Lung cancer small bowel metastases are rare.1 Their diagnosis is difficult, as most of them are asymptomatic, although they can sometimes cause symptoms related to complications. In the presence of abdominal symptoms in patients with lung cancer, we should suspect a lung cancer small bowel metastasis.2,3

We describe 2 cases of patients with acute abdomen secondary to lung cancer small bowel metastasis.

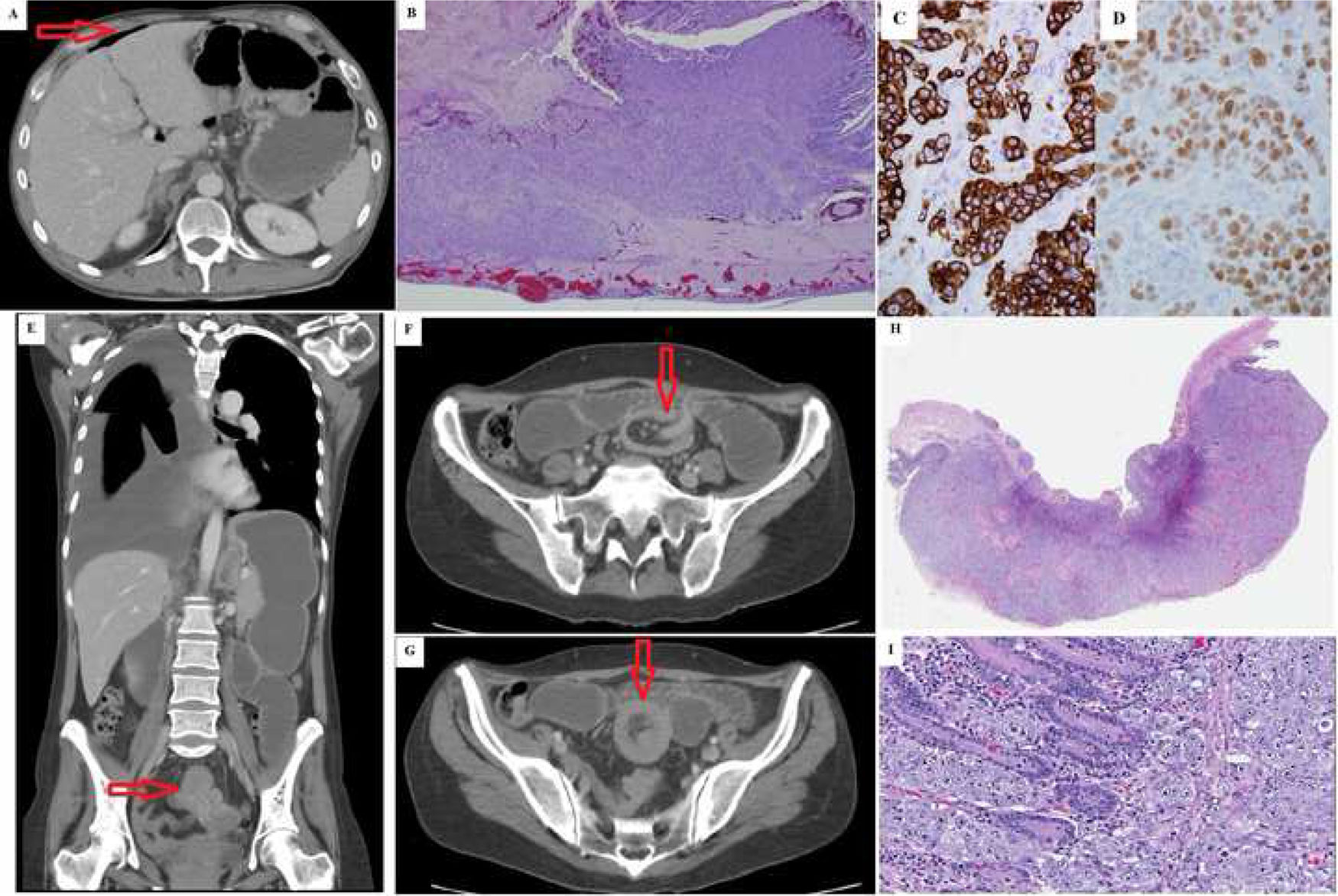

Case 158-year-old male, smoker, who presented in the Emergency Room for a seizure. Bilateral supratentorial masses consistent with brain metastases were observed on the brain computed tomography (CT). The chest-abdomen-pelvis CT revealed a pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe infiltrating the pleura, with mediastinal and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy. On° day 7, a CT scan was performed for abdominal pain, which revealed pneumoperitoneum, distension of the small bowel loops and free fluid (Fig. 1A). Urgent surgery was performed, in which a perforated jejunal tumour and generalised peritonitis were observed. Segmental resection and anastomosis were performed. Subsequently, CT-guided chest puncture histology revealed a lung adenocarcinoma. The patient was discharged 8 days later without complications (Clavien 0, CCI: 0). The histological study of the small intestine showed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma consistent with pulmonary origin (Fig. 1B and C). The patient died 2 months after surgery due to tumour progression (Clavien V, CCI: 100).

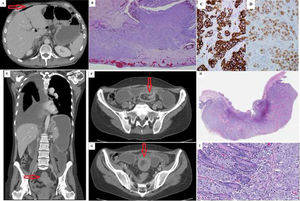

A) Case 1 abdominal CT axial slice: pneumoperitoneum (arrow). B) Case 1 histology: wall of the small intestine infiltrated by the tumour. Infiltration from the peritoneal layer towards the mucosa, in which small tumour nests, ulceration and surface necrosis are observed. C) Case 1 immunohistochemistry. Positivity for cytokeratin 7 in the membrane and cytoplasm in the tumour. D) Case 1 immunohistochemistry. Positive TTF-1 in the infiltrating tumour. E–G) Case 2 abdominal CT: small intestine invagination (arrow). H) Case 2 histology: panoramic view of the ulcerated intestinal wall infiltrated by adenocarcinoma throughout its thickness. I) Case 2 histology: sheet-like growth of the neoplasm, forming solid nests, cells with the presence of intracytoplasmic vacuoles and cell lumina.

A 46-year-old woman, on immunotherapy with nivolumab for undifferentiated stage IV carcinoma of unknown origin, stable for one year. She was hospitalised for general malaise and vomiting. Intestinal obstruction secondary to jejunal invagination was observed on the abdominal CT (Fig. 1E–G). The surgery confirmed invagination, with a palpable and indurated lesion inside, with no further findings; segmental resection and anastomosis were performed. The histological result was infiltration due to lung adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1H and I). The patient presented with deep vein thrombosis and acute respiratory failure secondary to pleural effusion (Clavien IIIb, CCI: 33.5). She was readmitted one month later for pleural effusion. She received palliative treatment and subsequently died (Clavien V, CCI: 100).

Approximately 50% of lung cancer patients have metastases at diagnosis2 and the incidence of locoregional or distant recurrence after treatment is 50% at 2 years.4 Lung cancer can spread lymphatically or haematogenously; the liver, brain, adrenal gland and bone are the most common locations,2–5 although dissemination patterns vary according to histological type.5

Metastatic involvement in other locations is rare (less than 5%), is more frequent in men and usually presents with multiple lesions.2,3 It usually appears in terminal patients with disseminated disease in several locations.2–4 Of these lesions, gastrointestinal lesions have an incidence of 0.3%–1.7%1, and are located, in order of frequency, in the oesophagus, small intestine, stomach and colon.1,3 In the small intestine, they predominantly affect the jejunum-ileum, as in our patients, and to a lesser extent the duodenum.1,3

The clinical manifestations of lung cancer small bowel metastases are usually rare or confused with the gastrointestinal effects of chemotherapy. In fact, in post mortem studies, their incidence increases to 4.6%–14%.1 In rare cases, the first clinical manifestation of lung cancer is due to gastrointestinal metastatic involvement.1,2 Symptomatic intestinal metastases due to complications such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation or obstruction have been described.1,3 Therefore, in patients with acute abdomen and lung cancer, they should be considered in the differential diagnoses.1,3

The most appropriate treatment for intestinal metastases is under debate and is influenced by the clinical picture. In the case of complications, as in our patients, the recommended treatment is surgery, with segmental intestinal resection and anastomosis. In the case of invagination, previous disinvagination should be avoided due to the risk of neoplastic spread, perforation and complications in the anastomosis caused by manipulation.1

Gastrointestinal metastases in lung cancer worsen the prognosis and reduce survival.2 The presence of intestinal perforation, other extraintestinal metachronous metastases and age are factors that tend to indicate a poorer prognosis. In these cases, survival is usually a question of weeks or months.1,3

Lung cancer small bowel metastases are rare and mostly asymptomatic. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion is required to make the right diagnosis. Their appearance is associated with a worse prognosis and lower survival.

Please cite this article as: Picardo Gomendio MD, Manuel Vázquez A, Garcia Amador C, Rodrigues Figueira Y, Candia A, de la Plaza Llamas R, et al. Causa rara de abdomen agudo: metátasis intestinales de cáncer de pulmón. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:656–658.