Choledochal cysts (CCs) are rare abnormalities of the bile duct (BD) that are more commonly found in children, women and Asians.1 We present a case of type II CC (CCII): saccular outpouchings arising from the supraduodenal extrahepatic bile duct, account for 0.8–5%, according to the classification system devised by Todani.2 We performed a literature search in PubMed with no limits for articles published up to 30 April 2016 using the following terms: ([Choledochal Cyst type II] OR [Choledochal Cyst type 2] AND [Laparoscopy] OR [Therapeutics]). The search retrieved 50 articles. A review of the abstracts and body text of the articles showed that in the series in which they are included, CCII are the least frequent form of choledochal cysts.

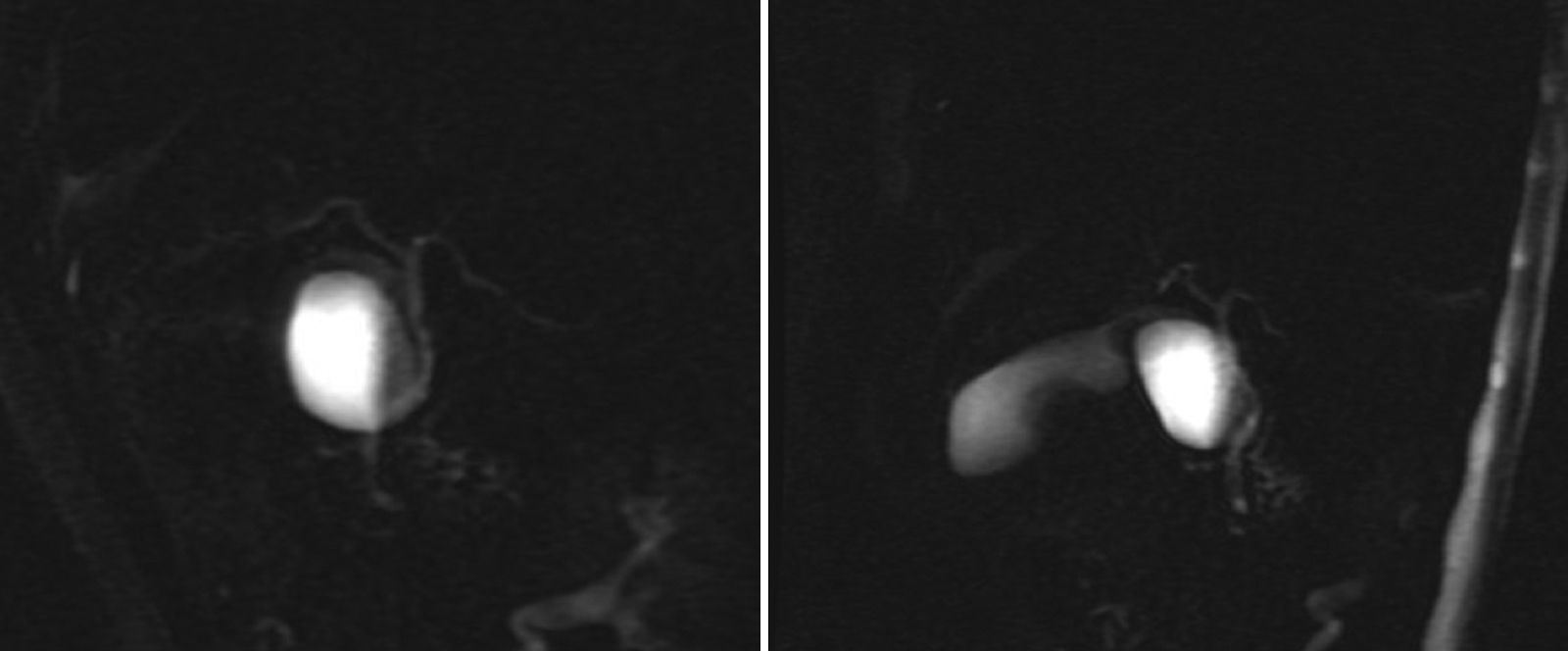

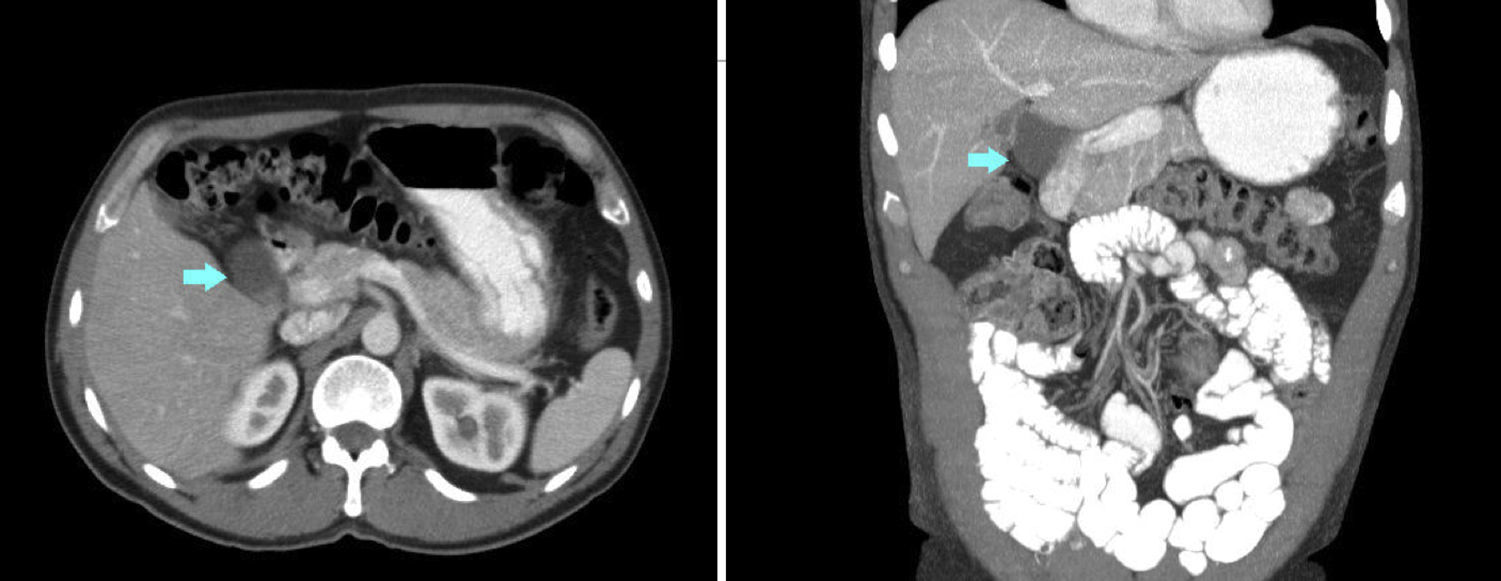

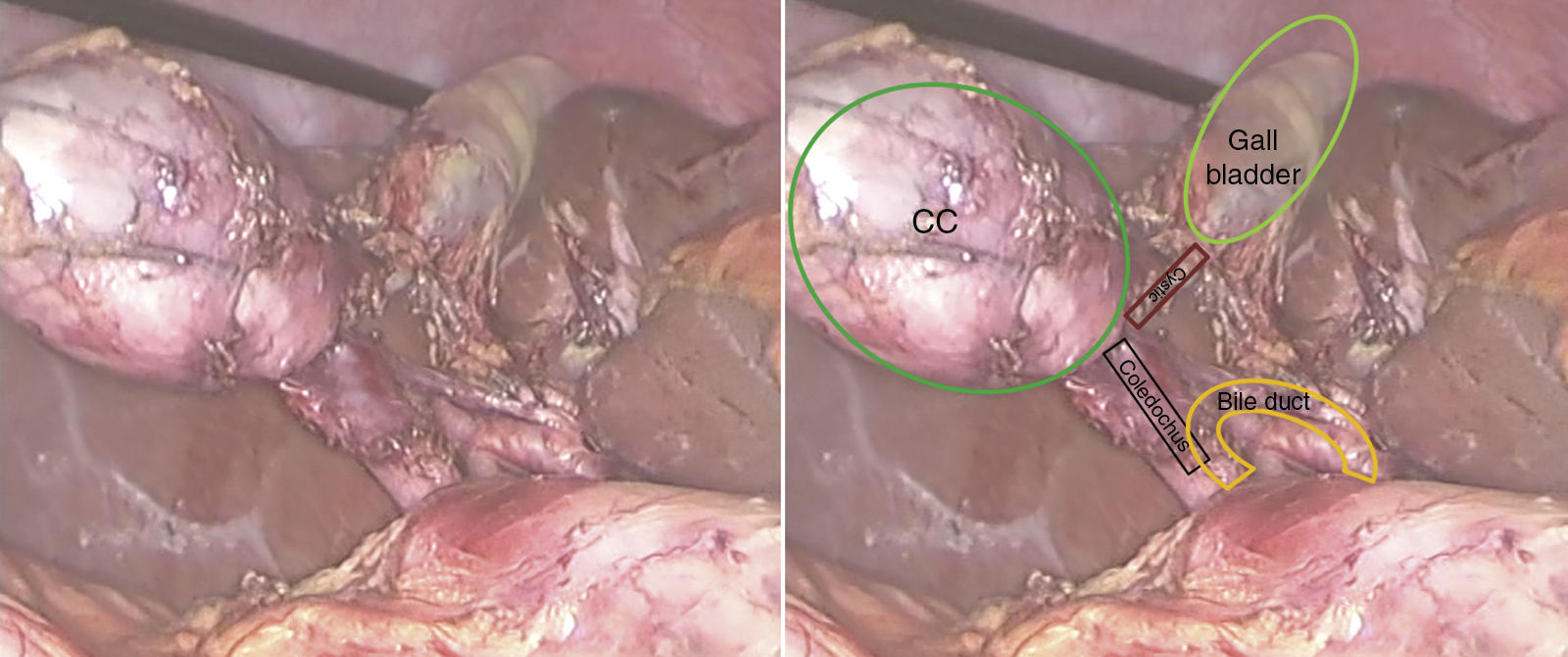

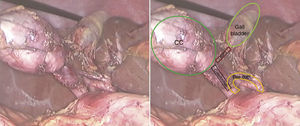

A 53-year-old man presented with epigastric pain, radiating to the back. Laboratory tests were normal. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) revealed biliary lithiasis measuring 2cm and CC measuring 38mm. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed: vesicular lithiasis, CC measuring 38×35mm in the lateral wall of the proximal third of the common bile duct (Figs. 1 and 2). A scheduled laparoscopy was performed with the patient in the French position. Pneumoperitoneum was induced using a Veress needle. Trocar placement was as follows: supraumbilical for optic (10mm), right lateral (5mm), epigastrium (5mm) and left lateral (5mm) trocars. CC adhesions to the liver, gallbladder and bile duct were released and dissected, leaving a 2mm stump that was stapled and sectioned, completing excision of the cyst (Fig. 3). Following this, cholecystectomy was performed. The patient was discharged after 2 days. The histological examination of the specimen showed: cystic formation with a wall of dense fibrous connective tissue with some glands of biliary appearance with no muscle layers and with flattened epithelial lining, with no cell abnormalities. The specimen was negative for tumour markers. At the 24-month follow-up, there was no evidence of altered liver or bile duct function.

CCs, which are rare dilations of the biliary tree, are more frequent in Asian populations (1/13,000 Japanese), compared with an incidence of 1/100,000 in Western individuals.3 Although 80% of cases are diagnosed in childhood, the latest published series suggest that incidence in adults is increasing.3,4

CCs were first described by Vater and Ezler in 1723.3 Alonzo-Lej et al. devised a classification system that was subsequently modified by Todani et al.5 CCIIs, defined as saccular outpouchings arising from the supraduodenal extrahepatic bile duct, are the rarest type of bile duct cyst.1 Their aetiology is unknown, with a reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the biliary tree due to an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct union being described as possibly leading to biliary dilatation.3

The most serious complication is malignant transformation (5–10% of CCs).6 Carcinogenesis has been attributed to reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the bile duct, cholestasis and recurrent infections. Incidence of malignant transformation is higher in type I, IV and V CCs compared with types II and III.1,4

In children, symptoms are nonspecific, with abdominal pain and vomiting. Jaundice, particularly if prolonged after the neonatal period, or abnormalities on liver function tests facilitate early diagnosis.6 The classic triad of jaundice, abdominal mass and pain in the right hypochondrium occurs in 1/3 of children.3 In adults, CCs present with pain in the right hypochondrium, which is attributed to calculi. For this reason, 40% of patients undergo cholecystectomy before diagnosis.1

CCs are diagnosed with: ultrasound examination, usually the first test performed,4 and CT scan can be used to detect the presence of hepatic or pancreaticobiliary disease as the cause of biliary dilation.7 The most effective diagnostic test is currently magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, a non-invasive test that avoids the risks associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiopancreatography (PTC). This test can accurately define the anatomy of the bile duct (BD), thus permitting differential diagnosis with gallbladder duplication and duodenal duplication cysts.

The treatment of choice is total excision using different techniques according to the type of CC. In type III (choledochocele), however, endoscopic sphincterotomy is preferred,8,9 since partial resection can lead to complications and recurrence. Laparotomic surgery is the traditional approach, but laparoscopy is gaining ground as surgeons perfect their skills in this technique.10 In theory, the drawbacks of laparoscopy include: incomplete excision of the CC or, if malignancy exists, potential abdominal dissemination.9

A recent study classified CCIIs according to their location with respect to the hepatoduodenal ligament (upper, middle and lower part of the extrahepatic biliary tree) in order to determine the appropriate surgical management.11

Possible treatment approaches in CCIIs were: excision of the extrahepatic bile duct and hepaticojejunostomy or complete excision of the CC with primary closure over a T-tube, since communication between the BD and CC does not allow primary closure.4 However, when the cyst is connected to the common duct through a very thin neck, as in our patient, complete excision of the CC and ligation of the neck is possible.2,7

In the latest published series, the authors recognise that the type of clinical presentation can predict the need for a more complex approach, and complete resection was only possible in half of their patients.11

In conclusion, CCs are rare in non-Asian populations. The incidence in adults may be increasing, so they should be considered in adults presenting with abdominal pain and dilation of the bile duct.3,4 The treatment of choice is complete resection, and laparoscopy is a viable option.

Please cite this article as: López-Marcano A, de la Plaza-Llamas R, Ramia JM, Al-Shwely F, Gonzales-Aguilar J, Medina Velasco A. Abordaje laparoscópico del quiste de colédoco tipo II. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:678–680.