In this paper, we analysed In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) data from the registry of the Spanish Society of Fertility (SEF). This registry is not complete until 2014, when it started to be mandatory, as a part of the clinics did not report until that year. Also, information on patients is very limited. Our first purpose was to estimate the number of births obtained by IVF in Spain for the period 1999–2019, correcting for non-participation. In this sense, we stressed the importance of estimating the number of pregnancies with unknown evolution and the demand for IVF by non-resident women in the country, to arrive at a correct estimate of the weight of IVF in total births. We also discuss what kind of improvements could make this registry more useful, for the purposes of demographic and social analysis, but also to be able to better measure the effectiveness of these techniques. This paper shows the limits of having only aggregated data. In the near future, the SEF registry will become individual, and it is hoped that it can be even more useful in determining the impact of IVF and to what degree public demand is fulfilled.

Background and objectivesThe registry of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) in Spain is not complete until 2014. Here we reconstruct the series of cycles for the period 1999–2019 correcting for non-participation which allows us to estimate the weight of births from IVF in Spain, taking also into account pregnancies with unknown evolution as well as the demand of women residing abroad. We also discuss what kind of improvements could make this registry and the corresponding reports made by the Sociedad Española de Fertilidad (SEF) more useful, for the purposes of demographic and social analysis, in the light of the transition to an individual registry in upcoming years.

Materials and methodsWe use SEF reports on IVF and information on comparable registries for other countries and for Catalonia. We use also the Spanish Fertility Survey of 2018 to check the results of our estimates.

ResultsWe estimate that in year 2019 around 6.5% of births in Spain correspond to IVFs, very close to the figure for Denmark, the European country with the highest level. The proportion of deliveries lost to follow-up was high in the 2000s, over 20%, but lowered in the 2010s down to less than 10% and we estimate that in year 2019 around 35% of cycles were for women residing abroad. These estimates correlate well with what we observe from the Spanish Fertility Survey of 2018.

ConclusionsUsing data on IVF in Spain for demographic analysis is harder than it should be, which forces to conduct a very thorough analysis of the reports and to make guess estimates in order to obtain useful results. Also, the aggregate nature of the registry considerably limits the analysis. We hope that the individual register which will start hopefully in 2022 or 2023 will help in improving the quality of the research on factors and characteristics of IVF in Spain.

En este trabajo se analizan los datos de Fecundación In Vitro (FIV) del registro de la Sociedad Española de Fertilidad (SEF). Este registro no está completo hasta 2014, año en que empezó a ser obligatorio, ya que una parte de las clínicas no informaron hasta ese año. Además, la información sobre los pacientes es muy limitada. Nuestro primer propósito fue estimar el número de nacimientos obtenidos por FIV en España para el periodo 1999-2019, corrigiendo por la no participación. En este sentido, destacamos la importancia de estimar el número de embarazos de evolución desconocida y la demanda de FIV por parte de mujeres no residentes en el país, para llegar a una estimación correcta del peso de la FIV en el total de nacimientos. También se discute qué tipo de mejoras podrían hacer más útil este registro, a efectos de análisis demográfico y social, pero también para poder medir mejor la eficacia de estas técnicas. Este documento muestra los límites de tener sólo datos agregados. En un futuro próximo el registro SEF será individual, y se espera que pueda ser aún más útil para determinar el impacto de la FIV y hasta qué punto se satisface la demanda pública.

Antecedentes y objetivosEl registro de Fecundación In Vitro (FIV) en España no está completo hasta 2014. Aquí reconstruimos la serie de ciclos para el periodo 1999-2019 corrigiendo por la no participación lo que nos permite estimar el peso de los nacimientos por FIV en España, teniendo en cuenta también los embarazos de evolución desconocida así como la demanda de las mujeres residentes en el extranjero. También se discute qué tipo de mejoras podrían hacer más útil este registro y los correspondientes informes realizados por la Sociedad Española de Fertilidad (SEF), a efectos de análisis demográfico y social, de cara a la transición a un registro individual en los próximos años.

Material y métodosUtilizamos los informes de la SEF sobre FIV y la información de los registros comparables de otros países y de Cataluña. Utilizamos también la Encuesta Española de Fecundidad de 2018 para comprobar los resultados de nuestras estimaciones.

ResultadosEstimamos que en el año 2019 alrededor del 6,5% de los nacimientos en España corresponden a FIV, muy cerca de la cifra de Dinamarca, el país europeo con el nivel más alto. La proporción de partos perdidos en el seguimiento fue alta en la década de 2000, más del 20%, pero bajó en la década de 2010 hasta menos del 10% y estimamos que en el año 2019 alrededor del 35% de los ciclos fueron de mujeres residentes en el extranjero. Estas estimaciones se correlacionan bien con lo que observamos en la Encuesta Española de Fecundidad de 2018.

ConclusionesUtilizar los datos de FIV en España para el análisis demográfico es más difícil de lo que debería, lo que obliga a realizar un análisis muy exhaustivo de los informes y a realizar estimaciones conjeturales para obtener resultados útiles. Además, el carácter agregado del registro limita considerablemente el análisis. Esperamos que el registro individual que se pondrá en marcha previsiblemente en 2022 o 2023 ayude a mejorar la calidad de la investigación sobre los factores y características de la FIV en España.

The use of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) in Spain has grown at a very fast rate over the last three decades where it has a notably higher impact than in most other developed countries. Thus, in 2015 Spain was for the first time the European country where most IVF cycles were carried out, position it maintained in 2016, but lost to Russia in 2017 (according to yearly reports of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, or ESHRE, on Assisted Reproductive Techniques, or ART). Moreover, as we will show, the proportion of total births obtained by IVF was in 2017 more than three times higher in Spain than in France and the United States (according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC), and comparable to Denmark, the European country with the highest level registered.

In Spain, the first factor that explains this strong demand is the considerable delay in the age of first motherhood, which reached 31 years in 2018, and leads more than 40% of women of childbearing age to reach 35 years childless, at an age after which the probability of having a birth begins to drop significantly. South Korea has the highest age at first birth in the world at 31.9 years in 2018, the lowest fertility level of 0.98 children per woman this year (Statistics Korea, 2019), and is also one of the countries with the highest proportion of IVF births, with 5.8% of all births in 2017 due only to IVF births funded by state programmes (Kim, 2019). However, fertility postponement is not the only determinant, since in Italy, a country with a similar age at first childbearing than Spain, the proportion of births due to IVF was less than half the level of Spain in 2014. Other factors, such as the legal and social framework, and above all the subsidies of the health system, seem to play an important role (Kocourkova et al., 2014; Präg and Mills, 2017b) to explain the strong demand for assisted reproduction in countries like Denmark, where coverage is universal for women under 40, or like Israel, where IVF is free up to 45 years of age (Birenbaum-Carmeli, 2016). Indeed, IVF with own eggs is fully subsidized in Spain for women under 40 years of age, with or without a partner, for up to three cycles and the 2006 law on Assisted Reproduction has very few restrictions, as only surrogacy is banned (Calhaz-Jorge et al., 2020).

In this context it is important to study the evolution of IVF in Spain, because it is the European country with the most important business activity in this sector, and because Spanish centers are those that respond to most of the European demand for IVF with donor eggs. In this work, we found out to what extent the information collected in the IVF registry, carried out by the Spanish Society of Fertility (SEF), is useful for social analysis, what limitations it has in this regard and how these could be improved in the future. Specifically, we want to study in this paper the effect of IVF on the birth rate. This led us to discuss in detail the degree of coverage of the registry and the quality of the data obtained. We will see that, in order to measure this effect, it is necessary to make corrections, due to shortcomings specific to the Spanish registry, but often common to all equivalent registries and which are not always known or recognized by analysts. Another important related point, but which we did not address in this study, is the difference between what we could call the medical doctor’s point of view and that of the demographer: the former is interested in knowing how many births begin with an assisted reproduction treatment, while for the latter the interest is in determining the number of births that would not have occurred without the use of this technique, since some women would have had them naturally with a little more patience. In this study, and for simplicity, we will use the doctor's point of view, that is to say to count all the births due to IVF (the demographer's point of view is assumed for example by Leridon (2004).

Material and methodsIn this work, we mainly used data from the Spanish registry reports for the years 1999–2019, available on the SEF website (and accompanied each year by a publication, the last being: Cuevas et al., 2020), which we complemented with data from the IVF registry of the Spanish region of Catalonia (the last report published corresponds to the data for the year 2014, and unfortunately the registry was abandoned afterwards). We have also used data from the reports of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) which is the European counterpart of the SEF. ESHRE centralizes data from European registries, including those of the SEF. We completed this data with information from the Belgian (Belgian Registry for Assisted Procreation - Belrap), Danish (Danish Fertility Service - DFS), Russian (Russian Association of Human Reproduction - RAHR) and United States (Center for Disease Control and Prevention - CDC) registries (see the references in the data section at the end).

National IVF registries vary in nature, with some being mandatory and others being voluntary. Many are of an aggregate type, but some are also based on individual data, which explains in part the differences in their results and quality of coverage (De Geyter et al., 2019), what we discuss below. Concerning the Spanish registry, we analyzed in this paper the evolution: of its degree of coverage, of the number of cycles initiated and of the effects of IVF on the birth rate. This leads us to discuss factors usually not taken into account by ESHRE in their reports, like the under registry of births by IVF due to the incomplete follow-up of deliveries, or the existence of the "cross border reproductive care", when patients prefer to travel abroad to get access to IVF, factors whose weight is highly variables across countries.

The registry of In Vitro Fertilization in SpainSince 1993, the SEF has published annual reports containing the data on IVF carried out in Spain. These reports have improved notably with time, both in detail and exhaustiveness, and they incorporate data on Intra-Uterine Insemination (IUI) from 1999 onwards. From the beginning reporting was voluntary, and until 2005 less than half of the centers authorized by the Ministry of Health participated. Coverage increase afterwards and reached 92% of the authorized clinics in 2015, while the remaining 8% probably had no activity this year. Participation is compulsory, starting with treatments carried on in 2014, as the SEF registry had become the official one at the national level, and therefore the coverage of IVF, as well as of IUI, can be considered exhaustive from year 2015, as in year 2014 the data of some of the last centers to join was not included due to a lack of compliance. This registry is thus focused on IVF and IUI, and does not provide any data on other treatments like timed intercourse with ovarian stimulation (TI), for which there is very little information in Spain, when it is a common treatment in other countries (Jones, 2003; Schieve et al., 2009), while it is covered in the Belgian reports on "non-IVF" technique. In fact there is a consensus on the point that only IVF should be considered as Assisted Reproductive Techniques (ART), when both IUI and TI should be included in the wider category of Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR) treatments: Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2017).

Another notable limitation is that information about patients is very scarce, as the approach is generally more clinical than social. Thus, the data analysed are "cycles" of IVF initiated, and the total number of patients for most treatments is not even known. As a result, it is not possible to determine exactly from the information in this registry what proportion of women have received assisted reproduction treatment, be it IVF, IUI and even less TI, nor what proportion manage to have children with the use of these techniques, because there is no follow-up of patients from cycle to cycle, unlike again, in the Belgian registry. Sociodemographic information is also very poor, age information is always provided in five-years age groups, and there is no direct indication of coverage by the public health system. Although the SEF reports include a breakdown of the numbers of IVF centers by region and public or private status, no information is given on the proportion of treatments conducted in public hospitals. However, Castilla et al. (2009) were able to estimate the weight of public coverage in the 2002–2004 period using the unpublished IVF data provided by clinics, which are later aggregated in the SEF reports: approximately 25% of the IVF were carried out by the public system in that period, and more than 95% of the egg donation took place in private clinics.

The situation in Spain contrasts with other countries, where registration is complete and information on women is more detailed. For example, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom have had a complete registry of IVF since at least 1997. Moreover, in these countries it is often possible to link the individual data in the IVF registry with other administrative and demographic sources, which makes it possible to take into account the social and medical context of the patients (as an example, see Jensen et al. 2008).

Since its inception, this registry has been compiled from information provided in an aggregate manner by each center: each one prepares tables in a common format that it then communicates to the SEF for its annual report. The compulsory registry carried out in the Spanish region of Catalonia by FIVCAT (Bosser et al., 2009) started almost at the same time, and the collection was exhaustive. At the beginning it followed the same procedure of compiling aggregate tables for each center, but from 2001 onwards, the information was of an individual nature, and each center was connected to a common database, in a telematic way (for a comparison of the two registries, see Luceño et al., 2010). As mentioned above, it seems that the Catalan registry is no longer being carried out at present. The reason why is that an individualized and centralized registry of IVF is being implemented at the Spanish level, which would play a double role with the Catalan registry, although this will not be fully operational until year 2022 or 2023.

The procedure for collecting and analysing data by the SEF is longitudinal: each treatment that begins throughout the year is attempted to be followed to its end, for example, from egg collection to delivery. Therefore, the births included in each annual report refer to a period that includes the last months of the current year plus the first 9 months of the following year. This explains why reports on IVF cycles are usually published 2 years later, and why a not insignificant proportion of pregnancies have unknown results, if the center that initiated the IVF cannot follow the patient until delivery. In contrast, the exploitation of the Catalan registry at the beginning was of a cross-sectional type, as described in their publications. This means that all the data collected belong to the same year, and therefore most of the births included in the annual report do not correspond to the IVF or IUI recorded for the same year. This considerably biases certain estimates, due to the strong growth in assisted reproduction, especially at the beginning of the 2000's. It is only as of 2009 that the FIVCAT reports also include a longitudinal type of exploitation like that used by the SEF, i.e., with the follow-up of each treatment until birth. However, these reports provide more complete and useful information on the patients than the Spanish one.

Evolution of the number of clinics in SpainSupplemental Figure I displays the evolution of the number of clinics that were authorized by the Ministry of Health to carry out IVF treatments, as well as those that voluntarily participated in the collection of data by the SEF. In general terms, the number of authorized centers remained relatively stable from 2000 to 2010 and increased steadily thereafter. Nonetheless this number decreased slightly in the years 2009 and 2010, and again in 2012 and 2013, although we do not know if this is due to the general economic situation or to an update of the data of the registry of centers by the Ministry, although the former is more likely.

Until 2013, the proportion of registered clinics reporting IVF-related activity was relatively low and gradually increased from approximately 30–60%. This proportion decreased in 2008, when the SEF proposed to publish detailed results of the centers, which led to the temporary withdrawal of some of them (de la Fuente and Requena, 2011). This publication was finally made in a very limited way, and the comparison of results between centers was ruled out, contrary to what is done, for example, by the US registry, which provides data on the effectiveness of the activity of each center. There is a significant jump in this proportion in years 2014 and 2015, during which more than 90% of the registered clinics reported IVF cycles to the SEF, and probably the rest did not have any activity. This is due to the legal obligation for centers to report their ART treatments, beginning with the 2014 registry, although the registry is complete only starting in 2015.

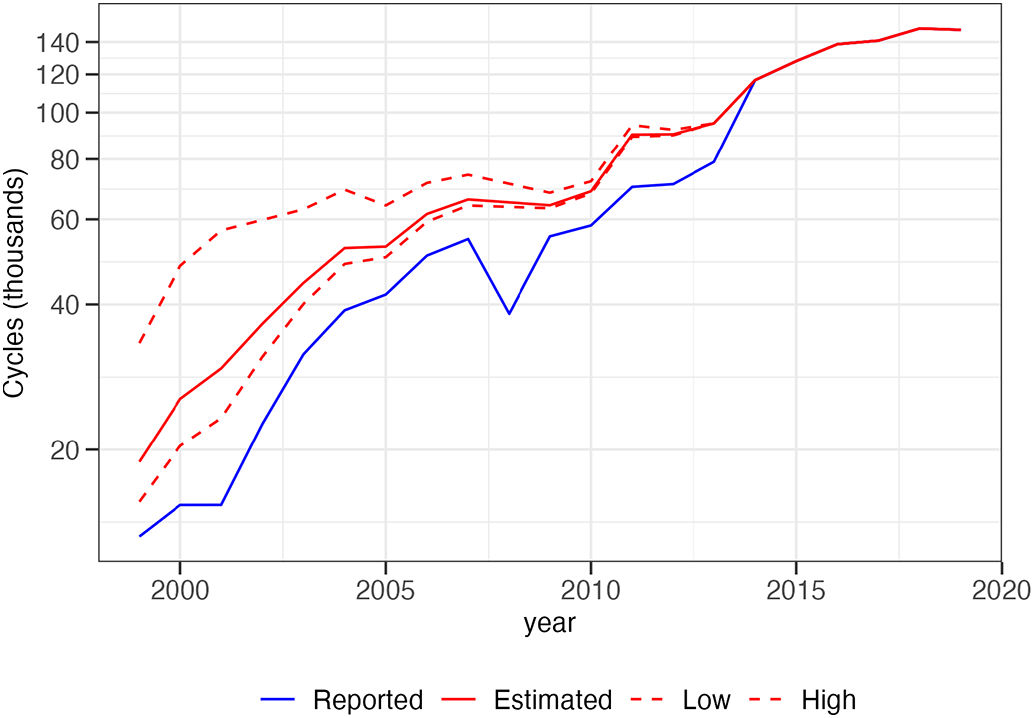

Number of cyclesFig. 1 presents data on the number of cycles initiated by all types of IVF registered by the SEF and corrected to consider that only a part of the clinics reported. A sustained increase is observed throughout the period, with a smaller increase in the years 2008–2010, probably again due to the economic crisis. During the period observed, the number of cycles increased by a factor of 8, with a faster growth until 2004, at an annual rate of 20%, which then slowed down, with an annual rate of 8% between 2004 and 2019.

Evolution of the number of IVF cycles initiated in the year indicated and corrected for non-participation, 1999–2019.

Data derived from SEF reports. Logarithmic scale for the cycles. The estimated series is derived from the reported number of cycles with a correction for non-reporting of a significant proportion of centers (the relative size of clinics that do not report, compared to those that inform, varies linearly between 24% in 1999 and 45% in 2013). The dashed line curves are alternative estimates for judging of the sensitivity of the correction procedure: the lower-level curve corresponds to the hypothesis that clinics not reporting performed in year 1999 an average number of cycles equal to 10% of the number of those reporting, and the higher-level curve to a relative level in year 1999 of 86%, with a linear variation up to year 2013 with the same relative size of 45% than the main hypothesis.

The correction applied consists of trying to estimate the number of cycles performed by the clinics that did not report to the SEF, even if they have been active. One of the criterions we followed consisted of obtaining annual numbers of cycles in Spain such that the trend in time and the level of the proportion resulting from IVF births of resident women are similar to those observed for Catalonia, where the data in the registry are in principle exhaustive since at least 1999. We also rely on the evolution of the proportion of clinics participating in the registry. Thus, for example, based on the values for the years 2013 and 2014, when the greatest jump in this proportion occurred (from 64% to 92% of registered centers), we estimated that the clinics that began to report in 2014 carried out 45% of the average number of treatments of those that already reported in 2013.

To arrive at that estimate, we hypothesized that the two types of centers, those that reported to the SEF in the initial year and those that reported as of the final year, grew at the same rate in the period, equal to 8%, which is the approximate annual growth rate of the number of cycles in that period. To estimate the relative size of the centers that did not report at year t, we used the formula:

Where St1 is the mean number of cycles reported by the centers in year t, obtained dividing the number of cycles Ct by the number of centers Nt; St2 is the size in year t of the centers which started reporting in year t+1, estimated by [Ct+1/(1 + 0.08) − Ct]/(Nt+1 − Nt). Observe that in this way we project the mean size of centers which started to report in year t+1 back to year t.The hypothesis that we consider the most likely to reconstruct the evolution of the relative size of the IVF centers that did not report to the SEF is constructed by setting its initial value in 1999 at 24% of the size of the centers that reported. We assume that this relative size then grows in a linear fashion between 1999 and 2013, to reach the previous value of 45%.

In order to judge the sensitivity of this hypothesis, we use a set of two other initial values of this relative size, one low of 10% and one high of 86%, which provides us with two alternative series of the number of cycles, represented in Fig. 1 by the dashed line curves. For year 2008, in which there was an abrupt fall in the number of cycles recorded due to the refusal of some centers to participate, we estimated the number of cycles based on an exponential interpolation between the years 2007 and 2009.

Deliveries lost to follow-upThe registration of IVFs is mainly based on the monitoring of transfers of in vitro fertilized embryos to check whether they implant, i.e., give rise to a pregnancy. The time window of this follow-up is short, from 1 to 2 months. The quality of this information is usually much better than that concerning births, because women very often have their delivery in another center, especially if they are residents of another country or region. This explains why the proportion of IVF pregnancies with unknown subsequent development is important, as shown in Supplemental Figure III, with data for Spain and other countries. This proportion was particularly high in Spain, where it exceeded 30% during the 2000s, as well as, but to a lesser extent, in Russia, while it remained below 10% in Catalonia and Belgium and was negligible in the USA. A possible explanation for this difference is that the Spanish and the Russian registries were voluntary at that time, when it was mandatory in the three other countries. In this sense, it can be noted that the proportion of births lost to follow-up has decreased considerably in Spain since the register became exhaustive, and is now at the level of the Belgian register.

The problem this poses is that IVF deliveries and births will necessarily be underestimated, insofar as approximately 80% of these pregnancies with unknown evolution correspond to deliveries and births not counted by the IVF registry (the rest corresponding to spontaneous abortions and stillbirths). It is therefore necessary to take account of this defect in the records when attempting to estimate the number of births due to IVF, and especially in international comparisons, which is not done, for example, in the ESHRE publications.

In this regard, it is important to note that estimating this proportion of "lost" births is not always easy and cannot be limited to what is directly reported by the registry but must be based on a thorough check. For example, in the case of Spain, we estimated that 36% of IVF pregnancies had an unknown evolution during 2007, when the registry only recognized a loss of 5%. Supplemental Table I gives details of why this discrepancy exists, in the case of IVF cycles using fresh own eggs, which represented most treatments this year. This table shows that the annual report started with a count of all cycles, Ct, but then limited itself to the "complete" cycles, Cc, for which there was information on all phases up to delivery. Therefore, the pregnancy and delivery figures in the report did not include those for "incomplete" cycles. The report then provided two pregnancy figures, the total Pt, and those for which the results of a clinical follow-up were declared, Pc. Therefore, we have a second level of underestimation, which corresponds to pregnancies without the result of this monitoring. For these "clinical" pregnancies, information was provided about the number A of abortions and corresponding deliveries D, as well as of the "unknowns" U, which are the pregnancies without further information. But the sum of these three figures is not equal to the total number of clinical pregnancies, so there were 1,845 cases without information of any kind (that corresponds to the term N in the following formula). If we combine the four sources of underestimation of the number of births, we go from the reported figure of 5,161 to an estimate of 7,714 births per IVF with own fresh eggs, which is 49.5% higher than the number of reported births, and therefore a proportion of "lost" births equals to 33%.

As detailed in Supplemental Table I, we arrive at this value of 1.495 as a total multiplier of deliveries reported in the registry, which is the product of the 4 multipliers corresponding to each case of underestimation of the real number in the 2007 SEF report, as follows:

Where L is the multiplier of births reported by the registry and D* is the estimated total number of deliveries.This estimate assumes that the probability of a pregnancy is the same for “complete” and “incomplete” cycles, and that pregnancies without declared clinical follow-up or those with unknown outcomes are as likely to end in delivery as pregnancies with clinical follow-up up to delivery. Note also that, if the above assumptions are valid, the proportion of “missed” births will be equal to the proportion of pregnancies lost to follow-up, which is the standard way of presenting that information.

Differences between regionsThe map in Supplemental Figure II compares IVF activity by region in Spain, presenting the number of cycles carried out, divided by the number of women aged 15–49, based on data for the year 2017, during which registration was exhaustive. It is observed that there is a great disparity in the territory, with a much higher frequency in the Valencian Community, Catalonia, Madrid, the Basque Country or La Rioja. This is probably explained by the effect of population density and economic level. In fact, clinics are preferably located in large cities and in those with the highest standard of living, since a large part of the IVFs carried out are not covered by the public health system.

But another important factor that explains these differences at a territorial level is the demand from women not resident in Spain, whose effects must be bigger in the regions with a better connection to foreign countries. These women generally move to Spain because the laws on assisted reproduction are more restrictive in other countries, especially for women without a male partner or for women who need an egg donation (Präg and Mills, 2017a).

Estimating the proportion of patients residing abroadThe SEF publishes very little data on the origin or characteristics of patients undergoing IVF treatments, and these data do not appear to be accurate. Thus, the first information relating to the number of cycles for non-resident women appears in the 2014 report, from which it can be deduced that overall, 9,966 IVF cycles were reported for non-resident women out of a total of 116,688. But these data do not coincide at all with those collected in Catalonia by FIVCAT, where the report for 2014 indicated that IVF patients coming from abroad represented 48% of the total number of treatments in Catalan clinics, which would correspond to approximately 13,700 cycles, i.e., much more for this region alone than the previous figure at the national level. Therefore, the proportion of non-resident patients treated in Spain is certainly much higher than indicated by the SEF, probably closer to that observed in Catalonia, especially in regions where the impact of IVF is similar, such as the Valencian region, Madrid and the Basque Country. Supplemental Figure V shows that, on the other hand, the proportion of women living abroad and treated in Catalan clinics has increased considerably since 2001 and by 2014 these patients represented half of the demand for these medical treatments, a considerably higher proportion than in two other European countries with a long tradition of receiving foreign patients, Belgium and Denmark.

To reconstruct the weight of the demand for IVF in Spain by non-residents, we proceed in two steps. First, we use regional data provided by the SEF registry for the period 2014–2019, when this registry was exhaustive. We base our estimates for this period on the assumption that the demand for IVF of Spanish residents was similar to the one observed in Catalonia in that period. For example (see Supplemental Table II), in year 2014, the demand of IVF in Catalonia by non-residents (from abroad or another Spanish region) was of half the total, which also means that the number of IVF cycles corresponding to women residing in Catalonia was 8.25 per 1000 women of fertile age. If we suppose that the demand of residents was the same in the rest of Spain (with small adjustments for less developed regions like Extremadura or the Canary Islands), we can compute by difference for each region the amount of IVF cycles that are likely to correspond to women residing abroad or in another region. Let us take the case of the Region of Valencia: in year 2014 the number of IVF cycles per 1000 women was of 16.3, from which we subtract the value of 8.25 corresponding to the demand of women resident in Catalonia, which gives us a figure of 8.05 cycles per thousand which should correspond to non-resident women. Conversely, the clinics in the Castilla-La Mancha region carried out 3.4 IVF cycles per thousand and the difference with the theoretical demand, corresponding to the Catalan level, is negative, at 4.85 per thousand. In this case, we assumed that some women from this region have moved to another region for their IVF treatment. We can then add up the excess or deficit of IVF cycles carried on by clinics in each region, which gives the total number corresponding to women living abroad, which this year represented 26.8% of the total cycles in Spain. The same calculation can then be made for the years 2015 to 2019.

The second step of this estimation procedure corresponds to the period 1999–2013 for which the SEF registry is incomplete. We start by observing that about two-thirds of the demand by women residing abroad correspond to IVF cycles with donor eggs (according to the SEF reports for the period 2014–2019). Actually, the proportion of IVF treatments with donor oocytes or embryos is considerably higher in Spain and Catalonia than in the rest of Europe (Supplemental Figure IV), which is most probably a consequence of the high demand from abroad. In fact, it can be seen that in Catalonia there is a strong correspondence between the two curves for the proportion of IVF with eggs donation and for the proportion of demand from women residing abroad (comparing Supplemental Figures IV and V). These two observations form the basis of our procedure for estimating foreign demand in Spain before year 2014. First, we computed a fixed coefficient for year 2014 between the proportion of IVF cycles from women residing abroad as estimated before for Spain, and the proportion of IVF from donors’ eggs, using it for estimating a series for the period 1999–2013 for the foreign demand of ART, by multiplying it each year by the proportion of IVF with egg donation. We also derived another similar series using the same coefficient, but varying each year, using similar Catalan IVFs data, multiplying these varying coefficients with the proportion of IVF with egg donation for Spain in the period 1999–2013. The final estimate for the series of the proportion of the demand of IVF by women residing abroad is then obtained by a weighting average of the preceding two estimated series, giving precedence to the series with the fixed coefficient for Spain in the last years of the 1999–2013 period and to the series with the varying coefficients for Catalonia at the start of this period.

Impact of IVF on the birth rate in SpainThe cycle figures obtained above are the basis for estimating the number of births per IVF that resident women had and is used to compute its weight in the total births for Spain. These births due to IVF from women residing in Spain are estimated as follows, for each year:

To obtain Bt*, the estimated number of births per IVF of resident women for year t, we start from BtReg, the number of live births obtained by IVF as reported annually in the national registry. We apply a multiplier to consider the non-participation of the centers, dividing Ct*, the number of IVF cycles estimated previously, by CtReg, the number of cycles reported. This number of births is then increased by multiplying it by a factor of births lost to follow-up, Lt, as calculated above. At this point, we have the total number of births by IVF performed in Spanish clinics, to which we apply the proportion Rt of IVF patients residing in the country, to obtain the number of births of Spanish women started with these treatments.

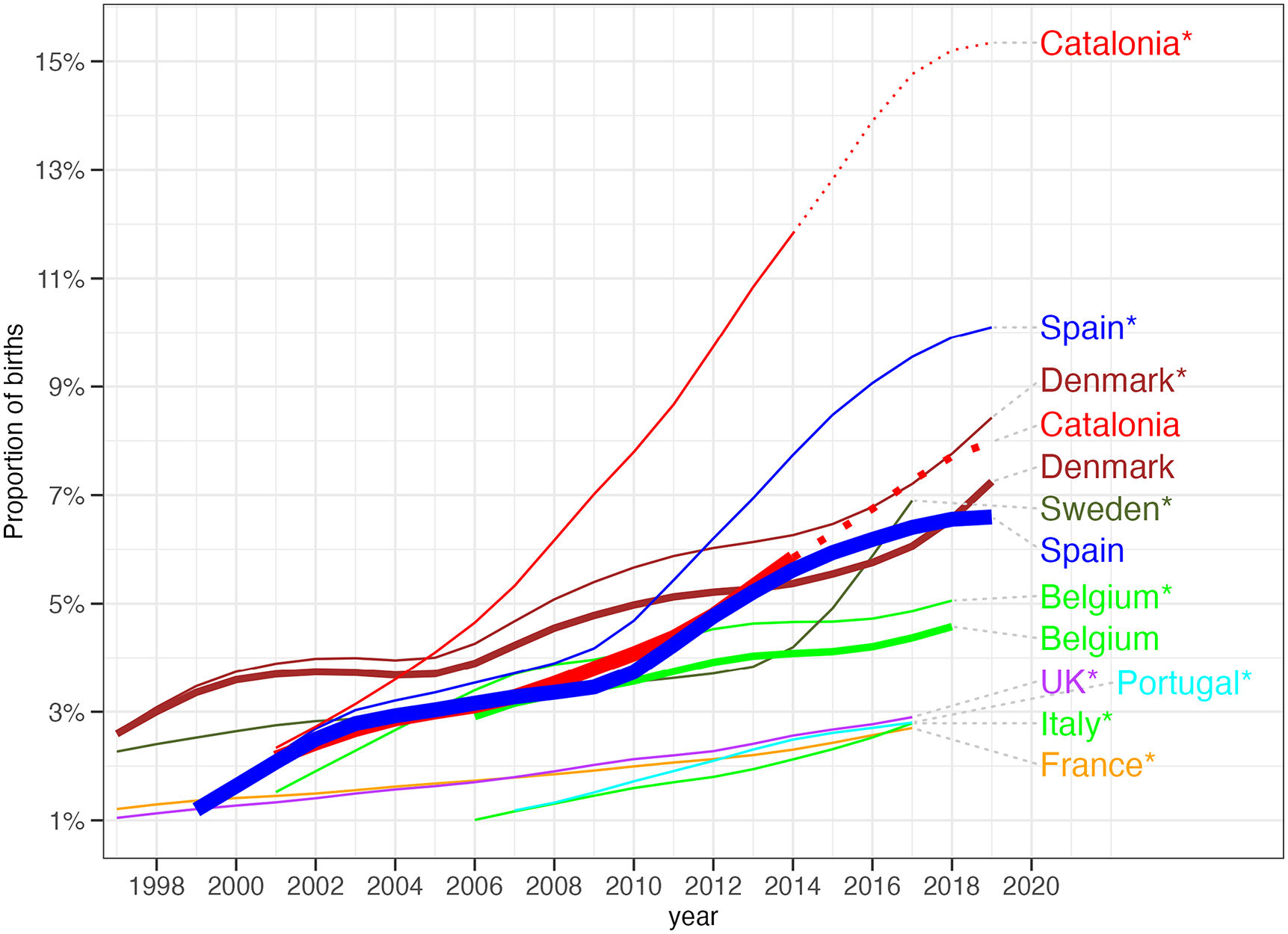

Fig. 2 presents the weight of births from IVF in the total for Spain and Catalonia, comparing with other European countries. The series are of two types: calculated from the total number of births as reported by the national IVF registries (and in this case we add an asterisk after the name of the country in the graph) and series corrected to take into account the double effect, which operates in the opposite direction, of "lost" births and of the demand for IVF by women residing abroad.

Proportion of total births from IVF in Spain and Catalonia compared with other European countries, 1999–2019, with and without corrections for non-resident demand and deliveries lost to follow-up.

Data derived from the Spanish, Catalan, Belgian and Danish registries as well as ESHRE reports for the other countries. The series with the names of the countries followed by an asterisk correspond to the total IVF births as reported by the national registries (for Spain, with our correction for clinics which didn’t report). The series for Belgium, Catalonia, Denmark and Spain plotted with thick lines correspond to births corrected to exclude non-residents women and to include births corresponding to pregnancies lost to follow-up, as explained in the text (the reports from the Danish registry do not allow us to estimate the proportion of "lost" births and therefore we have not applied the corresponding correction for this country). The series for Catalonia are extrapolated for the period 2015–2019 based on the IVF cycles numbers for this region published by the SEF, equalling the numbers for both series for year 2014. Series smoothed using Tukey’s 4253H smoother (Velleman, 1980).

As can be seen from this chart, it is essential to consider the weight of demand for IVF by non-residents in countries where it is significant, such as Belgium, Denmark, Spain and especially Catalonia. Thus, in Denmark IVF births in 2018 represented 8.2% of the total, but when we exclude non-residents, what is not done in ESHRE reports, the figure is down to 6.5%. The situation is more extreme in Catalonia in 2019: we estimate that births which started from an IVF in a Catalan center represent more than 15% of the total births, but of those only 7.5% corresponds to IVF births from women who live in that region. Conversely, for countries such as France, Germany or Italy, it would be interesting to have data on patients who had to go to another country for assisted reproduction treatments, in order to have a correct estimate of the effect of IVF on their birth rate.

If we now look at the weight of IVF, net of external demand, we see that in recent years it has grown considerably in Spain, to levels higher than Belgium and close to those of Denmark, which in the last two decades has been the European country with the greatest contribution of IVF to the birth rate. But it is also remarkable to note that, in the region of Catalonia, the demographic impact of IVF is even greater than in Denmark, with a similar total population.

Using the Spanish Fertility Survey of year 2018 to assess the accuracy of the resultsThe estimate of the number of births from the IVF register for Spain is therefore the result of three successive approximations, which correct defects of this register. Fortunately, an independent source, the Spanish Fertility Survey 2018, makes it possible to verify the goodness of the results. This survey contains questions on the use of assisted reproduction, and specifically on gestations initiated by IVF, which makes it possible to calculate the weight of this technique in the series of births reconstructed with this survey. Supplemental Figure VI shows the proportion of births in Spain started with an IVF after applying the three corrections detailed above, as well as the proportion as reconstructed with the Fertility Survey of 2018, both compared with the proportion computed from the “official” numbers as reported by the SEF and the ESHRE, here corrected from non-participation by some centers.1 We observe that the series derived from the Spanish Survey is closer to our corrected series in recent years than the “official” one, which seems to validate our estimate than in recent years around 30 % of births initiated from an IVF treatment in Spanish clinics were from women residing abroad.

Suggested improvements to the IVF register and SEF reportsUntil now, the Spanish IVF register carried out by the SEF was of an aggregate type, which explains many of the shortcomings of the published reports discussed in this paper. These reports were essentially aimed at assisted reproduction professionals, which explains their focus on cycle accounting, leaving patients in a secondary position. Information on the techniques used was privileged to the detriment of other characteristics of interest, publishing for example data on cycles with innovative techniques such as 'preimplantation genetic diagnosis' without always detailing the origin of the eggs (own or donor, fresh or cryopreserved).

In the near future, this register will become individual, which could improve the annual reports, and opens up the possibility of statistical analysis, especially if the micro-data are made available to external researchers, as would be desirable and is done, for example, in the United Kingdom. It is hoped that the improvement in the register will also lead to a restructuring of the SEF reports. In this sense, it would be desirable that these have results on the follow-up of patients, and not only on IVF cycles, for example, to compute cumulative pregnancy or delivery rates. It would also be useful for both analysts and the public if the data were published mainly on the basis of four categories only: own or donor eggs, and for each group, cryopreservation or fresh transfer. More detailed data on the different techniques should be included in a second level of disaggregation only.

But the main advance that will allow individual-type information for analysts will be to be able to have data by simple age, and not just by large age groups as is the case now. In this sense it would be interesting to have the age of the woman treated with an IVF at the time of the transfer, but also at the time of the collection of the eggs, especially in the case that they are not her own or that there has been cryopreservation. Individual information on the patients must allow them to be monitored from cycle to cycle in order to estimate the probability of success or the time needed to obtain a live birth. This obviously requires that each patient has a unique identifier, but it is important that it could be used to link to other administrative records, which is the case for example for the IVF register in Denmark. In this respect, there is a great need for more and reliable information on patients, for example, their geographical origin (outside the region, living abroad), their family and social context, and also whether they have paid for treatment or whether it is covered by social security or a mutual fund. If this information is not directly collected in the new individual register, it could be obtained with a link to other public ones.

Current SEF reports also provide very little information about men, and it is hoped that the individual register will make it possible to know in the future whether IVF is carried out with the partner's sperm or with sperm from a donor. It would also be of interest to know more about the proportion of patients who would certainly or most probably not have had a pregnancy without IVF treatments. The only data published by the SEF refers to the "indications" for IVF treatment. In 2016, the "female factor" represented only 28.5% of these, which would seem to indicate that 71.5% of patients would have been able to have a pregnancy naturally, which is surprising. To go into details and to be able to study better the factors of success of IVF, it would be very useful, apart from counting on the age of the woman throughout the process, from the puncture to the pregnancy, to systematically collect data on the day of the embryo transfer (e.g., if the blastocyst stage has been reached), on the voluntary multifetal reduction, or on the quality of the embryos. Finally, it would be very useful for patients and analysts to be able to compare the results between clinics, as the US reports of the CDC allow. This is a point of conflict, as was seen in Spain in 2008, and can be deduced from the fact that no European country yet publishes data of this type.

National reports on ART used:Spain: Informes de la Sociedad Española de Fertilidad, years 1999–2019: https://www.registrosef.com/index.aspx#Anteriores.

Catalonia: FIVCAT.NET: estadística de la reproducció humana assistida a Catalunya, years 2001–2014: https://scientiasalut.gencat.cat/handle/11351/987.

Russia: Art register reports of the Russian Asociation of Human Reproduction (in Russian), years 2002–2017: https://www.rahr.ru/registr_otchet.php.

Belgium: Assisted Reproductive Technology National Summary Reports, years 1999–2018 https://www.belrap.be/Public/Reports.aspx.

Denmark: The Danish National Register of assisted reproductive technology (in Danish), years 2000–2019: https://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/registre-og-services/om-de-nationale-sundhedsregistre/graviditet-foedsler-og-boern/ivf-registeret.

USA: Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART), years 2001–2017: https://www.cdc.gov/art/artdata/index.html.

United Kingdom: Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, years 2001–2017: https://www.hfea.gov.uk/about-us/publications/research-and-data/

Other European countries: yearly ESHRE reports. The last one consulted is: ART in Europe, 2017: results generated from European registries by ESHRE, years 2001–2017: https://www.eshre.eu/Data-collection-and-research/Consortia/EIM/Publications.aspx

Observe that we have shifted 0.75 years forward in time the two series obtained from the SEF registry to take into account that it follows cycles initiated in a calendar year and the resultant births occur 9 months later.