Drawing upon a genealogy density of chairpersons’ native places for Chinese family firms to measure the intensity of clan culture, this study uses regression analysis and chooses the fixed model with firm clusters to examine the impact of regional clan culture on firms’ corporate social responsibility (CSR). The findings suggest that family firms’ CSR performance increases with greater clan cultural intensity; specifically, firms characterized by a robust clan culture tend to engage more in socially responsible activities, prioritizing internal CSR over external initiatives. Drawing on imprinting theory, the results illustrate that clan culture shapes CSR activities by influencing chairpersons’ ethics and fostering a sense of mutual assistance. Further insights indicate that the influence of clan culture is particularly pronounced when entrepreneurs operate within their local environments or hail from large clans. However, factors such as population mobility, formal institution development, and the gender of the chairperson serve to weaken the impact of clan culture. In general, this study contributes evidence toward understanding the drivers behind family firms’ CSR behaviors from the vantage point of traditional culture.

Family firms, ubiquitous worldwide, wield substantial influence in various economies (Rehman et al., 2023). In China, for instance, according to data from the State Administration of Market Supervision and Administration, private enterprises surged from 10.857 million in 2012 to 47.011 million in 2022, contributing over 60% of the nation's GDP and tax revenue, with the majority being family-owned1. Unlike state-owned enterprises driven by mandatory social responsibility aligned with political agendas, family firms enjoy more autonomy in their CSR initiatives. An intriguing finding suggests that owners of family firms exhibit a heightened commitment to CSR compared to their non-family counterparts (Battisti et al., 2023). So what are the key factors that drive family businesses to be socially responsible? The operation of enterprises cannot be separated from specific cultural environments, especially in an emerging market country such as China, where the legal system is imperfect, and informal institutions such as culture wield significant economic influence (Zhang & Ma, 2017). Clan culture, serving as the bedrock of family business governance, connects individuals and firms through strong informal contracts (Hsu, 1963). Amid China's imperfect contractual landscape, the bloodline affinity emphasized by clan culture provides a natural foundation of trust for relatives to enter the family business and participate in governance (Stock et al., 2024); and moral ethos, ethics, and principles of solidarity and reciprocity advocated by clan culture permeate family business governance, facilitating stakeholder relations and resource allocation. Thus, a compelling question arises: does clan culture emerge as the primary driver of CSR decisions in Chinese family firms?

Clan culture, a traditional aspect prevalent in Asian nations, extends beyond China to countries like Singapore, Korea, India, and Thailand (Liu et al., 2023). Clan culture is a kind of culture of tribe and family. For example, Korea has a strong family-centered culture of sharing the surname (Mo et al., 2023). A clan is a particular type of ethnic organization and there are many kinds of ethnic groups in Asia, such as the caste in India, chaebol in South Korea, and the clan in China (e.g., Enke, 2019; Munshi, 2019). Imprinting theory posits that individuals will create imprinting effects during sensitive periods which then impact their lives in the long term (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013). Childhood and adolescence, in particular, serve as crucial periods for the formation of values (Marquis & Qiao, 2020), where exposure to clan culture may subtly influence mindset formation and subsequent decision-making. Given their pivotal role in corporate governance, the cultural imprinting of chief executive officers (CEOs) profoundly impacts corporate strategy development (Ning et al., 2024). Recent literature has been examining how clan culture affects various aspects of firm performance such as stock recommendations, corporate natural resource disclosure, internationalization, entrepreneurship, and ownership concentration in family firms (Cheng et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022; Bhagavatula et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2023). However, the impact of clan culture on family enterprises’ CSR has not been thoroughly investigated so far.

China provides an optimal context for investigating this issue due to several key factors. First, the nation is well known for its long history of clan influences. Second, China's extensive data resources allow for the utilization of unique, meticulously gathered Chinese genealogy data, enabling the construction of a prefecture-level measure of local clan culture intensity, which can then be merged with firm-level data. Last, in contrast to developed nations, the CSR practices of family firms in emerging countries are often shaped more by informal institutional norms rather than formal institutional structures (Mariani et al., 2023). China, as a typical emerging country with rapid development and core values of Chinese clan culture, signals that clan culture could be a crucial informal institutional driver for advancing CSR. Accordingly, this study selects a sample of Chinese-listed family companies spanning the years 2006 to 2020 across various sectors, excluding financial services, and employs regression analysis to assess the impact of clan culture on the CSR activities of family firms.

This paper contributes to the relevant literature in the following ways. First, it provides a regional cultural perspective on the motivations driving CSR strategies. While prior research on the cultural drivers of CSR has mainly focused on national-level factors such as religious culture (Du et al., 2014) and Confucian culture (Wang & Juslin, 2009; Chen et al., 2021), or delved into organizational-level influences (Upadhaya et al., 2018; Kucharska & Kowalczyk, 2019), it has often overlooked the importance of clan culture at the regional level. Clan culture is a “family culture” rooted in common ancestry and has distinct regional characteristics due to its uneven presence across the country (Peng, 2004). This substantial variation in the strength of clans across Chinese regions provides a valuable opportunity to examine the role of culture in CSR within a single country. This paper adds to recent studies investigating the cultural factors driving Chinese family firms to engage in CSR and provides a fresh perspective on the influence of regional cultural characteristics.

Second, this paper proves that culture serves as an informal system collaborating with the formal system to foster CSR behaviors. By focusing on China's distinct social scene, this paper investigates the internal mechanism and boundaries of clan culture's impact on CSR. Given that China's formal economic and political system is still immature and evolving, it provides an opportunity for informal systems like culture to influence corporate behavior and societal outcomes. Our study aligns with existing findings that clan culture supplements the formal system by cultivating social trust among its members, thereby significantly impacting economic activities (Tang & Zhao, 2023; Chen & Zeng, 2024). This echoes a new research paradigm (Wang & Juslin, 2009), which claims that CSR is influenced by informal institutions such as culture. Consequently, managers can leverage the core values of clan culture in decision-making to enhance CSR performance within their organizations (Lorincová et al., 2022). We confirm that clan culture operates alongside legal and political frameworks as a social norm that reinforces CSR, not only within China but also in analogous contexts across Asia.

Finally, this paper also expands research on the upper echelons theory and imprinting theory. Previous studies grounded in these theories have explored how past experiences shape individual values and preferences (Graham et al., 2013; Benmelech & Frydman, 2015; Xu & Ma, 2022), often overlooking the exogenous attributes of the early-life cultural milieu that an individual cannot actively choose, such as clan culture. This is a critical limitation since one's cultural background has a direct and long-lasting imprint on their values and preferences (Xu & Ma, 2022). In the Chinese context, clan culture represents a fundamental aspect of the cultural heritage of family business managers and can significantly impact their CSR decision-making. This study extends the understanding of upper echelons and imprinting theories by demonstrating the role of chairpersons’ early-life cultural backgrounds in strategic decision-making. It is essential to note that exposure to clan culture during childhood is primarily exogenous, as children typically do not choose their living environment. This cultural immersion during formative years can directly and subtly shape the values of managers, thereby further influencing the CSR decisions made by family firms.

2Literature review and hypothesis development2.1The drivers of CSRThe growing importance of CSR in recent decades has prompted a dramatic increase in research on its drivers (Schwoy et al., 2023). From the perspective of external factors, although Zhang et al. (2023) discovered that economics has replaced politics as the main driver of CSR in China, the political factors, social norms, and public monitoring still have a non-negligible impact on CSR practices (Ng et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2023). Regarding internal factors corporates’ institution and executive characteristics such as positive emotions, all contribute to CSR behaviors (Wang et al., 2023a). According to the imprinting theory, the imprints of ideology and early famine experience to executives have a lasting impact on CSR decisions (Han et al., 2022; Liu & Luo, 2022; Xu & Ma, 2022).

Cultural role in the economy is increasingly being focused on by scholars, leading to a separate branch of research on the impact of culture on CSR. Culture implicitly leaves an imprint on individuals’ values which has a profound effect on their subsequent behavior (Guiso et al., 2006). Although several scholars have focused on the impact of culture on CSR, finding that national cultural variables (e.g. Confucianism), religious traditions, and responsible social norms have a significant effect on CSR activities (Du et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2023; You, 2024), they ignore the imprinting effect of the clan culture. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the relationship between clan culture and CSR using imprinting theory.

2.2Clan culture in ChinaA clan, known as “ZongZu” in Chinese, embodies a kinship-based hierarchical structure (Greif & Tabellini, 2010) led by patrilineal households tracing their lineage to a common male ancestor (Greif & Tabellini, 2017). Clan culture, an expression of a clan, is a type of traditional culture with distinctive Asian cultural values, emphasizing genealogy recording, lineage perpetuation, and ncestral homage in ancestral halls as the material carriers of its inheritance.

The practice of publishing genealogy books and forming kinship networks in China dates back to the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 B.C.E.). Following the Song Dynasty (960–1279 C.E), clan culture evolved into a “modern” form characterized by familial cohabitation. Clan culture has existed as a formal system for a long time, reaching its peak during the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1912 C.E.). The clan network, bound by blood relationships, has evolved into the fundamental unit within China's social relationship networks (Fei, 1998). However, the emphasis on pure-blood lineage as the cornerstone of clan cohesion began to wane during the Republic of China (1912–1949 C.E.) with the rise of the commodity economy. Upon the Chinese Communist Party's ascension to power in 1949, particularly during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976 C.E.), clan culture was labeled as a type of “feudal culture” and was abolished mainly in mainland China. However, clan-related cultural practices such as compiling genealogies and constructing ancestral halls resurged following China's economic reform in 1978. Despite over three decades of state suppression, China's clan culture endured (Zhang, 2020), with its norms, beliefs, and values continuing to influence contemporary Chinese society.

In fact, clan culture is the integration, derivation, and expansion of various root cultures—such as Confucian, Taoist, or Legalist cultures—within the clan. Central to clan culture are values such as clannish solidarity, reciprocity, collective reputation and interest, long-term values, limited trust, moral obligation, and social enforcement (Greif & Tabellini, 2017; Zhang, 2020; Liu et al., 2023). Overall, it can be regarded as a unique collectivist culture originating from the blood relationship but with an evident autocratic system and social hierarchy.

2.3Clan culture and CSRThe imprinting theory elucidates the enduring influence of an individual's early-life environment on their values and preferences. Imprinting is ‘‘a process whereby, during a brief period of susceptibility, a focal entity develops characteristics that reflect prominent features of the environment, and these characteristics continue to persist despite significant environmental changes in subsequent periods’’ (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013). Culture, encompassing the shared values and norms of a social group, exerts a more direct and enduring impact on individual values and behavior patterns than personality or experience (Guiso et al., 2006). Clan culture, functioning as a subculture, frequently shapes individuals during childhood (Greif & Tabellini, 2017). Following the logic of the imprinting theory, clan culture clan culture can imprint a long-term orientation onto the values of its members, forming cognitive imprints likely for those raised within a clan environment.

First, morality emerges as the external product of personal values that determines the degree of development of a harmonious society (Tan et al., 2018). In contrast to the rule-centric cooperation model prevalent in European contexts, Chinese clans have long prioritized moral principles (Greif & Tabellini, 2017). The educational role of the clan revolves around moral and ethical precepts, crucially curbing behaviors that could jeopardize the clan. Embedded within the clan is a cultural ethos brimming with rich and comprehensive ethical standards (Peng, 2004). This ethos instills values such as “see good and do it” and “share joys and sorrows” among clan members, fostering the perpetuation of ethical codes through tangible actions, which, in turn, stimulates the altruistic motivation of individuals.

Second, the clan tradition places significant emphasis on social reputation, encouraging members to uphold and enhance the honor of the clan rather than detracting from it (Watson, 1982). Rooted in the fundamental principle of glorifying the clan, this ethos guides clan behavior, steering it away from actions that may undermine the interests of other clans while striving towards the aforementioned goal of enhancing clan prestige (Xu & Yao, 2015). Additionally, in China, which is characterized by a relational (“RenQing” in Chinese) society (Wang et al., 2008), the extensive network of clan relationships imposes external informal constraints on individuals (Peng, 2004). Members of the clan, especially those with high status, expected to meticulously safeguard their reputation and conduct, as their roles and obligations are documented in the clan's genealogical records. This contributes to a prevalent Chinese “shame culture,” wherein clan members may undergo great condemnation by other elites of the same surname and/or be expelled from the clan if they violate moral rules (Huang et al., 2022). If socially irresponsible and immoral behavior is disclosed, chairpersons may experience difficulties integrating into the local clan group, resulting in both tarnished market reputation and diminished social capital (Chuang et al., 2012). Therefore, by integrating ethical elements of moral constraints and rewards, clan culture fosters a greater willingness among enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities and thus glorify the clan. Ethical norms not only caution clan members to exercise prudence in speech and action through moral sanctions but also offer moral rewards for acting in accordance with virtuous principles.

Third, the foundational clan principle of “unity and reciprocity” underscores the collective responsibility and moral duties that family members owe to one another, fostering a mutual emotional bond that influences resource distribution in a mutually beneficial manner (Peng, 2004), which may also profoundly impact firms’ CSR initiatives. Under the influence of clan culture which advocates for being kind to others and highlights moral obligations to relatives, members often help and support each other through donations, rewards, or private loans. This mutual benefit is rooted in emotional preference. Moreover, clan culture's emphasis on loving one's family and hometown can further embody the clan spirit of general mutual benefit and mutual assistance (Greif & Tabellini, 2017). This supports the transition from a mutual benefit between “small families” to “everyone,” which is critical to building a harmonious society. Zhang (2019) also believed that clan culture emphasizes the harmony of enterprise and social objectives—referring to the potential spiritual motivation for enterprises to be responsible for improving the natural environment and promoting social development. Therefore, entrepreneurs influenced by clan culture's harmonious vision and harmonious society are likely to help and consider others and repay society; this will then lead to their enterprises engaging in more CSR activities.

Furthermore, clan culture is a peopled-oriented culture that represents the ideology of collectivism based on the blood connection. In contrast to Western corporations, which emphasize individualism and personal benefits or losses, clans rely on collectivism as an underlying principle, which emphasizes collective, concerted action and the maximization of common interests; collectivism can be seen as a dominant cultural archetype in its effect on Asian companies (Xiong et al., 2021). In feudal society, resource-sharing activities, were widespread among clan members to defend against natural disasters and foreign enemies. The clan tradition's trend toward collectivism has also been inherited in modern commercial society and affects the allocation process of market resources (Peng, 2004). A collectivism-oriented culture regards the whole society as a collective, which can weaken egoism and strengthen the individual's sense of corporate citizenship (Lin et al., 2022); this is a crucial factor guiding individuals toward solidarity, caring the others, and undertaking social responsibility. As Fei (1998) proposed, the concept of “home” in China is excellent flexibility and does not have strict group boundaries. Identifying family members should be extended to those interested in participating and expressing affection. The influence and scope of clan culture will also gradually extend beyond the family calling for more cooperation in and out of the family. That is also consistent with the spirit of unity and reciprocity. Thus, chairmen who have been deeply influenced by clan culture have stronger collectivism based on “small family” since childhood, which will help them have a strong sense of cohesion and more easily accept collectivism's transition toward encompassing “everyone” in the future. This, in turn, will make them more willing to integrate into social groups and consciously assume the responsibility of being a member of such a group.

Finally, the value of long-term orientation imprinted by a clan culture background leads chairpersons to seek future returns and realize the potential long-term benefits of CSR. The core norm of clan culture lies in perpetuating the lineage bloodline by members (Peng, 2010). Clan members strive to accumulate collective wealth and carry it over through generations to their offspring (Feng, 2013). In short, clan culture embodies the wisdom and value of a long-term orientation, which refers to an inclination to prioritize the long-range implications and effects of decisions that come to fruition after an extended period (Liu et al., 2023). Chairpersons with clan culture imprints tend to prioritize long-term orientation, and believe that significant outcomes often require time to materialize (Brigham et al., 2013). Therefore, they exhibit patience in anticipation of future rewards and acknowledge the necessity of perseverance and sustained effort. Studies have confirmed that CSR can bring long-term returns for firms by securing stakeholder support, reputation effects, resource exchange, and legitimacy (Robles-Elorza et al., 2023; Plaza-Casado et al., 2024). As a result, chairpersons with greater clan culture backgrounds tend to be more committed to investing the required time and resources to ensure the success of CSR activities.

The influence of culture on people is subtle but deep-rooted, especially since childhood. As a form of regional culture, clan culture subconsciously affects chairpersons’ modes of thinking, determines their strategic approaches, and motivates them to act on CSR behaviors. The above arguments also highlight the mediating role that moral principles, unity and reciprocity play in the relationship between clan culture and family firms’ CSR performance. Clan culture with moral principles as an educational resource will stimulate altruistic motivation and a good moral reputation, while the ethos of mutual assistance cultivates a humanistic environment characterized by mutual support and compassion, fostering a harmonious societal perspective. This, in turn, bolsters individuals’ readiness to embrace social responsibility. Consequently, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 A family firm with a chairperson of the board born in an area with a strong clan culture will exhibit higher levels of CSR performance.

Hypothesis 2 Moral principles mediate the effect of clan culture on family firms’ CSR.

Hypothesis 3 Unity and reciprocity mediate the effect of clan culture on family firms’ CSR.

Traditionally, researchers examining the antecedents and consequences of CSR have treated them as an aggregate variable encompassing all of a firm's CSR activities. However, CSR is inherently multidimensional, covering a wide range of activities. Each of these activities has unique characteristics, and a composite CSR score may not fully capture the extent of a firm's CSR engagement (Xu & Ma, 2022). According to Wang et al. (2016) and Al-Shammari et al. (2019), factors such as firm size, geographical proximity, and the importance to stakeholders can influence the visibility and impact of CSR activities. Furthermore, the upper echelons theory suggests that the personal attributes of senior leaders play a crucial role in determining which external stimuli they are most responsive to, how they identify opportunities, interpret task-related discussions, and prioritize stakeholder needs (Reimer et al., 2018). Consequently, a firm's focus on different dimensions of CSR may be shaped by the characteristics of its chairperson.

A firm's CSR can be categorized based on its stakeholders as either internally oriented CSR, such as employee- and investor-oriented activities, or externally oriented CSR, such as philanthropic contributions and community- and environment-oriented activities. These will more easily determine the dynamics of the relationships between a particular CSR dimension and its determinants. Cultural rules determine social trust's characteristics, radius, and depth (Pan et al., 2019). Each society has a trust boundary, leading to greater trust in the people inside the boundaries than those outside. A distinct feature of clan culture is forming short-radius trust (Fukuyama, 1995). Different from the generalized trust environment under the Western city-state system, the impact of clan culture on social trust may be hierarchical: clan culture is conducive to promoting the construction of trust with a short radius—i.e., limited trust (or acquaintance trust) linked by blood and geography. As clans were built upon the principles of cohesion among group members, to promote group cohesion, clans usually set out rules that required members to live in harmony with one another and to help members in need to strengthen mutual trust (Cheng et al., 2021). However, the emphasis of clan culture on group interests may overshadow general trust—that is, external trust (Alesina & Giuliano, 2011). For example, in the case of China, clan members were usually taught not to trust outsiders easily and to exercise caution when socializing with strangers (Feng, 2013). Social trust and interpersonal relationships based on clan culture may show the characteristics of a differential pattern, which promotes differential treatment between those inside and outside the group. This means that the degree of trust and emotional preference for group members will be much higher than for strangers (Peng, 2004).

Additionally, as previously proposed, clan culture is a typical culture advocating for collectivism based on the blood relationship aiming to maximize collective interests and fostering intimate interpersonal connections. Different from the concept of equality and free competition in market culture, one characteristic of collectivist cultures is the tendency to categorize people and groups of people into two broad categories: the in-group and out-group, which results in more significant in-group favoritism among collectivists (Xu & Ma, 2022). Therefore, areas with a strong clan culture are characterized by an acquaintance society, resulting in their valuing trust building with insiders, internal reciprocity and collaboration, and offering support to insiders to maximize collective interests (Penny et al., 2003). Compared with external stakeholders, such as the community, stakeholders directly related to the enterprises have a closer relationship with the chairpersons and are more likely to be classified as broad family members beyond clan kinship (Du, 2019). Due to this trust and emotional asymmetry embedded in the clan culture, chairpersons with a strong clan concept are more willing to help and care for those who are more closely related to or belong to the same group and will show higher levels of trust, favor reciprocity, and feel a greater sense of responsibility towards internal stakeholders. This includes exhibiting prosociality among in-group members and assuming more internally oriented CSR.

Finally, another explanation may be close to the clan tradition of resource pooling. Common property ownership is an essential characteristic of clan organizations. Clans have a long tradition of resource pooling and sharing among their members (Fukuyama, 1995). They usually pooled resources to establish a variety of common properties, mainly in the form of land and used the yields to provide public goods. For example, charity land was used to support the poor; ritual land was used for ancestor worshiping and offerings; and education land was used for sponsoring children's education (Pan et al., 2019). However, traditional clan rules discouraged selling property to those outside the clan (Cheng et al., 2021). For instance, historically, clans in China strictly prohibited selling common properties outside. Even for privately owned properties, owners were required to first find buyers inside the clan, and selling to outsiders was permitted only if no other clan members were interested in purchasing (Fei, 1998). To some extent, this cultural norm helps facilitate resource pooling among family members (Greif & Tabellini, 2017). Based on the concept of sharing internal resources and protecting common property, as the allocator of corporate resources, chairpersons of the board with strong clan culture will regard corporate resources as internal resources created by themselves and internal stakeholders together and, thus, prioritize sharing to them, with external stakeholders only considered after meeting the internal distribution requirement. In other words, compared with external responsibilities, these chairmen prioritize allocating enterprise resources to internal stakeholders and practicing internal responsibilities. These arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 Clan culture has a more significant impact on internally oriented rather than externally oriented CSR.

We select all family companies listed on the A-share Main Board, Small- and Medium-sized Board and Growth Enterprises Market Board for the period 2006 to 2020 as Chinese-listed companies first disclosed CSR information in 2006. Data on family firms’ CSR measures were obtained from Hexun.net. The China Stock Market and Accounting Research and Wind Databases provided financial and industry affiliation data. The intensity of Clan Culture is measured by city-level genealogy density (Huang et al., 2022). Genealogy-relevant data were obtained from the China Family Panel Studies Database (CFPS) of Peking University and the General Catalogue of Chinese Pedigree2. The data on surname concentration in cities across the country was derived from the data of the national census in 2005.

This study excludes financial firms and firms with missing information. Because some enterprises fail to disclose CSR reports, some of the CSR dimensions of these firms could not be evaluated and were thus assigned a value of 0. Therefore, this study eliminates samples with a stakeholder dimension assigned 0. Additionally, this study controls for outlier effects by trimming all variables in the top and bottom 1%. This procedure led to a final sample of 6,937 firm-year observations with non-missing variables.

3.2Measures3.2.1CSR scoreIn China, CSR ratings from Hexun.com, a financial information data analysis website, are widely accepted3. Based on stakeholder theory, Hexun.net developed an index assessing CSR for five stakeholder groups: investors, employees, community, customers and suppliers, and the environment. According to the difference in the importance of the responsibilities of each stakeholder in different industries, Hexun.com also constructs heterogeneous weights for these five stakeholders in different sectors. Following Xu and Ma (2021) and Zhang (2022), the weighted average scores for CSR provided by the Hexun website constitute our CSR proxy.

3.2.2Clan cultureGenealogies serve as primary repositories of clan culture, documenting the historical and cultural evolution of each clan (Greif & Tabellini, 2017). The abundance of genealogies reflects the frequent historical engagements of local clans and, consequently, the depth of clan tradition. Therefore, areas with a rich cultural ambiance tend to preserve more genealogies (Zhang, 2017). Despite relocation, individuals often retain significant cultural disparities originating from their heterogeneous regions of origin (Pan et al., 2017). Recent research suggests that chairpersons may wield a more substantial influence on firm decisions than CEOs. Thus, following Greif and Tabellini (2017), Pan et al. (2019), Zhang (2020), and Wang et al. (2022), this paper employs a genealogy density measure of chairpersons’ native places—specifically, the number of available genealogical volumes per million people—to measure the intensity of clan culture (Clan).4 To mitigate outlier effects, clan culture is measured by the logarithm of 1 plus the number of genealogies per million individuals.

Due to the significant changes in the administrative regions after the founding of the People's Republic of China, this paper counts the number of genealogies in various cities from the Song Dynasty to 1949 using the CFPS database and the General Catalogue of Chinese Pedigree. We manually arranged the genealogical data before liberation and matched it with the current cities. Additionally, considering that China's large-scale population flow and rapid economic growth occurred after Deng Xiaoping inspected Guangdong and other places in 1992, this study follows Pan et al. (2019) by using the urban population in 1990 to standardize the number of genealogies and obtain the number of genealogies per million people. Because the population of each region in 1990 can represent the number of its aborigines, this study identifies the historical record of local clan culture and avoids the endogenous problem of reverse causality.

3.2.3Control variablesTo control for various factors confining the relationship between clan culture and CSR performance, this study included a series of the firm-, region-, and chairperson-level controls in its tests, which is referenced to Huang et al. (2022), Xu and Ma (2022), Bothello et al. (2023) and Wang et al. (2023b). We briefly discuss these variables below, and their detailed definitions are provided in Appendix A. The firm-level control variables include size (Size), return on assets (Roa), leverage (Lev), age (Age), market-to-book ratio (MB), and cash flow from operations (Cash_flow). For the chairperson-level controls, this study includes the age (Cage) and educational background (Cedu) of the chairperson, the proportion of outside directors (Outdir), the ratio of the chairperson's holding shares (Cshare), an overseas experience dummy variable (Coversea) and a duality dummy variable (Cduality).

For region-level controls, this study includes the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) and the level of marketization of the province in which the company is registered (Market). Additionally, we also control for the degree of regional agricultural development (Gdppri), which is measured by the ratio of the primary industry to the GDP; because clan culture was bred in a traditional agrarian society, the more developed the agriculture is, the stronger the traditional cultural atmosphere may be. Zhang and Ma (2017) found that clan culture mainly appeared in Han-inhabited areas and shifted with the migration of this nationality. Therefore, this study adds a dummy variable (Minority), representing whether the firm is registered in a minority region, as a control variable. Moreover, as another essential informal system, religion not only affects its believers but is also integrated into Chinese traditional culture, thus exerting a subtle influence on the shaping of Chinese values (Du et al., 2014). Referring to Du et al. (2014), this paper uses the temples within 200 kilometers of the chairpersons’ native places as the proxy variable of religious belief (Religion) in the regression.

3.3Research modelThis study uses regression analysis to test the effect of clan culture on the level of CSR. The assumptions underlying the regression model are tested for multicollinearity based on a correlation matrix and the variance inflation factor. None of the variables have a variance inflation factor greater than 5, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem in interpreting the regression results. The regression is specified as follows:

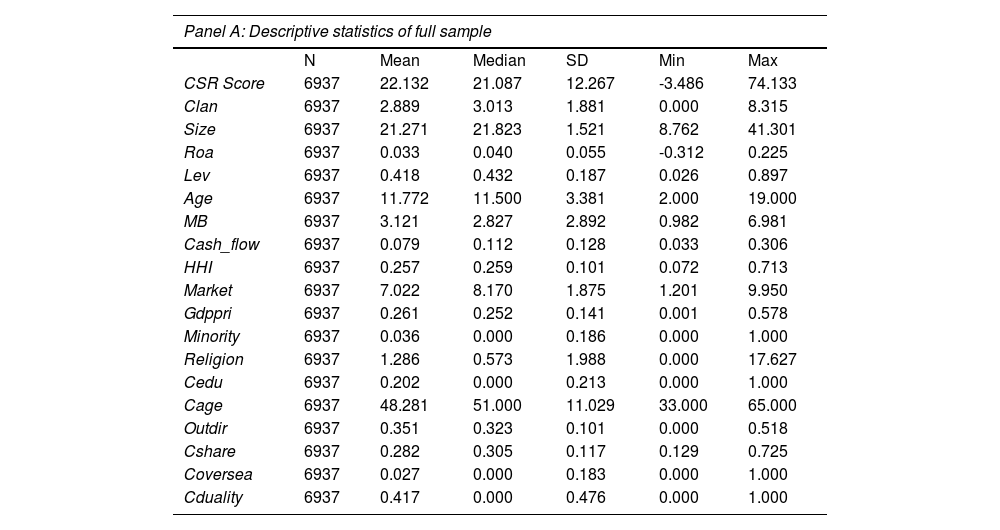

where CSR Score is defined as a firm's overall CSR performance and all aspects of CSR. The regression includes a firm's CSR Score in the previous year to avoid any forward-looking bias, as previous studies suggested that CSR activities are serially correlated (Tang et al., 2015). The other control variables are as previously discussed. To reduce the heteroscedasticity of panel data, particularly the influence of temporal correlations and cross-section correlations that may appear in the text data, this paper uses clustering robust standard error by firm clusters to correct t-values and estimated it using the fixed model to control for any common trends in the CSR Score over time and between industries.3.4Descriptive statisticsPanel A in Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the key variables used in the study's primary test. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to ensure that extreme values do not influence the results. The variable CSR Score has a mean of 22.132 and a standard deviation of 12.267. The minimum value of Clan is 0; the maximum value is 8.315; the mean value is 2.889; and the standard deviation is 1.811. This suggests great differences in the clan cultural atmospheres between cities. The other variables’ descriptive statistics appear in reasonable ranges and are comparable with those in prior studies (e.g., Xu & Ma, 2022).

Descriptive statistics.

According to the median genealogical density, this paper divides the samples into areas with strong and weak clan cultures and compares the descriptive CSR statistics between the two groups. Panel B in Table 1 reports the results. The t-test and Wilcoxon z-test results indicate that the levels of CSR for chairpersons’ native places, being areas with a strong clan culture, are significantly higher when compared with the results for other firms. Thus, the descriptive statistics initially verify Hypotheses 1.

Table 2 reports the main variables’ univariate correlations. The correlation matrix demonstrates that clan culture (Clan) positively correlates with CSR performance (CSR Score). It is also noteworthy that CSR Score negatively correlates with leverage (Lev), firm age (Age), the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), the level of agricultural development (Gdppri), the duality of the CEO and chairman (Cduality), and ethnic minority (Minority). In contrast, it is positively correlated with all other variables.

Correlation matrix.

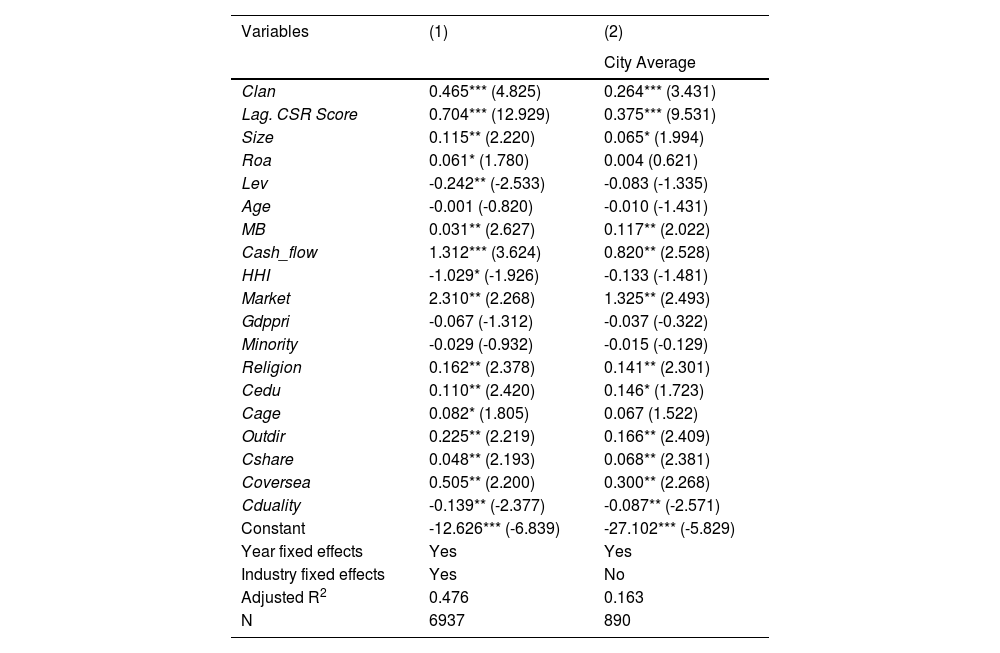

Hypothesis 1 predicts a positive relationship between clan culture and CSR performance. Table 3 displays the results of regressing the hypothesized variables on the level of CSR performance. To alleviate a possible cross-sectional correlation between the firms and ensure an unbiased consistency in the estimates, this paper adjusts the t value by firm clustering (Petersen, 2009). The coefficient of Clan is 0.465 in Column (1), which is significant at least at the 5% level, suggesting that a family cultural atmosphere is significantly and positively associated with firms’ CSR performance. Thus, chairpersons who have been exposed to clan culture since their childhood in their hometowns will stimulate their potential sense of social responsibility to others and lead to their companies’ better CSR performance; this supports Hypothesis 1. As Guiso et al. (2006) proposed, cultural influence changes slowly. An individual's family culture deeply affects their psychology, values, and behaviors during childhood and continues throughout their entire lifetime.

Regression results: Clan culture and CSR performance.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

Additionally, considering that the independent variable representing clan culture is a city-level regional variable rather than a firm-level variable, this paper divides the sample by region according to the chairpersons’ native cities and combines all firms belonging to the same city in the same year into one observational value. By calculating the mean CSR score and control variables for each city in different years, this study uses regional clan culture to regress the average CSR score for each city. Column (2) reports these results. The results show positive, significant coefficients for the independent variable at the 1% level (0.264). All these results are consistent with Hypotheses 1.

Furthermore, all models’ coefficients of CSR Score in the year (t-1) are positive and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that a firm's prior CSR performance significantly impacts its current CSR performance. Size, Roa, MB, Cash_flow, Cedu, Cage, Outdir, Cshare, Coversea, and Market all significantly and positively affect family firms’ CSR, but the coefficients of Leverage, HHI, and Cduality are all significantly negative which are consistent with the previous literature, such as Xu and Ma (2022) and Wang et al. (2023b). However, the coefficients of Age, Gdppri, and Minority are negative but not significant.

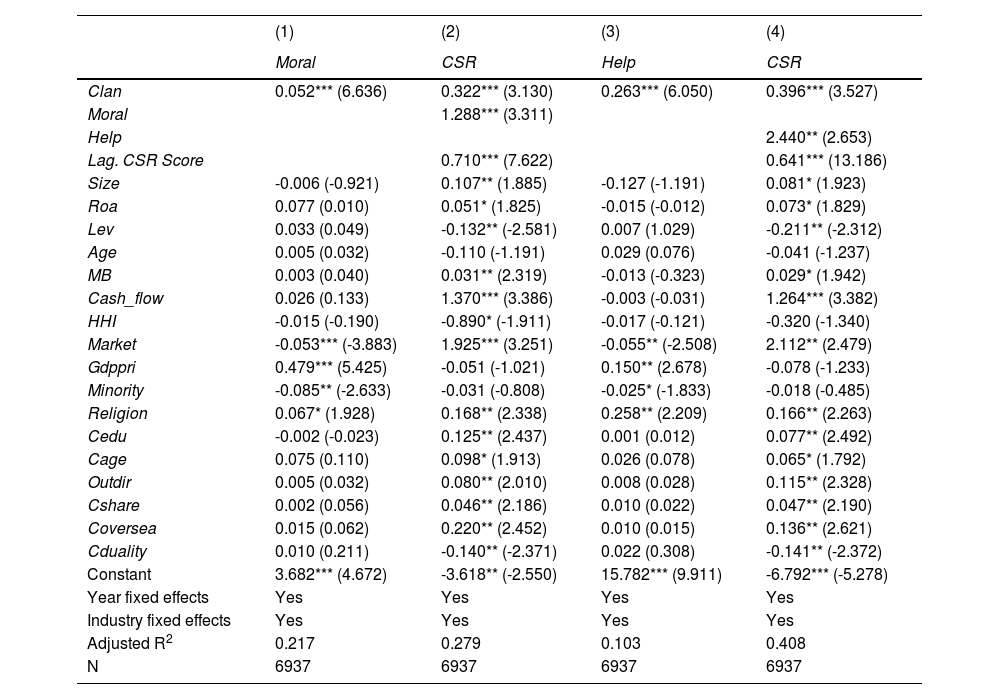

4.2The mediating effects of moral principles and unity and reciprocityThe previous results show that clan culture contributes to CSR performance; however, the internal mechanism needs to be clarified. As mentioned before, this paper believes that the concepts of moral principles, unity and reciprocity play mediating roles between clan culture and family firms’ CSR. The following mediating effect test procedure proposed by Wen et al. (2004) is used to examine the internal mechanism.

- (1)

Moral principles. This paper believes that morality can play a mediational role in clan culture's effect on CSR, setting the Shame Feeling Index (Moral) as a proxy accordingly. The following question about moral concepts is selected from the Chinese General Social Survey data (CGSS, 2013)5 to measure shame: “What do you think of the severity of the lack of shame in current society?” The score ranges from 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating less shame. To better understand the mediational role of ethics, this paper reverses the index score, meaning that the higher the score, the greater the scandal and, thus, the stronger the social ethics atmosphere. Columns (1) to (2) show the results. The Clan (0.052) coefficient is positive and significant at the 1% level in Column (1), suggesting that the stronger the regional clan culture, the stronger the local residents’ general sense of shame, and the more likely they are to abide by moral norms. Consistent with the prediction, a significantly positive relationship exists between Clan, Moral, and CSR performance in Column (2), indicating that morals can promote the active fulfillment of CSR and play a partial mediating role in clan culture affecting CSR.

- (2)

Unity and reciprocity. This paper believes that “unity and reciprocity” is another mediating variable in clan culture affecting CSR and accordingly sets the Helping Index (Help) as the proxy. The following question is selected from the CGSS (2013) to measure interpersonal communication: “Do you agree that others will always find ways to get an advantage, whether intentionally or unintentionally?” The score also ranges from 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating a stronger selfishness. Thus, it can be inferred that when others encounter difficulties, unpaid social responsibility behaviors are challenging to achieve, meaning that the concept of mutual assistance is weak. Similarly, the score of Help is also reversed; the higher the score, the more emphasis is placed on mutual assistance between people. The results again document positive and significant coefficients for Clan (0.263) in Column (3) Table 4. The coefficients of Help and Clan in Column (4) are also significantly positive, at least at the 5% level, suggesting that mutual assistance also has a partial mediational effect.

Table 4.Regression results: analysis of internal mechanism.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

Considering that investors are the owners and belong to the core internal personnel of the firm, possessing a very close relationship with the object of this paper (chairman of the board), while consumers and suppliers are only upstream and downstream partners of the enterprise and not insiders involved in its operation rise. Thus referring to Al-Shammari et al. (2019), this paper further classifies a firm's CSR initiatives directed toward the external stakeholders are divided into community-, environment-, consumers- and suppliers-oriented activities, while employees and investors comprise two relevant dimensions to capture the internal CSR of the firm. The scores for each of the two CSR aspects are recounted to test Hypothesis 4 to examine further the effects of clan culture on each of these aspects. To compare the differential influence of clan culture on internal and external responsibilities, both independent and dependent variables are standardized before the regression. Column (1) in Table 5 displays the regressions of various clan cultures on external CSR, while Column (2) reports the results for internal CSR.

Regression results: Effects of clan culture on external and internal CSR.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

Consistent with the previous findings, a significant, positive relationship is found between clan culture and whether internally or externally oriented CSR performance. However, the coefficient for clan culture is smaller and less significant for externally oriented CSR (0.187) than internally oriented CSR (0.330). This suggests that clan culture will better relate to internally oriented CSR activities, confirming what is proposed in Hypothesis 4. To further examine the significance of the difference between the two regressions, the Suest test is used. The p-value is 0.0004 and significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the difference in the coefficients of clan culture on external and internal CSR is statistically significant, further confirming that the clan culture experienced by chairpersons since childhood can exert a more significant influence on internal CSR than external CSR.

4.4Further analysisTo further explore the boundary of clan culture's influence on family firms’ CSR, this paper explores five environmental factors that may affect clan culture and social responsibility of family firms as follows:

- (1)

Will there be differences in clan culture's influence when the chairperson operates locally and in other places?

A clan, a social unit formed by individuals tracing their lineage to a common ancestor, typically exhibits concentrated presence in specific regions, rendering clan culture inherently regional. Despite increased mobility facilitated by advancements in transportation, established clan organizations persist in their geographical locations across generations. Migrants, while integrating into local clan networks through recognition of clan culture, experience less influence from the moral education and constraints inherent to the local clan culture due to the absence of verifiable blood ties (Pan et al., 2019). Additionally, even if the actual controllers established elsewhere uphold strong clan affiliations, the moral environment tends to be weaker compared to their native regions, consequently diminishing the influence of hometown clan culture. Therefore, this paper introduces the variable Native, a dummy variable equal to 1 if the actual controller operates in his native place and 0 otherwise, along with an interaction term, Clan×Native. The coefficient of the interaction in Column (1) of Table 6 is significantly positive, suggesting that when the chairperson operates the enterprise in his native place, the positive impact of his clan concept on CSR has been strengthened.

Table 6.Regression results: further analysis.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively. The results of control variables are consistent with the previous findings. Due to the limitation of the number of words, the results of control variables are omitted in this table.

- (2)

Will demographic changes affect the development of clan culture?

Since Deng Xiaoping's southern tour in 1992, China has witnessed substantial population movements, leading to significant shifts in local cultural environment and social networks. To explore the impact of demographic changes, this study adopts the population in 1990 as a baseline, assuming it represents the original residents of each city. Utilizing the national population growth rate of 17.3% from 1990 to 2010, the population of each city during the study period is estimated, assuming no inter-city population mobility. Subsequently, two proxy variables, Popu_rate and Popu_shock, are indroduced to capture population shocks. Popu_ rate is measured by the actual population of each city in the current year divided by the estimated population, with the variable of each year divided into tri-sectional quantiles. Thus, Popu_shock equals to 2 when Popu_rate falls within the highest third, 1 when it lies in the middle third, and 0 when it falls within the lowest third. Furthermore, an interaction term, Clan×Popu_shock, is included, and its coefficient in Column (2) of Table 6 found to be significantly positive at the 5% level (-0.107), suggesting that changes in population structure indeed exert a noteworthy impact on the economic consequences of clan culture.

- (3)

Is there any difference between male and female chairpersons affected by clan culture?

The ethical principles, trust preferences, and values of reciprocity ingrained within clan culture significantly shape the values of chairpersons. However, individual traits of chairpersons also play a pivotal role in shaping their values, thereby impacting enterprise decision-making processes (Xu & Ma, 2022). Gender bias is particularly salient within Chinese clan tradition (Murphy et al., 2011), which historically revolve around male genetic lineage. This enduring gender inequality within clans may have attenuated the influence of clan culture on women. Specifically, women often assume membership in their husband's family post-marriage, complicating their emotional attachment to individuals sharing their surname. Therefore, chairpersons’ gender may also affect their preferences and cognitive processes, subsequently influencing CSR decision-making. This study introduces a gender dummy variable (Female), assigned a value of 1 if the chairperson is female and 0 otherwise. The coefficient of Clan×Female in Column (3) of Table 6 is significantly negative at the 5% level, indicating that gender bias inherent in clan traditions indeed diminishes the impact of clan culture on CSR decision-making.

- (4)

Is a small or a big clan more influential?

Compared with small clans, large clans exhibit deeper historical roots, superior organization, and more pronounced social norms (Xu & Yao, 2015). Chairpersons originating from large clans are more likely to encounter familial ties within the market. The entrenched brand of clan culture experienced since childhood in large clans facilitates these chairpersons’ perception of the surrounding cultural atmosphere and enhances emotional and identity bonds between individuals, even when they relocate from their hometown. This paper tries to judge the power of the chairperson's clan by counting whether the chairperson has an ancestral temple with the same surname in his native place. Up to now, only large clans, which typically hold greater influence in the region, possess ancestral temples. This paper introduces the variable Bigclan as a dummy variable, equaling 1 if the chairperson has an ancestral temple with the same surname in his native place and 0 otherwise, and an interaction variable Clan×Bigclan is added. The coefficient of the interaction in Column (4) of Table 6 is significantly positive, suggesting that chairpersons from powerful clans are more susceptible to the influence of local clan culture This, in turn, strengthens the positive impact of the clan concept on CSR.

- (5)

Will formal institutions weaken the influence of clan culture?

As a major informal institution, culture and institutions might complement each other or act as substitutes, contrasting each other (Huang et al., 2022). To comprehensively grasp the impact of clan culture on CSR, formal institutional frameworks cannot be disregarded. As noted in the previous literature, it has been well accepted that the economic and institutional context is the main determining factor of CSR behaviors. This paper does not contend that informal institutions or cultures embedded in clans outweigh formal institutions in importance. Rather, it underscores the significance of informal institutions or culture, particularly in contexts where formal market-supporting institutions are underdeveloped (Zhang, 2020). Essentially, clans act as substitutes for ineffective formal institutions during China's transitional phases. To examine whether the effect of clans wanes with the advancement of formal market-supporting institutions, an interaction term between the clan variable and the quality of local formal institutions (Clan×Formal) is added. Previous studies show that regions with robust economic institutions tend to attract higher levels of foreign direct investment (Du et al., 2008). Following Zhang (2020), the amount of foreign capital investment in each prefecture serves as a proxy for the quality of local formal institutions (Formal). The coefficient of the interaction term in Column (5) of Table 6 is significantly negative (-0.518), suggesting that the role of clans diminishes as formal institutions progress. This evidence underscores the interdependency of informal institutions, such as culture, on corporate decision-making, contingent upon formal institutions or the political environment, which explains why certain countries or regions with similar cultural traditions exhibit considerable differences in economic performance, as exemplified by North Korea and South Korea.

(1) Endogeneity and omitted variables

A key problem in regression analyses involves overcoming the endogeneity of variables, which may occur with omitted variables and simultaneous causality. Clan culture is a regional cultural environment that cannot be affected by enterprise decision-making. Therefore, this paper primarily analyzes the endogeneity caused by omitting variables that may affect both independent and residual terms. A two-stage least-squares method is employed to ensure the robustness of the results to endogeneity. The per capita rice planting area in 1990 (Crop)6 and the number of wars during the Song Dynasty (War)7 are used as instrumental variables.

The clan evolved from the development of an agricultural economy, and rice planting often requires the cooperation of farmers to conserve water, sow, and harvest. Thus, such a production model requires small social groups (such as clans) as the basic unit, providing natural conditions for forming and disseminating clan culture (Wen, 2001). As a result, the more dependent on rice planting, the stronger the clan culture. Considering that the region's per capita rice planting area was more created by the natural environment, which did not directly affect the CSR activities of currently listed companies, the per capita rice planting area in 1990 of chairpersons’ native places at the city level is an appropriate instrumental variable.

Additionally, every large-scale population migration in history will lead to the transfer of cultural centers. The latest large-scale population migration can be traced back to the Song Dynasty, and changes in the geographical pattern of clan culture distribution (Zhang & Ma, 2017). Therefore, the more wars that occurred during the Song Dynasty, the more unfavorable situations were for the development of clan culture. Considering that the number of battles in the Song Dynasty was mainly related to the ancient social and political environment and cannot directly affect the daily behavior of current enterprises, the number of wars that had been fought during the Song Dynasty in the chairpersons’ native places at the province level is also an appropriate instrumental variable.

As evidenced in Table 7, the coefficient of War is significantly negative, the coefficient of Crop is significantly positive at the 1% level in Columns (1), and the Sargan test scores are 0.165 (p = 0.731). The F-values of the first stage is 457.693, which is far greater than 10, suggesting that the two instruments are effective and highly correlated with the endogenous variables. The results of the second-stage regression reported in Table 7 are consistent with the main findings.

(2) An alternative proxy for variables

Robust tests: endogeneity.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

Although Hexun has developed a measure of firms’ CSR performance, the measurement process may be insufficiently objective. Thus, We also examine the robustness of its results using Rankins’ CSR ratings, which are provided by an independent third-party organization. Unlike Hexun.com, Rankins evaluates CSR entirely based on CSR reports, and there is no difference in the weight of each index. Nevertheless, like Hexun, Rankings is one of the two most widely used corporate social responsibility (CSR) ratings in research on CSR in China's capital market (Zhong et al., 2019). Column (1) of Table 8 illustrates the results. Moreover, some scholars believe that stakeholders are generally referred to as non-shareholder stakeholders. Thus, this paper removes the responsibility toward investors from the Hexun CSR score for further analysis. The results are shown in Column (2) of Table 8.

Robust tests: alternative proxy for variables.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

In addition, the second set of robustness checks is to see whether the main results are sensitive to different measures of clan culture intensity. Samples with a clan culture level of 0 are deleted first. One potential concern in measuring clan culture is the date of genealogy compilation. China notably suffered dozens of wars during the late Qing dynasty and the Republic of China period. The disorder during these periods affected the tendency and ability of local people to compile genealogies. To check the robustness of our results, we separately employ the number of genealogies written from the Song Dynasty to 1912 (Clan_prc) and 1850 (Clan_ow) to measure the local intensity of clans because the Republic of China (PRC) was founded in 1912, and Year 1850 is the last year of the reign of Qing's Emperor Dao-Guang, during whose dominion occurred the famous Opium War (1840–1842). The outbreak of this war plunged China into a hundred years of war. We also focus on the clans complied after 1978, as the spatial distribution of clans might have changed given that such traditional activities were nearly banned by the Chinese Communist Party during the 1949-78 period. Thus, the statistical ranges of the genealogies to two other periods, from the Ming Dynasty to 1990 (Clan_m) and from the Qing Dynasty to 1990 (Clan_q), are also adjusted, respectively. Similarly, taking the population in 1990 as the benchmark, clan culture is measured by the logarithm of the number of genealogies per million people in the four periods. Regardless of which method replaces the independent or dependent variables’ measurements, the findings further reinforce the earlier evidence.

(3) The adjustment of the sample

As previously mentioned, there was large-scale population mobility in China in the late 1990s, which had a certain impact on the inheritance of local clan culture. According to the results of the Popu_rate calculated above, this paper further eliminates the sample in which the chairperson's native place or firm's registration place belonging to the migrant population had an impact higher than the median. Column (1) of Table 9 reports the results. Additionally, since historically clans were less concentrated in large metropolitan areas, one may suspect that our finding of a positive association between clan culture intensity and CSR is driven mainly by firms located in the big cities. To address this concern, in Column (2) of Table 9, we exclude the samples whose chairpersons’ native places are the four major cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen.

Robust tests: the adjustment of sample.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

Furthermore, China has 56 ethnic groups, which include the Han Chinese and 55 other ethnic minorities. Since clan culture is mainly prevalent among the Han Chinese, it may be inappropriate to include these minority-concentrated regions in our analysis (Zhang, 2020). As another robustness check, we exclude the five ethnic autonomous regions: Guangxi, Tibet, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang from our estimation sample and report the results in Column (3) of Table 9. Finally, there have been significant economic and cultural development differences between Eastern and Western China. China's clan settlement also shows the characteristics of greater prosperity in the South than in the North. To avoid the influence of the inherent regional differences, this paper also eliminates the samples from western provinces, such as Gansu, Shanxi, Guizhou, Xinjiang, Yunnan, and Qinghai. However, regardless of what kind of sample is used, the previous findings remain robust.

(4) Sample Selection Bias

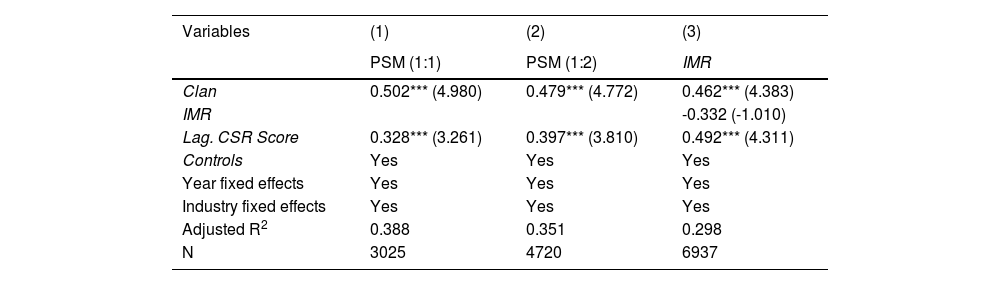

This paper may also have the problem of sample self-selection, meaning that CSR differences exist between firms with strong and weak clan concepts. Therefore, by quartile Clan, the sample enterprises in the highest quartile (firms with the strongest clan culture) are retained (treatment group), and the remaining three-quarters are excluded. This paper also uses the propensity score matching (PSM) method and uses a one-to-one and one-to-two nearest neighbor propensity score matching with a replacement on a set of observable firm characteristics. The results from Columns (1) to (2) of Table 10 further confirm the previous findings. Additionally, this paper uses a Heckman two-stage model to calculate the Inverse Mills Ratio (IMR) to avoid sample selection error. The IMR is added to Model (1) to perform another regression. The coefficients of Clan are still significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that the main conclusion of this paper is still robust after considering the possible sample selection problem.

Robust tests: sample selection bias.

The t statistics adjusted by firm clusters are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10, 5 and 1% levels, respectively.

The clan culture, a distinctive native culture with a rich historical legacy, is widespread not only in China but also in many other Asian countries (Liu et al., 2023), retaining its significant influence in contemporary society. Anchored in upper echelons theory and imprinting theory, this study aimed to investigate the impact of clan culture on Chinese family firms’ CSR performance to explore the cultural drivers behind CSR behaviors from a regional culture perspective. Utilizing hand-gathered Chinese genealogical data, the findings reveal that CSR performance is positively associated with the regional clan culture of chairpersons’ native places. Specifically, the moral precepts and ethos of solidarity and reciprocity ingrained within regional clan culture emerge as two potential mechanisms underpinning the influence of clan culture on CSR practices.

The existing literature on CSR motivations has predominantly focused on the formal determinants of CSR (Al-Shammari et al., 2019). However, scholars increasingly recognize that the strategic decision-making, survival, and growth trajectories of Chinese firms, particularly those in the private sector, are deeply entrenched in the local cultural milieu. Therefore, comprehending cultural-specific factors is essential in determining CSR decision-making and the success of Chinese firms. This study bridges this gap in the literature by introducing a novel cultural construct—clan culture within the Chinese context. This paper presents empirical evidence that clan culture, as a distinct historical legacy, shapes the lasting pattern of individual values. And this paper not only contributes to the discourse on the cultural drivers of CSR but also enriches the broader strand of literature that examines the consequences of ethnic groups (Munshi, 2019).

This paper further elucidates the role of clan culture in CSR performance through institutional logic mechanisms. Institutional logic refers to “the social construction and historical model of material practices, values, and rules, which can shape cognition and behavior” (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999). Clan culture embodies a distinctive institutional logic that influences firms through informal constraints, persisting across generations and deeply ingrained in individual values, thereby influencing their behavior and strategic decision-making (Peng, 2004). Within a cultural context, clan organization molds individuals’ cognition and behavior through robust moral bonds and reputation, and kin-based morality fosters values such as insider loyalty and collectivism (Greif & Tabellini, 2010); this then enables individuals to act in accordance with clan rules and regulations. It is also noteworthy that the findings of this paper do not inherently imply that historical kinship-based clans surpass modern judicial system; rather, they likely complement each other instead of being mutually exclusive.

Moreover, our results demonstrate that chairpersons embedded in a strong clan culture tend to prioritize internal over external CSR activities, indicating that a perceived clan culture encourages a more favorable disposition towards insiders. Previous research has predominantly relied on aggregated CSR measures; however, disaggregating CSR into its components not only responds to the growing calls to unpack the dimensions of CSR (Wang et al., 2016) but also validates the short-distance character of clan culture. It deepens the understanding of the cultural connotations of the clan and the strategic motivation behind social responsibility by suggesting that regional cultural factors should be underscored to elucidate not just the extent of a firm's CSR involvement, but also the specific types of CSR initiatives it should emphasize, thereby extending the findings of Zhang et al. (2023). CSR should be viewed as a multi-dimensional construct, and studies utilizing aggregate measures may fail to capture its full richness and complexity. We argue that conceptualizing CSR strategies as inherently multi-faceted explains the divergence among firms in both their CSR levels and the particular dimensions of CSR they prioritize.

Additionally, this paper contributes to the refinement of both the upper echelons theory and imprinting theory. Scholars focusing on the upper echelons theory have recently made notable progress in capturing the essential chairpersons’ characteristics of psychology and moral personality rather than their demographic indicators (Tang et al., 2018; Ng & Sears, 2020). By examining chairpersons' moral values through the lens of regional clan culture, this research indirectly adds to this relatively new but burgeoning field of inquiry. Moreover, while much existing research highlights how imprinting occurs through individual experiences or acquired knowledge, such as exposure to poverty or military service, it often overlooks the imprinting influence of culture (Zhu et al., 2023). In fact, culture exerts a subtle yet enduring impact on individuals' fundamental values across all facets of life, transcending specific situations. This paper proved that clan culture has a profound impact on their subsequent lives by permeating and shaping the long-term oriented values of people during their childhood, which not only corroborates prior findings on the influence of clan culture and family imprintings on corporate behavior but also broadens the scope of imprinting theory from the perspective of clan culture, thereby enriching the context in which imprints are formed (Liu et al., 2023).

More importantly, prevailing research on imprinting's persistence often assumes a consistent impact (Marquis & Qiao, 2020). Yet, the enduring effect of imprints can be influenced by dynamic external circumstances. This paper further identifies five environmental factors capable of either reinforcing or eroding imprinted values, thereby moderating the influence of clan culture on CSR practices. The findings reveal that the imprinting effect of clan culture is more pronounced among locally operating entrepreneurs or those born into sizable clans. Conversely, factors such as population mobility, formal institutional development, and the gender composition of chairpersons weaken the sway of clan culture. These findings not only advance our understanding of the contextual boundaries shaping imprint persistence by revealing how external environments, familial influences, and individual characteristics create a variation in imprint persistence (Marquis & Qiao, 2020; Marques et al., 2022; Pasamar et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023) but also confirm the complementarity of formal and informal systems.

In response to these empirical results, we offer three management practice insights. First, integrating clan culture into business education can foster sustainable development. Currently, sustainable education has been incorporated into educational strategies, requiring students to build competences that support sustainable development (Martín-Peña et al., 2023). Our study underscores the viability of blending clan culture with business education, demonstrating its promotion of sustainable development behaviors. Second, the synergistic interplay of clan culture and formal systems can drive local economic development. While the Chinese government primarily focuses on attracting foreign talents and enterprises, local clan members boast robust social networks and a deep-rooted local identity. The government should fully explore the value of local clan talents and optimize resource allocation efficiency of local clan members. While supporting the development of local enterprises, it should reasonably maintain a dynamic equilibrium between attracting foreign talent and retaining local expertise. Third, combine the cultural characteristics of clan-limited trust with the management of firm social relations. Internally, integrating clan culture into the construction of corporate culture and leveraging the moral code and core values of the clan to enhance the cohesion between the firm and insiders such as shareholders and employees, can improve the internal governance of the enterprise. Externally, as trust in clan culture shows an uneven order pattern centered on “self”, promoting the concept of solidarity and reciprocity within clans to the whole society and building a culture of trust in modern contractual society is an important guarantee of sustainable development (Zhang & Chen, 2023).

This study has some limitations that open avenues for further research. First, the analysis retrieved data from listed firms in China. Although clan culture can be seen worldwide, it is most noticeable in Asian countries. However, significant variations exist in clan culture across different Asian nations. For instance, India's caste system exhibits a pronounced hierarchical structure among castes, while Korea's chaebols, stemming from family-owned enterprises and evolving into major conglomerates, typically possess significant economic power and have tight ties with the Korean government. Those are different from the characteristics of Chinese clans and warrant deeper investigation within the context of Asian clan cultures. Hence, future research could enhance the generalizability of findings by incorporating samples from diverse countries or cultural backgrounds. Second, due to data limitations, this paper utilized city-level clan culture as a proxy to investigate the issue of CSR by exploring the mechanism of regional clan culture on chairperson moral values. However, substantial cultural disparities exist even among families within the same geographic area (Marques et al., 2022). Future research could delve deeper into clan culture at the chairpersons’ level. Third, as a cultural variable, clan culture has severe limitations. Clan culture is not only an inherited cultural variable but also encompasses other vital logic due to its pluralistic nature. Furthermore, culture can impact economic outcomes (Guiso et al., 2006) through mechanisms other than clan protection logic. Thus, subsequent work should explore alternative mechanisms linking clan culture and CSR, including gender. Since gender diversity has been shown to positively influence CSR activity (Díez-Martín et al., 2023), gender itself may affect the perception of the key values of clan culture as well as the sense of identity and belonging to the clan, which ultimately influence the relationship between clan culture and CSR. Another caveat is from a dynamic perspective, that clan culture may exert time-varying effects on firm behavior, and these are not thoroughly examined in this paper due to data limitations. Integrating clan culture with firms’ dynamic operational capabilities could contribute to enhancing local legitimacy over time, which can be integrated into research on how firms can improve their dynamic competencies to to navigate institutional pressures and evolving international market conditions (Rivero-Gutiérrez et al., 2024).

Compliance with Ethical StandardsWe declare that we have read and approved the final manuscript, and due care has been taken to ensure the integrity of the work.

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support provided by the Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (GD23CGL05), National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515011362; 2022A1515012132) and Ministry of Education, Humanities and Social Science Research Projects of China (21YJA630102).

CRediT authorship contribution statementShan Xu: Writing – original draft, Validation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jiaxian Guo: Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

| Independent variables | |

|---|---|

| Clan | Ln (1 + the number of genealogies per million people of a chairperson's native place at the city level) |

See https://www.pwccn.com/zh/entrepreneurial-and-private-business/nextgen-survey/nextgen-survey-2022.pdf

Wang, H. M. (2009). General Catalogue of Chinese Pedigree. Published by Shanghai ancient books publishing house. China: Shanghai. China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) is a nationally representative, annual longitudinal survey of Chinese communities, families, and individuals launched in 2010 by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University, China. The CFPS is designed to collect individual-, family-, and community-level longitudinal data in contemporary China. The studies focus on the economic, as well as the non-economic, wellbeing of the Chinese population, with a wealth of information covering such topics as economic activities, education outcomes, family dynamics and relationships, migration, and health. http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/english/data/cfps/index.

The databases for evaluating CSR in China mainly includes the Blue Book on Corporate Social Responsibility of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Hexun.com, and Rankins. However, the sample of the blue book is very limited, with only 100 enterprises each year. Different from Rankins, which is more suitable for measuring the CSR disclosure quality, Hexun.com is more suitable for measuring the CSR performance (Zhong et al., 2019). The five indicators developed by the Hexun website according to stakeholders are subdivided into 13 secondary and 37 third-level indicators. For example, investor-oriented CSR consists of corporate governance, profitability, solvency, credit, and innovation; employee-oriented CSR consists of performance, safety, and caring for employees; supplier- and customer-related CSR includes product quality, after-sale service, integrity, and reciprocity; environment-oriented CSR includes environmental governance; and community-oriented CSR consists of contributing value. Moreover, the data sources of Hexun.com are very wide, including corporate information disclosure, corporate interviews and internal research, and web data crawlers. Hexun's data can comprehensively and objectively reflect CSR performance. In recent years, it has been widely used in relevant research in China, such as Xu and Ma (2021), and Zhang (2022), among others.

In particular, the existing anthropological and sociological literature on clans mainly focuses on rural areas with strong clan culture; however, most of the listed firms studied in this paper are registered in cities, which may create doubt about the credibility of the conclusion. In fact, China's large-scale urbanization process began only at the end of the previous century. Except for a few large cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, most cities developed based on rural areas. The shaping of individual cognition and behavior by culture can accompany these individuals throughout their entire lives and even through cross-generational inheritance (Liu, 2016). People born before the 1990s live in cities developed from rural areas. As the main participants in current market activities, these individuals’ values are deeply affected by clan culture. Guiso et al. (2006) proposed that cultural influence changes slowly. Although the urbanization process has brought about the improvement of material conditions, it cannot lead to the complete annihilation of the traditional cultural atmosphere. Clan culture is continued and inherited by the embedding of individual ideas and reproduction. Following a short period of urbanization, clan culture still exists in the Chinese mainland—in both its cities and the countryside.

The CGSS database (http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/index.htm) is the earliest national, comprehensive, and continuous academic survey project in China, and it was published by Renmin University of China. The database includes individual beliefs regarding society, government, and economy, and its data indicators can well reflect the impact of culture on individual value preferences.

This paper manually collects the per capita rice planting area of the chairmen's native places and enterprises’ registering places at the city level. The data comes from the demographic and natural statistics database of the China National Knowledge Infrastructure. Due to the few early statistical data, some cities with missing data are eliminated.