Humans, the only definitive host, contract taeniasis by consuming raw or undercooked pork or beef infected with the cysticercus, which takes two to three months to develop into an adult tapeworm in the intestine.1 Although cases are isolated and not very common, this infection is autochthonous in Spain. However, it is not considered a public health problem as only sporadic cases imported from low-income countries have been identified.2,3

In April 2015, an eight-year-old girl from Valencia (Spain) was found to have whitish structures in her underwear. The girl was administered mebendazole 20mg/ml for four days, which was repeated at two weeks by medical prescription against worm infestations. This treatment was repeated in July and October 2015 without eliminating the structures. Metronidazole 125mg/5ml, three times a day for one week was prescribed. Given the persistence of the structures, another paediatrician was consulted, who recommended the administration of a single dose of pyrantel 11mg/kg for four days followed by coprological analysis. The analysis, which was performed in November 2015, was positive for “dog tapeworm”, or Dipylidium caninum, infestation. The paediatrician recommended treatment either with niclosamide or praziquantel. Given the unusual and foreign nature of the medication requested, the pharmacist referred the child to the Department of Parasitology of the University of Valencia's Pharmacy Faculty, where three serial stool samples and three pieces of adhesive tape (Graham's test) were analysed on consecutive days.

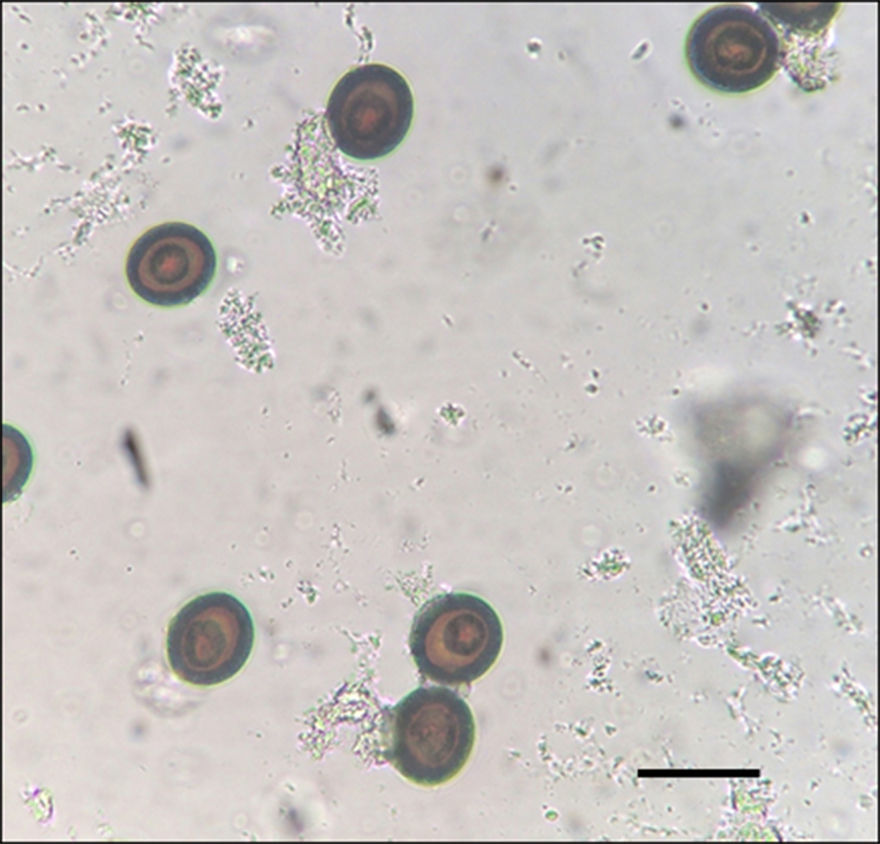

The macroscopic observation of numerous isolated long whitish structures (11.4–13.7×4.0–4.4mm) was suggestive of Taenia proglottids. The faecal analysis revealed the presence of multiple yellowish-brown spherical eggs with a thick shell, measuring 35.0–37.5μm in diameter, which were radially striated and contained a six-hooked embryo (hexacanth) known as an oncosphere. Graham's test was negative for pinworm eggs (Enterobius vermicularis), although multiple Taenia eggs were identified (Fig. 1). The microscopic analysis of a proglottid, mounted with Amann's lactophenol between two slides, confirmed the presence of multiple (more than 15) primary lateral branches on either side of the central uterine axis (Fig. 2), with the genital pore located on the side, confirming the diagnosis of Taenia saginata/Taenia asiatica. The girl's parents and her twin sister had no parasitic infestation. The oral administration of 50mg/kg of paromomycin sulfate divided over three doses/day was prescribed after identification of the cestode in December 2015. The parasitology stool tests conducted in January and February after treatment were negative.

The eggs in the faeces were identified as the genus Taenia. Specific identification was confirmed by analysis of the gravid proglottids with permanent staining or with lactophenol, to reveal the number of lateral uterine branches or to ascertain whether the proglottids spontaneously emerged from the anal orifice or were eliminated with faeces. The case in question without doubt concerns T. saginata/T. asiatica as both species have the same morphological characteristics,4 and they can only be differentiated by molecular methods.5–7

The child may have become infected during a stay in France, as her parents said that they went to visit her grandparents in February 2015, who regularly eat steak tartare (raw beef mixed with raw egg yolk and spices). This information may be relevant when it comes to establishing the epidemiological chain of the case given that the girl's French grandfather was treated for taeniasis two years previously. Furthermore, identifying France as the possible source of infection is not surprising given that the estimated mean annual prevalence of human taeniasis in the country is 0.11%.8

The girl's lack of symptoms is consistent with other patients as the pathogenesis of taeniasis is very mild, with symptoms associated with abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhoea, nausea and anorexia.9 The finding of proglottids in the patient's underwear can be explained by the fact that T. saginata/T. asiatica can move independently, which means they can actively emerge without having to be passed. When the proglottids crack open upon leaving the body, their eggs can become adhered to the perianal area, which explains their detection in Graham's test.

Praziquantel (5–10mg/kg single-dose) and niclosamide (50mg/kg single-dose, up to a maximum of 2g) are the drugs of choice.10 The fact that both antiparasitics are considered to be foreign drugs meant that paromomycin sulfate had to be used as it is available in the pharmacies.11

It should be noted that cooking meat for longer or freezing it at −20°C for at least 12h would be sufficient to prevent infection.

FundingProject No. RD12/0018/0013, Red de Investigación Cooperativa en Enfermedades Tropicales (Tropical Diseases’ Cooperative Research Network, RICET), 4th National R&D&I Programme 2008-2011, ISCIII-Subdirección General de Redes y Centros de Investigación Cooperativa (Carlos III Health Institute—Subdirectorate General of Cooperative Research Centres and Networks) and FEDER (Spanish Federation of Rare Diseases), Ministerio de Salud y Consumo (Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs), Madrid, Spain.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz-Antolí C, Seguí R, Irisarri-Gutiérrez MJ, Toledo R, Esteban JG. Teniasis en una niña española. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:626–628.