Ethnocentric conduct among employees is observed in multicultural work environments characterised by the presence of individuals from diverse origins. The existence of ethnocentrism inside the workplace has been observed to have repercussions for colleagues. Nevertheless, despite the significance of the aforementioned factors, there hasn't been a considerable pertinent scholarly study on how these aspects affect the localisation of human resources. This research closes the gap in the literature by integrating ethnocentrism and human resource localisation variables. We used Andrew F. Hayes PROCESS V4.0 to assess the hypothesised relationship between employees' ethnocentric behaviour and human resource localisation success. In addition, employee knowledge-sharing tendency works as a mediator, and employee cultural intelligence (CQ) is a moderated mediator. From the analysis of 361 respondents from multinational Company (MNC) workers, we found that ethnocentric behaviour reduces employee knowledge-sharing tendency among workers and, in return, reduces human resource localisation success. However, CQ moderates the mediated relationship between employee knowledge-sharing direction and localisation success. We also found that when employees have high CQ, the negative effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success weakens. Managers of multicultural organisations should reduce ethnocentrism to ensure the success of human resource localisation. MNCs can consider employing culturally intelligent individuals and giving them sensitivity training. Future research can integrate other variables, such as the firm's cultural characteristics, to continue this research domain. Further research can also consider collecting data from nations with high cultural distances; comparative studies between two countries are also encouraged.

Earth's population is typically considered one unit because all individuals are the same species. Nevertheless, throughout human history, it is evident that people have readily divided themselves into several diverse groupings (Mihalyi, 1984). Individuals frequently segregate themselves into distinct factions for a multitude of reasons, and ethnocentrism is a significant component that might influence this conduct. Thinking of oneself at the centre of everything signifies ethnocentric behaviour. Ethnocentrism is a sociological and anthropological notion pertaining to the belief or perception of one's ethnic or cultural group's superiority over others. It involves employing one's cultural framework as the benchmark for assessing and appraising different cultures' customs, behaviours, beliefs, and values (Durnell & Hinds, 2004). Individuals or civilisations that display ethnocentrism sometimes perceive their own way of life as the "correct" or "standard" one while regarding other cultures as peculiar, inferior, or potentially menacing (Kessler & Fritsche, 2011). This perspective has the potential to result in biased attitudes, discriminatory behaviours, and a limited comprehension and valuation of the wide range of human cultures. Ethnocentric behaviour is very obvious when individuals come from different backgrounds.

Ethnocentrism has the potential to show itself at both the individual and communal levels. At the individual level, manifestations of cultural bias can be observed in the form of prejudiced views towards individuals of diverse cultural origins and the inclination to perceive one's cultural standards as universally valid. When seen collectively, ethnocentrism has the potential to foster a perception of national or cultural superiority, leading to intergroup conflicts, unhealthy relationships with coworkers, low skill transfer, lack of tolerance etc. Ethnocentric ideas arise from a profound sense of identity with one's own culture, leading to a biased and favorable perception of that culture. This behaviour is ubiquitous in multicultural workplaces worldwide. A study conducted by Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner (2010) revealed that headquarters managers operating in the region had an unfavorable stereotyped perception of the residents of the United Arab Emirates. This perception influences the formulation of policies on the localisation of labor. Multinational companies (MNCs) subsidiaries are the best example of multicultural workplaces where employees come from different cultures and co-mingle at the office. Research in international human resource management has shown that MNCs prioritise the localisation of their staff in foreign subsidiaries to enhance operational performance by connecting with local society and government to increase market share (Lundan & Cantwell, 2020). Bhanugopan and Fish (2007) claimed that localisation is a process in which host country employees develop their skills and, as a result, their efficiency. The primary goal is to train and develop local employees so that they can have a firm-specific advantage and can competently and efficiently replace expatriates (Meyer & Xin, 2018). Localisation success is not just replacing expatriate employees with local employees; instead, it is replacing expatriates with competent local employees who can perform the same as expatriate employees (Jain et al., 2015). Researchers highlighted the significance of both selecting significant local human resources and utilising relevant internal skills to develop and deploy them in such a way as to create firm-specific assets that are uncommon, unique, and non-replaceable, leading to a sustained competitive advantage (Dickmann et al., 2019). So, success in human resource localisation is impossible without the proper coexistence of expatriate and local employees in the workplace. Coexistence and tolerance among employees ensure a healthy work environment where employees prefer to exchange ideas to improve skills and efficiency. However, workers' ethnocentric attitude severely affects the friendly working relationships among employees at the workplace.

Nevertheless, Current ethnocentrism research emphasises organisations' ethnocentric policy and consumer study. Ethnocentrism is widely used in consumer behaviour and brand image research (Kusumawardani & Yolanda, 2021; Areiza-Padilla & Cervera, 2023). Consumer ethnocentrism may be described as the view that purchasing foreign-made goods is not ethical and moral. Previous studies have elucidated ethnocentrism from many viewpoints, such as country of origin is significantly associated with the international shopping behaviour of a person and brand behaviour (Farah et al., 2021; Hong et al., 2023), tourist ethnocentrism (Lever et al., 2023), correlation of game and ethnocentrism (Ferguson, 2023), Ethnocentrism and Sexism (Pratto & Pitpitan, 2008), Islamic religiosity and ethnocentrism (Karoui et al., 2022). Firms with ethnocentric global talent management policies are more likely to push head office employees to get foreign experience and to create a barrier for local talent to climb the top of the ladder (Banai, 1992). Tran and Selvaraj (2018) described ethnocentrism from an inter-ethnic and discomfort interaction perspective. Therefore, researchers focus less on employees' ethnocentric behaviour in the multicultural workplace and its impact on employees' knowledge-sharing tendency and human resource localisation success. The goal of the present research is to close this gap by examining and evaluating the impact that workers' ethnocentric conduct has on the effectiveness of human resource localisation, especially in multicultural organisations.

Thus, this study investigates the potential effect of workers' ethnocentric behaviour at the office, knowledge-sharing tendency, and workers' cultural intelligence on the success of localisation efforts. The primary objectives of this study are to evaluate the impact of ethnocentrism and knowledge-sharing behaviour on the achievement of localisation success. This research aims to fulfil three key research purposes: this study contributes to the existing literature on employee ethnocentric behaviour at the workplace and its influence on workers' knowledge-sharing behaviour within multicultural work environments. Furthermore, this study contributes to the current body of literature on employee cultural intelligence (CQ) by examining the impact of CQ on employee knowledge sharing and staff localisation. The study's third aspect elucidates how employees' ethnocentric behaviour hampers the achievement of success in human resource localisation, and this hindrance occurs through a meditational pathway in the form of employees' inclination to share knowledge. The findings of this study offer empirical support for the aforementioned research gaps and provide recommendations for multicultural firms seeking to create a positive work environment in a diverse workplace.

The subsequent sections of this article are organised in the following manner: Following a thorough introduction that provides the rationale for our work Section 1, we proceed with four further sections. Section 2 provides a comprehensive summary of current literature reviews and the process of developing hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the study methodology, whereas Section 4 presents the findings of the investigation. Lastly, Section 5 includes the discussion and concluding remarks.

2Literature review2.1Ethnocentrism in the workplaceResearchers suggested that employees' aggregate beliefs towards everyone else, thoughts, and resources influence the effectiveness of decisions about organisational structure, management, and the identity of an increasingly global organisation (Abdallah, 2023). A mindset or attitude in which workers prioritise their own cultural group over others is known as employee ethnocentrism (Sumner, 1959). Executives with ethnocentric attitudes tend to think highly of themselves, thinking they are more trustworthy and dependable than their peers (Lee & Hwang, 2024). This prejudice can take many forms, including favouring coworkers who share the same cultural background, hiding knowledge with out-group members, forming unfavourable assumptions or prejudices about individuals from other cultures, diminishing team cohesion, or opposing initiatives to promote diversity and inclusion in the workplace (Pan et al., 2021; Chae et al., 2022). Employee ethnocentrism in a multicultural workplace can lead to several problems. Employee preference for their own ethnic group might cause divides and cliques within the organisation. This can make it more challenging to accomplish shared objectives by impeding efficient communication, teamwork, and cohesiveness. Multicultural workplaces frequently gain from a diversity of viewpoints and concepts but employee ethnocentrism may damage an organisation's image, reducing its appeal to prospective talent and perhaps affecting its competitiveness in the global market. (Wadhwa & Aggarwal, 2023). Employee ethnocentrism discourages exchanging alternative ideas and methods, which can impede innovation and localisation of the workforce and business. Ethnocentric views can potentially cause miscommunications and disputes amongst workers from various cultural origins. This type of employee in the top positions of any organisation might create a "glass ceiling" for other employees (Scullion & Collings, 2011). A hostile or stressful work atmosphere may result from this. In the contemporary globalised business landscape, enterprises seeking to broaden their market reach must acknowledge and honour the diversity of cultural practices. An organisation's capacity to engage with and cater to a variety of clientele may be hampered by ethnocentric viewpoints.

2.2Ethnocentrism and human resource localization successEmployee ethnocentric attitude always creates "us-and-them" at the workplace, dividing employees into several classes. A healthy relationship among employees is impossible when several employees segregate themselves into several likely groups. Because ethnocentric individuals use their own culture as a measurement tool for other cultures, they have a tendency to believe that their culture is superior and to see different cultures as inferior and strange (Michailova et al., 2017). Thus, ethnocentrism is a barrier between employees' healthy cooperation for task accomplishment and efficiency because the in-group considers out-group people to be inferior, weak, and immoral, and there is no collaboration with them.

One area of management where MNCs are likely to adapt their methods to the local culture is human resource management (HRM), for both institutional and cultural reasons (Latukha et al., 2020). Effective human resource management in geographically separate subsidiaries is essential for international corporations since various human resource (HR) systems come from specific differences in distinct nations' historical, cultural, and institutional histories (Cooke et al., 2020). Human resource localisation refers to the degree to which workers from the host nation fill positions held by foreign workers. According to Budhwar et al. (2019), "workforce localisation" refers to a set of practices that prioritise hiring and promoting natives over foreign workers for jobs within an organisation. In MNCs, expatriates are workers dispatched from the parent or third country to the local subsidiary (Fee, 2020). In global corporations, workers hired from the local labour market in the host country are known as host country personnel.

Human resource localisation is closely related to properly recruiting and training competent local job seekers (Tamer et al., 2023). After successfully retaining skilled employees, the locals will replace the expatriate or parent country nationals, and the local employee must have the same or more competence level as the expatriate. In this whole process, expatriates and the locals must work together and exchange ideas and skills for future competency (Bhanugopan & Fish, 2007). Employees involved in the replacement process need to provide social support to each other at the workplace. If the expatriate, the local, or both hold, ethnocentrism might stop learning from each other. Thus, local employees will be less competent in replacing expatriates. Research by Farh et al. (2010) described three types of social support for eliminating barriers between two parties: First, expatriates must be responsive to help and criticism from coworkers in the host country. Second, coworkers in the host country must feel that the expatriates are open to accepting help and criticism. Third, Colleagues in the host country should be keen to offer support and feedback. In addition to being an interactive learning process, localisation is challenging for staff members since it requires extensive training and development.

Nevertheless, skill transfer is severely hindered when an employee becomes ethnocentric and does not properly cooperate with coworkers (Wong, 2005). Thus, local workers cannot learn from expatriate employees and vice versa. Therefore, employee's ethnocentric attitude hampers the localisation process, and the workforce localisation process can only be effective with the assistance of both parties.

Hypothesis 1

Ethnocentrism has a negative effect on human resource localisation success.

2.3Employee knowledge-sharing tendency: the mediating roleThe concept of employee knowledge-sharing propensity pertains to the inclination of employees to disseminate their information, skills, and expertise among their peers (Obrenovic et al., 2020). Knowledge sharing may be a valuable strategy for individuals to effectively manage hard, risky, and uncertain situations by bolstering their confidence and enabling them to develop innovative solutions (Khan et al., 2023). Assuming that personnels are willing to actively contribute their knowledge and experience to their colleagues and actively participate in collaborative endeavours across diverse cultural backgrounds. In this scenario, using such an approach has the potential to facilitate the amelioration of cultural disparities and facilitate the transmission of fundamental proficiencies and information to the labour force, hence augmenting the process of localisation. However, employees may not always be eager to share information because of personal beliefs, even in the face of several initiatives to encourage knowledge sharing in organisations (Anand et al., 2020). Employee ethnocentric behaviour can lead to a preference for interaction among one's own group rather than all, which may result in limited diversity and a lack of expertise in the organisation. There are various levels at which knowledge sharing can take place. Individuals may choose to reveal or withhold knowledge based on their willingness and intention when sharing it with another individual, a group, an organisation, or another individual (Anand et al., 2019). According to Gagné et al. (2019), knowledge is a precious resource, and sharing it depends on the individual who chooses who to share it with, when to share it, and why. Employees who exhibit ethnocentrism tend to possess a tendency to withhold knowledge, exhibit resistance toward collaborating with colleagues, and struggle to adapt to new practices. This behaviour can have negative consequences on the localisation process by maintaining cultural barriers, diminishing the transfer of knowledge, and obstructing the organisation's capacity to integrate effectively with the local environment. Employees who withhold knowledge create a vicious loop of mutual mistrust in which colleagues are reluctant to impart knowledge to one another (Cerne et al., 2014; Malik et al., 2019). In this context, ethnocentric behaviour tendencies can impede localisation success by creating obstacles like unwillingness to share knowledge among coworkers.

The impact of ethnocentric behaviour on employees' inclination to share or withhold information has implications for the organisation's ability to adapt to local circumstances, utilise local expertise, and foster the development of successful cross-cultural teams (Evelina Ascalon et al., 2008). The degree of information dissemination is a pivotal factor in influencing the effectiveness of human resource localisation endeavours. Hence, the propensity of employees to share knowledge can mediate the association between employees' ethnocentric behaviour and the achievement of human resource localisation. This mediation occurs through the influence on the extent of knowledge, skills, and expertise exchange within the organisation, involving both local and foreign employees. The deleterious impacts of ethnocentrism can be mitigated by the willingness of personnel from diverse cultural backgrounds to collaborate and share their expertise. Sharing knowledge can facilitate more effective adaptation to the local market, boost intercultural dialogue, and bolster problem-solving ability (Xia et al., 2021). An increased inclination towards the dissemination of information can enhance the achievement of localisation objectives by encouraging the integration of different cultures, facilitating the transfer of knowledge, and cultivating a work environment that is more inclusive and efficient (De Clercq & Pereira, 2020). In contrast, a lack of willingness to disseminate information can pose obstacles to the localisation process as it perpetuates cultural disparities and hampers the organisation's capacity to adjust to local circumstances. Hence, the propensity of employees to share information is of paramount importance in this association.

In the context of human resource localisation, the achievement of success may be attributed to the facilitation of knowledge exchange among employees. This is primarily accomplished by integrating local and international talent, mitigating cultural barriers, and cultivating an inclusive and efficient work environment (Ertorer et al., 2022). Conversely, individuals who possess ethnocentric perspectives may impede the exchange of information and skills with individuals from varied backgrounds, hence hindering the achievement of successful human resource localisation within culturally heterogeneous organisations. Therefore, the likelihood of employees engaging in sharing knowledge holds significant meaning inside an organisation.

Hypothesis 2

Knowledge-sharing tendency mediates the relationship between ethnocentrism and localisation success.

2.4Cultural intelligence (CQ): moderation roleIn a culturally heterogeneous work environment, employees must be able to navigate the behaviours, gestures, and assumptions that define the differences between their colleagues. Foreign cultures are ubiquitous, not only in foreign nations but also in corporate entities, professions, and regions. Interacting with the individuals within them requires sensitivity and flexibility (Kim et al., 2019). An individual with a high level of cultural intelligence demonstrates the ability to effectively and seamlessly adjust to unfamiliar environments while maintaining optimal performance without any negative consequences (Sethi et al., 2022). In their study of the impact of CQ on virtual teams' decision-making in the Middle East, Davidaviciene and Al Majzoub (2022) proposed that low CQ may result in miscommunication, diminished trust, and conflict among team members.

CQ, or cultural intelligence, is the capacity to comprehend foreign surroundings and subsequently integrate. The composition consists of three components: cognitive, physical, and emotional/motivational (Earley & Ang, 2003). Although CQ has many of the same traits as emotional intelligence, it goes a step further by allowing individuals to discern distinctive behaviour specific to the culture under consideration, those particular to certain people, and behaviours common to all individuals (Lee, 2023). According to research, not all employees are equally skilled in each of these three cultural intelligence domains, but anybody who is sufficiently vigilant, driven, and poised may develop a respectable CQ. Colleagues from different backgrounds are more likely to develop favourable connections and trust in workers with solid CQ (Afsar et al., 2021). Employees are more likely to share their expertise with people they trust; trust plays a crucial role in knowledge sharing. According to research by Ang and Van Dyne (2008), people with high CQ are more adept at fostering interpersonal trust in multicultural environments, which promotes information and skill sharing.

Employees with cultural intelligence are better able to handle communication difficulties brought on by cultural differences. Knowledge sharing requires effective communication because it guarantees that concepts and data are appropriately expressed and comprehended. Cultural intelligence is a determinant that impacts the effective adjustment to a novel cultural milieu. Individuals with cultural intelligence comprehend and value cultural diversity. Research conducted by Ang et al. (2007) has demonstrated that people with high CQ can better modify their communication style to suit a variety of audiences, making them more suitable to serve as knowledge exchange facilitators. Culturally intelligent people are more engaged with others because they have the ability to adapt to a new cultural context (Min et al., 2023).

Conflicts and misinterpretations of different cultures might prevent information from being shared in multicultural organisations. High CQ workers are better at identifying and resolving possible cultural problems, which promotes a more cooperative work atmosphere. Those with more excellent CQ are better able to keep multicultural teams free from misunderstandings and disputes (Imai & Gelfand, 2010). The benefits of cultural intelligence (CQ) serve to strengthen the impact of static intercultural competencies on dynamic intercultural competencies and adaptations. These, in turn, favourably influence the efficacy of workers' work, including their willingness to share information (Lee & Nguyen, 2019). Workers with high CQ are more accepting and considerate of different viewpoints. In a diverse workplace, employees are more inclined to participate in knowledge-sharing events when they feel appreciated and involved. It is more likely that workers with adequate CQ are more receptive to picking up tips from coworkers from diverse cultural backgrounds. Sharing of experiences and information is encouraged by this receptiveness to learning. According to Ng et al. (2009), cultural intelligence fosters cross-cultural understanding, which favours knowledge exchange in multicultural organisations.

To sum up, employees possessing a high degree of cultural intelligence are more suited to handle the intricacies of a diverse work environment, including unfamiliar cultural situations, unfriendly behavior from team members, and lousy treatment from colleagues (Chen, 2015). They excel in collaborating in multicultural teams, comprehending each member's viewpoint, and using diverse concepts, ideas, practices, and knowledge sharing to develop abilities for improving cooperation and problem-solving that boost the skill development process essential for the employee localisation process. Knowledge sharing is facilitated by their capacity to establish trust, communicate clearly, diffuse conflict, encourage inclusion, and support cross-cultural learning (Ang & Tan, 2016). As a result, high-quality information exchange among staff members fosters skill improvement and increases their capacity for resourcefulness. Thus, employee CQ plays a vital role in a multicultural work environment by increasing employee competency and reducing adverse issues that arise from cultural heterogeneity (Philip et al., 2023).

Hypothesis 3

Cultural intelligence (CQ) moderates the mediated relationship between ethnocentrism and localisation success through a knowledge-sharing tendency, such that higher CQ will weaken the indirect effect.

3Methodology3.1Sample and procedureWe conducted the initial survey in Bangladesh in July 2022. The survey involved employees from multinational companies. This research used convenience sampling to pick two foreign-owned MNC subsidiaries in Bangladesh. Both MNC- H, and Z (a pseudo name for anonymity) are information and telecommunication equipment production companies. We obtained ethics clearance from the principal authors' university to proceed with the study. The researchers conducted the initial survey and pre-tested a small group of respondents (n = 35). Examining the pre-test revealed that all of the survey's items were clear and easy to understand, with no confusing passages or sections. The questionnaire was designed in English because it is the working language of the MNCs. All of the instructions and survey items were also clear. We used a probability sampling technique to ensure that every member of the population has a chance of being selected. The HR department helped the researcher distribute the paper survey questionnaire to the staff at the office by following a simple random sampling technique. The nature of the study—its objective and voluntary, confidential character—was disclosed to the respondents in the survey invitation. Within two weeks, the respondents were expected to return the questionnaire to the researcher through the HR department. Out of a total of 450 questionnaires, 377 employees adequately returned the survey, and the response rate was 83.77 %. Out of the 377 survey responses that were returned, 361 appeared to be complete after 16 incomplete responses were eliminated. We conducted Slovin's test for sample adequacy and found that 248 should be the adequate sample size. So, we retained 361 samples for further analysis. The final study sample demographics were as follows: the mean age of participants was 29.71 (sd-6.65), the mean of gender was 1.24 (sd-0.427, male 76.1 % & female 23.9 %), the mean of employee type was 1.19, SD- 0.39 (Local 81.2 % & Foreign 18.2 %) and the mean of work experience was 6.36 (sd-5.11).

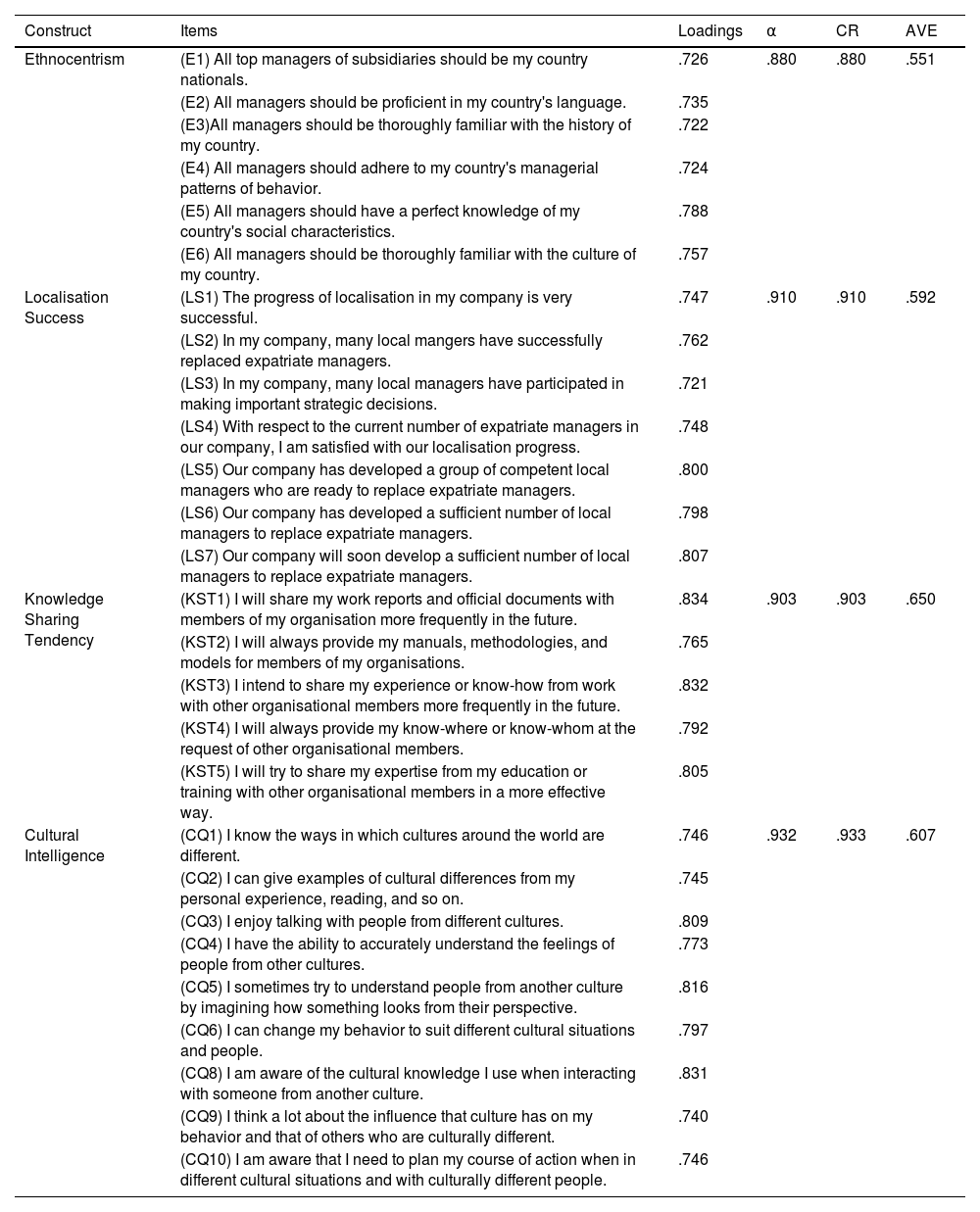

3.2Instrument developmentThis study used Likert scales to collect data from the respondents. We have adopted the questionnaire other researchers created, validated, and used (See Appendix 1).

3.2.1Ethnocentrism (Ethno)This study used Zeira's (1979) Likert-type scale to measure employee ethnocentrism. The questionnaire includes six items. Items included "All top managers of subsidiaries should be my country nationals". Respondents were asked to respond on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The internal consistency for this scale in this study was α = 0.880.

3.2.2Localisation success (LS)A seven-item Likert-type scale developed by Law et al. (2009) was used to measure localisation success. Items included "The progress of localisation in my company is very successful.". The respondents were assessed on a five-item Likert scale ranging from (1= Strongly agree to 5= Strongly disagree). The internal consistency for this scale in this study was α = 0.910.

3.2.3knowledge-sharing tendency (KST)The Bock et al. (2005) five-item Likert-type scale was used to measure Coworker knowledge-sharing tendency. Items included "I will share my work reports and official documents with members of my organisation more frequently in the future". The participants' responses on a Likert-type scale ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The internal consistency for this scale in this study was α = 0. 903.

3.2.4Cultural intelligence (CQ)The Thomas et al. (2015) 10-item scale was used to evaluate the cultural intelligence CQ of employees. Items included "I am aware that I need to plan my course of action when in different cultural situations and with culturally different people". Respondents were assessed on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all to 5 = Extremely well). The internal consistency for this scale in this study was α = 0.932

Demographic variables, age, gender (1- male, 2- female), years of work experience ("Tenure"), and employee type (1- Local, 2- Foreign) were controlled in this research.

3.3Statistical analysisThis study used IBM SPSS v.26 and AMOS V.26 for descriptive analysis and correlations of variables. In the Hayes-developed PROCESS Marco V4.0 in SPSS, Model 4 was used to evaluate the mediation model, and Model 14 was used to assess the moderated mediation model (Hayes, 2017). First, the independent variable (Ethnocentrism), dependent variable (localisation success), and mediator (Knowledge sharing tendency) were used in the mediation studies. The bootstrapping method for measuring indirect impact was used to determine the best test of mediation effect, and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were determined. There were 5000 bootstrap samples. Second, a test was conducted on the moderated mediation effects using a moderator (cultural intelligence).

The moderated mediation effect can be found in the substantial interaction coefficient between cultural intelligence and knowledge-sharing tendency. The moderating influence of cultural intelligence was demonstrated by looking at the conditional effects at one standard deviation (SD) above and below the mean. This investigation looked at whether there was a significant difference between the slopes of the regression equations for high and low values of cultural intelligence. As covariates, control factors, including age, gender, job experience, and employee type, were added to the model. At the 5 % significance level, there was no significant mediating (indirect) impact if the confidence interval contained zero. After applying mean centring to the moderating and independent variables, multicollinearity was reduced, and the same analysis was carried out.

4Results4.1Descriptive statistics and correlationsTable 1 shows the study variables' mean, standard deviation, and correlations. According to the table, the mean and standard deviation of Age (M = 29.71, SD=6.65), Gender (M = 1.24, SD=0.427), Years of Work Experience (M = 6.36, SD=5.11), Employee type (M = 1.19, SD=0.39), ethnocentrism (M = 1.87, SD=0.78), localisation success (M = 4.23, SD=0.73), knowledge-sharing tendency (M = 4.24, SD=0.86), and cultural intelligence (M = 4.16, SD=0.78). The Table 1 also shows the correlations, ethnocentrism negatively and significantly correlates to localisation success (r=−0.705, p < .01). The correlations were also significant between ethnocentrism and knowledge-sharing tendency (r=−0.646, p < .01) and Cultural Intelligence (r=−0.658, p < .01). The relationship between knowledge-sharing tendency and localization success is positive and significant (r = 0.795, p < .01). In addition, cultural intelligence is positively and significantly related to Knowledge sharing tendency (r = 0.659, p < .01) and localisation success (r = 0.833, p < .01). Thus, the correlation among study variables shows initial support for the proposed hypothesis.

Means, Standard deviations, and inter-item correlations.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 29.71 | 6.65 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Gender | 1.24 | .427 | −0.096 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Years of Work Experience | 6.36 | 5.11 | .869⁎⁎ | −0.085 | 1 | |||||

| 4. Employee type | 1.19 | .39 | −0.045 | .063 | −0.083 | 1 | ||||

| 5. Ethnocentrism | 1.87 | .78 | .072 | −0.027 | .138⁎⁎ | −0.037 | 1 | |||

| 6. Localisation Success | 4.23 | .73 | −0.027 | −0.024 | −0.088 | .039 | −0.705⁎⁎ | 1 | ||

| 7. Knowledge-sharing Sharing Tendency | 4.24 | .86 | −0.029 | −0.032 | −0.075 | .041 | −0.646⁎⁎ | .795⁎⁎ | 1 | |

| 8. Cultural Intelligence | 4.16 | .78 | −0.018 | −0.018 | −0.075 | .044 | −0.658⁎⁎ | .833⁎⁎ | .659⁎⁎ | 1 |

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the measurement model. Table 2 shows the result of the CFA of all four models. Item CQ7 was removed due to low factor loading (0.60) from cultural intelligence and cross-loading with localisation success (LS); thus, a total of 9 items were used to measure cultural intelligence (CQ). The results of the hypothesised four-factor model (X2=831.24, df=318, X2/df=2.61, CFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.915, RMSEA=0.067) were the most fit compared to the other three models, thus ensuring the construct validity of our measurement model. Therefore, we retained the four-factor model for further analysis.

4.3Reliability and validity analysisThe results from Table 3 show Cronbach's alpha value ranged from 0.880 to 0.932, which is greater than the cut-off value of 0.707, suggesting that the scales are reliable (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). In addition, table 3 shows that the composite reliability (CR) values are all above the threshold value of 0.70, endorsed reliability (Hair et al., 2010). Furthermore, Table 3 shows the values of Average Variance extracted AVE, and all the values are above the cut-off point of 0.50, ensuring convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Reliability and convergent validity.

| Construct | Items | Loadings | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnocentrism | (E1) All top managers of subsidiaries should be my country nationals. | .726 | .880 | .880 | .551 |

| (E2) All managers should be proficient in my country's language. | .735 | ||||

| (E3)All managers should be thoroughly familiar with the history of my country. | .722 | ||||

| (E4) All managers should adhere to my country's managerial patterns of behavior. | .724 | ||||

| (E5) All managers should have a perfect knowledge of my country's social characteristics. | .788 | ||||

| (E6) All managers should be thoroughly familiar with the culture of my country. | .757 | ||||

| Localisation Success | (LS1) The progress of localisation in my company is very successful. | .747 | .910 | .910 | .592 |

| (LS2) In my company, many local mangers have successfully replaced expatriate managers. | .762 | ||||

| (LS3) In my company, many local managers have participated in making important strategic decisions. | .721 | ||||

| (LS4) With respect to the current number of expatriate managers in our company, I am satisfied with our localisation progress. | .748 | ||||

| (LS5) Our company has developed a group of competent local managers who are ready to replace expatriate managers. | .800 | ||||

| (LS6) Our company has developed a sufficient number of local managers to replace expatriate managers. | .798 | ||||

| (LS7) Our company will soon develop a sufficient number of local managers to replace expatriate managers. | .807 | ||||

| Knowledge Sharing Tendency | (KST1) I will share my work reports and official documents with members of my organisation more frequently in the future. | .834 | .903 | .903 | .650 |

| (KST2) I will always provide my manuals, methodologies, and models for members of my organisations. | .765 | ||||

| (KST3) I intend to share my experience or know-how from work with other organisational members more frequently in the future. | .832 | ||||

| (KST4) I will always provide my know-where or know-whom at the request of other organisational members. | .792 | ||||

| (KST5) I will try to share my expertise from my education or training with other organisational members in a more effective way. | .805 | ||||

| Cultural Intelligence | (CQ1) I know the ways in which cultures around the world are different. | .746 | .932 | .933 | .607 |

| (CQ2) I can give examples of cultural differences from my personal experience, reading, and so on. | .745 | ||||

| (CQ3) I enjoy talking with people from different cultures. | .809 | ||||

| (CQ4) I have the ability to accurately understand the feelings of people from other cultures. | .773 | ||||

| (CQ5) I sometimes try to understand people from another culture by imagining how something looks from their perspective. | .816 | ||||

| (CQ6) I can change my behavior to suit different cultural situations and people. | .797 | ||||

| (CQ8) I am aware of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with someone from another culture. | .831 | ||||

| (CQ9) I think a lot about the influence that culture has on my behavior and that of others who are culturally different. | .740 | ||||

| (CQ10) I am aware that I need to plan my course of action when in different cultural situations and with culturally different people. | .746 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

We checked the discriminant validity of the scales in the study through the Fornell & Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). According to the Fornell and Larcker (1981) Criterion, the square root of the average variance extracted by a construct must be greater than the correlation between the construct and any other construct. From Table 4, all the correlation values are lower than the square root of AVE, which shows discriminant validity. We further inspected discriminant validity through the HTMT ratio (Hair et al., 2017). Table 4 shows the outcome of all ratios less than 0.85, thus confirming discriminant validity.

4.5Common method biasCommon Method Bias (CMB) is a significant issue that has the potential to compromise the dependability of study findings. Our study may have common method bias because we used a self-report questionnaire to get data from the same source. To mitigate the incidence of CMB, we implemented ex-ante and ex-post methodologies as described by Podsakoff et al. (2003). We implemented several methods for ex-ante operations, mostly consisting of the following steps: (1) The participants were provided with information regarding the objective of data collection, the intended use of the data, the non-commercial nature of the study, and the confidentiality of the questionnaire prior to their participation in the questionnaire survey. (2) The participants were notified of their entitlement to withdraw from the data gathering process at any given moment. (3) The study included anonymous questionnaires, so participants were not obligated to furnish their names or contact details. (4) We explicitly stated that there were no correct or incorrect answers, in order to motivate participants to provide the most truthful responses. In addition, the number of questions was deliberately limited to prevent the responders from experiencing boredom and impatience.

As for ex-post remedies, we evaluated the possible issues with Harman's single-factor analysis for each item (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). We carried out a variety of tests to make sure that our data did not include common method variance (CMV). Harman's (1960) one-factor test resulted in a factor that accounted for just 44.23 % of the variance, showing that CMB is not an issue since it falls below the 50 % threshold. Furthermore, according to Table 5, the single-factor CFA analysis values of CFI = 0.704, TLI = 0.679, NFI=0.672, are significantly less than the cut-off value of 0.90, and RMSEA=0.130, which is higher than the cut-off value of 0.08. Thus, the test values did not produce an acceptable fit with the data, the absence of common technique bias was confirmed. Moreover, we conducted a multicollinearity test between the variables using the complete variance inflation factor (VIF) statistics. If the VIF value is less than 2.5, multicollinearity worries should be allayed (Johnston, 2018). The result of Table 5 showed that all VIF values ranged from 2.05 to 2.11. In order to reduce worries about multicollinearity, the tolerance values should be larger than 0.30, and the analysis reveals that all of the tolerance values varied from 0.473 to 0.487. Thus, the above findings verified that common technique bias did not exist in our study.

4.6Hypothesis testingFirst, we tested the relationship between ethnocentrism, knowledge-sharing tendency, and localisation success. Hayes PROCESS v4.0 model- 4 was used to check the mediating effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success through knowledge sharing tendency. Table 6 shows ethnocentrism is negatively and significantly associated with localisation success (β = −0.3058, p < .001), which supports hypothesis 1. Ethnocentrism also negatively and significantly predicts knowledge-sharing tendency (β = −0.717, p < .001). The knowledge-sharing tendency is positively and significantly associated with localisation success (β = 0.4907, p < .001). Table 7, the bootstrapping result also shows that the direct effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success is significant (β = −0.3058, p < .001, CI=−0.3771 to −0.2345), and the confidence interval does not encompass zero. The indirect effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success through knowledge-sharing tendency is significant at (β = −0.3516, p < .001, CI=−0.4385 to −0.2562), and the confidence interval does not encompass zero; thus, knowledge-sharing tendency significantly and partially mediates the relationship between ethnocentrism and localisation success which support hypothesis 2. The total effect of ethnocentrism on localisation is also significant (β = −0.6573, p < .001, CI=−0.7273 to −0.5874), and the confidence interval does not encompass zero. Table 6 also shows that age, gender, tenure, and employee type are insignificant. The variance in the localisation success by independent variable indicator R2 =0.6957 and F = 134.90 is significant at p < .001 level.

Regression result.

| KST | LS | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCl | β | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI |

| Ethno | −0.717 | .045 | −15.80 | .0000 | −0.8057 | −0.6273 | −0.3058 | .0363 | −8.4314 | .0000 | −0.3771 | −0.2345 |

| KST | .4907 | .0325 | 15.0872 | .0000 | .4267 | .5546 | ||||||

| Age | .0019 | .0107 | .1730 | .8628 | −0.0192 | .0229 | .0055 | .0066 | .8460 | .3981 | −0.0074 | .0184 |

| Gender | −0.1007 | .0825 | −1.2208 | .2230 | −0.2628 | .0615 | −0.0222 | .0506 | −0.4383 | .6614 | −0.1218 | .0774 |

| Tenure | .0000 | .0141 | .0004 | .9997 | −0.0276 | .0276 | −0.0063 | .0086 | −0.7290 | .4665 | −0.0232 | .0107 |

| Employee type | .0454 | .0899 | .5052 | .6137 | −0.1313 | .2221 | .0038 | .0551 | .0699 | .9443 | −0.1045 | .1122 |

| R2 | .4206 | .6957 | ||||||||||

| F | 51.55⁎⁎⁎ | 134.90⁎⁎⁎ |

We used Hayes PROCESS v4.0 model- 14 to check whether cultural intelligence moderates the mediated relationship between knowledge-sharing tendency and localisation success. As shown in Table 8, after controlling the covariates, ethnocentrism negatively affects knowledge-sharing tendency (β = −0.7165, p < .001). In addition, ethnocentrism negatively affects localisation success ((β = −0.1050, p < .001) and knowledge sharing tendency positively and significantly affects localisation success (β = 0.2788, p < .001). Cultural intelligence positively affects localisation success (β = 0.4017, p < .001). Cultural intelligence negatively and significantly affects employees with a low knowledge-sharing tendency (−0.0638, p < .001) on localisation success. Fig. 2, simple slope shows that the effect of low knowledge-sharing tendency on localisation success gets weaker with an increase in CQ. The variance in the localisation success predicted by independent variables indicator R2 = 0.8170, F = 196.43, which is significant at p < .001 level. Table 8 also shows that age, gender, tenure, and employee type are insignificant.

Testing the moderated mediation effects of ethnocentrism on localisation success.

| KST | LS | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCl | β | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI |

| Ethno | −0.7165 | .0454 | −15.7987 | .0000 | −0.8057 | −0.6273 | −0.1050 | .0312 | −3.3638 | .0009 | −0.1664 | −0.0436 |

| KST | .2788 | .0305 | 9.1419 | .0000 | .2188 | .3388 | ||||||

| CQ | .4017 | .0357 | 11.2481 | .0000 | .3315 | .4719 | ||||||

| Interaction | −0.0638 | .0186 | −3.4342 | .0007 | −0.1004 | −0.0273 | ||||||

| Age | .0019 | .0107 | .1730 | .8628 | −0.0192 | .0229 | .0030 | .0051 | .5808 | .5617 | −0.0071 | .0130 |

| Gender | −0.1007 | .0825 | −1.2208 | .2230 | −0.2628 | .0615 | −0.0440 | .0394 | −1.1157 | .2653 | −0.1216 | .0336 |

| Tenure | .0000 | .0141 | .0004 | .9997 | −0.0276 | 0276 | −0.0029 | .0067 | −0.4396 | .6605 | −0.0161 | .0102 |

| Employee type | .0454 | .0899 | .5052 | .6137 | −0.1313 | .2221 | −0.0078 | .0428 | −0.1809 | .8566 | −0.0920 | .0765 |

| R2 | .4206 | .8170 | ||||||||||

| F | 51.55⁎⁎⁎ | 196.43⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||||

Table 9 shows the conditional indirect effect of Ethnocentrism on Localization success at different CQ levels. The standardised regression coefficient of the mediating effect of Knowledge-sharing tendency was −0.2355 at the lower level of employee cultural intelligence, decreased to −0.1998 at the medium level, and decreased to −0.1640 at the higher level of employee cultural intelligence (CQ). The difference index was 0.0457, and the 95 % confidence interval was [0080, 0887], which did not encompass zero. Therefore, cultural intelligence (CQ) moderated the effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success through knowledge sharing tendency, and the negative impact of ethnocentrism gets weaker when an employee has a high level of cultural intelligence (CQ). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

5Discussion and conclusionsThe results of the current study highlight the influence of employee ethnocentric behaviour on human resource localisation success, either directly or indirectly, through the mediation of employee knowledge-sharing tendency and the moderated mediation of cultural intelligence Fig. 1.

The analysis result Table 6 shows that ethnocentrism negatively predicts human resource localisation success (Hypothesis 1). This is because exhibiting ethnocentrism may display a reduced propensity to trust or engage in collaborative efforts with colleagues with diverse cultural backgrounds. Since ethnocentric workers tend to think that others are different and inferior (Bizumic, 2015), after all, they come from different cultures, including country, gender, race, religion, educational background, and prior work experience. A rise in cross-border migration will hasten workplace diversity at multinational corporations, which in turns will increase team diversity. The lack of trust within a team can harm the team members' willingness to communicate openly and share expertise (Cvitanovic et al., 2021). This is due to the apprehension that their ideas may not be adequately appreciated or regarded. Lack of cooperation or unhealthy competition among team members can negatively affect the positive impact of innovation efficiency (Huang, 2023). Ethnocentric persons tend to prefer those who belong to their own cultural or ethnic group (Bizumic et al., 2021). The practice of favouritism has the potential to result in the marginalisation of individuals from diverse backgrounds, engendering feelings of alienation and reducing their inclination to contribute their expertise to the prevailing cultural majority. Therefore, this behavioural tendency exhibited by workers has the potential to generate or amplify in-group favouritism (Pettigrew, 2005). This phenomenon can potentially perpetuate and strengthen preconceived notions and discriminatory attitudes against individuals of diverse professional backgrounds. These prejudices can potentially foster a hostile or unwelcoming atmosphere for employees from varied backgrounds, dissuading them from actively contributing their expertise or personal experiences. According to a study conducted by Bizumic and Duckitt (2008), ethnocentrism may be seen as a manifestation of group-level narcissism. The researchers further propose that individuals with narcissistic tendencies tend to exhibit self-centred and exploitative attitudes, even within their own social groupings, so ethnocentrism can also harm personnel within the in-group. This severely affects human resource management in geographically detached subsidiaries (Michailova et al., 2017). But efficient collaboration is crucial for multinational enterprises because different HR systems result from particular disparities in the historical, cultural, and institutional history of various nations (Brewster et al., 2016; Farndale et al., 2017; Cooke et al., 2020). According to Law et al. (2009) and Potter (1989), localisation is the extent to which expatriate employees are replaced by host country employees originally held by expatriate employees. The expatriate employees in the MNCs are the employees sent from the parent country or third country to the host country subsidiary. Local employees or host country employees in multinational firms are the employees recruited from the local labour market of the host country. Localisation refers to a procedural approach wherein personnel at the local level augment their skill sets, hence leading to an improvement in their overall performance. The primary objective is to provide training and development opportunities for local individuals, enabling them to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively replace expats in a competent and efficient manner (Bhanugopan & Fish, 2007). In essence, the presence of ethnocentric behaviour poses significant obstacles for organisations in their efforts to efficiently manage and harness the potential of diversity. This phenomenon can lead to the overlooking of prospective possibilities and the inability to fully utilise the vast capabilities of a workforce characterised by diversity. Localisation success is not just replacing expatriate employees with local employees; instead, it is replacing expatriates with competent local employees who can perform the same as expatriate employees (Jain et al., 2015). Thus, the achievement of human resource localisation success is contingent upon effective collaboration among workers and the cultivation of skill development and competency. Employee ethnocentric behaviour obstructs their interaction, hindering human resource localisation success.

With the presence of knowledge sharing, the effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success is reduced (Table 7). Thus, employee knowledge-sharing tendencies partially mediate the relationship between ethnocentrism and localisation success (Hypothesis 2). The study result also shows that ethnocentrism reduces employee knowledge-sharing tendencies (Path_a). Because ethnocentric behaviours have the potential to give rise to linguistic and communication obstacles, the flow of practical knowledge and ideas may be hindered when employees are less willing to communicate with colleagues who do not possess a shared cultural background, which might limit one's cultural/scientific knowledge (Keith, 2019). The exchange of knowledge is a critical factor in fostering innovation within an organisational context (Azeem et al., 2021). The restriction of information flow, ideas, and the lack of intercultural communication due to ethnocentrism hampers the process of creativity and the advancement of innovative problem-solving approaches (Gonçalves et al., 2020). In a company characterised by rampant ethnocentrism, the resulting toxic organisational culture might impede the success of employee knowledge-sharing and skill-improvement efforts. Concerning the above notion, it is evident that ethnocentric behaviour severely hampers the free flow of knowledge sharing among employees at the workplace. When knowledge-sharing is dropped among employees, localisation success also shrinks; this affects localisation success because knowledge-sharing tendency and employee localisation success are positively correlated (Path_b).

The study results further showed that culturally astute professionals within multinational corporations frequently tend to disseminate knowledge among their peers within the professional environment (Hypothesis 3). These findings also aligned with the findings of Stoermer et al. (2021). The conditional indirect effect (Table 9) demonstrates that the higher degree of CQ reduces the negative indirect effect of ethnocentrism on localisation success. The possible reason is that cross-cultural intelligence (CQ) allows individuals to get a broader perspective by transcending their own cultural biases and assumptions (Earley, 2002). The act of sharing knowledge fosters a sense of teamwork among team members who possess diverse cultural backgrounds. Incorporating varied viewpoints and experiences can potentially boost the generation of creative solutions and ideas (Tang et al., 2020). Employees sharing their skills and ideas can enhance team performance, fostering intellectual curiosity and cultivating a culture of ongoing learning inside the organisation (Fang et al., 2018). When individuals with CQ possess the awareness that a team equipped with comprehensive knowledge and expertise is more inclined to achieve favourable outcomes, they actively contribute to attaining such accomplishments (Berraies, 2020). Multinational corporations commonly consist of a diverse workforce comprising individuals from a multitude of ethnic backgrounds (Park, 2020). The act of sharing information fosters the development of an inclusive atmosphere whereby the contributions of all individuals are esteemed, and a variety of viewpoints are included in the decision-making procedures. Employees who possess cultural intelligence demonstrate an understanding of the significance of cultural competency (Setti et al., 2022). The dissemination of knowledge pertaining to diverse cultures, customs, and communication styles can enhance the ability of individuals to negotiate cross-cultural encounters with more efficacies. In the midst of intricate issues, the act of information exchange can yield novel perspectives and alternate methodologies. Employees with cultural intelligence recognise varied viewpoints' significant value in facilitating efficient problem-solving. CQ promotes positive cross-cultural relations (Presbitero, 2021). Culturally intelligent individuals frequently acknowledge that the act of information sharing may significantly help their career advancement (Ratasuk & Charoensukmongkol, 2020). Participation in this endeavour has the potential to provide mentorship, foster leadership responsibilities, and get acknowledgement within the organisational context. In essence, personnel with a high level of cultural intelligence within multinational corporations possess a comprehensive understanding of the advantages associated with information sharing. This understanding extends beyond the organisational realm and encompasses their own personal and professional development as high CQ employees are more committed to the organisation (Zhang et al., 2022). It is acknowledged that sharing information plays a crucial role in fostering diversity, inclusiveness, cooperation, and overall achievement within a global corporate context. Thus, CQ weakens the negative effect of ethnocentrism on knowledge-sharing tendency, and employees with higher CQ and knowledge-sharing tendency positively and significantly contribute to human resource localisation success.

5.1Theoretical implicationsThe study's findings have significant theoretical ramifications for future research in the field of international human resource management on ethnocentrism and the efficacy of human resource localisation in multicultural workplaces. First, our findings provide novel insights since ethnocentrism and localisation success through the intervention of employee's knowledge-sharing tendencies have not been previously investigated. Consequently, future studies looking into the ethnocentric behavior of employees and the effectiveness of localisation in MNC subsidiaries may find a use for our findings. Second, based on our analysis of the literature and the published findings, the model put out in this study may be expanded in further investigations. Thirdly, this research adds to the body of knowledge on employee ethnocentric behavior by offering a more thorough understanding of the effectiveness of human resource localisation. The study's specific findings serve as a valuable reference point for anyone interested in a multicultural workplace.

5.2Managerial implicationsThis work contributes to improving the management of employee ethnocentrism in multicultural workplaces. Managers can take steps to reduce worker's ethnocentric behavior at the office. Employees can be given cross-cultural training to understand the cultural differences among different nations. This research also helps to understand the importance of cultural intelligence in employees. Recruiting culturally intelligent employees will help managers reduce cross-cultural class differences among coworkers. Cultural intelligence will also help to mitigate employee's ethnocentric behavior; thus, recruiting and retaining culturally intelligent workers at the workplace is crucial for MNCs.

This study also helps MNC managers to understand the obstructers of human resources localisation success. Reducing those obstacles will boost the localisation process. Human resource localisation success is crucial for MNCs because employing locals is cost-effective, whereas employing expatriates might cost twice as much as local employees. Costs associated with expatriates who return early are very high for the organisations that are employed. Another cause is the worry that expatriates will find it difficult to make friends in their new country. Executives returning from abroad often run into difficulties integrating into their new companies' cultures and learning about the local market. Political and ethical concerns have also been found to be essential drivers of worker localisation (Harry, 2007). Thus, localisation success is advantageous for any multinational company, and the disruption of human resource localisation success will hamper the organisation's growth. Mitigating ethnocentrism in the workplace will accelerate localisation success. As a result, recognising and challenging ethnocentrism is essential to promote cultural understanding, tolerance, and peaceful coexistence in our increasingly interconnected world. Adopting the principle of cultural relativism is endeavouring to comprehend and value cultural distinctions without imposing personal judgements, which can help counteract the adverse effects of ethnocentrism.

Finally, this study finding encourages multicultural organisations to take the initiative to promote skill transfer and knowledge sharing among employees. Knowledge hiding or knowledge not sharing has an adverse effect on the human resource localisation process. This condition is especially harmful in the context of localisation when collaboration across different cultures and mutual comprehension is of utmost importance. The process of transferring information becomes difficult, as workers who are ethnocentric are less inclined to dedicate time to sharing valuable ideas and experiences that might be advantageous for the localisation process. Knowledge dissemination inside a business is crucial for promoting innovation, improving productivity, and sustaining a competitive advantage. It entails the sharing of knowledge, abilities, and specialised knowledge among staff members, thereby fostering a culture of ongoing learning and development. MNCs should take initiatives to reduce cultural barriers in the workplace, which, in turn, promotes interaction and knowledge sharing among employees and ultimately contributes to the human resource localisation process.

5.3Limitations and future researchIn contrast to other studies, the present research exhibits several limitations. The potential for increased saturation in the outcome may be realised with the inclusion of data from a broader range of nations. This research follows a quantitative approach, which tends to reduce intricate phenomena by converting them into quantifiable variables, sometimes resulting in oversimplification and the omission of subtle nuances. The representation may not fully encompass the depth and complexity of human experiences or the circumstances in which behaviours and attitudes manifest. The present study relies on cross-sectional data, which has limitations in capturing dynamic changes and trends over time. Therefore, future researchers may consider employing longitudinal studies to comprehensively understand the changes that occur after identifying ethnocentric employees and providing them with cultural sensitivity training. Integrating both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies in a mixed-methods approach can enhance the comprehensiveness of understanding in this particular study area, hence addressing certain constraints. Future research can also replicate this study where cultural distance is high. Countries with high cultural distance might give interesting findings.

Furthermore, potential researchers can include the cultural characteristics of the MNCs in the research framework to extend this research. Its dynamic nature characterises the management style of MNCs, since it undergoes fast evolution in both practices and ideas. Empirical research may rapidly become obsolete when new trends arise, and organisational environments evolve. Hence, it is recommended that future studies should take into account this matter.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMehedi Hasan Khan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jiafei Jin: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

| Construct | Items | Author (S) |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnocentrism | (E1) All top managers of subsidiaries should be my country nationals.(E2) All managers should be proficient in my country's language.(E3)All managers should be thoroughly familiar with the history of my country.(E4) All managers should adhere to my country's managerial patterns of behavior.(E5) All managers should have a perfect knowledge of my country's social characteristics.(E6) All managers should be thoroughly familiar with the culture of my country. | Zeira's (1979) |

| Localisation Success | (LS1) The progress of localisation in my company is very successful.(LS2) In my company, many local mangers have successfully replaced expatriate managers.(LS3) In my company, many local managers have participated in making important strategic decisions.(LS4) With respect to the current number of expatriate managers in our company, I am satisfied with our localisation progress.(LS5) Our company has developed a group of competent local managers who are ready to replace expatriate managers.(LS6) Our company has developed a sufficient number of local managers to replace expatriate managers.(LS7) Our company will soon develop a sufficient number of local managers to replace expatriate managers. | Law et al. (2009) |

| Knowledge Sharing Tendency | (KST1) I will share my work reports and official documents with members of my organisation more frequently in the future.(KST2) I will always provide my manuals, methodologies, and models for members of my organisations.(KST3) I intend to share my experience or know-how from work with other organisational members more frequently in the future.(KST4) I will always provide my know-where or know-whom at the request of other organisational members.(KST5) I will try to share my expertise from my education or training with other organisational members in a more effective way. | Bock et al. (2005) |

| Cultural Intelligence- CQ | (CQ1) I know the ways in which cultures around the world are different.(CQ2) I can give examples of cultural differences from my personal experience, reading, and so on.(CQ3) I enjoy talking with people from different cultures.(CQ4) I have the ability to accurately understand the feelings of people from other cultures.(CQ5) I sometimes try to understand people from another culture by imagining how something looks from their perspective.(CQ6) I can change my behavior to suit different cultural situations and people.(CQ7) I accept delays without becoming upset when in different cultural situations and with culturally different people.(CQ8) I am aware of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with someone from another culture.(CQ9) I think a lot about the influence that culture has on my behavior and that of others who are culturally different.(CQ10) I am aware that I need to plan my course of action when in different cultural situations and with culturally different people. | Thomas et al. (2015) |