Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), or Hughes syndrome, is an acquired autoimmune thrombophilia characterised by venous or arterial thrombosis and/or recurrent miscarriages due to the presence of autoantibodies to phospholipid-binding plasma proteins, such as the lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody (aCL), and the anti-beta-2-glycoprotein antibody (aβ2GPI).1 There are some primary forms that are not associated with another autoimmune disease. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a severe and rapidly progressive form that affects multiple organs simultaneously and causes multiple organ failure. Microangiopathy is more commonly found in CAPS than in the classic APS form.2 CAPS, with a mortality rate of nearly 50%, accounts for less than 1% of all cases of APS.2 CAPS presenting as ischaemic colitis is extremely rare, and although treatment is initially medical, surgery may be required in some cases2–4 (Table 1).

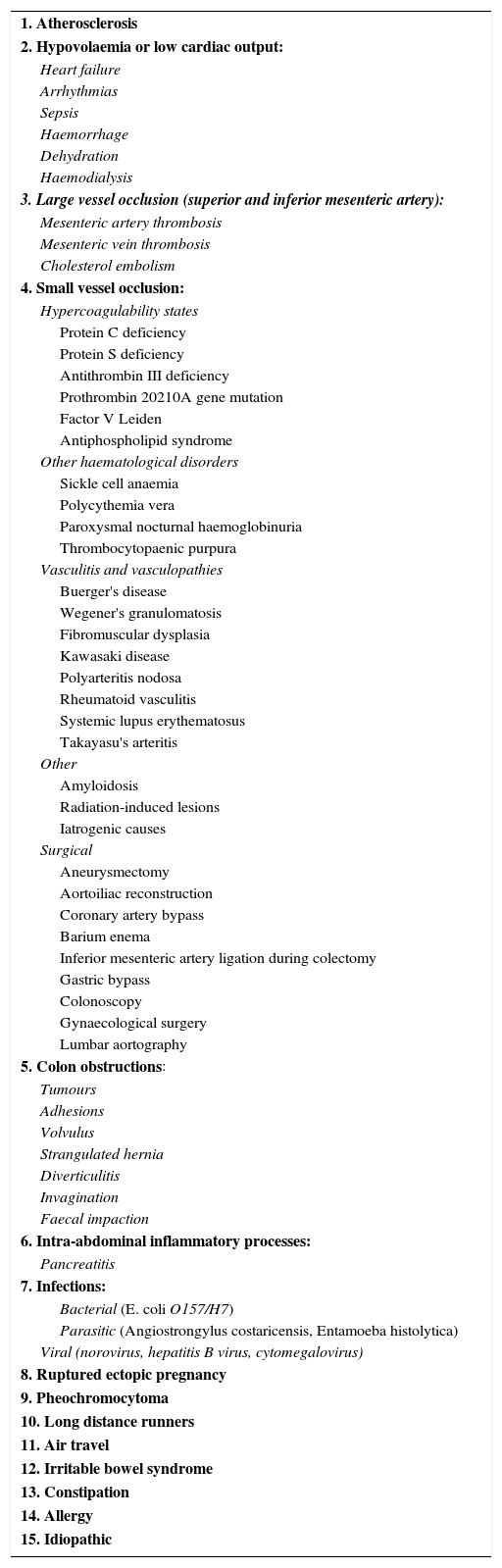

Causes of ischaemic colitis.

| 1. Atherosclerosis |

| 2. Hypovolaemia or low cardiac output: |

| Heart failure |

| Arrhythmias |

| Sepsis |

| Haemorrhage |

| Dehydration |

| Haemodialysis |

| 3. Large vessel occlusion (superior and inferior mesenteric artery): |

| Mesenteric artery thrombosis |

| Mesenteric vein thrombosis |

| Cholesterol embolism |

| 4. Small vessel occlusion: |

| Hypercoagulability states |

| Protein C deficiency |

| Protein S deficiency |

| Antithrombin III deficiency |

| Prothrombin 20210A gene mutation |

| Factor V Leiden |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome |

| Other haematological disorders |

| Sickle cell anaemia |

| Polycythemia vera |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria |

| Thrombocytopaenic purpura |

| Vasculitis and vasculopathies |

| Buerger's disease |

| Wegener's granulomatosis |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia |

| Kawasaki disease |

| Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Rheumatoid vasculitis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Takayasu's arteritis |

| Other |

| Amyloidosis |

| Radiation-induced lesions |

| Iatrogenic causes |

| Surgical |

| Aneurysmectomy |

| Aortoiliac reconstruction |

| Coronary artery bypass |

| Barium enema |

| Inferior mesenteric artery ligation during colectomy |

| Gastric bypass |

| Colonoscopy |

| Gynaecological surgery |

| Lumbar aortography |

| 5. Colon obstructions: |

| Tumours |

| Adhesions |

| Volvulus |

| Strangulated hernia |

| Diverticulitis |

| Invagination |

| Faecal impaction |

| 6. Intra-abdominal inflammatory processes: |

| Pancreatitis |

| 7. Infections: |

| Bacterial (E. coli O157/H7) |

| Parasitic (Angiostrongylus costaricensis, Entamoeba histolytica) |

| Viral (norovirus, hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus) |

| 8. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

| 9. Pheochromocytoma |

| 10. Long distance runners |

| 11. Air travel |

| 12. Irritable bowel syndrome |

| 13. Constipation |

| 14. Allergy |

| 15. Idiopathic |

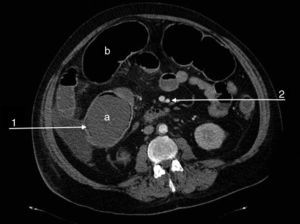

We present the case of a 47-year-old man, an active smoker and former drinker with a personal history of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, complete occlusion of the left common carotid and right posterior cerebral arteries, amputation of both lower limbs due to ischaemia, carrier of the prothrombin gene mutation (G20210A) and MTHFR gene mutation, with hypercoagulability syndrome and hyperhomocysteinaemia. He was undergoing tests for suspicion of APS. The patient was admitted to the emergency department due to a flare-up of chronic abdominal pain in the previous 48h. The physical examination showed abdominal distension with absent bowel sounds and signs of peritoneal irritation. Of note in the urgent laboratory test findings were: leukocytosis (16,500/μl) with neutrophilia (91%), thrombocytopaenia (85,000/μl), elevated CRP (132mg/l), creatinine (2.5mg/dl) and urea (97mg/dl), and low haemoglobin (9.8g/dl). The patient's condition deteriorated rapidly, with criteria for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Abdominal-pelvic CT angiography showed dilation of the transverse colon and caecum (9cm), increased parietal uptake in the sigmoid and pneumatosis intestinalis, with patent coeliac trunk, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and renal arteries (Fig. 1). Urgent colonoscopy revealed extensive mucosal ischaemia, and urgent immunological tests showed elevated aCL IgM (12MPLU/ml; positive: >10MPLU/ml) and fibrinogen (583mg/dl; normal: 200–400mg/dl), negative for aβ2GPI IgM and Russell test. Given the suspicion of severe ischaemic colitis secondary to CAPS, treatment with corticosteroids (methylprednisolone: 200mg/day) and enoxaparin 100mg/24h was started. In view of his haemodynamic instability, the patient underwent emergency surgery, which revealed ischaemic colitis extending along the length of the colon and the distal ileum. Pancolectomy with a Brooke ileostomy was performed. The patient died 24h after surgery. The full results of the autoimmunity study showed, a posteriori, an increase in aCL IgG (43GPLU/ml; positive: >10GPLU/ml), aβ2GPI IgG (86U/ml, positive: >10U/ml) and factor VIII (198.30%; normal: 50–150%). Tests for lupus anticoagulant, plasminogen, anticoagulant protein C, free and total protein S, 2-antiplasmin and functional antithrombin III were negative. The positivity of antibodies aCL and anti-β2 GPI, together with anatomopathological findings of acute-subacute intestinal ischaemia with mucosal and submucosal necrosis and thrombosed medium-sized arteries confirmed the initial suspicion of CAPS.

The diagnostic criteria of CAPS, which was first described by Asherson in 1992, are shown in Table 2.5 It is the first symptom of APS in 56.4% of patients with no previous history of thrombosis, and precipitating factors, such as infection, previous surgery/traumas, use of oral contraceptives or the presence of neoplasms, can be identified in 53% of cases.2,5 Renal involvement is most frequent (78%), followed by lung (66%), central nervous system (56%) and heart and skin (50%) manifestations.2 Gastrointestinal involvement, such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, pancreatitis, and hepatic or splenic thrombosis is rare, and the hollow viscus necrosis presented in our patient is exceptional.2,6,7

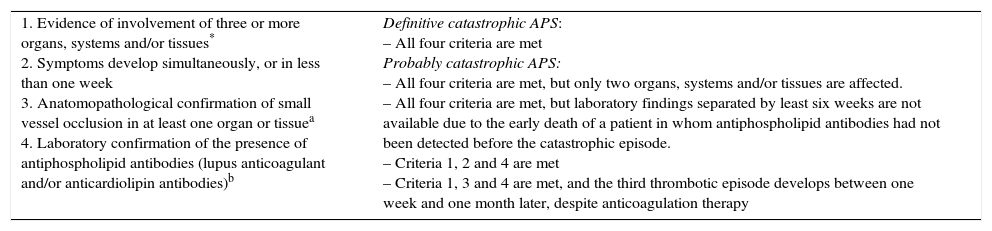

Preliminary diagnostic criteria of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome.

| 1. Evidence of involvement of three or more organs, systems and/or tissues* 2. Symptoms develop simultaneously, or in less than one week 3. Anatomopathological confirmation of small vessel occlusion in at least one organ or tissuea 4. Laboratory confirmation of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant and/or anticardiolipin antibodies)b | Definitive catastrophic APS: – All four criteria are met Probably catastrophic APS: – All four criteria are met, but only two organs, systems and/or tissues are affected. – All four criteria are met, but laboratory findings separated by least six weeks are not available due to the early death of a patient in whom antiphospholipid antibodies had not been detected before the catastrophic episode. – Criteria 1, 2 and 4 are met – Criteria 1, 3 and 4 are met, and the third thrombotic episode develops between one week and one month later, despite anticoagulation therapy |

Generally, clinical evidence of vascular occlusion confirmed by imaging techniques, when appropriate. Kidney involvement is defined as a 50% increase in plasma creatinine, severe systemic hypertension (>180/100mmHg) and/or proteinuria (>500mg/24h).

For anatomopathological confirmation, signs of thrombosis must be present, although vasculitis may sometimes also be present.

If the patient had not previously been diagnosed with APS, laboratory confirmation requires a finding of antiphospholipid antibodies on two or more separate occasions, at least six weeks apart (not necessarily at the time of the thrombotic accident), according to the preliminary criteria proposed for the classification of definitive APS.

In contrast to previous studies,2 where APS is associated with acute kidney failure, acute heart failure and skin manifestations, our patient had a history of thrombosis and colonic involvement (fulminant ischaemic colitis). A definitive diagnosis of CAPS was obtained from the analytical findings, anatomopathological changes, and the presence of the four clinical criteria indicated. There is no consensus with regard to the optimal therapeutic approach to CAPS.7,8 The combination of intravenous heparin, high doses of IV corticosteroids, immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis is the basic treatment of choice (evidence level II), and can reduce mortality from 50% to 30%.8 In our patient, plasmapheresis was not initiated due to rapid multiorgan deterioration. The indications for surgery are the same as in all cases of ischaemic colitis: massive haemorrhage, perforation or fulminant colitis. The extent of the resection will depend on the distribution of the lesions, and primary anastomoses should be avoided due to the risk of surgical wound dehiscence. Special cases include fulminant pancolitis, as in this case, that require total colectomy with ileostomy.2 Forty-four per cent (44%) of the patients on the CAPS register died, with the leading cause of death being brain involvement, followed by cardiac manifestations and sepsis, which is considered an independent risk factor.3,9

Please cite this article as: González Puga C, Lendínez Romero I, Palomeque Jiménez A. Colitis isquémica grave como presentación del síndrome por anticuerpos antifosfolípidos catastrófico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:684–687.