Although eosinophilia is a condition that appears frequently in clinical practice, its prevalence in the general population in Spain is not well-defined.

ObjectiveTo determine the prevalence of eosinophilia in blood donors.

MethodologyDescriptive, cross-sectional study. Asymptomatic blood donors from the Haemotherapy and Blood Donation Centre of Castilla-León during January 2016 to December 2016 were included in the analysis.

Principal findingsOf a total of 63,941 donors, 8616 (13.5%) presented with eosinophilia, 3839 (44.6%) had relative eosinophilia, 4590 (53.3%) had mild eosinophilia, 185 (2.1%) had moderate eosinophilia and 2 (.02%) had severe eosinophilia. Of the donors with eosinophilia, 6401 (74.3%) were men. The mean of age (±SD) of was 41.4 years (±12.6); 8299 (13.5) were autochthonous, and 317 (13.0) were migrants. There were no significant differences in the presence of eosinophilia between immigrants and natives (p=0.47). Eosinophilia in the migrant cohort showed significant differences (p<0.005). Eosinophilia was higher among immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe (17.2%), followed by Latin America (14.8%), and North Africa (13.4%). The majority of blood donors did not take any medication related to eosinophilia, and none had any disease associated with eosinophilia.

ConclusionsEosinophilia is a frequent diagnosis in asymptomatic donors and it is not associated with being native-born or immigrant; however, in the migrant group there were differences according to the area of origin. The presence of eosinophilia was not associated with drugs or other obvious pathologies. A future prospective study must be performed in order to clarify the causes of eosinophilia in donors.

La eosinofilia es una alteración analítica frecuente en la práctica clínica. En la población general su prevalencia no está bien definida.

ObjetivoDeterminar la prevalencia de eosinofilia en donantes de sangre.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo, transversal. Se incluyeron donantes de sangre del Centro de Hemoterapia y Hemodonación de Castilla y León desde enero a diciembre de 2016.

ResultadosDe un total de 63.941 donantes, 8.616 (13,5%) presentaron eosinofilia; 3.839 (44,6%) tuvieron eosinofilia relativa, 4.590 (53,3%) tuvieron eosinofilia leve, 185 (2,1%) tuvieron eosinofilia moderada y 2 (0,02%) tuvieron eosinofilia grave. De los donantes con eosinofilia, 6.401 (74,3%) eran hombres. La media de edad (±DE) fue de 41,4 años (±12,6); 8.299 (13,5) eran autóctonas y 317 (13) eran migrantes. No hubo diferencias significativas respecto a la eosinofilia entre inmigrantes y nativos (p=0,47). Hay diferencias significativas en la eosinofilia entre los diferentes colectivos de inmigrantes (p<0,005). La eosinofilia fue mayor entre los inmigrantes de Europa Central y del Este (17,2%), seguida de lo originarios de América Latina (14,8%) y África del Norte (13,4%). La mayoría de los donantes de sangre no tomaron ningún medicamento relacionado con la eosinofilia, ni presentaban enfermedad asociada.

ConclusionesLa eosinofilia es un diagnóstico frecuente en donantes, no se asocia con ser autóctono o inmigrante. Entre inmigrantes hay diferencias según el origen. La presencia de eosinofilia no se asocia ni con fármacos ni con otras patologías. Se debería realizar en un futuro estudios prospectivos para aclarar las causas de la eosinofilia en donantes.

Eosinophilia is an analytical datum that represents an amount in the value of eosinophilic cells in tissues and/or in the blood.1 Eosinophilia can result from such mechanisms as clonal expansion, polyclonal expansion and tissue damage. The value of eosinophils that defines absolute eosinophilia is not well-defined. Some authors consider absolute eosinophilia when eosinophils are equal or more than 450×106eosinophils/L.2 The grade of eosinophilia is rarely helpful to identify the cause. Nevertheless, an extremely high count of eosinophils is predominantly associated with myeloproliferative disorders.3,4 Eosinophilia may appear frequently in the clinical practice thereby and been associated with different causes and cohorts5: (i) allergic-immune diseases (e.g., asthma, eosinophilic oesophagitis and others, etc.),6,7 (ii) drug reactions (e.g., drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms—DRESS-),8 (iii) connective tissue/rheumatologic diseases (e.g., eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, etc.),9 (iv) malignancies (most associated with haematological neoplasm, etc.),3,4 (v) parasitic and other infections (important in migrant and travellers from undeveloped areas),2,10–12 (vi) adrenal insufficiency,13 and (vii) others.5,14

Despite the fact that eosinophilia is characterized by frequent and classic analytical data,1,5 we have not found large epidemiological studies in healthy (asymptomatic) populations that establish the true prevalence of this entity in the general population, and the majority of studies have focused on a subgroup of diseases or cohorts with methodological problems too substantial to generalize results.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate eosinophilia in a population of blood donors collected for one year.

Material and methodsAn observational, cross-sectional and descriptive study was made. Blood donors at the Hemotherapy and Haemodonation Centre of Castilla-León from January 2016 to December 2016 were included. The medical records of the donors were evaluated according clinical protocols of Hemotherapy and Haemodonation Centre. Every patient with eosinophilia was remitted to general practitioner. The eosinophil count was performed using the Mindray BC-6800 an automated complete blood cell analyser. Relative eosinophilia was defined as an elevated eosinophil rate (>5%) in the absence of absolute eosinophilia (eosinophils <450×106eosinophils/L). Absolute eosinophilia was defined as >450×106eosinophils/L of blood. Mild eosinophilia was defined as >450×106eosinophils/L to 999×106eosinophils/L. Moderate eosinophilia was defined as >1000×106eosinophils/L to 2999×106eosinophils/L and severe eosinophilia was defined as >3000×106eosinophils/L.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were described using counts or frequencies (percentages). For analysis, such data are conveniently arranged in contingency tables that provide the frequencies for two or more categorical variables simultaneously (cross-tabulation of the counts). For the analysis of two-dimensional contingency tables, we used Pearson's χ2 test. It is the most commonly used test for the difference in distribution of categorical variables between two or more independent groups. Quantitative variables were expressed as means and standard deviation (±SD), range, median and interquartile range (IQR). To compare continuous variables, the Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test were used. Student's t-test investigates whether the expected values for two groups are the same, assuming that the data are normally distributed. In contrast, Mann–Whitney U test does not require the data to be normally distributed. Our dependent variables were eosinophil count (continuous variable) and categorized eosinophilia (categorical variable). Contrast of hypothesis was done with a 5% alpha risk and 95% confidence intervals. The SPSS 23.0® (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Ethical statementThis study involved the use of medical data from donors at the Hemotherapy and Blood Donors Centre of Castilla y León. All the data have been anonymized and identified with a code. According to the signed confidentiality compromise, none of the researchers have given any data to another research group. All the procedures described here were made according to the Helsinki declaration reviewed in 2013. The data provided were collected in a permanent file secured in the Hemotherapy and Blood Donor Centre of Castilla y León (Paseo Filipinos S/N, Valladolid, CP 47007, Spain). The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca (Salamanca, Spain).

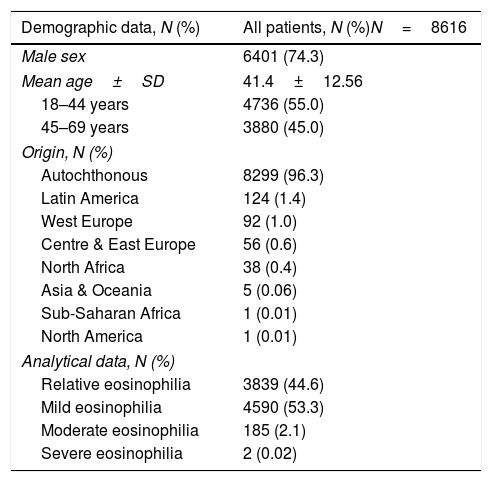

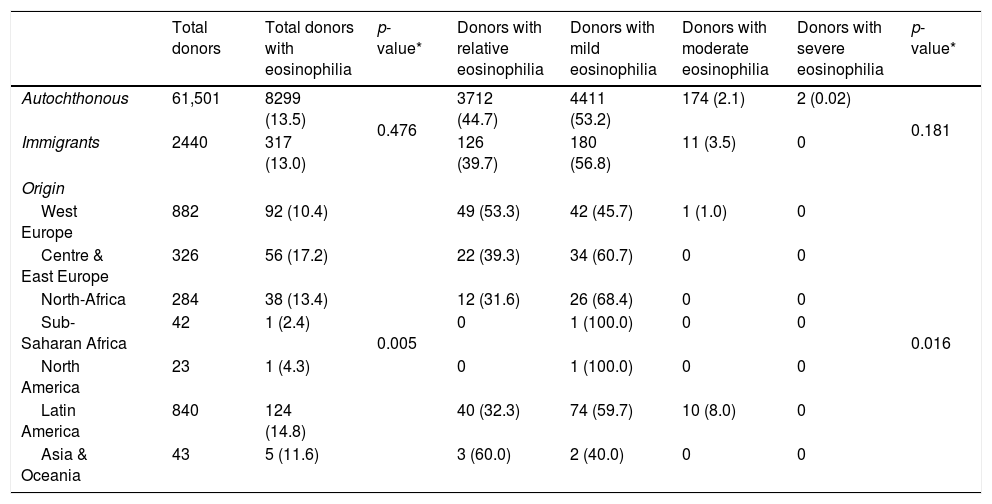

ResultsA total of 63,941 blood donors were evaluated. A total of 61,501 donors were Spanish/autochthonous, and 2440 were non-Spanish/migrants. 8616 donors (13.5%) had eosinophilia. Table 1 shows the primary epidemiological and analytical data of patient with eosinophilia. 3839 (44.6%) had relative eosinophilia, 4590 (53.3%) had mild eosinophilia, 185 (2.1%) had moderate eosinophilia and 2 (0.02%) had severe eosinophilia. 8299 were autochthonous, 317 were migrants. 6401 (74.3%) were male, with mean of age (±SD) of 41.4 years (±12.6) and median was 43 years [P25=32; P75=51]. No differences were observed between autochthonous and migrant donors with respect to global eosinophilia (p=0.476), or to categorized eosinophilia (p=0.181) as shown in Table 2. In both population groups, the majority were donors with mild eosinophilia (>450–999×106eosinophils/L), 53.2% in the native population and 56.8% in the migrant population.

Main data of the blood donors with eosinophilia.

| Demographic data, N (%) | All patients, N (%)N=8616 |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 6401 (74.3) |

| Mean age±SD | 41.4±12.56 |

| 18–44 years | 4736 (55.0) |

| 45–69 years | 3880 (45.0) |

| Origin, N (%) | |

| Autochthonous | 8299 (96.3) |

| Latin America | 124 (1.4) |

| West Europe | 92 (1.0) |

| Centre & East Europe | 56 (0.6) |

| North Africa | 38 (0.4) |

| Asia & Oceania | 5 (0.06) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 (0.01) |

| North America | 1 (0.01) |

| Analytical data, N (%) | |

| Relative eosinophilia | 3839 (44.6) |

| Mild eosinophilia | 4590 (53.3) |

| Moderate eosinophilia | 185 (2.1) |

| Severe eosinophilia | 2 (0.02) |

Data of the blood donors with eosinophilia by origin.

| Total donors | Total donors with eosinophilia | p-value* | Donors with relative eosinophilia | Donors with mild eosinophilia | Donors with moderate eosinophilia | Donors with severe eosinophilia | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autochthonous | 61,501 | 8299 (13.5) | 0.476 | 3712 (44.7) | 4411 (53.2) | 174 (2.1) | 2 (0.02) | 0.181 |

| Immigrants | 2440 | 317 (13.0) | 126 (39.7) | 180 (56.8) | 11 (3.5) | 0 | ||

| Origin | ||||||||

| West Europe | 882 | 92 (10.4) | 0.005 | 49 (53.3) | 42 (45.7) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0.016 |

| Centre & East Europe | 326 | 56 (17.2) | 22 (39.3) | 34 (60.7) | 0 | 0 | ||

| North-Africa | 284 | 38 (13.4) | 12 (31.6) | 26 (68.4) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 42 | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | ||

| North America | 23 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Latin America | 840 | 124 (14.8) | 40 (32.3) | 74 (59.7) | 10 (8.0) | 0 | ||

| Asia & Oceania | 43 | 5 (11.6) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 0 | ||

Nevertheless, there are significant differences (p=0.005) when we analyzed the data eosinophilia among different immigrant groups classified according to their origin. So, we can see in Table 2, eosinophilia was higher among immigrants coming from Central and Eastern Europe (17.2%) vs West Europe (10.4%), followed by Latin America (14.8%), North Africa (13.4%), and Asia & Oceania (11.6%). Most migrants are classified into categories relative eosinophilia and mild eosinophilia. There were also significant differences (p=0.016) between these two categories of eosinophilia and the origin of migrant donors. So, relative eosinophilia is more prevalent among immigrants coming from Central and Eastern Europe (53.3% vs 45.7%), while mild eosinophilia is more prevalent among immigrants coming from West Europe (60.7% vs 39.3%), North-Africa (68.4% vs 31.6), and Latin America (59.7% vs 32.3%) (Table 2).

The majority (296/317, 93.4%) of migrant blood donors had not taken any medication associated with eosinophilia in the last 3 months before the donation. The drugs that can produce eosinophilia are NSAIDs (9, 2.8%), ACE inhibitors (6, 1.9%), omeprazole (5, 1.6%) and doxycycline (1, 0.3%).

In the eosinophilia group, none had asthma, atopic/allergic symptoms or clinical data suggesting infectious diseases, immunological diseases or cancer associated with eosinophilia.

DiscussionThe relevance of eosinophilia has been established because it is associated with allergic and immunologic diseases, infectious disorders (most of them linked to parasitic diseases) and haematological diseases.

There are many factors that influence the number of eosinophils; therefore blood eosinophil counts have been reported to vary within the same person at different times of the day and on different days, both in individuals with eosinophilic disorders and in healthy volunteers. Nevertheless, the results are inconsistent among studies, and the variability in counts is rarely large enough to impact care.

Despite the fact that eosinophilia is a classical analytical datum, there are few studies that establish its prevalence in various pathologies.15–18 Therefore, the studies are not comparable. Possibly the cohort where many studies have been concentrated are migrants and travellers who come from tropical and subtropical areas endemic for parasitic infections, with an eosinophilic prevalence between 2.3% and 28.5%.2,10,11 Nevertheless, the majority of studies have been performed in tropical diseases and travel medicine units, which may represent a bias in these study designs.19–21 Therefore, in the absence of broad and solid epidemiological studies, it is usually suggested that in western countries, the most frequent causes are allergic diseases while in tropical regions they are parasitic infections.12

Our study showed similar eosinophilia figures (13.5% vs 13%) in the autochthonous cohort and the immigrant population. In our work, it should be noted that immigrants with a higher prevalence of eosinophilia were those from Central and Eastern Europe; in principle these results were not expected, due to the multitude of studies that reported high prevalence of eosinophilia imported from the sub-Saharan cohort, where prevalence can reach up to a third of cases.2,19,20,22 As explanations, we can argue that (i) eosinophilia has not been analyzed in the group of immigrants or travellers from Central and Eastern Europe11,23; (ii) possibly the sub-Saharan cohort analyzed is the one established in Spain in a stable and prolonged manner. It is less striking that the Latin American cohort has the highest figures of moderate eosinophilia.24,25

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and largest study to describe the situation of eosinophilia in the general and asymptomatic population; therefore, the results of our study show prevalence greater than 10% in asymptomatic and presumably healthy population, as is the group of donors. The scarce impact of drugs, allergies, and autoimmune and oncological diseases as possible causes of eosinophilia should be noted in this study, despite the fact that given the design of the study, we cannot rule out that some donors presented any of these entities in a sub-symptomatic manner.

The main limitations and biases of this study are attributable to several factors: (i) there was a retrospective design; (ii) blood eosinophil count data can be influenced by several factors such as circadian fluctuations, and there was only one blood sample26; (iii) we were not able to access the medical history that could allow us to confirm the findings or identify the possible diseases involved; and (iv) the study patients are probably not a representative sample of general population in Spain. For these reasons, the results should be interpreted with caution before extrapolation to the entire population.

In conclusion, we found a moderate prevalence of eosinophilia in asymptomatic donors that was not associated with being native-born or immigrant, but rather in the migrant group, there were differences according to the area of origin. A future prospective study must be done in order to clarify the causes of eosinophilia in donors.

FundingThis work was supported by the Health Research Projects: Technological Development Project in Health [Grant number DTS16/00207] and Health Research Project [Grant number PI16/01784] of funding institution Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the Network Biomedical Research on Tropical Diseases (RICET in Spanish)RD12/0018/0001, supported by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) from the European Commission. Moreover, financial regional/local support came from Proyectos Integrados IBSAL [IBY15/00003; Salamanca, Spain] and CIETUS-University of Salamanca.

Conflict of interestNone declared.