the main objective of this article is to check whether the relationship between corporate social responsibility activities and employee commitment is mediated by the existence of two other attitudinal variables of workers: intrinsic motivation and trust towards the organisation.

Design/methodology/approacha survey of 318 Ecuadorian workers provides data that allows the application of structural equation modelling to verify the existence of such relationships.

Findingsthe work shows a positive and significant relationship between CSR actions and the two attitudes of the employees considered: trust and intrinsic motivation. Furthermore, the mediating character that both variables play in the relationship between CSR and organisational commitment is confirmed. Ecuadorian managers can infer from this study the positive effects that CSR practices have on various attitudes and behaviors of employees, such as their motivation at work, their confidence in the company and their commitment to it.

Research limitations/implicationsthe scant generalisation of its results to the Ecuadorian reality given that the firms are located in a single zone of the country and belong to a specific activity.

Practical implicationsnew determinant factors of the relations between the endogenous and exogenous variables could be included.

Social implicationsthe consideration of other variables which could condition the relations studies: sex, age, etc.

Originality/valuethe work increases the already existing knowledge about the relationship between CSR and different attitudes and behaviours of employees within formal work organisations.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has evolved in the complex and modern business environment from being a link with activities related to philanthropy to its consideration as an innovative management paradigm in organisations which generates profits not only for the firm but also for society.

Prolonged discussions have been held over time about the role of CSR, seen predominantly from opposing approaches: that of Freeman, on the favourable side, and that of Friedman, in contrast. Milton Friedman's position is clear: firms must maximise profit for their shareholders and this aim is their unique social responsibility. On the other hand, Freeman adopts a more global approach and argues that an organisation must satisfy various stakeholder groups, including its employees, the government and society, beyond the satisfaction of the shareholders, seeking legitimacy and recognition in society. Currently, CSR represents a strategic value for companies, as it can bring internal and external benefits. Internal benefits through the development of new resources and capabilities, mainly associated with the knowledge and corporate culture transmitted to employees. And external benefits related to the effects on the corporate reputation of organisations, whose disclosure and accountability for the social consequences of their activities can improve relations with external stakeholders, attract qualified human resources and increase the motivation, morale, commitment and loyalty of current employees within and to the company, and attract considerable publicity. CSR has therefore become a necessary priority for the leaders of organisations worldwide (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006; Porter & Kramer, 2006). This means the day-to-day incorporation of social and political trends within organisations’ corporate strategy. Their implementation is essential to achieve success in the face of the competition (Reich, 2007) and can be understood as a strategic investment (McWilliams, Siegel & Wright, 2006).

According to Bakan (2004) and Werther & Chandler (2005), CSR is a determining factor for the development of international business. This is especially so when the global brands of multinational companies are supported by competitive strategies in adopting CSR practices, in response to the changing expectations of stakeholders. These are a result of the complex social, economic, technological, cultural and political changes occurring in the world. This adopting of CSR practices becomes a means for redefining profit maximisation in favour of all the companies’ stakeholders, generating commitment in the members of the organisation, building brand reputation and positioning management to best optimise long-term shareholder returns. Likewise, in the international context, based on work within institutions such as the United Nations (UN), the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and, recently, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the role of multinational companies as part of the social fabric of nations has been highlighted, and they are considered key influencers in the adoption of business management models focused on aspects such as the globalisation of markets, increasing the educational level of workers and the population, trade liberalisation, sustainable environmental development and ethics in governance. There has also been the effect of the multiplication and dissemination of indices and rules whose primary objective, as expressed by Valenzuela, Jara & Villegas (2015), is to establish standards that disseminate information about companies with respect to their CSR practices.

According to what was stated by Sánchez & Puente (2017), at the level of international and European institutions “common elements have been established as general principles of CSR, such as: voluntarism, aggregated value, integration and efficiency, adaptability and flexibility, credibility, globality, the social dimension and nature, environmental aspects, and the involvement and participation of the stakeholders…where workers and their union organisations are formed apart from the global decisions of the firm and the actions that this carries out in all its parameters” (p. 67). CSR must have an integrated approach within organisations, with the participation and consensus of the members of the organisation, for the purpose of collaborating in the generating of a competitive advantage for firms (Cohen, 2010). Manimegalai & Baral (2018) argue that if the CSR actions are correctly directed through the appropriate and available means, they can influence the positive attitudes of employees (an organisation's most valuable asset).

Yu & Choi (2014) spotlight the scant interest that the studies centred on the effects of CSR practices have granted to employees as internal stakeholders. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out in this sense that there are works such as those of Pinnington, Macklin & Campbell (2007) and Boddy, Ladyshewsky & Gavin (2010).

This article means to contribute a grain of sand to the state of the research about the effects of CSR on employees. To do so, the following aims are sought: to establish the degree of influence of CSR practices on workers’ internal motivation and trust; to determine the influence of these two variables on the commitment of employees; and, finally, test whether the influence of CSR on employee engagement is mediated by the other two variables, intrinsic motivation and organisational trust.

To attain these goals, this article is organised as follows. Firstly, the proposed model and its hypotheses are presented, based on a literature review. Next, the methodology used and the results obtained are set out. Finally, the main conclusions and the limitations of the work are put forward.

2PROPOSAL AND JUSTIFICATION OF THE MODEL2.1CSR and internal motivationThe typical CSR initiatives in a firm significantly affect the behaviour of the employees within it, they become a priority stakeholder in the CSR field. This approach has been interpreted as the way in which the perception and response of workers to the CSR activities of their organisation can yield positive results in the workplace (Rupp & Mallory, 2015; Shen & Benson, 2016; Vlachos, Panagopoulos, Bachrach & Morgeson, 2017).

Although establishing the causes of human motivation is complex, the hierarchy of needs investigated by Maslow was a first approach to determine it, integrating a broad perspective of motivation. It argued that this has the following hierarchy: 1) physiological needs, 2) safety needs, 3) belonging and love needs, 4) esteem needs, 5) self-actualisation needs, and, lastly, 6) a wish to know and understand, that is to say, cognitive impulses. As Fırat, Kılınç, & Yüzer (2018) point out, motivation is the energy that drives a person towards a certain goal and, in the words of Ryan & Deci (2020), it is essentially based on three needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness.

Employee motivation does not depend only on the need for a financial stimulus (money), as non-financial stimuli are important too for workers. Authors such as Basil & Weber (2006) and Collier & Esteban (2007) point out the relevance of CSR activities to capitalise on many opportunities lost within the management of human resources. From the point of view of the theory of self-determination, the existence of two types of incentives which influence employee motivation is noted: the external and the internal. Minbaeva's (2008) study remarks that external motivation keeps a person in the job, whilst internal motivation is indispensable to incentivise a greater performance.

Intrinsic motivation is defined as “doing something because it is enjoyable, optimally challenging, or aesthetically pleasing” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 72). In this sense, the intrinsic motivation construct is related with facing challenges, enjoying the task entrusted and carried out, feeling achievements, receiving positive appreciation and recognition, being treated respectfully, getting feedback, and taking part in decision making (Gheitani, Imani, Seyyedamiri & Foroudi, 2019; Mosley, Megginson & Pietri, 2005; Mullins, 2006; Greenberg & Baron, 2008).

The first research on the relation between CSR activities and the motivation of employees is the work of Skudiene & Auruskeviciene (2012). In a sample of 274 Lithuanian employees, they find positive and significant relations between CSR and the employees’ intrinsic motivation. The following work, in a chronological order, is the study among 150 Pakistani employees done by Khan, Latif, Jalal, Anjum & Rizwan (2014), which relates diverse aspects of CSR and the employees’ global motivation. Its results are not unanimous: there are significant and positive relations along with others which are not significant, both positive and negative. Jie & Hasan (2016) note positive and significant relations between diverse dimensions of CSR (workplace, marketplace, environment and community) and intrinsic motivation for the case of 37 Malayan employees. It is also argued that CSR activities promote intrinsic (moral/ethical) motives in motivated employees in the banking sector in Evans, He, Boadi, Bosompem & Avornyo (2020). Lastly, there is Hur, Moon & Ko's (2018) study among 250 South Korean workers. The results are the existence of a positive and significant relation between the two variables considered: CSR and internal motivation.

For this reason, the first hypothesis of our model is formulated in the following terms.

HYPOTHESIS 1(H1): CSR is positively correlated with the employees’ internal motivation.

2.2CSR and employee trustCurrently, employee trust in relation to CSR activities have attracted the focus of researchers. Authors such as (Yadav, Dash, Chakraborty & Kumar, 2018), believe that when they feel that their organisations are serving the benefits of all stakeholders, employees' perception of CSR makes them worthy and increase their confidence. To maintain a relation of trust with its employees is fundamental for organisations. However, due to their changing nature and multidimensional structure in all the possible environments, it is complicated to identify which causes determine that an organisation is trustable for its employees. Trust begins in the top management of a firm and is transmitted downwards. If the management shares the good and bad news frequently and openly with its employees, they improve communication and generate trust between managers and employees (Nasomboon, 2014; Tzafrir, 2005);

Diverse authors (Geyskens, Steenkamp, Scheer & Kumar, 1996; Coulter & Coulter, 2002) have analysed the trust construct from two different approaches: as a component of behaviour and of the willingness to trust a colleague, and as an emotional component associated with a set of attributes, such as competence, honesty and benevolence. Meanwhile, Ganesan (1994) understands that trust reflects the assurance of one party that the other party is fair, believable and trustable. On the other hand, Casaló, Flavián & Guinalíu (2007) consider that trust is associated with qualities such as honesty, responsibility, benevolence and comprehension, while Morgan & Hunt (1994) state that trust is the conviction that the other party will act with a high level of integrity to achieve positive results, or at least will not work to unpredictably cause negative consequences. According to Schoorman, Mayer & Davis (2007), the notion of trust has distinct dimensions and can be used at various levels of analysis: interpersonal, intergroup and interorganisational.

We can define the term trust as the willingness "of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party" (Mayer et al., 1991) and the desire, under a situation of risk, to trust another person, institution, group, etc. In other words, trust is made up of two basic components: reliance/dependency and risk/vulnerability (Yue, Men & Ferguson, 2019).

As to the relation between CSR actions and employee commitment, the research consulted by the authors of this article indicate, generally speaking, a positive and significant relation. Nonetheless, the results do not absolutely coincide.

Farooq et al. (2014) obtain partly contradictory results in a study among 378 South Asian employees, although in their case they take into consideration 4 dimensions of CSR (towards the community, towards the environment, towards consumers and towards employees): all the relations are positive, but that between environmental CSR and trust is not significant. The work of Yu & Choi (2014) confirms the positive and significant relation between the two variables pointed out for a sample of 168 Chinese workers. A research among 210 employees of Hindu firms (Yadav & Singh, 2016) also achieves favourable and significant results in the relation between the perception of CSR and employee trust. The findings of Gaudencio et al.’s (2017) study shows that perceptions of CSR predict the attitudes and behaviours of the employees directly through the mediator role of trust in the organisation. Ghosh (2018), according to an analysis of online questionnaires completed by 536 Indian employees, indicates that the employees feel deeply identified with their organisation when they have a positive appreciation of the firm's CSR initiatives. This is through the development of organisational trust based on the attachment and favourable perception of the workers within the organisation. The work of Manimegalai & Baral (2018), with a sample of 284 Indian workers, positive relations are found in all the cases between the CSR dimensions, although not significant in every case. Finally, Su & Swanson (2019) with a sample of 441 employees from 8 hotels in China find a positive relationship between CSR activities and employee confidence. Therefore, the following hypothesis to be formulated is:

HYPOTHESIS 2 (H2): CSR activities have a direct and positive relation with employee trust.

2.3Internal motivation and commitmentSome research has addressed the relationship between motivation and commitment within the field of organisational psychology (Meyer, Becker & Vandenberghe, 2004). Other studies, such as those by (Moynihan & Pandey, 2007), although they affirm their relevance within the work environment and make a distinction between motivation and commitment, do not explore the causal relationships between the two concepts. While some papers do not consider both constructs as synonyms, they discuss them together in the context as "motivation and commitment", not establishing any significant difference between the two concepts (Bresnen & Marshall, 2000).

Among the articles that address the relationship between motivation and commitment, some researchers highlight the positive influence of motivation on organisational commitment and consider that the key to commitment is intrinsic motivation and the work itself (Gagné, Chemolli, Forest & Koestner, 2008; Chalofsky & Krishna, 2009 Bang, Ross & Reio Jr., 2013; Purnama, Sunuharyo & Prasetya, 2016).

Motivation is recognised as a body of effective forces in people (Pinder, 1998). It is considered as the reason behind every action, from the start, continuing an activity to the overall direction of a person's behaviour (Yasrebi, Wetherelt, Foster, Afzal, Ahangaran & Esfahanipour, 2014). Other authors consider it as one of the prerequisites for extending engagement (De Baerdemaeker & Bruggeman, 2015). Intrinsic motivation, therefore, is an irrefutable factor that determines employees' preventive efforts in their workplaces (Ganjali & Rezaee, 2016). In general, internal motivation is the tendency of employees to perform their job in a better way to achieve inner satisfaction, as a motivated employee is considered a key factor for the success of any company.

As a result, organisational commitment is also conceived as a powerful motivational source (Meyer et al., 2004). Organisational commitment is considered a nexus or connection of the individual with the organisation and can be defined as the level of involvement of subordinates with their organisation and its corporate values (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990). Committed workers are aware of their responsibility in the fulfilling of functional objectives, perform a role with high levels of excellence and positively influence their colleagues for the achievement of organisational goals (Harter, Schmidt & Hayes, 2002).

Kahn's (1990) work offers the first conceptualisation of commitment at work: "the members of the organisation's use of their work functions". For Maslach & Leiter (1997), the building of commitment is the opposite of burn out (someone who does not experience burn out at work must participate in their work). Robbins & Judge (2015) describe commitment as the condition in which an individual favours an organisation and aims to maintain membership in it. On the other hand, Macey, Schneider, Barbera & Young (2009) and Mone & London (2010) coincide in indicating that employee commitment is one of the determinants of high levels of individual performance. For Suresh (2012), commitment has to be understood as an association between employees and an organisation, reflected in employees’ decisions to stay in or leave their job, which can affect a person's attachment and identification with the organisation he or she serves (Karami, Farokhzadian & Foroughameri, 2017). An employee with high levels of commitment towards the organisation is able to add productivity and competitive advantage to a company (Saraih, Aris, Karim, Samah, Sa'aban & Abdul Mutalib (2017). Likewise, organisational commitment comprises the connection, a person's involvement with corporate values, employee identification with the organisation and maintaining a positive commitment to the company. This generates higher performance (Risla & Ithrees, 2018; Suharnomo & Fathyah, 2019).

Mathieu & Zajac (1990) indicate that various approaches exist about organisational commitment. Attitudinal commitment has been defined as the relative strength of the identification and involvement of individuals with a specific organisation (Vandenberg & Lance, 1992). On the other hand, calculated commitment can be defined as "a structural phenomenon which occurs as a result of individual-organisational transactions and alterations in side-bets or investments over time" (Hrebiniak & Alutto, 1972, p. 556). Other authors (Choong, Lau & Wong, 2011) have underscored the existence of 3 components of commitment: affective, normative and continuance. This work, however, uses the concept of organisational commitment in a broad sense, although it takes into account the works which have related internal motivation and employee commitment in any of their acceptations and components.

This section analyses the results found in the literature about the relation between the employees’ internal motivation and their commitment to their organisation. In the 20th. century we have located two investigations which have related internal motivation and commitment. The first is Mathieu & Zajac's (1990) meta-analysis concerning the antecedents, consequences and correlations of organisational commitment. These authors point out that the relation between intrinsic motivation and commitment is positive and significant. The meta-analytical work of Eby, Freeman, Rush & Lance (1999) positively and significantly relates intrinsic motivation with employees’ affective commitment.

In this century we have identified 13 articles: Karatepe & Tekinkus (2006), Gagné, Chemolli, Forest & Koestner (2008), García-Más et al. (2010), Choong et al. (2011), Galletta, Portoghese & Battistelli (2011), Hayati & Caniago (2012), Yousaf, Yang & Sanders (2015), Kumar, Mehra, Inder & Sharma (2016), Al-Madi, Assal, Shrafat & Zeglat. (2017), Kalhoro, Jhatial & Khokhar (2017), Kuvaas, Buch, Weibel, Dysvik & Nerstad (2017), Potipiroon & Ford (2017), and Gheitani, Imani, Seyyedamiri & Foroudi (2019). Almost all these studies, with the exception of three (Hayati y Caniago, 2012; Kumar et al., 2016; Kuvaas et al., 2017), find positive and significant relations between the variables considered. In the case of the research of Hayati & Caniago (2012), the relation is negative and not significant; in the study of Kumar et al. (2016) it is positive and not significant. While in the work of Kuvaas et al. (2017), where motivation and the three types of commitment are related, significant positive and negative relationships are found.

Having presented the criteria concerning the previously mentioned constructs, the third hypothesis formulated is:

HYPOTHESIS 3 (H3): Internal motivation is positively related with employee commitment.

2.4Employee trust and commitmentSome authors argue that trust and people's commitment to the organisation is the most relevant component that top management should consider as an appropriate human resource practice (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2005; Thompson & Heron, 2005). Other research considers that trust increases organisational commitment and studies supporting this relationship are not new (Aryee et al., 2002; Mukherjee & Battacharya, 2013). Likewise, according to (Klimchak, Ward & MacKenzie, 2020), employees with greater trust in their organisations are more likely than others to be affectively committed to their organisations.

It is important to address certain important definitions of both constructs, starting with the argument that defines trust as the credibility that one party will perform an action according to the expectations of the other party under vulnerable conditions (Sanzo et al. 2003), 2003). For leaders the generation of trust is indispensable, as it strengthens the commitment and loyalty of their employees (Anantatmula, 2010). Other authors determine that trust gives rise to a relationship of social exchange of reciprocity between the employee and the organisation, in which the worker feels affection and good intentions towards the company, generating greater identification with the company and the desire to continue being part of it. (Xiong, Lin, Li & Wang, 2016). The emergence of trust is based on "some kind of behavioural manifestation" from their interactions with their supervisors or leaders (Dietz, 2011, p. 215). While Bük, Atakan-Duman & Paşamehmeto¿lu (2017) found that subordinate trust is based on the leader's leadership and behaviour, other authors concluded that when employees feel trust, they work hard, always concur and go above and beyond the call of duty and perceive themselves satisfied with their work (Setyaningrum, Setiawan, Surachman & Dodi, 2020). Employee trust therefore enhances harmonious relations between managers and employees, contributing to the joint achievement of organisational goals.

Regarding organisational commitment, some previous researchers found that this construct was a one-sided concept; however, Meyer & Allen (1991) introduced the multidimensional nature of the variable organisational commitment (Masud & Daud, 2019). Commitment is also considered as the dependence and belongingness of an employee on and regarding the organisation (Zarei, Sayyed & Akhavan, 2012). In another research work, organisational commitment is defined as an employee's loyalty to the organisation's goals and recognition and acceptance of its corporate values (Yeh, 2014). Other authors state that organisational commitment is the force that identifies and engages an employee in an organisation (Top, Akdere & Tarcan, 2015). A recent study found that organisational commitment is the involvement, identification and loyalty of an employee with and towards a particular company, represented by the feelings, emotions and obligations of the individual concerning the companies he or she serves (Rehman, Hafeez, Aslam, Maitlo & Syed, 2020).

The authors of this paper have identified 8 research works analysing the relationship between employee trust and organisational commitment. All of them have been published from 2000 onwards.

Perry (2004) finds that the relation between employee trust in supervision and affective commitment is inverse, though not significant. On the other hand, Yilmaz (2008), in a sample of 120 Turkish teachers, indicates that there is a positive and significant relation between trust and global commitment.

Cho & Park's (2011) work, with almost 20,000 North American workers, notes positive and significant relations between 3 aspects of trust (towards management, towards supervision and towards colleagues) and the employees’ global commitment. In an investigation in Turkey (315 teachers), Celep & Yilmazturk (2012) show a significant and positive relation between the two variables considered.

Also in Turkey, Top, Tarcan, Tekingündüz & Hikmet (2013) analyse the relation between employee trust and commitment, and reach the same conclusion: a direct and significant correlation. In the work of Farooq et al. (2014) already commented on, the relation between organisational trust and affective commitment is analysed and the results indicate that it is significantly positive.

Fard & Karimi's (2015) study among 180 Iranian employees also offers favourable results (positive and significant) in the relation between trust and the employees’ global commitment. Vanhala, Heilmann & Salminen (2016) in their work with 3 different Finnish samples present contradictory findings on the relationships between trust and commitment. On the one hand, in relation to trust towards co-workers there are non-significant positive and negative relationships. On the other hand, in relation to trust towards managers there are positive but non-significant relationships. Finally, trust towards the organisation is positive and significant.

Two studies appeared in 2017. The results of Gaudencio et al.'s (2017) and Jiang, Gollan & Brooks (2017) investigations lead to what has already been pointed out in the previous paragraphs: a positive and significant relation between trust and affective commitment.

The meta-analysis of the relationship between the two variables by Akar (2018) points to the existence of a positive and significant relationship, albeit of moderate relevance. On the other hand, a positive and significant relationship is also identified in the following studies: Aybar & Marşap (2018), Gholami, Saki Hossein Pour (2019), Liggans, Attoh, Gong, Chase, Russell & Clark (2019), Akgerman & Sönmez (2020), Nguyen, Pham, Le & Bui (2020), Gill, Ansari & Tufail (2021), and Landrum III (2021).

Due to what has been described, the fourth hypothesis formulated is:

HYPOTHESIS 4 (H4): Employee trust is positively related with commitment towards the firm.

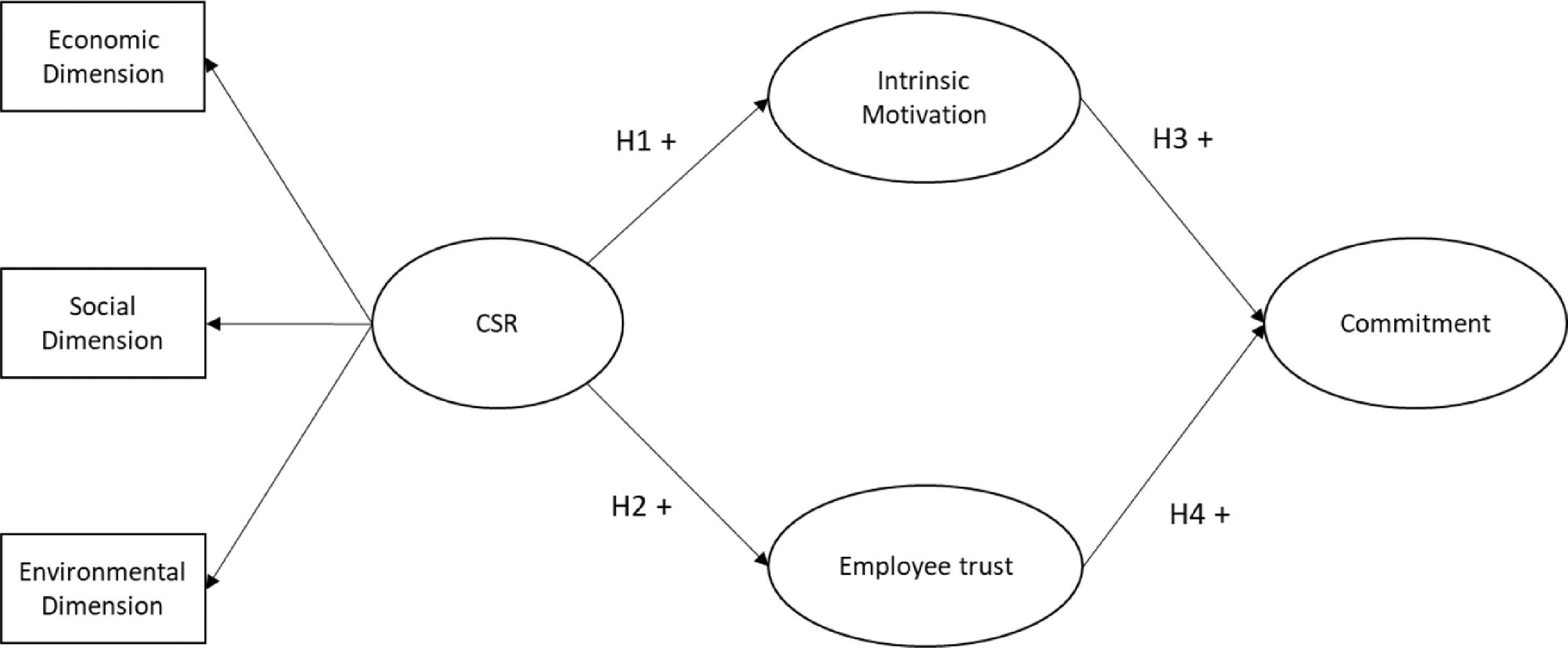

The relations gathered in the four hypotheses proposed are presented graphically in Figure 1, which shows the causal model proposed.

3METHOD3.1ParticipantsTo achieve the goals of this research an empirical study was done centred on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) of massive consumption distributors in Manabí. This was due to their growing importance for the socio-economic development of the province, being represented in this investigation by those SMEs dedicated to the distribution of foods, toiletries, cleaning products, drinks, milk products, among other massive consumption products in the city of Portoviejo (capital of Manabí - Ecuador). The city's last Economic Census, carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC), determined that almost 95% of its firms belonged to this INEC business typology (2010).

This segment of firms is included within the 54% of firms at the national level which belong to the INEC wholesale and retail trade sector (2010). This means that a little over half of the firms in Ecuador deal in trade, as is highlighted by the Directorate of Firms and Establishments (2014). Manabí concentrates 37% of the firms in this commercial field, mainly in the trade sector, as is shown by the Observatory of SMEs of the Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar (2014). They are drivers of sustainable development for this province of Ecuador.

For the data collection, the questionnaires were distributed among the employees (managers and workers) of different firms of the sector. A total of 510 surveys were distributed to the target enterprises. For various reasons only a total of 318 valid questionnaires were received.

The data of Table 1 show that 79.6% of the respondents are men and only 14.8 are women; 5.7% do not indicate their sex. The majority of the respondents have “position 4” jobs, followed by members of group 3. As to age, the majority are spread over the groups corresponding to positions 2 and 3. The respondents are mainly married (40.6%), with an educational level “2” (56.3%), have been in the firm less than 3 years (67.9%) and have a salary below 800 US $ (81.8%).

Respondent characteristics

| Absolute frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Sex | ||

| Male | 253 | 79.6 |

| Female | 47 | 14.8 |

| Lost | 18 | 5.7 |

| (b) Job | ||

| Manager | 4 | 1.3 |

| Middle Level Manager | 24 | 7.5 |

| Operational staff | 90 | 28.3 |

| Sales staff | 151 | 47.5 |

| Service assistant | 20 | 6.3 |

| Lost | 29 | 9.1 |

| (c) Age | ||

| 65 years old and more | 40 | 12.6 |

| Between 50 – 64 years old | 83 | 26.1 |

| Between 40 – 49 years old | 125 | 39.3 |

| Between 30 – 39 years old | 49 | 15.4 |

| Between 24 - 29 years old | 11 | 3.5 |

| Between 18 - 23 years old | 1 | .3 |

| Lost | 9 | 2.8 |

| (d) Marital status | ||

| Married | 129 | 40.6 |

| Single | 95 | 29.9 |

| Divorced | 40 | 12.6 |

| Common-law relationship | 46 | 14.5 |

| Widow(er) | 3 | .9 |

| Lost | 5 | 1.6 |

| (e) Educational level | ||

| Basic education (10 years old) | 13 | 4.1 |

| Secondary school (13 years old) | 179 | 56.3 |

| Higher studies (degree level: 6 years) | 120 | 37.7 |

| Postgraduate higher studies level (speciality: Master's: up to 2 years) | 2 | .6 |

| Lost | 4 | 1.3 |

| (f) Labour seniority | ||

| Less than 1 year | 116 | 36.5 |

| 1 to 3 years | 100 | 31.4 |

| 2 to 5 years | 38 | 11.9 |

| More than 5 years | 52 | 16.4 |

| Lost | 12 | 3.8 |

| (g) Salary | ||

| Less than 400 $ USD | 101 | 31.8 |

| 400-800 $ USD | 159 | 50.0 |

| 800-1200 $ USD | 43 | 13.5 |

| 1200-1600 $ USD | 7 | 2.2 |

| 1600 $ USD and over | 8 | 2.5 |

All the scales used to measure the model's variables, both dependent and independent, have been 5-option Likert-type, where 1 means “totally disagree” and 5 “totally agree”.

In the field of Spanish-language research on corporate social responsibility (CSR), we have identified three proposals (Agudo-Valiente, Garcés-Ayerbe & Salvador-Figueras, 2012; Pérez, Martínez & Rodríguez del Bosque, 2012; Gallardo, Sánchez & Castilla, 2015) with appropriate levels of reliability and validity, which have allowed us to select most of the 53 items in the questionnaire. Despite this, we have had to add some items from other works. In the economic dimension, we have incorporated proposals from Turker (2009) and Lu, Lee & Cheng (2012). In the social and environmental dimensions, we have added components obtained from the works of Montiel (2008), Martínez-Carrasco, López & Marín (2013) and Palacios, Castellanos & Rosa (2016). The original scale consists of 53 items: 18 in the economic dimension, 23 in the social dimension and 12 in the environmental dimension.

The scale on intrinsic motivation consists of seven questions. The first five are an adaptation to Spanish of the items included in the instrument designed by Skudiene & Auruskeviciene (2012). The sixth ("I believe that working in this company helps me to improve my life") comes from the work of Judge & Watanabe (1993) and Barakat et al. (2016). The last one ("I feel happy when I am working intensively") has been obtained from the contributions of Schaufeli, Bakker & Salanova (2006), Ferreira & Real de Oliveira (2014) and, finally, Polo-Vargas, Fernández-Ríos, Bargsted, Ferguson & Rojas-Santiago (2017).

Eleven items have been used in our survey to measure organisational commitment, decomposed into the 3 dimensions proposed by Allen & Meyer (1990). The first 6 items have been adapted from the proposals of Juaneda & González (2007) and Martínez-Carrasco, López & Marín (2013). The aspects relating to pride and sense of belonging to the company are adapted from the contributions of Mowday et al. (1979) and Dutton & Dukerich (1991). The last four components of this scale have been adapted and transferred from the items included in the following scientific articles: Meyer & Allen (1991), Hartline & Ferrell (1996), Schaufeli et al. (2006), Ferreira & Real de Oliveira (2014), Ruizalba, Vallespín & González (2014) and Polo-Vargas et al. (2017).

In relation to the scale of employee trust towards the organisation, 3 propositions have been included, adapted and transferred to Spanish from the instrument designed by Togna (2014).

3.3Data analysisWe have analysed the research model with the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique. This is an analysis technique of variance-based structural equations models. There are various reasons for choosing this technique: (1) the use of first- and second-order constructs, which means that the model is quite complex; and (2) the need to calculate the scores of the second- order latent variables (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012; Roldán, Sánchez-Franco & Real, 2017). The measurement model used in this work is composite and reflective (Mode A). This makes the use of traditional PLS viable (Sarstedt, Hair, Ringle, Thiele, & Gudergan, 2016). We have employed the PLS SmartPLS 3.2.4 software (Ringle, Wende & Becker, 2015).

The use of a single questionnaire with a self-reporting format to obtain the data of the latent variables made it necessary to check the existence or not of common variance between them. In line with Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee & Podsakoff (2003) and Huber & Power (1985), we have followed the procedural steps relative to the design of questionnaires. We separate the different measurements and we guarantee the anonymity of the respondents. The presence of common influence in the answers was measured with Harman's (1967) test. The 74 elements of the questionnaire considered have been grouped into a total of 10 factors, and the largest of them explains 48% of the variance. We can, therefore, in accordance with Podsakoff & Organ (1986), indicate the absence of a common factor of influence among these items.

The perspective of the latent model (MacKenzie, Podsakoff & Jarvis, 2005; Real, Leal & Roldán, 2006) was used when analysing the relations between the distinct constructs of the model and its indicators. In the case of the second-order constructs, it was opted for the two-step approach (Calvo-Mora, Leal & Roldán, 2005). This consists of obtaining the scores of the latent variables via the use of the PLS algorithm to optimally combine and ponder each dimension's indicators. In this way, the first-order dimensions (factors) become the indicators of the second-order factors.

4RESULTSAs in any structural equation analysis we have proceeded to evaluate both the measurement model and the structural model.

4.1Measurement modelTable 2 gathers the data necessary to begin with the validation of the measurement model: to determine the reliability of the individual items. We have measured all the latent variables (constructs) in mode A (reflective). It is observed that the factorial loadings of all the items, as well as the CSR dimensions, obtain values above the minimum criterion of 0.707 (Carmines & Zeller, 1979). Of the 74 items of the original questionnaire 8 have been eliminated in the economic dimension of CSR and 2 others in the social dimension.

Individual reliability, composite reliability and average variance extracted for the first-order factors and second-order factors and dimensions

| Construct/dimensionand indicator | Loading | Cronbach alpha | Compositereliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (CSR) | 0.813 | 0.888 | 0.726 | |

| ECONOMIC DIMENSION | 0.835 | 0.914 | 0.928 | 0.565 |

| The products and/or services comply with national and international standards. | 0.743 | |||

| The guarantee of the products and/or services is higher than the market average. | 0.726 | |||

| The customers’ interests are incorporated into the business decisions. | 0.734 | |||

| The respect for the consumers’ rights is a priority of the management. | 0.822 | |||

| The firm is recognised in the market because one can trust its actions. | 0.757 | |||

| The firm makes an effort to enhance stable relations of collaboration and mutual benefit with its suppliers. | 0.804 | |||

| The firm is aware of the importance of incorporating responsible purchases (that is to say, they prefer and select responsible suppliers). | 0.726 | |||

| Attention is paid to how the suppliers manage ethical performance with their commercial partners. | 0.724 | |||

| There exists a fair system of exchange with suppliers and customers.. | 0.723 | |||

| The firm's economic management is worthy of public, regional and national support. | 0.748 | |||

| SOCIAL DIMENSION | 0.868 | 0.966 | 0.969 | 0.597 |

| The firm is concerned about improving its employees’ quality of life. | 0.761 | |||

| There is a clear commitment with the creation of employment (acceptation of interns and trainees, creation of new jobs). | 0.786 | |||

| The return on capital (the shareholders’ profits) and the employees’ salaries are above the sector's average. | 0.790 | |||

| There exist policies of labour flexibility which enable reconciling work life with personal life. | 0.719 | |||

| The employees’ remuneration (salaries) is related with their competences and yields. | 0.796 | |||

| The firm carries out salary reviews based on the degree of professional development | 0.754 | |||

| The firm takes care of its employees’ personal and professional life. | 0.817 | |||

| The firm invests in order for the work to be a place of personal and professional development, having improved the staff's satisfaction. | 0.816 | |||

| There are levels of labour health and safety beyond the legal minimums. | 0.721 | |||

| The employees’ professional development and continuous training is fostered in the firm. | 0.831 | |||

| The employees’ proposals are considered in the firm's executive management decisions. | 0.804 | |||

| The firm's aim is to give its employees labour stability. | 0.745 | |||

| There exists equality of opportunities for all the employees, avoiding discriminations based on sex, age, friendly or family relationships, or other motives. | 0.745 | |||

| The firm supports education and cultural activities in the communities where it operates. | 0.792 | |||

| The firm applies equality criteria in topics of remuneration and the development of professional careers and, in this sense, there are not favourable treatments for staff who are next of kin or relatives. | 0.800 | |||

| The firm helps to improve the quality of life in the communities where it operates. | 0.765 | |||

| The firm's decisions incorporate the interests of the communities where it operates. | 0.781 | |||

| Social and economic development is stimulated, fostering the wellbeing of society. | 0.812 | |||

| The firm takes part in social projects aimed at the community. | 0.739 | |||

| The employees are encouraged to participate in volunteer activities (community service) or in collaboration with NGOs. | 0.717 | |||

| The mechanisms of dialogue with the employees are dynamic. | 0.718 | |||

| ENVIRONMENTAL DIMENSION | 0.853 | 0.949 | 0.956 | 0.643 |

| The use of natural resources is reduced to the minimum. | 0.757 | |||

| Raw materials, work in progress and/or transformed with the minimum environmental impact are used. | 0.758 | |||

| Investments are planned to reduce their environmental impact. | 0.831 | |||

| Recyclable containers and packaging are used. | 0.810 | |||

| Energy saving is considered to achieve greater efficiency levels. | 0.822 | |||

| Introducing alternative energy sources is positively valued. | 0.806 | |||

| Materials and waste are recycled. | 0.774 | |||

| Ecological services and products are designed. | 0.813 | |||

| The firm takes part in activities related with the protection and improvement of the environment. | 0.816 | |||

| Measures are taken to reduce the emissions of gases and waste. | 0.823 | |||

| The firm is concerned about environmental training. | 0.842 | |||

| Responsible consumption is fostered (information about the efficient use of products, waste, among others). | 0.763 | |||

| INNER MOTIVATION (INMOT) | 0.917 | 0.934 | 0.668 | |

| I want my work to offer me opportunities to develop my career | 0.725 | |||

| I feel more comfortable when I'm involved in the decision-making process. | 0.818 | |||

| I don't mind what the result of a project is, I'm satisfied if my firm provides truthful information to society | 0.826 | |||

| In a good psychological atmosphere, I like doing my work | 0.843 | |||

| The more difficult the problem is, the more I enjoy trying to solve it | 0.832 | |||

| I believe working in this firm helps me to improve my life. | 0.851 | |||

| I feel happy when I'm working intensely. | 0.819 | |||

| EMPLOYEE TRUST (ETRUST) | 0.877 | 0.924 | 0.802 | |

| I trust the company. | 0.873 | |||

| The company takes the employees’ opinions into consideration. | 0.904 | |||

| I trust the decisions that the management makes. | 0.910 | |||

| COMMITMENT (COMM) | 0.963 | 0.968 | 0.736 | |

| Normally I do more than what is expected to help the organisation to achieve its aims. | 0.707 | |||

| I would accept almost any post to continue collaborating with this organisation. | 0.770 | |||

| I find that my values and the values of the organisation are very similar. | 0.853 | |||

| I'm proud to say I'm part of this organisation. | 0.900 | |||

| This organisation really inspires the best of me when developing my activity. | 0.891 | |||

| I'm very happy to have chosen this organisation to work in and not another. | 0.905 | |||

| For me this is the best of all the possible organisations in which to work. | 0.905 | |||

| I would feel a bit guilty if I had to leave the firm now. | 0.850 | |||

| When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. | 0.874 | |||

| My job inspires me. | 0.901 | |||

| In my job I feel full of energy. | 0.855 |

To measure the reliability of the constructs, the composite reliability indices have been calculated (ρc) (Werts, Linn & Jöreskog, 1974). In all the cases, we observe a compliance with the minimum requirement: a composite reliability above 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978). As to the convergent validity, all the latent variables surpass the minimum level of 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) in the AVE as Table 2 illustrates.

The analysis of the discriminant validity of the diverse constructs (latent variables) has been done based on two criteria: that of Fornell-Larcker and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The data are gathered in Tables 3 and 4. The Fornell-Larcker criterion is strictly met in all the cases. As to the HTMT ratio, the data fulfil the less strict criterion, as all the values are under 0.9. Taking the data together, we consider that there is discriminant validity between the constructs.

Averages, typical deviations and construct correlations

| Constructs | Mean | s. d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59.27 | 954.050 | 0.852 | |||

| 36.31 | 912.931 | 0.610 | 0.817 | ||

| 37.67 | 942.959 | 0.659 | 0.603 | 0.896 | |

| -3.10 | 906.003 | 0.680 | 0.815 | 0.745 | 0.858 |

Diagonal elements (bold figures) are the square root of the variance shared between the constructs and their measures. Off-diagonal elements are the correlations between constructs. For discriminant validity, the diagonal elements should be larger than off-diagonal ones.

After the valuation of the measurement model and having fulfilled all the requirements, we can value the structural model.

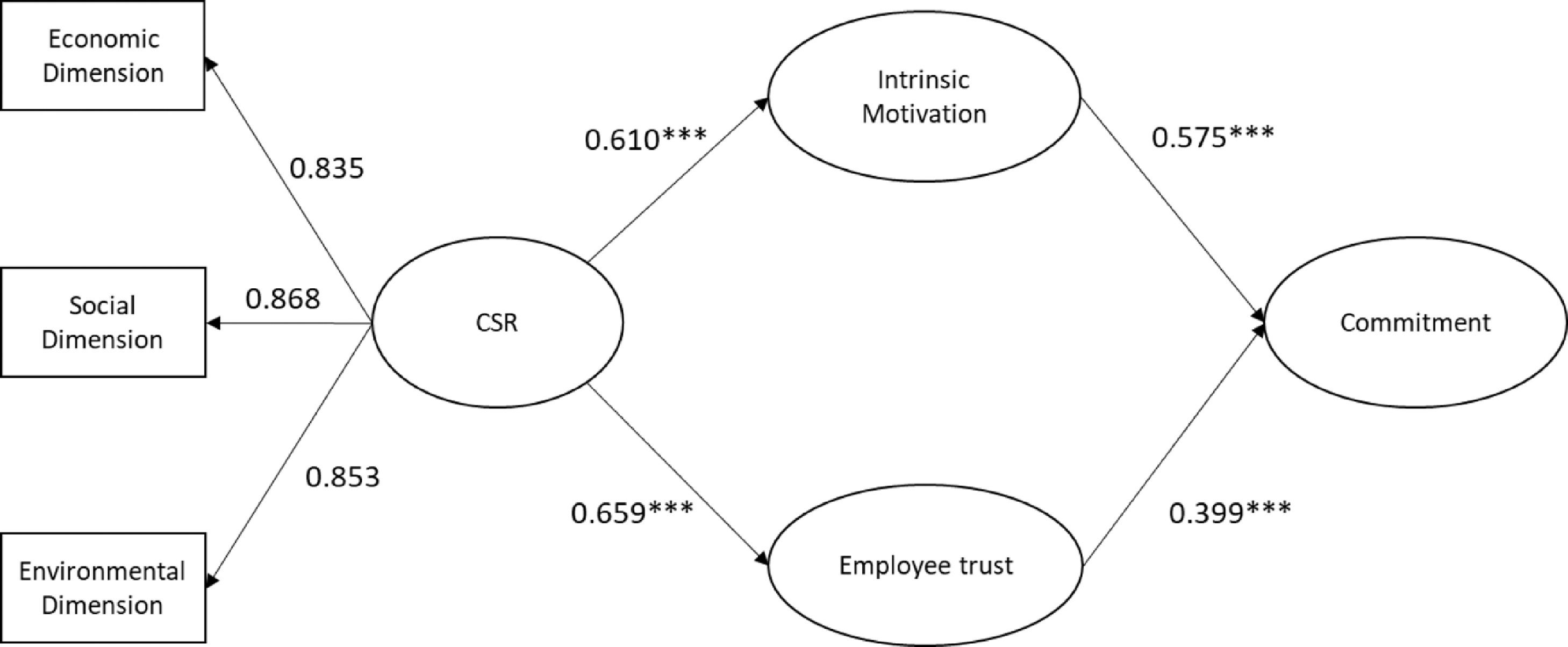

4.2Structural modelIn the case of the structural model, we have analysed: the sign, size and significance of the path coefficients, the R2 values and the Q2 test. In accordance with Hair Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt (2017), we have used the bootstrapping technique with 5,000 replications to determine the t statistics and the confidence intervals and with this the significance of the relations (see Figure 2). Table 5 offers the direct effects (path coefficients), the value of the t statistics and the corresponding confidence intervals, along with the R2 and Q2 values. All the direct effects are significant and positive and, consequently, all the hypotheses of the model proposed are supported by the data. The R2 values show an appropriate predictive level for all their variables: trust, internal motivation and commitment. The Q2 values also spotlight the predictive relevance of the model as all are above 0.

Direct effects on endogenous variables

| Effects onendogenous variables | Direct effects | t Value (bootstrap) | Percentile 95% confidence interval | Correlations | Explained variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner motivation(R2 = 0.372 / Q2 = 0.229) | |||||

| H1: CSR | 0.610⁎⁎⁎ | 10.934 | [0.514; 0.697] Sig | 0.610 | 37.21% |

| Employee trust(R2 = 0.434 / Q2 = 0.327) | |||||

| H2: CSR | 0.659⁎⁎⁎ | 17.120 | [0.593; 0.719] Sig | 0.659 | 43.43% |

| Commitment(R2 = 0.766 / Q2 = 0.520) | |||||

| 0.575⁎⁎⁎ | 11.302 | [0.488; 0.654] Sig | 0.815 | 46.86% |

| 0.399⁎⁎⁎ | 7.974 | [0.317; 0.482] Sig | 0.745 | 29.73% |

Table 6 shows the values of the indirect effects of the CSR variable on the endogenous variable commitment. The results indicate that the total effect is significant and positive and that all the indirect paths significantly contribute to it. That is to say, that the firm's CSR actions produce effects on employee commitment, both through the internal motivation of the employees and the confidence generated. Notwithstanding, the effect through internal motivation seems slightly greater than through trust.

5DISCUSSION/CONCLUSIONSThis article about the relation between CSR activities, intrinsic motivation, employee trust and commitment with the organisation offers a new perspective concerning the effects of firms’ CSR practices. The authors have not found any similar article on these relations. The current investigations have only dealt with one of the branches of the relation: on the one hand, CSR, motivation and commitment (Khan et al., 2014), and, on the other hand, CSR, employee trust and commitment (Farooq et al., 2014; Gaudencio et al., 2017).

The results of this research are similar to those attained by Kahn et al. (2014) as to the relation between CSR, motivation and commitment, with the exception that the authors indicated do not analyse the mediation and only take into account the direct relations. Their results show that there are positive and significant relationships between external CSR (local communities and business partners) and employee motivation, and there is also a significant and positive relationship between employee motivation and organisational commitment, although their research found an insignificant relationship between internal CSR, external CSR (customers) and employee motivation. In the other branch of our model, our findings coincide with those of the works indicated (Farooq et al., 2014; Gaudencio et al., 2017), both in the direct relations between variables and the indirect or mediated relations: employee trust is a variable which mediates the relation between CSR and commitment to the firm.

Yet, this investigation offers new findings about the relation between the variables considered: the mediator effect between CSR and commitment is greater in the case of internal motivation. So, although both mediator variables (trust and intrinsic motivation) connect CSR practices and employee commitment, firms must bear in mind that actions on intrinsic motivation cause the most relevant changes.

This investigation also has some limitations. First, the scant generalisation of its results to the Ecuadorian reality given that the firms are located in a single zone of the country and belong to a specific activity. Second, the consideration of other variables which could condition the relations studies: sex, age, etc. Finally, new determinant factors of the relations between the endogenous and exogenous variables could be included.