign markets in the first and second generations, it is unlikely to do so in later generations. Also, approximately half of family businesses sold their products in foreign market via exporting and joint ventures. | Family business is one which its owner identifies as a family business. |

| Zahra (2005) | Entrepreneurial Risk Taking in Family Firms | Empirical Survey | Family ownership and involvement promote entrepreneurship, whereas the long tenure of CEOs/founders has the opposite effect. | Family firm is what the company's CEO or highest senior executive classifies as family business. |

| Okoroafo and Koh (2010) | Family Businesses’ Views on Internationalisation: Do They Differ by Generation? | Empirical Survey | First, second and third generation owners have similar views on internationalisation. | Family business is one which its owner identifies as a family business. |

| Okoroafo and Perry (2010) | Generational Perspectives of the Export Behaviour of Family Businesses | Empirical Survey. | The second family generation is more motivated to become international, and it has the support of a higher propensity to use public institutions. Also, differences exist in the use of intermediaries for export activities depending on the family generation analysed. | Family business is one which its owner identifies as a family business. |

| Fuentes-Lombardo et al. (2011) | Intangible assets in the internationalisation of Spanish wineries: Directive and compared perception between family and non family businesses | Empirical Survey. | Intangible resource endowment in Spanish wineries varies between family and non-family businesses. | Family business is one which its owner identifies as a family business. |

| CONSTRUCT DESIGNED: “FBC1” COMPANIES ARE CLASSIFIED AS FAMILY BUSINESSES IF THEIR CEOS PERCEIVE THEM TO BE FAMILY BUSINESSES | ||||

| HYPOTHESIS TO BE TESTED: H1a. There is no difference in the ID between FBC1 family businesses and non-family businesses. H1b. There is no difference in the IC between FBC1 family businesses and non-family businesses. | ||||

| Ownership | ||||

| Tsang (2001) | Internationalising the Family Firm | Empirical Case Study | Learning by doing gives a competitive advantage to these firms in this internationalisation strategy, via diversification. | A Chinese family firm is one where one of the partners and his/her family have most of business ownership. |

| Arregle et al. (2012) | Internationalisation of Family-Controlled Firms: A Study of the Effects of External Involvement in Governance | Empirical Survey | The presence of non-family members on the board of directors (BOD) provides family businesses with the necessary resources to support their international strategies. | A family firm is one in which ownership by persons outside the family does not exceed 49%. |

| Colli et al. (2013) | Family character and international entrepreneurship: A historical comparison of Italian and Spanish ‘new multinationals’ | Empirical Case Studies | Family character favours international expansion in at least three ways: (1) by granting more freedom to the managers of the company to develop their business model; (2) by facilitating the transfer and exploitation of this model in foreign markets; and (3) by making the adoption of governance structures based on trust easier. | Family businesses are companies in which the founder or a member of the family is the company director or owns more than 5% of the firm's equity. |

| Calabrò et al. (2016) | Governance structure and internationalisation of family-controlled firms: The mediating role of international entrepreneurial orientation | Empirical PLS-method | A high involvement of non-family members in the governance structure has a positive impact on family firms’ pace of internationalisation, and this relation is mediated by the firm's international entrepreneurial orientation. | A family business is one in which at least 50.1% is owned by one family. |

| CONSTRUCT DESIGNED: “FBC2” COMPANIES ARE CLASSIFIED AS FAMILY BUSINESSES IF OWNERSHIP BY PERSONS OUTSIDE THE FAMILY DOES NOT EXCEED 49% | ||||

| HYPOTHESIS TO BE TESTED: H2a. There is a difference in the ID between FBC2 family businesses and non-family businesses. H2b. There is a difference in the IC between FBC2 family businesses and non-family businesses. | ||||

| Family involvement in business | ||||

| Cerrato and Piva (2012) | The internationalisation of small and medium-sized enterprises: the effect of family management, human capital and foreign ownership | Empirical Probit method. | The lack of human resources is the main limiting factor of FBs’ growth in international markets. The management nature (family vs. non-family) comes from the family involvement in business and it influences the decision to become international. However, once the internationalisation strategy is deployed, the level of internationalisation does not significantly depend on the composition of the top management team (TMT). | Family management is a continuous variable measuring a greater or lesser involvement of the business-owning family. |

| Mitter et al. (2014) | Internationalisation of family firms: the effect of ownership and governance | Empirical Standardised online questionnaire | The relation between family influence and internationalisation is inverse U-shaped. When family influence on ownership, management, and governance boards is relatively high (high SFI), firms tend to stay local. FBs with a medium SFI are more internationally diversified than NFBs. Not only family ownership but also family influence on governance in general has a non-linear impact on internationalisation. | Applying the F-PEC Scale, an FB is a firm with a Substantial Family Influence (SFI) indicator higher than 1. |

| Bi-dimensional definitions | ||||

| Self-perception and ownership | ||||

| Westhead and Howorth (2006) | Ownership and Management Issues Associated With Family Firms Performance and Company Objectives | Empirical Survey | Firms with CEOs drawn from the dominant family group owning the business are less likely to be exporters. | A Family Firm is a firm identified as such by the CEO, the general director or the chairman and where more than 50% of the company is under controlling group whose members are blood or marriage relatives. |

| Self-perception and management | ||||

| Davis and Haverston (2000) | Internationalisation and Organisational Growth: The Impact of Internet Usage and Technology Involvement Among Entrepreneur-led Family Businesses | Empirical Survey | Among entrepreneur-led family businesses, internationalisation and growth are positively affected by increased use of Internet and increased investments in information technology. | A family firm has the entrepreneur-founder or a family member as president or CEO, employs members of the entrepreneur-founder's family and has managers defining their firm as a family business. |

| Self-perception and control | ||||

| Piva et al. (2013) | Family Firms and internationalisation: An exploratory study on high-tech entrepreneurial ventures | Empirical Online Survey | FBs in technology-intensive sectors have a greater chance of continuing their internationalisation strategies than non-family businesses. | Family business is one where its owner identifies it in this way and where at least 50% of the company is under the control of a minimum of 2 members of the same family. |

| Self-perception & family involvement | ||||

| Fernández-Olmos, Gargallo-Castel, & Giner-Bagües (2016) | Internationalisation and performance in Spanish family SMES: The W-curve | Empirical Panel Data Analysis. | The family dimension moderates the relation between internationalisation and firm performance, and strong support for the hypothesis that a W-curve stage approach better describes the internationalisation performance relation in FBs. | FBs are firms where they self-classify themselves as a family business based on the involvement of a family group in the control. |

| Ownership & Continuity | ||||

| Zahra (2003) | International expansion of U.S. manufacturing family businesses: the effect of ownership and involvement | Empirical Survey | Ownership is a significant variable that determines the degree and geographic scope of internationalisation, supporting the Stewardship theory rather than the Agency Theory because of altruism. | Family firms are those businesses that report some identifiable ownership share by at least one family and have multiple generations in leadership positions. |

| Casillas et al. (2010) | Configurational Approach of the Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Growth of Family Firms | Empirical Survey | The results show that (a) entrepreneurial orientation positively influences growth only in second-generation family businesses; (b) the moderating influence of the generational involvement is related to the risk-taking dimension; and (c) dynamism and hostility of the environment, respectively, moderate the relation between entrepreneurial orientation and growth in a positive sense. | Although the authors do not explicitly define FBs, the FBs in the sample are those in which one family exercises ownership control and they have undergone a succession process, i.e., they should be in at least their second generation. |

| CONSTRUCT DESIGNED: “FBC3” COMPANIES ARE CLASSIFIED AS FAMILY BUSINESSES IF THEY REPORT SOME IDENTIFIABLE OWNERSHIP SHARE BY AT LEAST ONE FAMILY AND THEY HAVE UNDERGONE A SUCCESSION PROCESS | ||||

| HYPOTHESIS TO BE TESTED: H3a. There is a difference in the ID between FBC3 family businesses and non-family businesses. H3b. There is a difference in the IC between FBC3 family businesses and non-family businesses. | ||||

| Ownership & management | ||||

| Tsang (2002) | Learning from overseas venturing experience. The case of Chinese family businesses | Empirical. Case Study. | Features of Chinese FBs (authority and control centrality) allow firms to concentrate strategic knowledge in the boss and his family. Non-family members also learn, though not at the strategic level, through their involvement in daily operations. | An FB is a firm where a family owns the majority of stock and exercises full managerial control. |

| Graves and Thomas (2004) | Internationalisation of the family business: a longitudinal perspective | Empirical Business Longitudinal Survey (BLS) & case study. | FBs are less likely to internationalise their operations than NFBs. Also, FBs are less likely to engage in networking with other businesses, which may explain why they struggle to internationalise their operations. | An FB is a firm that is majority family owned (50%) and has at least one family member in the management team. |

| Fernández and Nieto (2005) | Internationalisation Strategy of Small- and Medium-sized Family Businesses: some Influential Factors | Empirical Survey Probit and Tobit Models. | Family firms do not often choose to internationalise. The results confirm the negative relation between family ownership and international involvement, measured by both export propensity and export intensity. In other words, there are few family SMEs that export, and those that do export do so to a lesser extent than other SMEs. | An FB is a firm that belongs to a family, and one or more members of the owner family are in management positions. |

| Thomas and Graves (2005) | Internationalisation of the Family Firm: The Contribution of an Entrepreneurial Orientation | Empirical Business Longitudinal Survey (BLS) & case study. | Family firms are less likely to export than non-family firms. However, the difference in export intensity between family and non-family firms is not statistically significant. | An FB is a firm that is majority family owned (50%) and has at least one family member in the management team. |

| Fernández and Nieto (2006) | Impact of ownership on the international involvement of SMEs | Empirical Survey Probit and Tobit Models. | A significant relation exists between the type of ownership and the internationalisation strategy adopted by firms, and a negative relation exists between family ownership and export intensity. | A firm is an FB when there is one or more family members in managerial positions, and it has a corporate blockholder. |

| Graves and Thomas (2006) | Internationalisation of Australian Family Businesses: A Managerial Capabilities Perspective | Empirical Business Longitudinal Survey (BLS). | The managerial capabilities of family and non-family firms differ in function of their degree of internationalisation. Those of FBs lag behind the capabilities of their non-family counterparts as they expand internationally. | An FB is a firm that is majority family owned (50%) and has at least one family member in the management team. |

| Claver et al. (2007) | ¿Incide el Carácter Familiar en el Compromiso Internacional de las Empresas Españolas? | Empirical Survey. | The family nature of Spanish FBs influences positively, but not significantly, their IC, while firm size is one of their main internal facilitating factors. | An FB is a firm that is majority family owned (50%) and the general management is executed by one family member. |

| Claver et al. (2008) | Family firms’ risk perception: empirical evidence on the internationalisation process | Empirical Survey. | Risk perception decreases with the presence of the first generation and the size of these organisations. Additionally, the perceived risk is higher when the firm advances in its IC level. | Firms are family firms only when the family owns more than half of the business and when ownership and management coincide in family hands. |

| Graves and Thomas (2008) | Determinants of the Internationalisation Pathways of Family Firms: An Examination of Family Influence. | Empirical. Case study. | Most FBs follow a traditional pathway to internationalisation, with the key determinants of the pathway chosen being the level of commitment towards internationalisation, the financial resources available, and the ability to commit and use these financial resources to develop the required capabilities. | An FB is a firm that is majority family owned (50%) and has at least one family member in the management team. |

| Claver et al. (2009) | Family Firms’ International Commitment: The Influence of Family-Related Factors | Empirical. Mail survey. | The presence of family managers decreases the firm's likelihood of using international market entry modes that involve a high level of resource commitment. Also, there is a negative relation between the family ownership and the level of international resources commitment. | A firm is a family firm if most of its ownership and management lies in the hands of a family. |

| Gómez-Mejía, Makri, & Larraza (2010) | Diversification Decisions in Family-Controlled Firms | Empirical Randomised sample from Database. | Family firms diversify less than non-family firms, both domestically and internationally, and when they cross national borders they prefer to enter regions that are ‘culturally close’, in line with the Behavioural Agency Model (BAM). | An FB is a firm where there are two or more family members in management positions and at least 10% of shares with voting rights are owned by persons related to the family. |

| Kontinen and Ojala (2010b) | Internationalisation pathways of family SMEs: psychic distance as a focal point | Empirical Case Study. | Family SMEs mainly follow a sequential process and favour indirect entry modes before entering the French market. This market is psychically distant, but the case firms were able to overcome the distance by using different distance-bridging factors. Based on the findings, the authors argue that psychic distance has an especially important role in family SMEs’ internationalisation and foreign market entry (FME), mainly because of their general cautiousness due to family presence. | A family firm is a firm that is majority family-owned and has at least one family member in the management team. |

| Sciascia et al. (2012) | The role of family ownership in international entrepreneurship: exploring non-linear effects | Empirical Online Survey. | Basing their work on the stewardship and stagnation approaches, family ownership can have both positive and negative effects on the identification and exploitation of international entrepreneurship opportunities. The non-linear relation is inverted U-shaped. | The firm has to have been in business for over 10 years, have more than $1 Million in sales, be owned by a family, and have at least one family member in the management or on the board of directors. |

| Sciascia et al. (2013) | Family Involvement in the Board of Directors: Effects on Sales Internationalisation | Empirical Survey Regression Analysis | A non-linear relation exists between family involvement in the BOD and sales internationalisation. Moreover, the relation between family involvement in the BOD and sales internationalisation is J-shaped, whereas the relation between family ownership and sales internationalisation is inverted U-shaped. | The firm is a family firm according to independent survey firm TNS if more than 20% of the firm's equity is in family hands and more than one family member is in management or on the board of directors. |

| Segaro, Larimo, and Jones (2014) | Internationalisation of family small and medium sized enterprises: The role of stewardship orientation, family commitment culture and top management team | Empirical Survey. | A combination of the stewardship orientation of family and non-family members of the TMT and strategic flexibility makes FBs more prone to become international. Moreover, when non-family members are integrated in the TMT, FBs are likely to increase their IC. | An FB is a firm that belongs to a family with one or more family members in managerial positions. |

| Ownership & involvement | ||||

| Basly (2007) | The Internationalisation of family SME: An organisational learning and knowledge development perspective | Empirical Questionnaire. | Internationalisation knowledge positively influences internationalisation degree of the firm. The independence orientation does not significantly influence internationalisation knowledge. Social networking positively influences the amount of internationalisation knowledge. | The family firm is a firm controlled by one or more families involved in governance or management or at least holding capital stakes in the organisation. |

| Tri-dimensional definitions | ||||

| Self-perception, ownership & management | ||||

| Segaro (2012) | Internationalisation of family SMEs: the impact of ownership, governance, and top management team | Theoretical. | Distinctive familiness is made up of: survivability and patient capital, governance systems, social capital and human capital. This familiness has a positive influence on internationalisation in family businesses. | A family firm is a firm that belongs to a family with one or more members in managerial positions, and that is also viewed by the owners and/or managers as a family business. |

| Ownership, continuity & management | ||||

| Yeung (2000) | Limits to the Growth of Family Owned Business? The Case of Chinese Transnational Corporations from Hong Kong | Empirical. Case Study. | International strategy has become an effective way to grow for Chinese Family Businesses. Also, this strategy allows this kind of firm to socialise their more loyal non-family members, supply a better field for the successor and to consolidate personal and professional networks. | There is no explicit definition of FB, but FBs’ main characteristics are as follows: ownership, management and continuity by at least two generations of family members. |

| Kansikas et al. (2012) | Entrepreneurial leadership and familiness as resources for strategic entrepreneurship | Empirical. Case study. | Family businesses own a distinctive resource – familiness – that gives them a competitive advantage in developing an internationalisation strategy. | An FB is a firm where: 1) the owner works as CEO and/or chair of the board in the firm's main business; 2) at least one more family member owner (if existing) is active in the firm's main business; 3) at least one family member representing a different generational perspective from those in the previous two criteria is active in the firm's main business; and 4) at least one non-family member is active at the top management level in the firm's main business. |

| Tsao and Lien (2013) | Family Management and Internationalisation: The Impact on Firm Performance and Innovation | Empirical Database. | Family management and ownership can alleviate the negative effect of the increased complexity and uncertainty arising from internationalisation on firm performance and innovation. At the same time, compared to NFBs, family owners are better able to extract the benefits of internationalisation. Also, family firms differ from non-family firms along several features such as firm size, leverage, growth opportunity, and the industries they represent. | The family business concept is based on three criteria: 1) the involvement of the family in managing the firm; 2) the share of capital held by the family (ownership); and 3) the possibility of passing the business onto the next generation (continuity). |

| CONSTRUCT DESIGNED: “FBC4” COMPANIES ARE CLASSIFIED AS FAMILY BUSINESSES IF THERE ARE TWO OR MORE FAMILY MEMBERS IN MANAGEMENT POSITIONS, AT LEAST 10% OF SHARES WITH VOTING RIGHTS ARE OWNED BY PERSONS RELATED TO THE FAMILY, AND THEY HAVE UNDERGONE A SUCCESSION PROCESS | ||||

| HYPOTHESIS TO BE TESTED: H4a. There is a difference in the ID between FBC4 family businesses and non-family businesses. H4b. There is a difference in the IC between FBC4 family businesses and non-family businesses. | ||||

| Multi-dimensional definitions | ||||

| Self-perception, ownership, management & continuity | ||||

| Crick et al. (2006) | “Successful” internationalising UK family and non-family-owned firms: a comparative study | Empirical Survey & interviews. | There are no observable differences between family and non-family-owned firms in respect of measures of performance and sources of competitiveness in overseas markets using four main indicators: export sales volume, export sales growth, export profitability, and export market share. | A firm is a family business if: 1) the senior executive regards their company as a family business; 2) the majority of ordinary voting shares in the firm are owned by members of the largest family group that are related by blood or marriage; 3) the management team of the firm is comprised mainly of members drawn from the single dominant family group who own the business; and 4) the firm has experienced an inter-generational ownership transition to a second or later generation of family members drawn from the single dominant family group owning the business. |

| Ownership, management, involvement & continuity | ||||

| Kontinen and Ojala (2011) | Network ties in the international opportunity recognition of family SMEs | Empirical. In-depth interviews. | The weak ties of family SMEs quickly develop into strong ties. Family entrepreneurs are willing to put a lot of their own time into developing these ties, once they gain a sense of their goodness. This might be connected to the strong internal ties of family SMEs. Also, FBs control their resources by carefully searching for and developing new contacts. | A family firm is a firm in which the family: 1) controls the largest block of shares or votes; 2) has one or more of its members in key management positions; and 3) has members of more than one generation actively involved in the business. |

| Kontinen and Ojala (2012a) | Social capital in the international operations of family SMEs | Empirical. Case study. | Family entrepreneurs have a large number of structural holes when launching international operations, but also after several years of running international operations. Instead of trying to span structural holes they concentrate merely on developing the network closure with agents and subsidiary staff. The case firms spend a lot of resources on finding suitable network ties and on developing good network closure with the selected social capital ties. | A family firm is a firm in which the family: 1) controls the largest block of shares or votes; 2) has one or more of its members in key management positions; and 3) has members of more than one generation actively involved in the business. |

| Kontinen and Ojala (2012b) | Internationalisation pathways among family-owned SMEs | Empirical. Case study. | The ownership structure has the most important role in defining the internationalisation pathways followed by family-owned SMEs: a fragmented ownership structure leads to traditional internationalisation pathway whereas a concentrated ownership base leads to born global or born-again global pathways. | A family firm is a firm in which the family: 1) controls the largest block of shares or votes; 2) has one or more of its members in key management positions; and 3) has members of more than one generation actively involved in the business. |

| CONSTRUCT DESIGNED: “FBC5” COMPANIES ARE CLASSIFIED AS FAMILY BUSINESSES IF THE FAMILY CONTROLS THE LARGEST BLOCK OF SHARES WITH VOTING RIGHTS, ONE OR MORE OF ITS MEMBERS HOLD KEY MANAGEMENT POSITIONS AND MEMBERS OF MORE THAN ONE GENERATION ARE ACTIVELY INVOLVED IN THE BUSINESS | ||||

| HYPOTHESIS TO BE TESTED: H5a. There is a difference in the ID between FBC5 family businesses and non-family businesses. H5b. There is a difference in the IC between FBC5 family businesses and non-family businesses. | ||||

Source: The authors, based on Kontinen and Ojala (2010a) and Arregle et al. (2012).

We should note from the table how there are significant differences in the results obtained when using a less restrictive definition (i.e., self-perception) and a more restrictive one (e.g., ownership, management, involvement and continuity). Strategic behaviours and performance may differ, not only between family and non-family firms, but also among family firms with different attributes (Melin & Nordqvist, 2007). The theoretical assumptions to study the international strategy of FBs differ greatly in each study, as seen in the variety of conceptual frameworks used: international entrepreneurship; agency theory; stewardship theory; resource-based view of the firm; stages models of internationalisation; networking approach, and so on. Thus, different theoretical frameworks are useful to understand organisational processes and outcomes in family firms depending on the type of family firm considered (Arregle et al., 2012).

Whereas the same definition of FB has been used to analyse several important issues within their international strategy, authors have also deployed different definitions of FB to study the same aspect of their international strategy, which makes the results of comparisons nonsensical.

In this line, Piva, Rossi-Lamastra, and De Massis (2013) and Westhead and Howorth (2006), for instance, differentiate between family and non-family businesses using the self-perception criterion combined with the need for at least 50% of the company to be controlled by at least two members of the same family. However, whereas Piva et al. (2013) conclude that FBs in technology-intensive sectors have a greater chance of continuing their internationalisation strategies than NFBs, Westhead and Howorth (2006) find that firms with CEOs drawn from the dominant family group owning the business were less likely to be exporters.

On the other hand, self-perception as a family or non-family business may not be a sufficient criterion for determining this aspect. First, family businesses are often associated with small and medium-sized companies or even so-called craft and micro enterprises, and family businesses are hardly ever associated with large companies (Vallejo, 2007). Thus, a manager might consider the family nature of his or her company based exclusively on its size. Second, non-family firms might wish to imply that they are family businesses to be perceived as being more trustworthy and offering a stronger commitment, image and/or reputation, true strengths that characterise family businesses (Poutziouris, 2001). And third, family firms may not wish to reveal their true nature to conceal certain weaknesses often also associated with family firms, such as lack of professionalism, a certain degree of nepotism and lack of clear organisational structures due to overlapping roles (Poutziouris, 2001). In view of the foregoing, considering solely the perception of managers and/or owners of a company to be considered an FB or NFB can lead to errors.

Following the above-mentioned arguments the construct “FBC1” was designed and hypotheses 1a and 1b proposed (see Table 2).

As far as the ownership criterion is concerned, various studies on the international strategy of FBs have only used it for differentiating between family and non-family businesses. Among the papers that pursue the same objectives are Arregle et al. (2012) and Calabrò, Campopiano, Basco, and Pukall (2016). Both studies differentiate between family and non-family businesses by considering that ownership by persons outside the family should not exceed 49%, and their research results are similar. Whereas Arregle et al. (2012) show how the presence of non-family members on the board of directors (BOD) provides family businesses with the necessary resources to support their international strategies, Calabrò et al. (2016) find that a high involvement of non-family members in the governance structure has a positive impact on family firms’ pace of internationalisation. Thus, we have designed, based on the foregoing and considering ownership as the only criterion, the “FBC2” construct, and propose H2a and H2b (see Table 2).

In the third place, we highlight ownership and desire for continuity as differentiating aspects between family and non-family businesses, since the desire for the business to continue in the hands of the next family generation or the actual transfer of the business are crucial aspects in defining family or non-family firms. Various authors have used these two criteria to define an FB in their studies of international strategy (Casillas, Moreno, & Barbero, 2010; Crick, Bradshaw, & Chaudhry, 2006; Zahra, 2003). Similarly, Zahra (2003) shows how ownership is a significant variable that determines the degree and geographic scope of internationalisation, which supports Stewardship Theory.

Thus, we have designed, based on the ownership and continuity criteria, the construct “FBC3” and propose H3a and H3b (see Table 2).

The fourth combination we consider to construct our FBC4 concept (see Table 2) is made up of the criteria: ownership, continuity and management. The construction of FBC4 comes after reviewing a body of work (Claver, Rienda, & Quer, 2007; Claver, Rienda, & Quer, 2008; Claver, Rienda, & Quer, 2009; Colli, García-Canal, & Guillén, 2013; Graves & Thomas, 2008; Segaro, 2012) that combines ownership and management or, even, family involvement in the business (through ownership and management, again). In this line, Segaro (2012) reports that different levels of family involvement in the ownership and management of the business could lead to distinct degrees of internationalisation in family businesses. Most studies that have defined FBs following the ownership and management criteria coincide in concluding that they are less likely to engage in exporting, measured by export propensity and export intensity, managerial capabilities being one of their main limiting factors (Graves & Thomas, 2006). This coincidence remains when they analyse the firms’ IC. Claver et al. (2009); Claver et al. (2008) conclude that there is a negative relation between family ownership and management and the level of international resources commitment, with risk aversion (Claver et al., 2007; Gómez-Mejías, Tàkacs, Núñez-Níquel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007), psychic distance (Kontinen & Ojala, 2010b), their low level of engagement in networking with other businesses and, at the same time, losing opportunities to enhance their competitiveness from symbiotic international business networks (Etemad, Wright, & Dana, 2001) some of the factors hindering FBs from becoming international.

But in addition to ownership and management, other authors have also considered continuity (Casillas & Acedo, 2005). Thus, several researchers consider these criteria to distinguish between family firms and other companies (Kansikas, Laakkonen, Sarpo, & Kontinen, 2012; Tsao & Lien, 2013) in their studies on the internationalisation of FBs. They conclude that these firms possess certain resources, such as personal and professional ties, that can alleviate the negative effect of the increased complexity and uncertainty arising from internationalisation on the firm. These resources configure these firms’ distinctive familiness, which gives them a competitive advantage in their ID (Kansikas et al., 2012).

All the above-mentioned arguments have contributed to defining our fourth concept “FBC4” and to establishing H4a and H4b (see Table 2).

Finally, we have defined a yet more restrictive concept of FB through the criteria ownership, continuity, management and involvement.

Involvement is related to the family's influence on company strategy and the distinctive “familiness” of the business and it has become one of the most controversial issues confronting the Components Approach, which Basco (2013) calls Demographic Approach, and the Essence Approach (Chrisman, Chua, & Sharma, 2005). Family involvement in the business is highlighted by Astrachan et al. (2002), who define an involvement indicator measuring the power exerted by the family over the business, as well as the transmission of the family culture and its experience to the business (through the design of the F-PEC scale).

The criteria of continuity, management and involvement have also been used to identify FBs in the literature on their IS. Along these lines, Kontinen and Ojala (2012a) define FBs as companies in which the family controls the largest block of shares with voting rights, one or more of its members hold key management positions and members of more than one generation are actively involved in the business. Although these authors explain this definition based on their consideration of two criteria – ownership and management – it is clear that it also takes into account family involvement in the business, as well as continuity since the definition alludes to the involvement of different family generations. These aspects have allowed us to develop our fifth construct of FB, “FBC5”, and to propose hypotheses 5a and 5b (see Table 2).

Thus, this work tries to analyse whether internationalisation is different depending on whether the FB definition is based on all four criteria (ownership, management, continuity and self-perception) or on one, two, or three of them. Differences in types of FBs – or business families – might well be related to differences in the internationalisation process and its outcome.

Despite the above, and although we can find many theories, paradigms and approaches in the literature to explain the main business motivations for opting for ID and for deploying higher or lower levels of IC, we cannot say that some are better than others; they all complement each other (Villareal, 2010).

Moreover, there are many research contributions around the business internationalisation concept. Thus, researchers consider the level of business commitment, the geographical scope of activity, the changing process involved in the development of this strategy, among others. For instance, Andersson (2002) defines internationalisation as the firm's level of commitment to international activities, whereas Laguna (1997) alludes to the need for the geographical scope of activities to go beyond the national market. Likewise, several authors (Root, 1994; Welch & Luostarinen, 1988) combine the commitment level and geographical scope of activities criteria to conceptualise business internationalisation.

There are concepts considering the international strategy as a changing process that involves operating in new markets (Karlsen, Silseth, Benito, & Welch, 2003). Finally, several authors (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977; Melin, 1992) conceptualise business IS as the result of combining the above-mentioned three aspects: the firm's level of commitment to international activities; the geographical scope of activities; and the consideration as a process of change. But all these definitions complement each other, and the criteria most often used to conceptualise business internationalisation strategy are the geographical scope and the level of commitment. Following the geographical scope criterion, the current work considers that the firm is developing internationally (ID) when it goes beyond its domestic market.

In turn, the IC level is generally measured by two items: first, export sales as a proportion of total sales, and second, the entry modes used to embark on ID.

Many authors have analysed the choice of international entry mode (Anderson & Gatignon, 1986; Pla, 2000; Root, 1994; Sarkar & Cavusgil, 1996; Tsang, 1997), but these studies refer to exports and foreign direct investment (FDI) as the most generic alternatives. The former, exports, implies producing in the country of origin and selling in different countries (Suárez, 2005), either by using intermediaries or through the export department (Pla, 2000). Chang and Rosenzweig (2001) define FDI as the investment that implies ownership and allows an effective control system. It involves establishing production or sales facilities in international markets by acquiring existing businesses in these markets, by creating new subsidiaries or by joint-ventures with other partners.

In the business population studied, the firms rarely choose FDI as an entry mode2 in international markets, but prefer exporting, so IC will be measured only through exports as a proportion of total sales volume.

All the above-mentioned arguments try to respond to Kontinen and Ojala's (2010a) proposal for future research and are summarised in Fig. 1.

From the literature review this figure summarises the variables that, individually or in combination, have most often been used to distinguish between family and non-family businesses. The figure also shows the research hypotheses proposed in this study, which combine several concepts of FB and examine the potential influence of their use on the firm's international development (ID) or otherwise and on its commitment to foreign markets once it has decided to become international (IC).

3MethodsThe study population comprises Spanish wine and olive-oil production companies for the following reasons. The first is the significant weight of foreign trade operations conducted by companies in these subsectors, since Spain is a global leader in both the wine and olive-oil sectors. The second is that family firms are extremely rare in the Spanish olive-oil sector, where most companies belong to cooperatives, despite the importance of FBs to the Spanish (and world) economy. In contrast, most companies in the Spanish wine sector are family firms (Fuentes-Lombardo, Fernández-Ortiz, & Cano-Rubio, 2011).

The study population was defined based on the secondary information available, namely the databases of companies in both sectors kept by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Environment, together with the databases of the Regulatory Boards of the most representative Designations of Origin in the Spanish wine and olive-oil sectors. When determining which wine and olive-oil producing companies to include in the study population, the information contained in the SABI database of accounting data from Spanish firms was also used.

A quantitative methodology was used to test the research hypotheses. Self-administered on-line questionnaires were applied, completed by the CEO, to collect information from primary sources.

The instrument for gathering information was developed based on Churchill and Surprenant's (1982) methodology to construct measurement scales. Thus, first, each construct in the study was defined and all the potential dimensions were extracted from the literature reviewed. The items obtained were complemented with in-depth interviews with academics and wine and olive-oil experts. Specifically, this pilot test to validate the questionnaire was conducted with managers of wineries and olive-oil mills, senior representatives of the Regulatory Boards of the Designations of Origin and associations and foundations from the wine and olive-oil sectors. A pre-test was conducted among industry experts and the questionnaire was completed excluding redundant or non-clarifying items.

The questionnaire included items to identify the family nature of the companies in accordance with the different criteria considered in the theoretical framework, and items to measure the firms’ international development (ID) and their commitment to international markets (IC).

In the case of international development (ID) or export propensity (Fernández & Nieto, 2005; Fernández & Nieto, 2006), the questionnaire included two items: one to detect whether the companies conduct international business, and the other how they conduct international business and penetrate international markets.

IC was measured using an item in which the companies were asked to indicate their sales in international markets as a proportion of total sales volume. This is labelled export intensity by several authors (Arregle et al., 2012; Fernández & Nieto, 2005; Fernández & Nieto, 2006; Graves & Thomas, 2008).

Table 3 provides the statistical data to identify population, sample, measurement instrument and the type of statistical analysis used in the empirical study. Data gathering was supported by telephone contact and an e-mail containing a link to the questionnaire.

Summary of statistical data analysed.

| Population | Total: 3925 2659 firms in wine sector 1266 firms in olive-oil sector |

| Country | Spain |

| Sample | Total: 418 257 from wine sector 161 from olive-oil sector |

| Data collection period | March to September 2014 |

| Response rate | 10.7% |

| Confidence level | 95% |

| Sample error | <5% |

| Measurement | On-line ad-hoc questionnaire |

| Questions | Total: 11 8 about family firm concept 3 about international strategy |

| Statistical analysis applied | Difference of means test |

Source: The authors.

According to the theoretical framework, five (5) variables were created for each of the five concepts designed: FBC1: FB based on self-perception; FBC2: FB based on ownership; FBC3: FB based on ownership and desire for continuity; FBC4: FB based on ownership, desire for continuity and management; and FBC5: FB based on ownership, desire for continuity, management and involvement.

The existence of statistically significant differences in ID between family and non-family businesses was tested based on the five concepts indicated above and using contingency tables. The difference of means test, carried out for each of the five FB concepts indicated above, was used to study the existence of statistically significant differences between the two groups of firms in their degree of IC, measured according to export intensity (exports as % of total sales), since most of the companies in the sample state that they had not used other means of developing their international activities other than exports. This result confirms that exporting is one of the most popular business strategies to become international (Ruppenthal & Bausch, 2009).

4Results and discussionThe FB concept used to differentiate FBs from NFBs influences firms’ international development (ID) and their commitment to international markets (IC). When this differentiation considers only the perception of the firm's CEO (FBC1), the results show that family businesses develop internationally (ID) more frequently than non-family ones. But since the differences identified between the two groups of companies were not significant, we must say that when classifying companies based on “self-perception” there are no differences in terms of choice and implementation of an IS. This provides support for Hypothesis 1a, and may be due to the persistent confusion regarding the definition of the family or non-family nature of a company (Vallejo, 2007), as well as the arguments in Section 2. However, when the “ownership” dimension is considered (FBC2), significant differences in international development are observed, in favour of FB. This provides support for H2a.

Something similar occurs when the differentiation is made on the basis of “ownership and continuity” (FBC3), since significant differences (99%) are observed between family and non-family firms in relation to whether or not they target non-domestic markets. These differences again favour FBs, since they opt for ID more frequently than non-family businesses, hence providing support for H3a. However, when ownership and/or continuity are the only dimensions considered when classifying FBs and NFBs, the companies do not necessarily have to be managed by family members or to have high levels of family involvement in the taking of strategic business decisions. Thus, the company management may be controlled by directors outside the family who can help overcome the lack of professionalism and the nepotism and rigidity in adapting to new challenges (Poutziouris, 2001) and greater risk aversion exhibited by family-owned companies, increasing the likelihood that the company will opt for ID.

When the FB concept includes the “management” dimension, the results are inverted and reveal that NFBs are more inclined to opt for ID (90% significance). This provides support for H4a, concerning the existence of differences in the international activity of family (FBC4) and non-family firms. Identical results are obtained in H5a, which assumes that family members are actively or very actively involved in the company (FBC5). Previous research using the aforementioned variables to define the concept of FB (Cerrato & Piva, 2012; Fernández & Nieto, 2006; Fernández & Nieto, 2005) also finds a negative relation between the family-nature of the company and ID, indicating that strong family involvement in the business management can lead to a shortage of managers capable of managing the company's operations in non-domestic markets. Fig. 2 shows the results obtained in this work from testing the hypotheses concerning the ID.

The results vary when the variable measured is the IC of companies that opt for ID. In this case, H1b can be rejected because there are significant differences (90%) between the IC of family and non-family businesses in favour of the former (foreign sales are 32.05% and 25.91% of total sales, respectively). Members of family businesses often boast of their pride in their company and the product they manufacture based on the knowledge and experience of the family tradition, which makes them more committed to long-term strategies (Poutziouris, 2001); the internationalisation strategy is of course a long-term strategy (Colli et al., 2013; Graves & Thomas, 2008). Moreover, the fact that more than one family generation has continuously and successfully produced a good or provided a service is a source of satisfaction for its members. Seeing the family surname linked to the business name and/or brands, or knowing that its products are marketed all over the world as a result of the ingenuity and hard work of past family generations, becomes a source of pride for current generations that will be transmitted to future ones, leading to a high level of commitment, which may explain the decision to embark on ID in family businesses. Their strategies are more successful than those of non-family businesses.

When the criteria to classify companies are based on ownership (FBC2) and ownership and continuity (FBC3), the results are similar (32.63% vs. 24.32% and 32.27% vs. 25.36%, respectively). The level of IC of differs significantly between family and non-family businesses, being higher in the former, hence providing support for H2b (99% significance) and H3b (95%). With regards ownership, an FB could be defined when only part of the company is controlled by the members of the same family (51%, as in the case of FBC2), which implies that ownership may be shared with people outside the family, hence increasing their IC (Fernández & Nieto, 2006).

When continuity is also considered (FBC3), an organisational culture is created that may encourage risk taking through the exploration of international growth opportunities (Zahra, 2003), or, there may be a desire to transition the reins of the company to the next family generation, which entails orienting the company towards growth targets. Internationalisation is one strategic option that can guarantee growth (Claver et al., 2008), and with it the long-term survival of the company. These are both priorities that characterise family businesses (Harris, Martínez, & Ward, 1994), and they may lead to a higher level of commitment to ID.

The empirical results fail to provide support for H4b. According to the construct FBC4, even though it may be said that family businesses are more committed to exports than non-family firms (31.95% vs. 26.85%), these differences in their IC are non-significant. Indeed, companies managed by family members (FBC4) may exhibit a lack of professionalism that can reduce their level of IC compared to more professionalised firms (Cerrato & Piva, 2012). Previous studies have shown how managers’ lack of international experience can negatively impact the internationalisation of family firms (Graves & Thomas, 2008).

Finally, when a high degree of family involvement is considered in the FB concept (FBC5), this research fails to confirm H5b and no significant differences are observed in the IC between the two groups of companies. This could be explained by the greater involvement of family members in the running of the business, the ownership, the management and the BOD. Thus, the presence of people from outside the company within those dimensions favours the internationalisation of family businesses (Arregle et al., 2012; Sciascia, Mazzola, Astrachan, & Pieper, 2013). These assumptions may be present in FBC1, FBC2 and FBC3, and to a lesser extent in FBC4 and FBC5; thus (non-significant) differences are also observed in the IC of family and non-family businesses in H4b, with a slightly stronger commitment in family firms.

According to the different FB concepts considered here, the main research results from the analysis of IC between family and non-family businesses are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4 summarises the main empirical results concerning the ID and IC, distinguishing between family and non-family businesses.

5Contributions, implications and future researchThe purpose of this study has been to show that the definition of family business (FB) matters, to the extent that different studies on FBs’ international strategies obtain multiple and diverse results that cannot be generalised.

FBs and NFBs have been distinguished using five different concepts of FB, after identifying the most commonly used criteria in the literature (management perception, family ownership, desire for continuity, family management, and family involvement in the business) and their combinations. The results reveal differences between the international development (ID) of family and non-family firms depending on the concept of FB used, and in some cases also differences in their international commitment (IC).

First of all, when the concept of FB is based on self-perception as a family or non-family business, there are no differences in ID between these types of firm. But when a broader concept of FB is used, with only the requirement that family members have to own at least 51% of the company, or additionally that there has to be a desire for continuity, the international development of these companies is greater than that of non-family businesses. Making the definition of this concept more restrictive by adding other dimensions such as family management of the company or high or very high levels of family involvement in the business, inverse results are obtained and the results show that non-family firms show stronger ID than family businesses.

Something similar is observed in the IC of companies that have embarked on ID. When management perception is the chosen dimension to differentiate family and non-family businesses, the results reveal that the former are more committed to internationalisation; the same occurs with ownership and also when this dimension is combined with continuity. However, when the FB concept is more restrictive, including family management and family involvement in the business, no differences are observed in the IC between family and non-family businesses.

These results coincide with those reported in previous research. Thus, it is advisable not to conceptualise FB as a dichotomous or homogeneous variable, but to consider it as a continuous variable. In this sense, Kontinen and Ojala (2010a) also recommend differentiating firms according to their position on a continuum, where the position is determined by the degree of family ownership, management and involvement and by the desire for the company to remain in the hands of the next family generation. These authors argue that knowledge of FBs’ international strategies would be enriched if these companies are studied in that manner.

Likewise, Mitter, Duller, Feldbauer-Durstmüller, & Kraus (2014) consider that it is neither necessary nor productive to choose a single theory among the FB theoretical perspectives, since each theory may provide a unique insight into a specific situation or in a specific context of this type of firm. In this line, with regards Agency Theory in the governance of family business, the FB concept used is relevant to analyse the agency costs created as a result of the separation of ownership and control. Thus, the constructs FBC2, FBC4 and FBC5 are the most used concepts in the literature on family businesses considering ownership, management and involvement as the main variables to define an FB.

In contrast to Agency Theory we find Stewardship Theory, which assumes a humanistic model of man. The steward's behaviour is based on serving others and therefore the steward will align their objectives with the principal's interests. Governance structures that empower stewards are prescribed to facilitate the continued alignment of interests, principally between owners and managers. Thus, the same above-mentioned concepts, FBC2, FBC4 and FBC5, are the most suitable to analyse firms’ IS from this theory. Moreover, and according to Stewardship Theory, firms with family involvement have a positive influence on internationalisation (Carr & Bateman, 2009).

The third theory useful in studying FBs is the Essence Approach, grounded on the behavioural perspective (Cyert & March, 1963). From this approach two different streams have emerged to interpret the essence aspects of family firms: the “familiness” stream and the “socioemotional wealth” (SEW) stream. The “familiness” stream (Habbershon & Williams, 1999) aims to recognise idiosyncratic firm-level bundles of resources and capabilities (Chrisman, Chua, & Litz, 2003; Habbershon et al., 2003) as well as specific behaviours (Zellweger, Eddleston, & Kellermanns, 2010) resulting from the family-business interaction. The SEW stream (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007) attempts to identify the family firm's potential motivation to behave differently and the reasons why family firms use specific resources and capabilities (Basco, 2013). Under the umbrella of this behavioural perspective, FBC1, FBC4 and FBC5 are the most suitable constructs to study the international strategy of FBs.

Thus, one of the main conclusions of this work is that FBC4 and FBC5 could help to make the component and essence approaches converge, being the most suitable FB definitions to advance the major theories of family businesses (Agency and Stewardship Theories, Resource-Based View, Familiness and SEW stream, among others).

The second conclusion to be highlighted is that the concept FBC2 is the notion of FB that, within the above-mentioned continuum, is most applicable to non-family businesses–called “private companies” (Vallejo, 2007)–while FBC5 firms exhibit the highest degree of “familiness”, and so correspond to “pure family businesses” (Cerrato & Piva, 2012; Vallejo, 2007), characterised by a lower perceived degree of ID and IC in foreign markets (Fuentes-Lombardo & Fernández-Ortiz, 2010).

Thus, the results of this study show the influence of using different FB concepts not only on the internationalisation results but also on the IC of these companies, being of interest to both academics and business practitioners. Thus, family businesses defined here by the concepts FBC4 and FBC5 seem to display lower levels of ID and IC than family firms defined by FBC1, FBC2 and FBC3, as Fig. 5 shows.

This result suggests that family commitment to the running of the business and its management, which are both shared with people from outside the family, can boost the FBs’ international strategy and enhance its success.

The current research has a number of limitations. The first is that only five dimensions were considered to conceptualise FBs, although combinations thereof could give rise to many other notions that were not analysed here. A second limitation is that this study only compares differences in ID and IC between family and non-family firms, but not among the five groups created.

Based on the foregoing, future research should consider other possible combinations of the dimensions to conceptualise FBs and their possible influence on the results of family firms’ international strategy compared to NFBs. Furthermore, each of these dimensions could be studied at different levels. For instance, family business ownership could yield different results if the family owns a 51% stake or higher in the business than if the company is wholly family owned. Something similar could occur depending on whether family members occupy a minority, a majority, or all of the directorships.

With regards business continuity, different results could be obtained if the founder wishes to hand over the reins of the business to the next generation compared to if the company has already transitioned to the second, third or subsequent family generations. The perception of the managers and/or owners of the company that it is a family business or not is a dimension that has yet to be analysed in depth, since founders who own all the shares in their companies sometimes decide not to pass the business on to family members of successive generations for different reasons. However, in research in which the concept of FB has only been addressed from an ownership perspective, the company in question would in fact be considered an FB, contrary to the perception of its founder. In contrast, an FB acquired by persons outside the family should no longer be considered an FB, although its new owners may continue to describe it in that way due to its history as a family firm.

Future research should consider the family nature of companies as a continuous variable, defining the dimensions to be considered and the degree to which each of them, whether individually or collectively, influences the international strategies of these companies.

This research work has been developed thanks to a grant awarded by the University of Jaén (Spain) to make the Research Project with the code number UJA 2013/08/14 and sponsored by the Foundation Caja Rural of Jaén.

The full version of this table is in the supplementary material.

Spanish wineries invested a mere 20,396.95 € in FDI in 2013, whereas Spanish olive-oil mills produced literally zero FDI in the same time period (FDI statistics, Spanish Economic and Competitiveness Ministry, 2015).