To analyse the occupational safety measures used by clinical embryologists and their relationship with conditions in the workplace.

MethodsAn online questionnaire was designed to gather demographic and occupational information, together with safety and ergonomics in the workplace and was sent to all the embryologists that are members of the Association for the Study of Biology of Reproduction (ASEBIR).

ResultsIt was found that 11.2% of embryologists never wear gloves when handling semen, and 19.6% never wore them while working with follicular fluid. In addition, 30% rarely or never use protection when working with liquid nitrogen. Between 23.3% and 47.5% believe their working conditions are not comfortable. Logistic regression analysis showed that embryologists working in small laboratories (fewer than five people) and those who considered ventilation to be inadequate are less likely to wear gloves while handling follicular fluid. On the other hand, those with less than ten years of experience and those who considered the laboratory ventilation to be inadequate are less likely to wear gloves while working with liquid nitrogen. Embryologists working in large laboratories receive more training in safety in the workplace.

ConclusionThe results of this study indicate that the provision of workplace safety measures in embryology laboratories is related to perceptions of risk, the characteristics of the work, the level of embryologist experience, the size of the laboratory, and the working conditions.

Analizar las medidas de seguridad laboral utilizadas por los embriólogos clínicos y su relación con las condiciones de trabajo.

MétodosSe envió un cuestionario online sobre cuestiones demográficas y ocupacionales, así como seguridad y ergonomía en el lugar de trabajo, a todos los embriólogos miembros de ASEBIR.

ResultadosSe encontró que el 11,2% de los embriólogos nunca usa guantes al manipular semen, y el 19,6% tampoco lo hace cuando trabaja con líquido folicular. Además, el 30% usa rara vez o nunca protección cuando trabaja con nitrógeno líquido. Entre el 23,3% y el 47,5% creen que sus condiciones de trabajo no son cómodas. El análisis de regresión logística mostró que los embriólogos que trabajan en laboratorios pequeños (menos de cinco personas) y los que consideran que la ventilación es inadecuada, son menos propensos a usar guantes cuando manipulan líquido folicular. Por otra parte, los embriólogos con experiencia inferior a diez años y los que considera la ventilación del laboratorio inadecuada, son menos propensos a usar guantes mientras trabajan con nitrógeno líquido. Embriólogos que trabajan en grandes laboratorios reciben más formación en materia de seguridad laboral.

ConclusiónLos resultados de este estudio indican que la utilización de medidas de seguridad en los laboratorios de embriología se relaciona con la percepción del riesgo y grado de experiencia de los embriólogos, y con las características del trabajo, tamaño del laboratorio y condiciones laborales.

Clinical embryologists are exposed to biological hazards (infectious diseases) and physical ones (liquid nitrogen and sharp instruments) in their daily laboratory work, and significant numbers of accidents in the workplace have been reported (Tomlinson, 2008).

To minimise fatigue and distraction, it is important to be aware of recent developments in equipment and facilities, ergonomics (bench height, adjustable chairs, microscope eye height, etc.), the efficient use of space and surfaces and appropriate air quality and light conditions, with controlled humidity and temperature. It is also fundamental to ensure that appropriate numbers of staff are present, with the necessary experience to address the laboratory workload and the techniques required (Magli et al., 2008).

Policies related to occupational safety should be adopted and proper training given in preventive measures and efficient risk management (Mortimer and Mortimer, 2004). The correct application of safety measures in the embryology laboratory has been related with individual characteristics, such as experience (Tomlinson and Morroll, 2008). However, the application of safety measures does not always facilitate performance of the tasks involved, and are sometimes found uncomfortable or rejected by the workers. For example, the use of gloves in the embryology laboratory has been associated with low rates of embryonic development (Nijs et al., 2009).

In this study, we analyse the adoption of security measures by clinical embryologists and its relation with the conditions in which they work.≤

Materials and methodsStudy designSecondary study of a cross-sectional design to conduct an online self-assessment survey.

ParticipantsThe study population included in the present study, consisted of all the embryologists who are members of the Spanish Association of Clinical Embryologists (Asociación para el Estudio de la Biología de la Reproducción; ASEBIR) who had been working during the previous nine months. In 2013, two e-mails were sent to all ASEBIR members explaining the aims of the research. At the time of the survey, ASEBIR had a total of 787 members (212 male and 575 female; 26.9–73.1%), of whom 184 (23.4%) were working in public laboratories (data obtained from the ASEBIR secretariat). The e-mails sent contained a link to the online questionnaire and consent form. Google Drive was used as an online platform for the questionnaires. To estimate the true value of the proportion of accidents in the last year with a precision of 4%, at a 95% confidence level and assuming a prevalence of 25% (Fritzsche et al., 2012), a study population of 230 persons was required. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital (Granada).

MeasurementsSociodemographic and occupational characteristicsThe subjects were first asked to complete a series of questions related to sociodemographic issues, including age, gender, the existence of a stable relationship and the number of children. Secondly, the questionnaire inquired about occupational characteristics and workload: the position held as embryologist during the last nine months (yes/no), type of centre (public/private), number of hours worked per week, length of service (<10 years/≥10 years), contract duration (permanent/temporary), contract type (full time/part time) and number of staff employed in the laboratory.

To evaluate procedures for safety in the workplace, questions were asked about the use of gloves during the manipulation of semen and follicular fluid, and the use of measures for physical protection during the manipulation of liquid nitrogen. Responses to these items were rated on a six-point Likert scale ranging from “Always” to “Never”. Questions were also asked about whether the laboratory personnel were vaccinated against hepatitis B virus and flu virus, and whether the laboratory had supplied training on hazard awareness and on laboratory safety rules (yes/no).

Job-related conditions were assessed with five questions (yes/no) on ergonomic conditions in the workplace, focusing on comfort, illumination, temperature, noise and ventilation. Finally, the respondents were asked if they had suffered any kind of accident in the workplace during the previous two years. “Accident” was defined as an incident requiring more than simple first aid treatment (Hofmann and Stetzer, 1996).

Statistical analysesWe report the univariate statistics for the use of gloves during the manipulation of semen and of follicular liquid, the protection used when handling liquid nitrogen, and the training given on safety in the workplace. The chi-square test was used to compare the results for the different groups. Three multivariable linear regression models were built for the three principal variables: the use of gloves for the manipulation of follicular liquid, the existence of protection when handling liquid nitrogen, and training on safety in the workplace.

ResultsParticipantsAfter two reminders had been sent out, the final response rate was 34.7% (254/731). Ten questionnaires were excluded because the respondents had not worked during the previous nine months, and another four were excluded because the respondents had answered fewer than 50% of the survey questions. Thus, 240 valid questionnaires were finally computed.

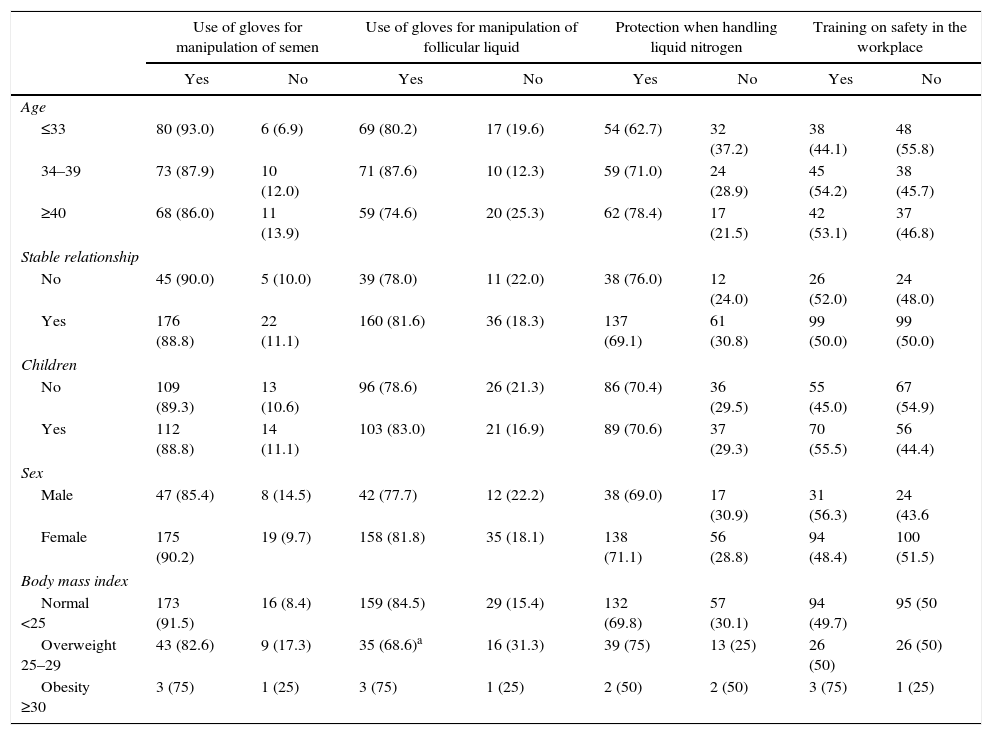

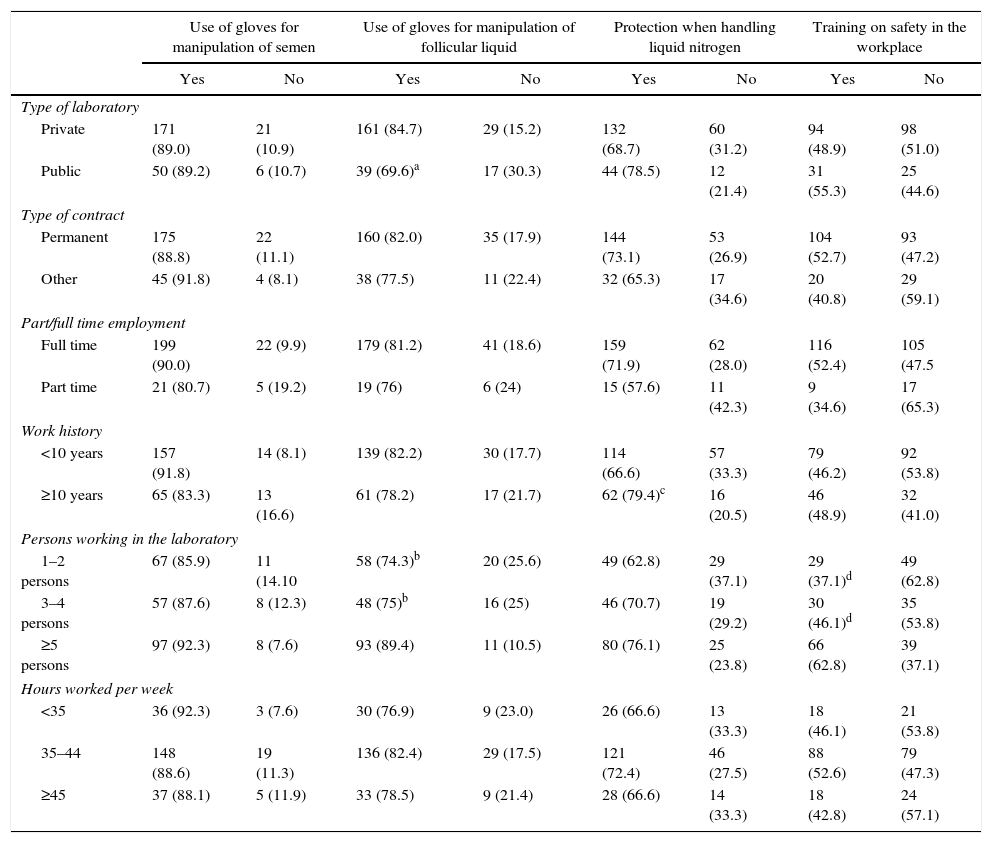

With respect to safety in the workplace, over 11.2% of the embryologists never wore gloves when manipulating semen and 19.6% never wore them while working with follicular fluid. Furthermore, and alarmingly, almost 30% never or only occasionally took protective measures when handling liquid nitrogen. 10% were not vaccinated against hepatitis B virus and 90% were not vaccinated against flu. 42% of the embryologists had not received training on the occupational safety measures applicable in their workplace (Tables 1–3). Only six accidents were reported, all related to accidental puncture with a sharp object. No injuries were caused by handling liquid nitrogen.

Prevalence of the use of gloves and of training on workplace safety, stratified by sociodemographic variable.

| Use of gloves for manipulation of semen | Use of gloves for manipulation of follicular liquid | Protection when handling liquid nitrogen | Training on safety in the workplace | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤33 | 80 (93.0) | 6 (6.9) | 69 (80.2) | 17 (19.6) | 54 (62.7) | 32 (37.2) | 38 (44.1) | 48 (55.8) |

| 34–39 | 73 (87.9) | 10 (12.0) | 71 (87.6) | 10 (12.3) | 59 (71.0) | 24 (28.9) | 45 (54.2) | 38 (45.7) |

| ≥40 | 68 (86.0) | 11 (13.9) | 59 (74.6) | 20 (25.3) | 62 (78.4) | 17 (21.5) | 42 (53.1) | 37 (46.8) |

| Stable relationship | ||||||||

| No | 45 (90.0) | 5 (10.0) | 39 (78.0) | 11 (22.0) | 38 (76.0) | 12 (24.0) | 26 (52.0) | 24 (48.0) |

| Yes | 176 (88.8) | 22 (11.1) | 160 (81.6) | 36 (18.3) | 137 (69.1) | 61 (30.8) | 99 (50.0) | 99 (50.0) |

| Children | ||||||||

| No | 109 (89.3) | 13 (10.6) | 96 (78.6) | 26 (21.3) | 86 (70.4) | 36 (29.5) | 55 (45.0) | 67 (54.9) |

| Yes | 112 (88.8) | 14 (11.1) | 103 (83.0) | 21 (16.9) | 89 (70.6) | 37 (29.3) | 70 (55.5) | 56 (44.4) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 47 (85.4) | 8 (14.5) | 42 (77.7) | 12 (22.2) | 38 (69.0) | 17 (30.9) | 31 (56.3) | 24 (43.6 |

| Female | 175 (90.2) | 19 (9.7) | 158 (81.8) | 35 (18.1) | 138 (71.1) | 56 (28.8) | 94 (48.4) | 100 (51.5) |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| Normal <25 | 173 (91.5) | 16 (8.4) | 159 (84.5) | 29 (15.4) | 132 (69.8) | 57 (30.1) | 94 (49.7) | 95 (50 |

| Overweight 25–29 | 43 (82.6) | 9 (17.3) | 35 (68.6)a | 16 (31.3) | 39 (75) | 13 (25) | 26 (50) | 26 (50) |

| Obesity ≥30 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages.

Prevalence of the use of gloves and of training on workplace safety, stratified by occupational variable.

| Use of gloves for manipulation of semen | Use of gloves for manipulation of follicular liquid | Protection when handling liquid nitrogen | Training on safety in the workplace | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Type of laboratory | ||||||||

| Private | 171 (89.0) | 21 (10.9) | 161 (84.7) | 29 (15.2) | 132 (68.7) | 60 (31.2) | 94 (48.9) | 98 (51.0) |

| Public | 50 (89.2) | 6 (10.7) | 39 (69.6)a | 17 (30.3) | 44 (78.5) | 12 (21.4) | 31 (55.3) | 25 (44.6) |

| Type of contract | ||||||||

| Permanent | 175 (88.8) | 22 (11.1) | 160 (82.0) | 35 (17.9) | 144 (73.1) | 53 (26.9) | 104 (52.7) | 93 (47.2) |

| Other | 45 (91.8) | 4 (8.1) | 38 (77.5) | 11 (22.4) | 32 (65.3) | 17 (34.6) | 20 (40.8) | 29 (59.1) |

| Part/full time employment | ||||||||

| Full time | 199 (90.0) | 22 (9.9) | 179 (81.2) | 41 (18.6) | 159 (71.9) | 62 (28.0) | 116 (52.4) | 105 (47.5 |

| Part time | 21 (80.7) | 5 (19.2) | 19 (76) | 6 (24) | 15 (57.6) | 11 (42.3) | 9 (34.6) | 17 (65.3) |

| Work history | ||||||||

| <10 years | 157 (91.8) | 14 (8.1) | 139 (82.2) | 30 (17.7) | 114 (66.6) | 57 (33.3) | 79 (46.2) | 92 (53.8) |

| ≥10 years | 65 (83.3) | 13 (16.6) | 61 (78.2) | 17 (21.7) | 62 (79.4)c | 16 (20.5) | 46 (48.9) | 32 (41.0) |

| Persons working in the laboratory | ||||||||

| 1–2 persons | 67 (85.9) | 11 (14.10 | 58 (74.3)b | 20 (25.6) | 49 (62.8) | 29 (37.1) | 29 (37.1)d | 49 (62.8) |

| 3–4 persons | 57 (87.6) | 8 (12.3) | 48 (75)b | 16 (25) | 46 (70.7) | 19 (29.2) | 30 (46.1)d | 35 (53.8) |

| ≥5 persons | 97 (92.3) | 8 (7.6) | 93 (89.4) | 11 (10.5) | 80 (76.1) | 25 (23.8) | 66 (62.8) | 39 (37.1) |

| Hours worked per week | ||||||||

| <35 | 36 (92.3) | 3 (7.6) | 30 (76.9) | 9 (23.0) | 26 (66.6) | 13 (33.3) | 18 (46.1) | 21 (53.8) |

| 35–44 | 148 (88.6) | 19 (11.3) | 136 (82.4) | 29 (17.5) | 121 (72.4) | 46 (27.5) | 88 (52.6) | 79 (47.3) |

| ≥45 | 37 (88.1) | 5 (11.9) | 33 (78.5) | 9 (21.4) | 28 (66.6) | 14 (33.3) | 18 (42.8) | 24 (57.1) |

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages.

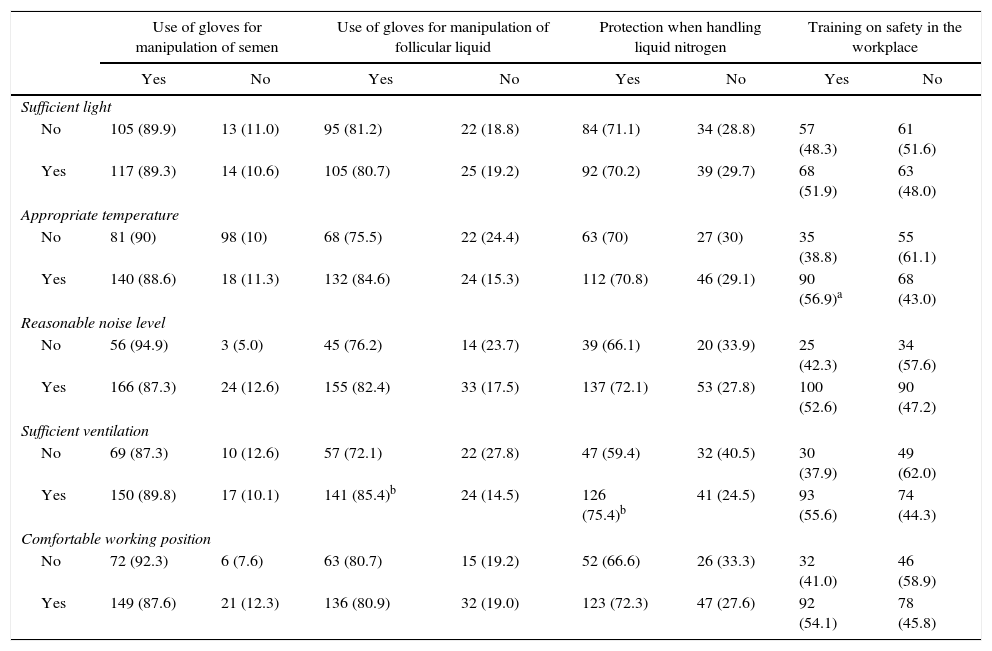

Prevalence of the use of gloves and of training on workplace safety, stratified by ergonomic variable.

| Use of gloves for manipulation of semen | Use of gloves for manipulation of follicular liquid | Protection when handling liquid nitrogen | Training on safety in the workplace | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Sufficient light | ||||||||

| No | 105 (89.9) | 13 (11.0) | 95 (81.2) | 22 (18.8) | 84 (71.1) | 34 (28.8) | 57 (48.3) | 61 (51.6) |

| Yes | 117 (89.3) | 14 (10.6) | 105 (80.7) | 25 (19.2) | 92 (70.2) | 39 (29.7) | 68 (51.9) | 63 (48.0) |

| Appropriate temperature | ||||||||

| No | 81 (90) | 98 (10) | 68 (75.5) | 22 (24.4) | 63 (70) | 27 (30) | 35 (38.8) | 55 (61.1) |

| Yes | 140 (88.6) | 18 (11.3) | 132 (84.6) | 24 (15.3) | 112 (70.8) | 46 (29.1) | 90 (56.9)a | 68 (43.0) |

| Reasonable noise level | ||||||||

| No | 56 (94.9) | 3 (5.0) | 45 (76.2) | 14 (23.7) | 39 (66.1) | 20 (33.9) | 25 (42.3) | 34 (57.6) |

| Yes | 166 (87.3) | 24 (12.6) | 155 (82.4) | 33 (17.5) | 137 (72.1) | 53 (27.8) | 100 (52.6) | 90 (47.2) |

| Sufficient ventilation | ||||||||

| No | 69 (87.3) | 10 (12.6) | 57 (72.1) | 22 (27.8) | 47 (59.4) | 32 (40.5) | 30 (37.9) | 49 (62.0) |

| Yes | 150 (89.8) | 17 (10.1) | 141 (85.4)b | 24 (14.5) | 126 (75.4)b | 41 (24.5) | 93 (55.6) | 74 (44.3) |

| Comfortable working position | ||||||||

| No | 72 (92.3) | 6 (7.6) | 63 (80.7) | 15 (19.2) | 52 (66.6) | 26 (33.3) | 32 (41.0) | 46 (58.9) |

| Yes | 149 (87.6) | 21 (12.3) | 136 (80.9) | 32 (19.0) | 123 (72.3) | 47 (27.6) | 92 (54.1) | 78 (45.8) |

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages.

Regarding working conditions, between 23.3% and 47.5% of respondents believed their workplace was not comfortable (31.4%), was insufficiently lit (47.5%), was at an inappropriate temperature (36.2%), was too noisy (23.3%) or was poorly ventilated (32.1%). Logistic regression analysis on the use of gloves for semen manipulation did not highlight any significant explanatory factor, although these embryologists were significantly less likely to wear gloves when manipulating follicular fluid when they worked in small laboratories (<5 persons) (OR: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.16–0.85) and when they considered the ventilation in the workplace was inadequate (OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.23–0.95). The frequency of use of protection against liquid nitrogen was significantly lower in the group of embryologists who had less than ten years’ laboratory experience (OR: 0.49, 95% CI 0.25–0.94) and among those who believed the laboratory ventilation was inadequate (OR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.25–0.82). Training in risk prevention and safety measures at work was more rigorous for embryologists working in laboratories with more than five technicians (OR: 3.38, 95% CI: 1.75–6.52) and who worked in a laboratory where the temperature was appropriate (OR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.20–3.97).

DiscussionIn Spain, flu vaccination is recommended for all healthcare workers, in the view that they may transmit the disease to people at high risk. Nevertheless, according to the present study, only 10% of Spanish embryologists are vaccinated against flu. This low level of vaccination is similar to that observed in other healthcare workers (Jimenez-Garcia et al., 2007; Llupià et al., 2012), and may be due to a lack of awareness that the recommendations made by the Ministry of Health are motivated not by the embryologists’ own vulnerability but to prevent them from becoming transmitting agents (Maltezou and Tsakris, 2011). Accordingly, such recommendations should be heeded, especially by embryologists working in centres with paediatric activity. Because the lack of time represents a major barrier to vaccination, laboratory managers should consider dedicating time specifically to vaccination, in order to improve coverage among embryologists (Jimenez-Garcia et al., 2007).

However, when the vaccine is mandatory, as is the case for hepatitis B, the rate of compliance is high (90%), exceeding that observed for other healthcare workers (Loulergue et al., 2009), which is consistent with the findings of other studies of laboratory personnel (Fritzsche et al., 2012; Mir et al., 2012).

Operator protection against infectious body fluid contamination is a safety issue in assisted reproduction techniques (ART) laboratories (Magli et al., 2008; Tomlinson et al., 2012). However, gloves have a “bad reputation” among embryologists, as is confirmed by our high percentage of embryologists who never or only occasionally use gloves when manipulating follicular fluid. One reason for this could be that when using gloves in the ART laboratory, toxic substances can be transmitted to culture media. Indeed, in ART, this is the consumable that most frequently presents reprotoxic effects (Lierman et al., 2007; Nijs et al., 2009). Nevertheless, this “bad reputation” in itself is not sufficient to account for the results obtained, because the differences observed in the use of gloves when manipulating semen or follicular liquid suggest that the factor of perceived risks should also be taken into account. Thus, embryologists seem to perceive greater risks in the handling of semen than in that of follicular fluid, and so they are more likely to wear gloves in the first of these cases. Several authors have concluded that the extent to which workers perceive the work itself as dangerous is a key factor in compliance with safety measures (Storeth, 2007; Snyder et al., 2008). This increased perception of risk when handling semen may explain why none of the variables analysed (sociodemographic, occupational or ergonomic) was significantly associated with the use of gloves when manipulating the semen.

The larger the team of embryologists employed in the laboratory, the more likely they are to wear gloves when handling follicular fluid, and to receive safety training. This finding confirms that another factor in safety compliance is the extent to which workers perceive that their coworkers provide them with safety-related cooperation and encouragement (Hayes et al., 1998; Siu et al., 2003). Embryologists working alone or with few companions feel less encouraged to follow safety rules or are less motivated to be trained in safety measures.

The perceived quality of procedures and occupational conditions is a key factor regarding safety in the workplace (Christian et al., 2009). Our results show that embryologists who perceive their working conditions to be poor (for example, as concerns inadequate ventilation) are less likely to wear gloves for handling follicular fluid and liquid nitrogen. Thus, improving working conditions is an essential complement to the implementation of policies aimed at enhancing safety in the workplace (Neal and Griffin, 2006).

Our results confirm the findings of Tomlinson and Morroll (2008) about the greater awareness of the risks involved in handling liquid nitrogen among senior embryologists, with respect to their junior colleagues. As suggested by these authors, senior embryologists can play a fundamental role in workplace safety training by advising their less experienced colleagues of potential hazards and by highlighting appropriate measures to avoid them. The possible loss of sensitivity and dexterity should also be taken into account as a factor accounting for embryologists’ failure to use gloves when handling liquid nitrogen (Tomlinson, 2008).

The percentage of embryologists who had not received training in safety in the workplace (42%) was similar to that obtained in a survey of embryologists in the UK (Tomlinson and Morroll, 2008). Safety knowledge, as reported by Griffin and Neal (2000) and highlighted in our own results, is a direct determinant of safety performance (for example, ensuring the existence of good working conditions in order to reduce the risks of accidents). Furthermore, we observed a direct relation between safety training and adequate temperature in the workplace.

Despite the low percentage of embryologists who had received safety training, the percentage of accidents suffered at work in the last two years (6.2%) was lower than that reported by other clinical laboratory staff (Shoaei et al., 2012; Fritzsche et al., 2012). This could be due to the potentially severe consequences of errors in the embryology laboratory, which encourage staff to be especially meticulous, thus reducing the frequency of accidents. Safety outcomes (accidents) are more strongly associated with group and organisational safety than with psychological safety (the individual perspective) (Christian et al., 2009). For example, an embryologist with low safety awareness might be more likely to accidentally spill liquid nitrogen (accident), but would be no more likely to be injured by such a spill, provided the laboratory required the use of protective clothing.

Among the limitations of this study is the fact that because only six accidents were reported, no significant association could be established between these accidents and the study variables. In addition, this low number may be due to the fact that accident data are self reported, and so a reporting bias may be present (Burke et al., 2002).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that self-protective behaviour by the embryologist in the workplace is related to the risks perceived, the occupational conditions in the laboratory and the individual's experience. These characteristics should be taken into account when developing intervention programmes to enhance safety in the workplace for embryologists.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that for this investigation have not been performed experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that this article does not appear patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this article does not appear patient data

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the ASEBIR executive committee and the staff of the ASEBIR secretariat. We also thank all the ASEBIR members for their cooperation.

This article is related to the Ph.D. Doctoral thesis by B. López-Lería.