The objective of this paper is to investigate the potential of organisational design as a potent approach to supply chain risk management (SCRM). Using contingency theory, the current research distinguishes between two design options: organic and mechanistic organisations, both at the structural and cultural levels. The authors predict a positive relationship between the organic nature of structural and cultural elements and the level of supply chain risk mitigation. They also predict a positive interaction effect between structural and cultural elements. To test hypotheses, multiple and moderated regression analysis was conducted on a sample of 213 small and medium-sized enterprises in the Spanish agri-food supply chain. The results confirmed the proposed hypotheses. This research contributes to the literature on SCRM by opening a discussion on the impact of organisational design as means of managing supply chain risk. In particular, it draws attention to the positive combined effects of the different design characteristics (structural and cultural). Furthermore, this study provides managers with insights into the use of organisational design as an additional tool for managing supply chain risk.

As supply chains grow increasingly global and interconnected, companies encounter more diverse events that might disrupt their activity (Bilbao-Ubillos et al. 2024; Colicchia et al., 2010). As a result, supply chain risk management (SCRM) has drawn increasing attention in academia (e.g., Baryannis et al. 2019, Fan and Stevenson 2018, Ho et al. 2015, Wang et al. 2017, Wickasana et al. 2022). As recent literature reviews disclose (Fan and Stevenson, 2018; Ho et al., 2015; Wickasana et al., 2022), SCRM literature has identified a few relevant parameters of risk management (e.g., risk-causing events, risk assessment processes, risk mitigation strategies) and offered some explanations related to how they interact, with one another and with other business management parameters (e.g., Esmizadeh and Mellat Parast 2021, Pandey et al., 2023; Samson and Gloet, 2018) including organisational design.

Organisational design is well established as a tool for achieving desirable medium and long-term outcomes (e.g. Burns and Stalker 1961, Huang et al. 2010, Kessler et al. 2017, Lawrence and Lorch 1967, Mustafa et al., 2023; Thompson, 1967). Various variables such as firm size, technology or environment have been identified as determining the appropriate organisational design (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Child, 1972; Lawrence and Lorch, 1967; Thompson, 1967). For example, certain organisational designs are more appropriate in uncertain, hostile and risky environments (Mintzberg, 1979; Lawrence and Lorch, 1967), so that organisational design can act as a risk management tool, including in supply chain settings. As recent practitioner publications (e.g. Bailey et al. 2019) continue to discuss efficient ways of dealing with supply chain risk, disintangling a complex relationship between SCRM and organisational design will facilitate firms’ efforts in this regard.

There is no single, consensus definition of organisational design, but by reviewing both well-known and more recent contributions (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Cameron et al., 2022; Desphandé et al., 1993; Kessler et al., 2017; Mintzberg, 1979; Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1983), we propose that organisational design entails decisions regarding both structure and culture. Structure decisions determine how work will be divided in a company (e.g., specialised functions, multifunctional departments), as well as the practices through which it will be coordinated (e.g., vertical vs. horizontal communication, decision-making hierarchy, decision-making through mutual adjustment, decision-making through formalisation). Culture decisions instead refer to individual characteristics and values (Cameron et al., 2022; Kessler et al., 2017; Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1983; Reigle, 2001). Both these decisions likely have implications for risk management, so specifying the link between organisational design and SCRM could offer meaningful insights.

However, contributions related to the influence of organisational design on SCRM have been scarce (Nakano and Lau, 2020; Roh et al., 2017), often relegated to a side-line comment, beyond the main focus. With a few exceptions (e.g., González et al. 2020, González-Zapatero et al. 2021), these contributions also are conceptual, without empirical evidence to support their assertions. Many studies focus on a particular organisational design feature or practice (e.g., formalisation, appointing a risk manager, team composition), without acknowledging other features that also might be influential. For example, Lavastre et al. (2014) predict that greater formalisation in a company (e.g., implementation of ISO certificates) promotes the use of formalised SCRM programs, but they do not provide empirical evidence in support of this claim. González-Zapatero et al. (2021) provide empirical evidence of a counterproductive effect of the presence of risk managers on the efficacy of risk management; Manuj and Mentzer (2008) propose that employees’ culture might moderate the effects of different variables on the selection of a risk mitigation strategy. Therefore, these two studies are also limited to including an isolated organisational design parameter and Mentzer (2008) does not include empirical support for his proposal. In summary, while these contributions provide significant insights, a research gap persists. Accordingly, the motivation driving the current research effort is to establish a comprehensive view by integrating multiple structural and cultural organisational design elements and thereby provide theoretical and empirical evidence of their relationships with risk mitigation, as a specific SCRM parameter.

Decisions about structural and cultural elements of organisational design shape different types of organisations (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Mintzberg, 1979). For the purposes of this study, we will use Burns and Stalker's typology of organisations. These authors define companies as organic or mechanistic, represented as ends of a continuum (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Ju and Ning, 2023; Kessler et al., 2017; Mustafa et al., 2023). Burns and Stalker's (1961) framework has been widely applied in management studies to develop various models and theories, as well as adopted to explain other concepts, such as performance, innovation, satisfaction, ethics, leadership and learning (Chuang et al., 2012; Dust et al., 2014; Green and Cluley, 2014; Kessler et al., 2017; Martínez-León and Martínez-García, 2011; Pasricha et al., 2018; Patanakul et al., 2012). We prefer this organic–mechanistic typology, because it (1) constitutes a simple but well-accepted approach to basic organisational design that facilitates our attempt to understand its relationship with SCRM; (2) possesses intuitive characteristics, such that it may help introduce organisational design concepts to SCRM practitioners and readers with diverse backgrounds (e.g., engineering); and (3) can be broken down into structural and cultural characteristics, two components that likely have unique implications with regard to managing supply chain risk. In this sense, this research seeks to answer a specific and central question: Do organisations with more organic characteristics (structural and cultural) exhibit higher rates of supply chain risk mitigation?

To establish whether and how organisational design can influence the tactics a company uses to face and manage supply chain risk, we turn to contingency theory, which postulates that the appropriate organisational design depends on the contextual circumstances (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Kessler et al., 2017; Lawrence and Lorch, 1967; Mustafa et al., 2023; Thompson, 1967). According to this theory, organic organisations may be more suitable in changing and uncertain contexts (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Damanpour and Aravind, 2012; Desphandé et al., 1993; Wei et al., 2014). Analogously, the potential of organic organisations to react to threats in the environment and manage risks may be greater. Therefore, we propose a model marked by a positive relationship between organic organisations (structural and cultural levels) and the implementation of SCRM practices, in which an organic culture moderates the impact of organic structural characteristics on the extent of supply chain risk mitigation efforts.

This research contributes to the SCRM literature by initiating a discussion on how organisational design, including structure and culture, can support supply chain risk mitigation. This study also contributes to the organisational design literature, by highlighting how some design parameters can interact with others, namely how organisational culture moderates the effect of organisational structural characteristics on other variables.

In the next section, we review relevant literature, then present our conceptual model. After we explain the methodology, we report the empirical analysis and its results. Finally, we conclude with some implications for academia and practitioners.

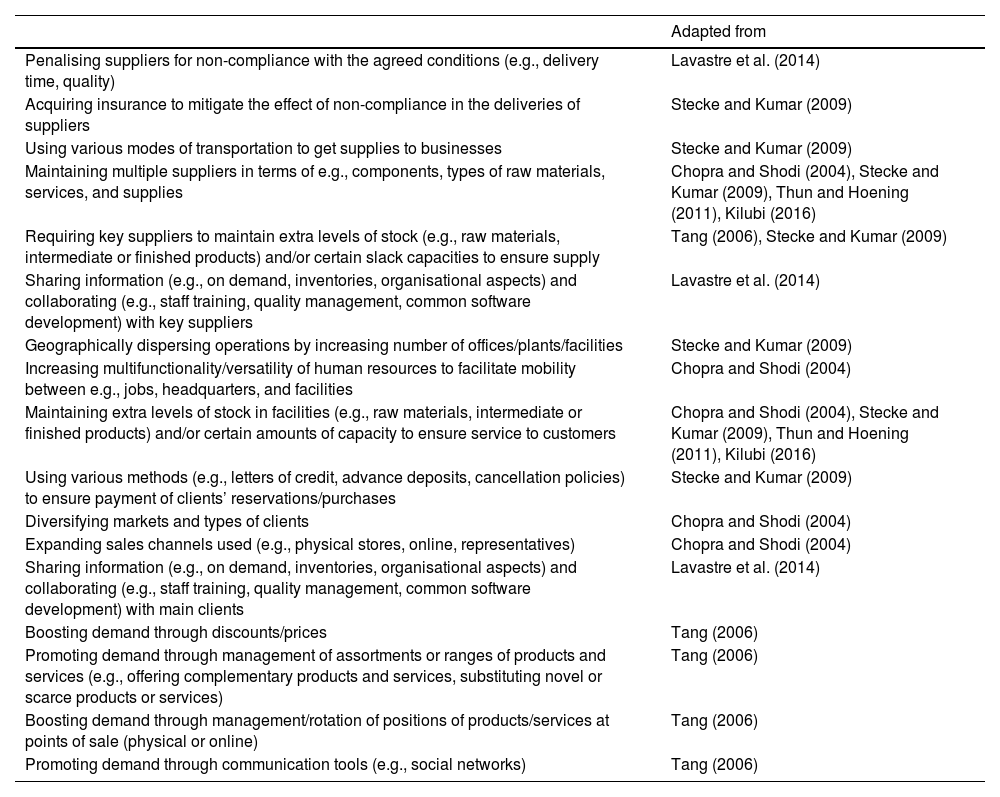

2Literature review2.1Supply chain risk managementSupply chain risk has been defined as the probability of events that might seriously damage the performance of a company's supply chain (e.g., Ho et al. 2015, Lavastre et al. 2014. Zsidisin and Ellram 2003). To deal with it, organisations must adopt a three-stage process: risk identification, risk assessment and implementation of risk mitigation strategies (Fan and Stevenson, 2018; Ho et al., 2015). First, to identify risk, the organisation reviews various events that may have adverse effects on the supply chain, classified according to whether they are internal or external (Ho et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2010; Trkman and McCormack, 2009; Wu et al., 2006). External events can be caused by human behaviours (e.g., war, terrorism, political instability, adverse regulation) or acts of nature (e.g., pandemics, earthquakes, floods). Internal events can be caused by companies themselves or by their partners in the supply chain (e.g., poor planning, poor management, opportunism). Second, regarding the assessment of risk, most authors refer precisely to the probability and severity parameters in previously provided definitions of risk (Baryannis et al., 2019; Hallikas et al., 2004; Harland et al., 2003; Knemeyer et al., 2009; Norrman and Jansson, 2004; Tummala and Schoenherr, 2011). Third, risk mitigation implies the implementation of various practices (Chopra and Sodhi, 2004; Ho et al., 2015; Kilubi, 2016; Mishra et al., 2016; Stecke and Kumar, 2009; Tang, 2006; Thun and Hoenig, 2011; Zsidisin and Ellram, 2003), such as deferring risk to supply chain partners through fines, rewards, or insurance. Another option is to diversify risk by duplicating suppliers and facilities or diversifying markets. Still others use “buffering” (Tang, 2006), to focus on accumulating stock at strategic points in the supply chain, or “bridging” (Mishra et al., 2016), to collaborate with partners in the supply chain through practices such as postponement. Finally, some companies try to stimulate supply chain demand (Tang, 2006). We compile some of the most commonly mentioned risk mitigation strategies in prior literature, including practices to mitigate risk upstream in the supply chain, risk within companies themselves, and risk downstream of the supply chain, in Table 1, with citations to previous conceptual and empirical studies of them.

Supply chain risk mitigation strategies.

| Adapted from | |

|---|---|

| Penalising suppliers for non-compliance with the agreed conditions (e.g., delivery time, quality) | Lavastre et al. (2014) |

| Acquiring insurance to mitigate the effect of non-compliance in the deliveries of suppliers | Stecke and Kumar (2009) |

| Using various modes of transportation to get supplies to businesses | Stecke and Kumar (2009) |

| Maintaining multiple suppliers in terms of e.g., components, types of raw materials, services, and supplies | Chopra and Shodi (2004), Stecke and Kumar (2009), Thun and Hoening (2011), Kilubi (2016) |

| Requiring key suppliers to maintain extra levels of stock (e.g., raw materials, intermediate or finished products) and/or certain slack capacities to ensure supply | Tang (2006), Stecke and Kumar (2009) |

| Sharing information (e.g., on demand, inventories, organisational aspects) and collaborating (e.g., staff training, quality management, common software development) with key suppliers | Lavastre et al. (2014) |

| Geographically dispersing operations by increasing number of offices/plants/facilities | Stecke and Kumar (2009) |

| Increasing multifunctionality/versatility of human resources to facilitate mobility between e.g., jobs, headquarters, and facilities | Chopra and Shodi (2004) |

| Maintaining extra levels of stock in facilities (e.g., raw materials, intermediate or finished products) and/or certain amounts of capacity to ensure service to customers | Chopra and Shodi (2004), Stecke and Kumar (2009), Thun and Hoening (2011), Kilubi (2016) |

| Using various methods (e.g., letters of credit, advance deposits, cancellation policies) to ensure payment of clients’ reservations/purchases | Stecke and Kumar (2009) |

| Diversifying markets and types of clients | Chopra and Shodi (2004) |

| Expanding sales channels used (e.g., physical stores, online, representatives) | Chopra and Shodi (2004) |

| Sharing information (e.g., on demand, inventories, organisational aspects) and collaborating (e.g., staff training, quality management, common software development) with main clients | Lavastre et al. (2014) |

| Boosting demand through discounts/prices | Tang (2006) |

| Promoting demand through management of assortments or ranges of products and services (e.g., offering complementary products and services, substituting novel or scarce products or services) | Tang (2006) |

| Boosting demand through management/rotation of positions of products/services at points of sale (physical or online) | Tang (2006) |

| Promoting demand through communication tools (e.g., social networks) | Tang (2006) |

Contingency theory suggests there is no “best option” to design an organisation. The appropriateness of an organisational design depends on variables such as the environment (Lawrence and Lorch, 1967), degree of uncertainty (Thompson, 1967), production technologies (Woodward, 1958) and the degree of change faced by an organisation (Burns and Stalker, 1961). Contingency theory offers a counterpoint to positivist approaches, which seek scientifically universal principles to optimise productivity (Boyd et al., 2012; Kessler et al., 2017). Within this framework, Burns and Stalker (1961) propose a distinction between mechanistic and organic organisations, according to organisational design elements that have since been diversely defined, synthesised and classified (Cruz and Camps, 2003; Kessler et al., 2017). For the purposes of this study, we synthesised these elements using two criteria, similar to those applied in prior research. First, the selected element should reflect the main ideas of Burns and Stalker's work, as reviewed by Kessler et al. (2017). Second, they should be the most frequently cited elements across various proposals (e.g., Cruz and Camps 2003, Huang et al. 2010, Kessler et al. 2017, Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983, Sine et al. 2006, Wei et al. 2014).

2.2.1Structural elements of organic organisationsSome elements—labelled ‘structural elements’, such as the degree of specialisation, job formalisation, decision-making centralisation, chain of command, or communication channels used in organisations—help establish the mechanistic–organic character of organisations, because they are objective and unrelated (Kessler et al., 2017). However, the terminology used to refer to structural elements is not uniform; literature reviews on the topic show wide variation (Cruz and Camps, 2003; Kessler et al., 2017). Using the previous definition of the organisational design decision as it pertains to structure, we consider one structural element to explain how labour gets divided into organic structures, then refer to two additional structural elements to explain how the labour of entire groups can be coordinated through internal integration, which requires communication and decision-aligning practices.

The first structural element that defines an organic structure is a low degree of specialisation. In mechanistic organisations, common concerns get broken down into specialised functional tasks, whereas in organic organisations, there is less specialisation and greater concern for general organisation tasks (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Kessler et al., 2017). Mechanistic organisations are function-oriented, whereas organic organisations are product-/market-oriented (Cruz and Camps, 2003).

The second structural element that defines an organic structure is lateral communication. In mechanistic organisations, communication is vertical, and interaction tends to occur between subordinates and superiors. In organic organisations, communication tends to be lateral (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Kessler et al., 2017). Consequently, in mechanistic organisations, knowledge is located at the top of the hierarchy, whereas in organic ones, it can be located anywhere in the organisation (Burns and Stalker, 1961).

The third structural element that characterises organic structures is horizontal decision-making. Once the work of a group is divided among its members, decisions must be made to coordinate this work. Mintzberg (1979) proposes three ways to coordinate decision-making in organisations: (1) through direct supervision by a manager in the next upper level of hierarchy; (2) through formalisation of processes, goals or skills; or (3) through mutual adjustment. Although direct supervision can coordinate the work of simple and small organisations, it becomes slower and less suited to changing conditions as organisations get bigger. When the work is repetitive, the formalisation of the process with rules acts as a coordination mechanism. As the work becomes more unpredictable however, so do processes; their formalisation grows impossible. Only goals can be formalised, allowing employees to find the best way of achieving them. When even goals cannot be formalised because of uncertainty, organisations can formalise the skills that employee's need to achieve the best possible decisions. Mintzberg (1979) uses the example of the skills of surgeons as a mechanism to find the best coordinated solutions, concluding that because direct supervision or hierarchy and formalisation of processes are less suited to coordinating decision-making in rapidly changing conditions, they are not organic decision-coordination mechanisms. Instead, mutual adjustment guided by formalisation of goals or skills is a more organic decision-coordination mechanism. This explanation is coherent with Burns and Stalker's (1961) description of organic organisations, which indicates that mechanistic organisations are characterised by hierarchical structures of control and authority, whereas organic organisations are characterised by network structures of control and authority (Kessler et al., 2017). For this study, we refer to this third characteristic as horizontal decision-making.

2.2.2Cultural elements of organic organisationsSeveral authors highlight employee characteristics, such as values (e.g., commitment, responsibility), knowledge or skills (e.g., cosmopolitanism, varied skills, leadership), as necessary complements to structural elements in organic organisation designs (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Cruz and Camps, 2003; Deshpandé et al., 1993; Kessler et al., 2017; Mintzberg, 1979; Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1983). Employee characteristics also have been used to define organic cultures. Therefore, we refer to employee characteristics as cultural elements of organic organisations.

The first cultural element that characterises organic structures is employees’ broad commitment. In mechanistic organisations, employees’ commitment is limited to the specialised tasks for which they are responsible. In organic organisations, employees focus their commitments and responsibilities on the company as a whole. Employees of organic organisations avoid positioning problems as someone else's responsibility (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Kessler et al., 2017); they understand their predefined tasks can be redefined on the go.

The second cultural element that characterises an organic organisation is employees’ broad knowledge. In mechanistic organisations, importance and prestige are associated with internal, local knowledge, whereas in organic organisations, they are associated with general, cosmopolitan, and external knowledge (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Kessler et al., 2017). External general knowledge is less specific and therefore more varied; according to Mintzberg (1979), workers’ broad preparation allows them to coordinate decisions. As we subsequently explain, organic organisations apply horizontal decision-making, for which broad, cosmopolitan preparation is a necessary complement. Moreover, other scholars identify broad knowledge as a characteristic of organic organisations (Kessler et al., 2017).

The third cultural element associated with organic structures is employees’ proactivity. Entrepreneurship, flexibility, anticipation, proactivity and innovation also represent important values in organic organisations (Deshpandé et al., 1993). Although we rely mainly on the mechanistic–organic framework based in contingency theory, we integrate this third component from the competing values framework (Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1983). As we detail further when we present our conceptual model, this component can be essential to manage risk. Table 2 lists the characteristics of organic organisations.

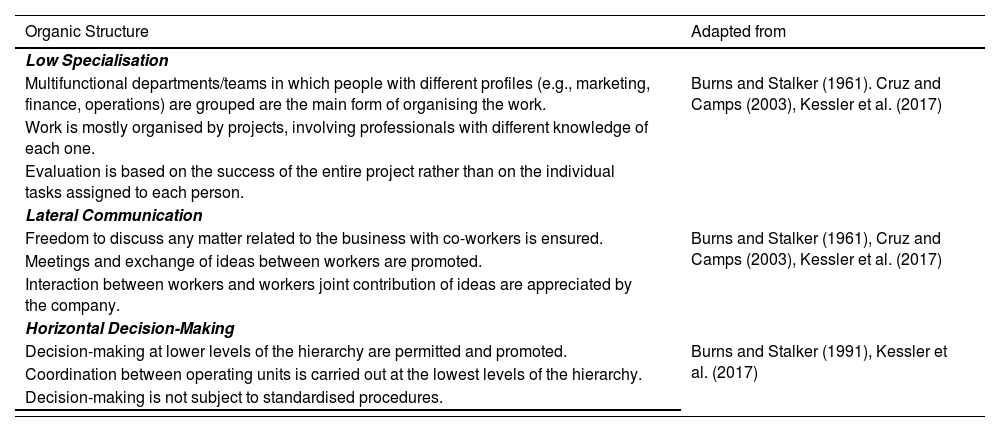

Characteristics of organic organisations.

| Organic Structure | Adapted from |

|---|---|

| Low Specialisation | |

| Multifunctional departments/teams in which people with different profiles (e.g., marketing, finance, operations) are grouped are the main form of organising the work. | Burns and Stalker (1961). Cruz and Camps (2003), Kessler et al. (2017) |

| Work is mostly organised by projects, involving professionals with different knowledge of each one. | |

| Evaluation is based on the success of the entire project rather than on the individual tasks assigned to each person. | |

| Lateral Communication | |

| Freedom to discuss any matter related to the business with co-workers is ensured. | Burns and Stalker (1961), Cruz and Camps (2003), Kessler et al. (2017) |

| Meetings and exchange of ideas between workers are promoted. | |

| Interaction between workers and workers joint contribution of ideas are appreciated by the company. | |

| Horizontal Decision-Making | |

| Decision-making at lower levels of the hierarchy are permitted and promoted. | Burns and Stalker (1991), Kessler et al. (2017) |

| Coordination between operating units is carried out at the lowest levels of the hierarchy. | |

| Decision-making is not subject to standardised procedures. |

| Organic culture | Adapted from |

|---|---|

| Broad Commitment | |

| Workers are highly committed to the success of the business (beyond the commitment to the specific tasks for which they are responsible). | Burns and Stalker (1961), Deshpandé et al. (1993), Kessler et al. (2017) |

| Workers feel responsible for solving any problem in their company, not just those directly related to their job positions. | |

| Management strives for workers to understand the general dynamics of the market and its main problems, | |

| Broad Knowledge | |

| The company strives to train workers in transversal knowledge and skills (valid in most companies). | Burns and Stalker (1961), Kessler et al. (2017), |

| The company trains workers to be able to perform a wide range of tasks. | |

| The company prioritises the selection of personnel with extensive and varied training. | |

| Proactivity | |

| The company places special emphasis on hiring personnel with a proactive and flexible profile that seeks new resources and solutions. | Deshpandé et al. (1993)Cameron and Quinn (2011) |

| The company places special emphasis on training workers to encourage their proactivity and capacity for innovation. | |

| The company especially values the proactive leadership of the workers. |

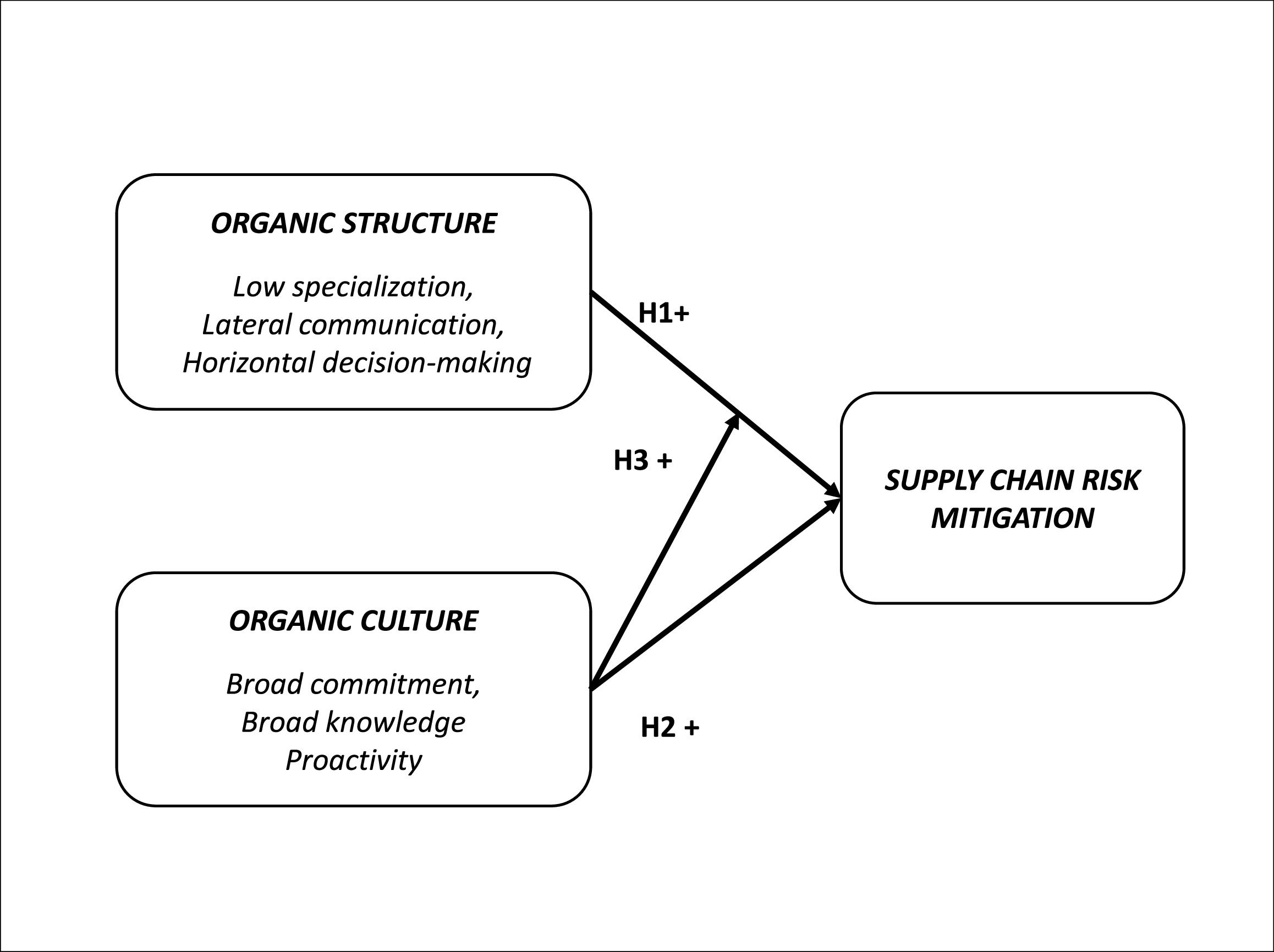

Fig. 1 illustrates our conceptual model. Organisations that rely intensively on organic characteristics, in terms of both structure and culture, are more flexible and more capable of adapting to market opportunities and threats (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Damanpour and Aravind, 2012; Desphandé et al., 1993; Wei et al., 2014). This type of organisation also is more well-suited to innovating (Damanpour and Aravind, 2012; Kessler et al., 2017). Risk management, as previously explained in Section 2.1, also consists of identifying threats in the market or environment, assessing those threats and reacting to them by implementing various risk-mitigation strategies (Fan and Stevenson, 2018; Ho et al., 2015). According to this analogy, we propose the following relationships.

Organisations that have high degrees of specialisation and little lateral communication are less able to identify risks that may affect their supply chain performance; their employees’ degree of specialisation makes them myopic about the risks that affect units outside their areas of expertise (Schoenherr and Swink, 2012; Swink and Schoenherr, 2015). For example, a company might have separate, highly specialised marketing and purchasing departments with little intercommunication: One department handles upstream supply chain transactions, and the other department handles downstream supply transactions. If sales of a particular product suddenly increase, the purchasing department may not notice the increase fast enough to apply upstream supply chain mitigation strategies to guarantee the supplies needed to manufacture the product (e.g., ask suppliers to keep extra stock of the required components). Similarly, supply of a particular product may run short, and the marketing department may be slow to realise it should promote other items instead. In contrast, if a company has a lower degree of specialisation and/or a greater degree of intercommunication, it will more easily detect this type of risk associated with supply chain performance. Risk management requires risk identification and communication (‘risk transparency’) throughout organisations (Lam, 2014).

However, risk mitigation in the supply chain goes beyond the mere identification of risks; companies must evaluate risks and make decisions about risk mitigation strategies. In companies in which decisions are made at the highest levels, risk mitigation decisions might be made slowly (Mintzberg, 1979) or not at all, because if they are not carried out quickly, there may be no reason to apply them. Similarly, companies in which decisions are made through highly formalised procedures may be slow or unable to react to new situations. Organisations in which decisions that affect different parts of the supply chain (i.e., suppliers, clients, companies themselves) are aligned through coordination at lower levels of the hierarchy can react in a timely manner (González-Zapatero et al., 2017). According to these premises, we hypothesise:

H1 The more organic a company's structure, the higher its level of risk mitigation.

However, our model postulates that it is not only the structural characteristics of organisations that promote risk mitigation but also the characteristics associated with employees and cultures. Workers who are committed to the business, rather than merely to the tasks for which they are responsible, are more likely to detect problems that affect the entire supply chain and more likely to seek solutions (Foote et al., 2005; Ismail et al., 2012). For example, if purchasing department employees who are very committed to their company detect that a component cannot be supplied, it is likely that they will not only try to solve the supply problem but also informally inform other members of the company about it, to reduce the risks arising from the shortage; they might try to persuade their marketing partners not to promote products associated with the missing components or raw materials. Extensive training of workers also can function as an informal risk-detection/solution-finding mechanism; those who have broad and varied training will be less myopic and better able to detect problems throughout the supply chain. Employees’ proactivity is decisive in promoting the implementation of risk mitigation strategies, in both their own departments and others. Proactive workers are employees who seek to detect opportunities or threats and create favourable conditions (Crant, 2000; Sax and Torp, 2015). According to these premises, we hypothesise:

H2 The more organic a company's culture, the higher its level of risk mitigation.

Finally, the majority of the existing literature suggests a positive relationship between structural and cultural elements of organisational design (Dickson et al., 2006; Kessler et al., 2017; Reigle, 2001). However, some studies also suggest a moderating relationship. For example, Reigle (2001) indicates that organic organisations are more likely to retain highly skilled knowledge workers, who require access to the features of organic structures (e.g., freedom to communicate with other departments, distributed decision-making) to reach their full potential. Analogously, highly committed and proactive workers with broad business knowledge might need organic organisations to achieve their potential. Efforts to leverage the structural elements of organisational design in risk mitigation also might benefit from cultural elements. If a company promotes organic structural features (e.g., horizontal communication and decision-making) but employs workers who are relatively less committed to its performance or less proactive, these employees might not promote the implementation of the risk mitigation strategies. As another example, a company might promote organic structural features but hire employees with narrow, rather than broad, training, whose myopic perspectives prevent them from taking full advantage of lateral communication to identify risks. Overall then, to benefit from an organic organisational design in their supply chain risk mitigation efforts, companies may require a fit between their organic structure and culture (Boyd et al., 2012). A lack of fit instead might lead to poorer SCRM performance (Manuj and Mentzer, 2008). Therefore, we hypothesise:

H3 Organic culture positively moderates the positive effect of organic structure on supply chain risk mitigation levels.

Before introducing our methodology, we clarify that with our model, we anticipate that the organic features of an organisation (structural and cultural) have positive impacts on the level of supply chain risk mitigation in general. These features promote risk identification and assessment, and those two stages encourage risk mitigation in various areas of the supply chain (Braunscheidel and Suresh, 2009; Kern et al., 2012). We have no theoretical reason to anticipate that organic features or the interaction of organic culture and organic structure would exert different impacts on the level of risk mitigation across different elements of the supply chain (e.g., upstream, downstream, internal). Therefore, we analyse the impact on supply chain risk mitigation in aggregate.

4Methodology4.1DataTo test our model, we selected a population of 1422 Spanish small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) from the Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System database (SABI). The database contains the financial information of more than 2.6 million companies in Spain and Portugal. The study population included 530 SMEs that belonged to the agri-food sector and 892 SMEs that belonged to the hotel and restaurant sector, both of which are part of the Spanish agro-food supply chain. The SME definition we applied for the data collection specifies an enterprise with fewer than 250 employees, turnover of less than 50 million euros or a balance sheet total of less than 43 million euros (European Commission, 2003). The study population thus included companies with between 50 and 250 employees.

The agri-food supply chain provides an ideal context for investigating the proposed relationships for several reasons. First, we expect supply chain risk mitigation to be present in this agri-food supply chain, considering its high levels of risk exposure, due to unpredictability and increased costs (Ahumada and Villalobos, 2009; Xu and Gursoy, 2015). The agri-food upstream supply chains are characterised by long lead times and high levels of uncertainty in material supply, such as weather-related fluctuations in crop yields (Ahumada and Villalobos, 2009). Similarly, firms in the downstream agri-food supply chains are subject to high levels of demand uncertainty, mainly due to seasonal variations in demand for products and services (Ahumada and Villalobos, 2009), as well as the high perishability of the goods (Lowe and Preckel, 2004). During our data collection, which occurred in the first half of 2021, the downstream agri-food supply chain (hospitality) also experienced a drop in demand due to COVID-19 mobility restrictions (Rios Rodriguez et al., 2023; Vayá et al., 2023). Second, we expect variability in the level of mitigation strategies implemented, because some companies (i.e., hospitality) experienced stronger negative impacts in 2020 due to COVID-19 than others (i.e., agri-food) (Informa DBK, 2020). Such variability supports our efforts to test the proposed hypotheses. Third, we expect organic characteristics to be present in these small firms (Mintzberg, 1979); a substantial percentage of SMEs also are family firms, whose employees tend to exhibit strong organisational commitment, similar to the organic cultural element we investigate (Christensen-Salem et al., 2021; Gomez-Mejía et al., 2007; Mowday et al., 1979; Pimentel et al., 2020). Fourth, organic characteristics are contingent on factors such as size and technology, such that we reasonably expect some variation in the organic characteristics of our sample, which also support our hypotheses tests. In detail, in our sample, firm size varies from 50 to 250 employees, and the technology varies from agri-food to hospitality.

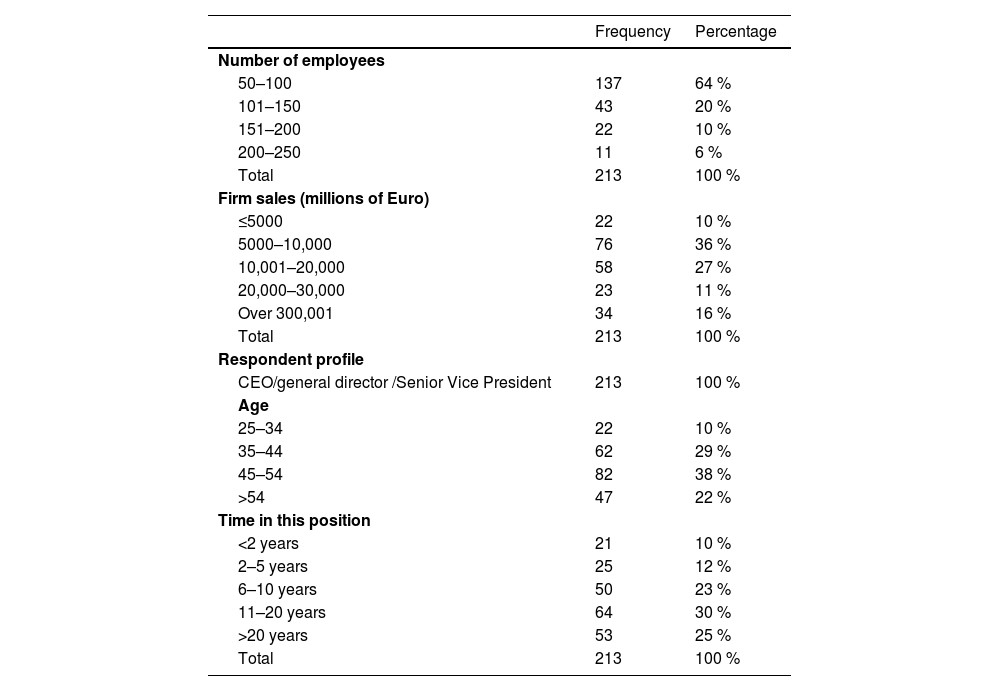

We sent an online survey with questions related to the model variables to the general managers of these companies. We created the survey by using Qualtrics Software and followed Dillman's (2000) methodology to increase the response rate. The questionnaire was pre-tested by two academics, two purchasing managers and four general managers to guarantee its clarity and readability. Then, to increase response rates, we undertook several steps. First, we made direct telephone calls to company managers to present the study directly to the managers or at least to one of their assistants. Second, we sent emails to each manager, which included links to our online Qualtrics questionnaire. Third, we followed up with two more rounds of telephone and email reminders. Accordingly, we obtained 213 complete responses: 106 from the agri-food sector and 107 from the hospitality sector. The overall population response rate was 15 %. Table 3 lists the sample distribution in terms of number of employees, firm sales and respondent profiles (age and length of time in position).

Sample distribution.

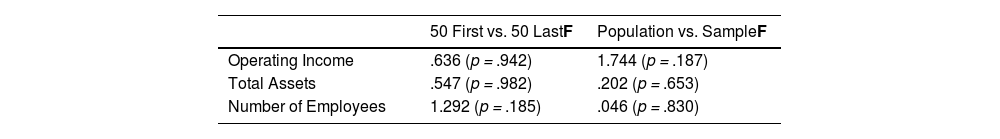

To check for non-response bias, we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) on demographic variables that could exert influences on our dependent variables. We found no significant differences between the sample and the population, nor between the first 50 and last 50 responses (Wagner and Kemmerling, 2010), as Table 4 shows. We obtained demographic characteristics from the SABI database. To reduce the risk of common method bias when designing the questionnaire, we followed Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) recommendations, such that questions related to the dependent variable appeared first in the questionnaire, and each section of the questionnaire was clearly visually separated from the rest. We conducted a Harman test to ensure that common method bias was not a problem (Podsakoff et al., 2003); it revealed that the items loaded not on a single factor but rather on 12 different factors, accounting for 70 % of the variance.

4.2Scale measurement4.2.1Dependent variable: supply chain risk mitigationWe measured supply chain risk mitigation using a multi-item, Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (‘very low’) to 7 (‘very high’), on which respondents rated the degree to which various risk mitigation strategies (Table 1) had been implemented in their companies. These mitigation strategies are not complementary; a company that chooses to implement some of them does not have to implement all of them. For example, a company may ask its suppliers to maintain a certain stock of supplies but choose not to duplicate suppliers, or vice versa. Each strategy implies a different way of dealing with risk in the supply chain. The selected group of mitigation strategies a company ultimately implements depends on different variables, such as the level of risk in each area of the supply chain or the cost–benefit trade-off of a given mitigation strategy. As Pettit et al. (2019) recognise, implementing mitigation strategies is costly. Yet the more risk mitigation strategies a company implements, the higher the level of supply chain risk mitigation it likely achieves. Because this scale meets the characteristics of a formative measure (Jarvis et al., 2003), we used the average of the respondents’ ratings of the implementation of strategies included in Table 1 to measure this variable.

4.2.2Independent variables: organic structure and organic cultureTo measure the organic character of the organisation, we asked respondents to rate, on a scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 7 (‘completely’), the extent to which various statements described the reality of their company. These statements referred to various structural and cultural elements of the organic organisations, as described in Section 2.2. There is no universally accepted measure of an organic organisation (e.g., Cruz and Camps, 2003, Huang et al. 2010, Wei et al., 2014). Therefore, to obtain a comprehensive scale that encompasses the main elements of organic organisations, we adapted items from both previous research (Cruz and Camps, 2003) and theoretical contributions (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Cameron and Quinn, 2011; Deshpandé et al., 1993; Kessler et al., 2017).

As for risk mitigation, companies may choose to adjust to some characteristics of organic organisations but not others; for example, at the structural level, both delegation of decision-making and strengthening of communication mechanisms are characteristics of organic companies. However, some companies may promote only one of these features. Similarly, at the cultural level, employee commitment and proactivity are characteristics of organic companies (Kessler et al., 2017), but employees might be only committed or only proactive, rather than both. However, the more organic characteristics a company presents, at both levels, the more organic its organisation. Therefore, to measure these two constructs, we calculated the arithmetic means of (1) structural organic characteristics of the organisation and (2) organic characteristics of the organisation's employee culture.

Control variables

A company's implementation of supply chain risk mitigation strategies also might be influenced by factors other than the independent variables we include in the model. For example, ISO 9001–certified companies tend to be larger than those that are not certified (Lo and Chang, 2007; Mokhtar and Muda, 2012). Because the most recent version of ISO 9001 includes risk analysis, we posit that larger companies may be more likely to analyse and mitigate risk, as well as to have the resources to pay for risk analysis external services. Taking these arguments into account, we include company size as a control variable, measured as company operating income and number of employees, obtained from the SABI database.

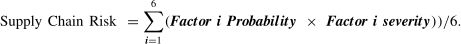

The level of supply chain risk mitigation adopted by a firm also might increase with the level of risk within the supply chain, a type of risk referred to as internal supply chain risk (Wu et al., 2006), micro risk (Ho et al., 2015) or endogenous uncertainty (Trkman and McCormack, 2009). Without any commonly used measure of this form of supply chain risk, we draw on previous literature to develop our scale. We asked respondents to grade the probability, on a scale from 1 (‘very low’) to 7 (‘very high’), of different factors occurring in the supply chain and how severe the consequences would be for their companies. The six factors are: (1) number of clients decreases or clients’ negotiating power increases, (2) alternative number of suppliers decreases or dependency on current supplier's increases, (3) pressure from competitor's increases, (4) new products/services emerge that replace or compete with company's products/services, (5) new competitors emerge in company's sector and (6) company's human resources (knowledge, skills, abilities) become obsolete. Although all six factors have been cited in previous work that seeks to define supply chain risk (Ho et al., 2015; Trkman and McCormack, 2009; Wu et al., 2006), there is no common terminology for them. Because the factors can be identified easily using Porter's (1997) well-known five forces, we decided to use wording inspired by this work. Then, in line with prior literature (Baryannis et al., 2019; Hallikas et al., 2004; Harland et al., 2003; Knemeyer et al., 2009; Norrman and Jansson, 2004; Tummala and Schoenherr, 2011), we computed the potential risk of each factor as the product of probability and severity, then generated the scale according to the following formula:

Finally, extent to which a company implements risk mitigation might be determined by its sector; different sectors generally exhibit different supply chain mitigation common practices. Therefore, we include the company sector (obtained from the SABI database) as a control variable.

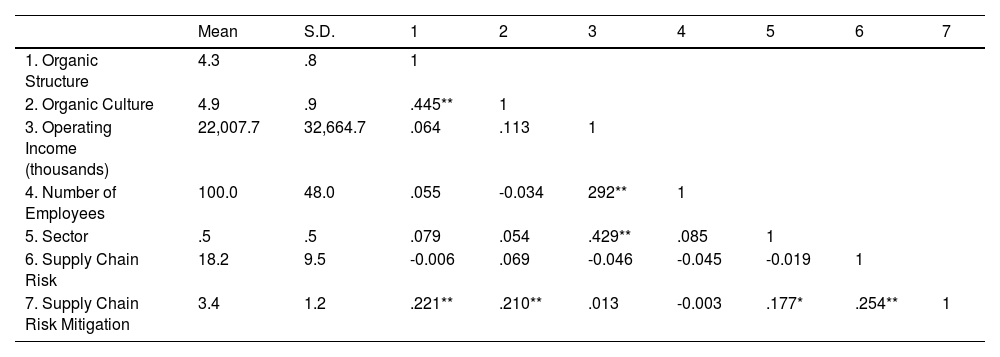

4.3AnalysisTo test our proposed model, we applied moderated multiple regression (MMR), which requires estimating a series of linear regression models (Hair et al., 2019). Table 5 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables. Because the two independent variables in our model indicate significant correlations, in an attempt to avoid misinterpretation derived from collinearity, we estimated five models, using a common procedure to test for the moderation (Sharma et al., 1981). The first model incorporates only the control variables as predictors. Each independent variable was added separately in the second and third models. The fourth model incorporates both variables together, and the fifth model includes the interaction term formed by the multiplication of the independent variable and the moderator. In the fifth model, only the coefficient of the interaction terms should be interpreted, because the coefficients of the independent variable do not offer the same meaning as in the other models.

Correlations.

Note: S.D: Standard deviation.

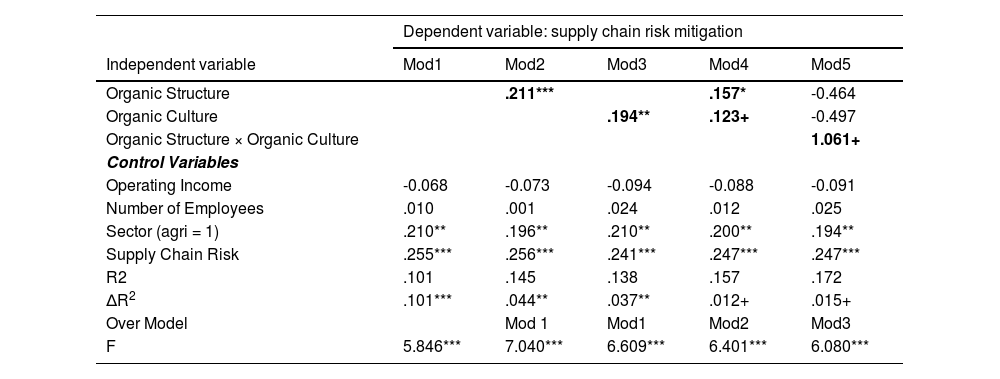

Table 6 shows the outcomes of the five estimated models. Regarding the control variables, Model 1 reveals that the agri-food sector is more proactive in mitigating risk in supply chains than is the hospitality sector, probably because it depends more on specific supplies, and clients can move relatively easily to other suppliers. Model 1 also shows that, as expected, the level of supply chain risk has a positive, significant effect on supply chain risk mitigation (β = 0.255, p < .001). When the level of supply chain risk is higher, it is logical to expect greater risk mitigation effort. These findings are consistent with the existing literature (Lavastre et al., 2014). However, the results do not indicate a relationship between company size (whether measured as operating outcome or number of employees) and risk mitigation. Although the firms in our sample vary in size, perhaps the size difference is not enough to prompt distinct risk mitigation levels. That is, larger companies likely have more developed SCRM systems, which implies a higher level of risk mitigation (Lo and Chang, 2007; Mokhtar and Muda, 2012). Yet all the companies in our sample are SMEs (50–250 employees), such that they might not have reached a sufficient size to have established a strongly developed SCRM system. In addition, SMEs are expected to have a lower level of implementation of risk mitigation strategies due to their low resource endowment and lack of supply chain management related skills (Adian et al., 2020; Tsilika et al., 2020; Son et al., 2019, 2021).

Effect of organic organisations on supply chain risk mitigation.

+p < .1, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Model 2 reveals a significant positive effect of organic structure on supply chain risk mitigation (β = 0.211, p < .001), which confirms H1. Risk mitigation represents the logical final step of risk management (Fan and Stevenson, 2018), after the identification and assessment of different sources of risk. As expected, our results confirm that organisations with more organic structures facilitate all these steps, such as risk identification through lateral communication and risk assessment and mitigation through horizontal decision-making. Lateral communication enables employees managing the downstream supply chain (i.e., sales) to exchange views with employees managing the upstream supply chain (i.e., buyers), facilitating their ability to identify mismatches, such as supply shortages or demand decreases, and respond (González-Zapatero et al., 2017) with different mitigation strategies (e.g., duplicating suppliers, finding new commercialisation channels).

Model 3 indicates a significant positive effect of organic culture on supply chain risk mitigation (β = 0.194, p < .01), which confirms H2. Employee characteristics thus have their own potential for promoting supply chain risk mitigation. Broad employee knowledge facilitates the identification of risks and suggestions of risk mitigation alternatives; employees’ commitment and proactivity also promote the implementation of risk mitigation strategies (Foote et al., 2005; Ismail et al., 2012).

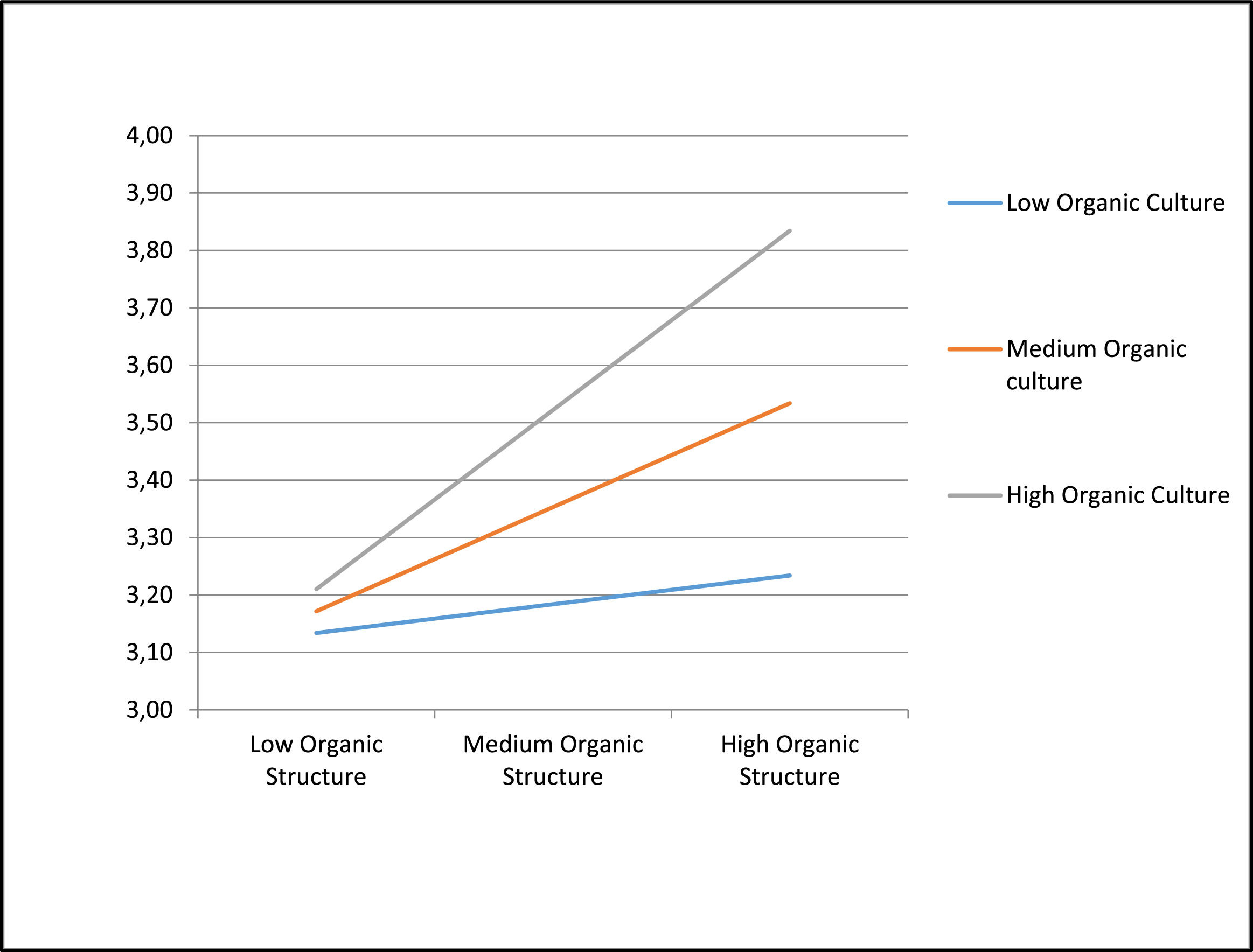

According to Model 4, the effects of both types of organic characteristics (structural and cultural) remain significant when we include both simultaneously in the regression. Thus, both elements can help explain the level of risk mitigation achieved. Model 5 shows that organic culture positively moderates the effect of organic structure on supply chain risk mitigation (β = 1.061, p < .1), which confirms H3. As expected, the cultural element, which reflects employee characteristics such as commitment to the company or proactivity, fosters the structural elements. Some previous literature predicts that skilled workers need a well-aligned organisational design to perform at their peak (Reigle, 2001), and our results confirm that aligning the organic structure and culture also is an effective tool for increasing the level of supply chain risk mitigation.

Fig. 2 presents the interaction plot for these three variables, revealing the relationships among them in greater detail. It depicts the interaction between organic structure and supply chain risk mitigation in three different situations: when the level of organic culture is low, when it is medium and when it is high. The positive slope of the relationship between organic structure and supply chain risk mitigation steepens when the level of organic culture is higher. These results confirm that organic structure is enhanced by employees’ profiles; when employees are more committed to their employers’ businesses, have broader knowledge and are more proactive, they take advantage of organic structures to protect their companies by practicing mitigation.

6ConclusionSupply chain risk management (SCRM) research has increased notably in recent decades. Today's globally extended supply chains are more exposed than ever to risks of all kinds (e.g., natural disasters, diseases, political tensions, economic crises, technological disruptions, unexpected changes in client preferences, competitors’ actions, supplier availability) (Fan and Stevenson, 2018; Ho et al., 2015; Stecke and Kumar, 2009). Prior SCRM literature has sought to determine which practices better manage risk (Fan and Stevenson, 2018; Ho et al., 2015; Nakano and Lau, 2020; Wickasana et al., 2022). Among these practices, a few articles mention different organisational design decisions (Gonzalez-Zapatero et al., 2021; Lavastre et al., 2014; Manuj and Mentzer, 2008), but these contributions remain mainly at the theoretical level and are not well-developed. However, a large body of literature contrasts organic organisations with mechanistic organisations, postulating that organic organisations can more effectively manage dynamic, changing situations. Reflecting that literature stream, as well as the reality that risk accompanies change, we propose a model that explains why organic organisations are more proactive in mitigating supply chain risk. Our results confirm the logic of this model.

6.1Theoretical contributionsPrevious SCRM research has sought to identify strategies that help organisations deal with risk. As explained in Section 2.1, this list of strategies is long and includes different approaches to risk mitigation (e.g., risk spread, risk diversification, collaboration, buffering). Some studies suggest that organisational design also can be a tool for dealing with risk (González-Zapatero et al., 2021; Lavastre et al., 2014; Manuj and Mentzer, 2008). However, such studies are scarce, focused on isolated elements of organisational design and often conceptual.

By providing evidence of the relationship between organisational design and risk management, our results invite academics to identify which organisational structure is better at dealing with risk. For example, is it better to appoint a risk manager who bears all responsibility for risk management, or is it better to involve all workers in dealing with risks? Some authors find that having risk managers can be counterproductive to risk management efficacy (González et al., 2020; González-Zapatero et al., 2021) or financial performance Otero González et al. (2020), and Lavastre et al. (2014) recommend process formalisation as a mechanism to deal with risk. However, our results suggest that horizontal mutual coordination enhances supply chain risk mitigation. If formalisation and mutual adjustment are alternative coordination systems (Mintzberg, 1979), should risk management be a formalised procedure or rely more on mutual adjustment practices?

Thus, the first theoretical contribution of this paper is to initiate an important debate on the impact of organisational design decisions on the way companies manage supply chain risks.

The second contribution is that this research sheds light on the role of organisational culture in effective SCRM, which has been a relatively underexplored area in SCRM research. Indeed, our results also draw attention to firm culture, and especially to employees’ characteristics, as effective tools for dealing with risk. Kessler et al. (2017) highlight that organic organisations are defined not only by structural characteristics but also by employee characteristics, which we refer to as organisational culture. The employee component of organic organisations often has been neglected by researchers. With only rare exceptions (San-Jose et al., 2022), literature has not considered the relationship of this component with risk management. However, because our results reveal that ethics, skills and education affect risk management, scholars should take this relationship into account when designing further studies.

The third theoretical contribution of this study is that we have answered the previous call that more research is needed to better understand the role of internal integration as an important antecedent of SCRM (Braunscheidel and Suresh, 2009; Duhamel et al., 2016; Jajja et al., 2018; Munir et al., 2020; Narashiman and Talluri, 2009; Riley et al., 2016; Wicaksana et al., 2022). However, internal integration may be achieved through different organisational design decisions (i.e., horizontal vs. vertical communication). Prior literature has not specified which organisational design decisions can best promote this type of integration in the specific context of SCRM. For example, Munir et al. (2020) study the effect of sharing information and joint decision-making across departments on SCRM, though they do not mention which organisation design options to use (e.g., vertical communication and joint decision-making by higher-level managers or horizontal communication and delegation of decision power to lower levels of the hierarchy). These authors also presume that the work performed by the organisation is always divided across specialised departments, though other organisational designs are possible. Therefore, studying the impact of alternative organizational design choices that may promote internal integration for SCRM represents a critical development for this field.

The fourth theoretical contribution of the current research is that it sheds light on the specificities of SMEs in SCRM by using data from SMEs in the Spanish agri-food sector. Current studies on SCRM have mainly focused on large firms and, as a result, it is relatively unclear how SMEs can effectively manage supply chain risks (Gurbuz et al., 2023). As we all witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic that SMEs struggled more with supply chain disruptions than large companies (Gurbuz et al., 2023; Wieczorek-Kosmala, 2021), this research contributes to a small but steadily growing number of SCRM studies from the perspective of SMEs.

Finally, this research contributes to the organisational design literature by highlighting the potential of the interaction between structural and cultural elements of organisations. While some previous work has commented on the direct impact of one element on the other, the beneficial effects of their combination have rarely been commented on (Reigle, 2001). This study provides a theoretical elaboration and empirical evidence of this effect, opening a new path of research for the organisational design literature.

6.2Implications for professionalsOur work also provides some recommendations for professionals. We suggest managers should assess the levels of risk their organisations face and consider whether their organisational structures and cultures are organic enough to facilitate risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation along the supply chain. Organisations need to ensure they feature enough organic characteristics (at structural and cultural levels) to promote supply chain risk mitigation. However, organisations that focus on efficiency might find that organic characteristics interfere with their competitiveness. To deal with risk, they can maintain more mechanistic characteristics but still combine them with organic risk management substructures, driven by an organic culture. For example, they might create risk management committees or teams that include various specialists, to ensure horizontal communication and decision-making. Companies also should ensure that workers dealing with risk management are sufficiently committed to the companies, have sufficiently broad training and education and are proactive. The organic culture created by such workers promotes supply chain risk mitigation, especially if they can operate within an organic structure or substructure, such as the committees mentioned previously.

6.3Limitations and further researchThis research is not without limitations, which in turn are avenues for further research. First, our Harman test showed that common bias was not a problem, but we measure the variables using perceptual scales, rather than objective data. Data about organisational design parameters, such as the number of departments, hierarchical levels or the number of specialisation functions in a company, might offer effective alternative measures of certain structural organisational design parameters (Sine et al., 2006). Second, to assess the level of contextual risk, we measured the level of threat emanating from the supply chain (customers, competitors, suppliers). This measure does not explicitly account for the potential impacts of other contextual variables, such as technological complexity, which has been linked to organisational design (Woodward, 1958). The use of other risk measures, such as external threats to the supply chain (e.g., natural disasters, pandemics, technological complexity) also could provide extended insights. Third, we acknowledge that additional variables might moderate the predicted effects, such as the disaggregated level of risk in each area of the supply chain (upstream, downstream, internal) or cost–benefit trade-offs in implementing different strategies. Including such variables would help advance and enrich the research discussion.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCarmen González-Zapatero: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Javier González-Benito: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Son Byung-Gak: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Gustavo Lannelongue: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology.

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and by Spanish National Investigation Agency (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and by the European Union through grant PID2022-136496NB-I00.