Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with psychological morbidity, particularly anxiety and depression.1 In periods of remission, around 29–35% of patients suffer from anxiety or depression, while during flare-ups, rates climb to 80% for anxiety and 60% for depression.2,3 Both conditions have been significantly associated with a greater likelihood of relapse4 and worse quality of life, regardless of the severity of the IBD.5–7

The aim of the ENMENTE project was to analyse the psychosocial aspects of IBD and how they are managed.8 In this preliminary study, we wanted to find out the patients’ point of view on the psychosocial aspects of IBD, how they are treated in clinical practice and how they should be managed.

A focus group meeting was held with seven patients selected through the Confederación de asociaciones de enfermos de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa de España (ACCU España) [Confederation of Spanish Associations of Patients with Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] following a pre-established typology table. The subjects, four women and three men, were aged from 26 to 43 and had different sociocultural levels and occupations; five had Crohn's disease and two ulcerative colitis. Disease onset was less than two years previously in one patient, but over ten years previously in the other six. Disease severity varied, with four having had surgery, two of whom had a stoma. A discussion map was established, but free discussion was also encouraged; audio recordings were made, with the knowledge and authorisation of all those present. Notes were made on the subject being discussed on a white board for immediate confirmation from the group and the discussion was coded and reorganised using mind mapping software.

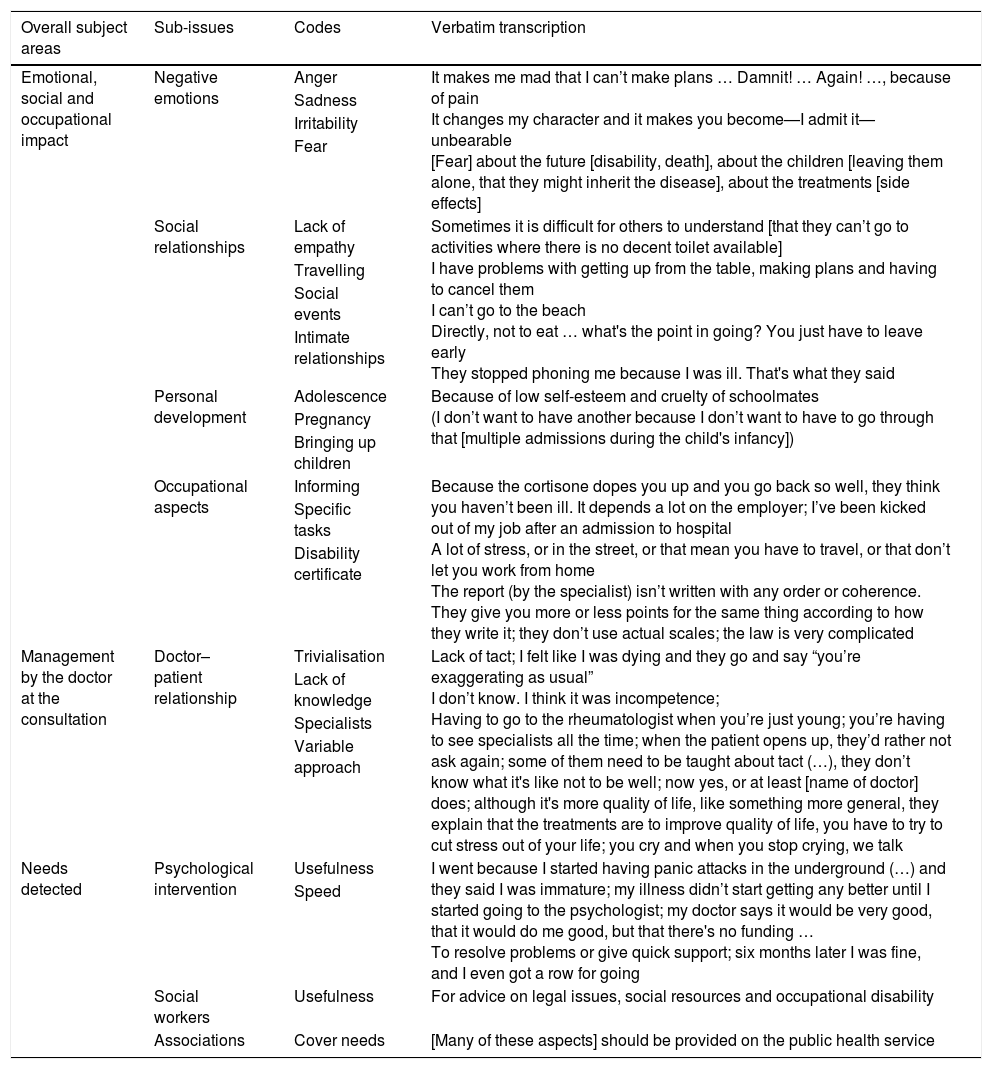

The subjects discussed covered three overall areas: (a) emotional, social and occupational impact; (b) management by the consulting doctor; and (c) needs detected. Table 1 shows examples taken from the discussion.

Verbatim transcriptions from the discussion ordered by subject area, sub-issues and codes.

| Overall subject areas | Sub-issues | Codes | Verbatim transcription |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional, social and occupational impact | Negative emotions | Anger | It makes me mad that I can’t make plans … Damnit! … Again! …, because of pain It changes my character and it makes you become—I admit it—unbearable [Fear] about the future [disability, death], about the children [leaving them alone, that they might inherit the disease], about the treatments [side effects] |

| Sadness | |||

| Irritability | |||

| Fear | |||

| Social relationships | Lack of empathy | Sometimes it is difficult for others to understand [that they can’t go to activities where there is no decent toilet available] I have problems with getting up from the table, making plans and having to cancel them I can’t go to the beach Directly, not to eat … what's the point in going? You just have to leave early They stopped phoning me because I was ill. That's what they said | |

| Travelling | |||

| Social events | |||

| Intimate relationships | |||

| Personal development | Adolescence | Because of low self-esteem and cruelty of schoolmates (I don’t want to have another because I don’t want to have to go through that [multiple admissions during the child's infancy]) | |

| Pregnancy | |||

| Bringing up children | |||

| Occupational aspects | Informing | Because the cortisone dopes you up and you go back so well, they think you haven’t been ill. It depends a lot on the employer; I’ve been kicked out of my job after an admission to hospital A lot of stress, or in the street, or that mean you have to travel, or that don’t let you work from home The report (by the specialist) isn’t written with any order or coherence. They give you more or less points for the same thing according to how they write it; they don’t use actual scales; the law is very complicated | |

| Specific tasks | |||

| Disability certificate | |||

| Management by the doctor at the consultation | Doctor–patient relationship | Trivialisation | Lack of tact; I felt like I was dying and they go and say “you’re exaggerating as usual” I don’t know. I think it was incompetence; Having to go to the rheumatologist when you’re just young; you’re having to see specialists all the time; when the patient opens up, they’d rather not ask again; some of them need to be taught about tact (…), they don’t know what it's like not to be well; now yes, or at least [name of doctor] does; although it's more quality of life, like something more general, they explain that the treatments are to improve quality of life, you have to try to cut stress out of your life; you cry and when you stop crying, we talk |

| Lack of knowledge | |||

| Specialists | |||

| Variable approach | |||

| Needs detected | Psychological intervention | Usefulness | I went because I started having panic attacks in the underground (…) and they said I was immature; my illness didn’t start getting any better until I started going to the psychologist; my doctor says it would be very good, that it would do me good, but that there's no funding … To resolve problems or give quick support; six months later I was fine, and I even got a row for going |

| Speed | |||

| Social workers | Usefulness | For advice on legal issues, social resources and occupational disability | |

| Associations | Cover needs | [Many of these aspects] should be provided on the public health service |

The patients alluded to mood swings, which they partly related to their IBD, but they said they particularly faced serious social and occupational problems as a result of a lack of empathy for their problems. Differing views emerged on the subject of whether or not to inform the workplace about their illness because of the possible risk of dismissal or of not being taken on.

On the subject of how the specialists handle the psychological impact of IBD, patients made a distinction between those who see it as a matter of course and ask questions in the consultation and those who use some sort of test for the patient to answer separately. They agreed that the questions tend to be more focused on stress or quality of life and less on emotions, and that they find it difficult to have a free-flowing conversation.

All agreed on the need for quick and easy-to-access psychological intervention at critical points of the disease provided by empathic healthcare professionals with knowledge about IBD. They also all agreed on the need for access to social workers for advice on legal issues, social resources and occupational disability, and on the importance of patient associations, which cover many of these aspects.

All the above data show the influence psychological aspects have on the lives of people with IBD. Considering the importance of psychosocial aspects in the development and course of IBD, and in view of the fact that they may act as a trigger for clinical flare-ups,9 they should be considered as a treatment objective. It would therefore be of great help to have a psychologist in the multidisciplinary units.

The aim of the focus groups in this study was to identify specific aspects that might affect the lives of people with IBD that the project's scientific team had not detected, in order to enrich the survey. For the selection of the interviewees, an attempt was made to include the type of discourse that would produce the characteristics relevant to the research subject area. We therefore selected people greatly impacted by the disease. We felt that belonging to a patient association would not in itself interfere with the research subject area and might mean they were more likely to think about not only their own particular case, but about all patients in general, and more likely to have previously analysed the issue of the disease's impact.

Our study emphasises the need to assess psychosocial factors in patients with IBD, both in the emotional and occupational spheres, including how they are managed in the consultation and possible areas for improvement. This is the first step towards quantifying the impact of psychological aspects on IBD in a subsequent survey and identifying problems and needs in the management of these aspects in the specialist consultation, with the ultimate goal of correcting deficiencies.

FundingThe project received financial support from Merck Sharp & Dohme de España, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. (Kenilworth, NJ, United States of America).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the subject matter of the study. The ENMENTE project has the endorsement of ACCU España and Grupo Español para el Tratamiento de la Enfermedad de Crohn y la Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Group for the Treatment of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis].

Please cite this article as: Gobbo M, Carmona L, Panadero A, Cañas M, Modino Y, Romero C, et al. Impacto psicosocial y su manejo en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. El punto de vista de los pacientes. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:640–642.