Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome (CCS), is a multisystem disease characterised by asthma, eosinophilia in peripheral blood and tissues, formation of extravascular granulomas and vasculitis of small and medium-sized blood vessels.1 It is a rare disease with a prevalence of 10.7–13 cases per million. The organ most commonly affected is the lung. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract may be involved in 20–50% of patients, but clinical presentation with GI symptoms is uncommon.2

We present the case of a patient with EGPA whose clinical signs were suggestive of colitis.

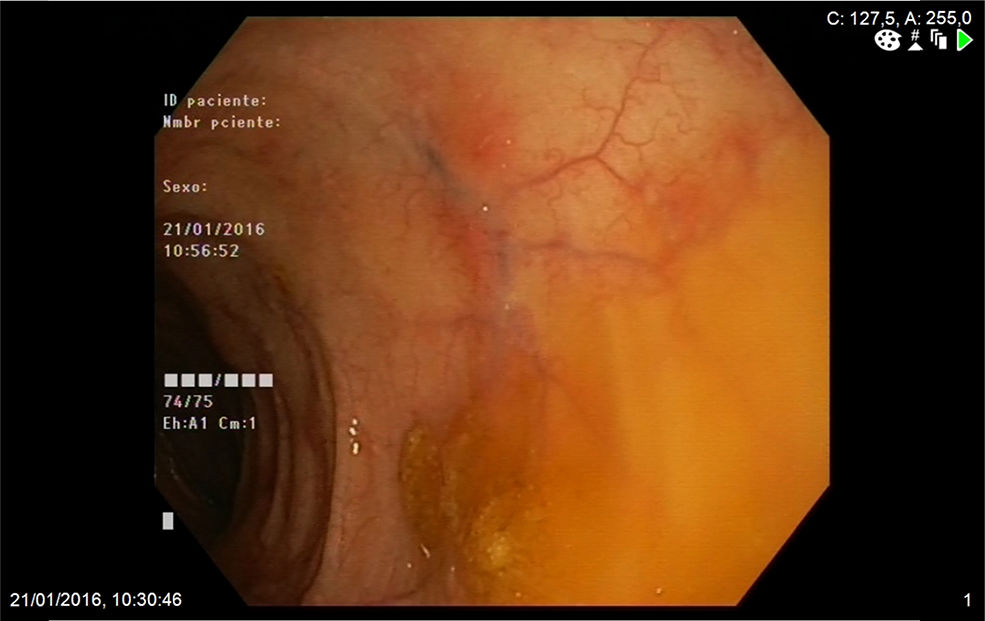

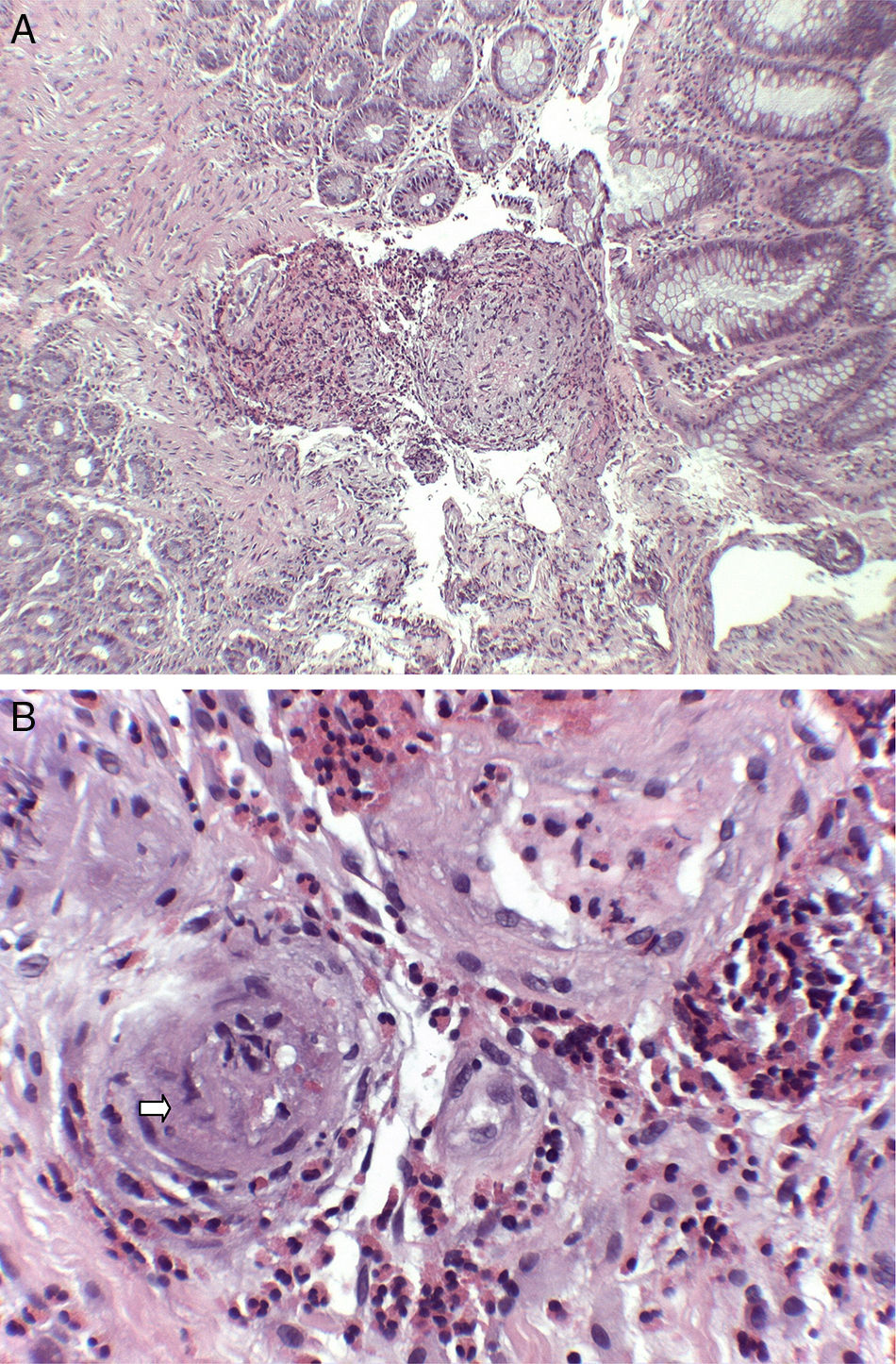

A 74-year-old woman was admitted to our department with a two-month history of six to seven episodes of diarrhoea per day with blood and mucus and abdominal pain. She reported that in the previous two weeks she had also had a cough with greenish expectoration but no fever. Her personal history included a history of late-onset asthma, bronchiectasis, rhinitis and maxillary sinusitis. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and the only finding of note was the crackles heard in both lung bases. Blood analysis showed leucocytosis, with eosinophils 47%, C-reactive protein 13.4mg/l (0.03–5) and total IgE 271kU/l (1.3–165). The peripheral blood smear only showed eosinophilia. The other investigations, including kidney and liver function tests, urinalysis and vitamin B12 levels, showed normal values. Antinuclear antibodies were positive at the 1:320 titre (speckled pattern) and myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (MPO-ANCA) were negative. Faeces were tested for parasites and a Mantoux test was performed, with both being negative. The chest x-ray showed the presence of interstitial infiltrates in both lung bases. Investigations were completed with an echocardiogram, which showed minimal pericardial effusion; a chest computed tomography scan, which showed bilateral lung involvement, with areas of subpleural consolidations and predominantly peripheral ground-glass opacities; and a colonoscopy, which showed patchy erythematous areas in the left colon with abundant mucoid secretion, from which biopsies were taken (Fig. 1). The colon biopsy report described a congested lamina propria with numerous eosinophils and submucosa with a predominantly eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate of perivascular distribution (Fig. 2A), as well as some occlusion of vascular lumens and areas of suspected fibrinoid necrosis (Fig. 2B). In view of the findings of asthma, sinusitis, eosinophilia, lung infiltrates and colon biopsy with vasculitis and marked eosinophilia, the patient was diagnosed with EGPA and started on treatment with prednisone 1mg/kg/day. The patient was followed up in the outpatient clinic and had a good clinical and analytical response, being able to start reducing the steroids at 6weeks and starting treatment with azathioprine at 14weeks.

Histological findings (haematoxylin and eosin staining): (A) submucosa with predominantly eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate with perivascular distribution and marked thickening of the vascular walls (H&E ×40). (B) At higher magnification, the permeation of vascular walls by the infiltrate is highlighted, with occlusion of some vascular lumens (arrow) (H&E ×200).

EGPA is a systemic vasculitis that belongs to the ANCA-associated vasculitis group of diseases. Despite its classification, ANCAs are only detected in 30–40% of patients with EGPA. The clinical manifestations develop in several phases: a prodromal phase with symptoms of atopy; an eosinophilic phase characterised by peripheral and tissue eosinophilia; and a vasculitis phase, involving signs of vasculitis affecting multiple organs such as the skin, the nervous system, the heart, the kidney and the GI tract.3 The American College of Rheumatology propose six criteria for defining EGPA: asthma; peripheral eosinophilia greater than 10%; paranasal sinus abnormality; non-fixed pulmonary infiltrates; mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy; and a biopsy containing a blood vessel in which accumulation of eosinophils is identified in extravascular areas. Four or more of these criteria have to be met to establish the diagnosis, with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.7%.4 In the case of our patient, five of these criteria were met; plus, the colon biopsy revealed extravascular eosinophilic infiltration and signs of vasculitis. The findings of vasculitis may be lacking because the biopsies are from superficial areas that do not contain submucosal vessels, or because the patients have not progressed from the eosinophilic phase to the vasculitis phase. It is also important to highlight that biopsies from areas with mild involvement or areas that are even normal endoscopically may show eosinophilic infiltration which help us to establish the diagnosis.5

In EGPA, GI tract involvement can develop in either the eosinophilic phase or the vasculitis phase, and any section of the tract may be affected. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain (59%), diarrhoea (33%) and bleeding (18%). The large intestine is more commonly affected than the small intestine.6 In the past, small intestine involvement was often detected during emergency surgery to treat a perforated bowel. Now, however, the use of techniques such as capsule endoscopy or double-balloon enteroscopy enables early diagnosis of some cases of EGPA, which present as ulcerations in the small intestine.7,8 More severe forms of presentation with ischaemia, perforation or intestinal obstruction are associated with poor prognosis. The mortality rate associated with GI involvement in EGPA lies in fourth place behind cardiac, neurological and renal involvement. Treatment is based on corticosteroids (prednisone at doses of 0.5–1.5mg/kg/day) for 6–12 weeks with subsequent gradual reduction. In the most severe forms, cyclophosphamide may be required initially. Once remission is induced, as with our patient, maintenance treatment is based on less toxic immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine or methotrexate, combined with descending doses of corticosteroids for 12–18 months.

In conclusion, EGPA is a rare vasculitis that can affect the GI tract. Presentation with GI symptoms is uncommon and the clinical signs can range from mild symptoms to severe manifestations. The diagnosis of EGPA in the GI tract requires a high degree of clinical suspicion, as a documented histological finding of vasculitis may be lacking and the only indicative finding may be the presence of extravascular eosinophilia.

Please cite this article as: Ameneiros-Lago E, Pérez-Valcarcel J, Fernández-Fernández FJ, Caínzos-Romero T. Colitis como forma de presentación de una granulomatosis eosinofílica con poliangitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:302–304.