Biofilm formation by Bacillus cereus strains is now recognized as a systematic contamination mechanism in foods; the aim of this study was to evaluate the production of submerged and interface biofilms in strains of B. cereus group in different materials, the effect of dextrose, motility, the presence of genes related to biofilms and the enterotoxigenic profile of the strains. We determine biofilm production by safranin assay, motility on semi-solid medium, toxin gene profiling and genes related to biofilm production by PCR in B. cereus group isolated from food. In this study, we observe strains used a higher production of biofilms in PVC; in the BHI broth, no submerged biofilms were found compared to phenol red broth and phenol red broth supplemented with dextrose; no strains with the ces gene were found, the enterotoxin profile was the most common the profile that includes genes for the three enterotoxins. We observed a different distribution of tasA and sipW with the origin of isolation of the strain, being more frequent in the strains isolated from eggshell. The production and type of biofilms are differential according to the type of material and culture medium used.

La formación de biopelículas por cepas de Bacillus cereus es reconocida como un mecanismo de contaminación sistemática en alimentos; el objetivo del estudio fue evaluar la producción de biopelículas sumergidas y de superficie en cepas del grupo de Bacillus cereus en diferentes materiales, el efecto de la dextrosa, la motilidad, la presencia de genes relacionados a biopelículas y el perfil enterotoxigénico de las cepas. Determinamos la producción de biopelículas por el ensayo de safranina, motilidad en medio sólido, perfil enterotoxigénico y genes relacionados a producción de biopelículas por PCR en aislados del grupo de Bacillus cereus de alimentos. En este estudio, observamos en las cepas utilizadas una alta producción de biopelículas en PVC; en caldo BHI, no se encontraron biopelículas sumergidas en comparación con el caldo rojo de fenol y caldo rojo de fenol suplementando con dextrosa; no se encontraron cepas con el gen ces, el perfil de enterotoxinas más común fue el perfil que incluía los genes de las tres enterotoxinas, también observamos una distribución diferente de tasA y sipW con relación al origen de la cepa, siendo más frecuente estos genes en las cepas aisladas de huevos. La producción y el tipo de biopelículas es diferente de acuerdo con el tipo de material y el medio de cultivo utilizado.

Bacillus cereus is a Gram positive microorganism, widely distributed in the environment, capable of causing food poisoning due to the consumption of contaminated food, which is caused by the production of emetic toxin (encoded by the ces operon) in food16 or from diarrheagenic toxins (HBL, NHE, and CYTK) in the small intestine when spores are germinated by the pH of the intestinal lumen7,22,34,35.

The formation of endospores has been described as one of the main mechanisms associated with the ubiquity of the B. cereus, and its presence throughout the food production chain. These endospores are resistant to various physical and chemical agents14, as well as their adhesion characteristics18,19,48. However, biofilm formation by B. cereus strains is also now recognized as a systematic contamination mechanism50 and has been described in food industries, including milk, sugary drinks, and ice cream23,37,46. This biofilm formation has been described in the case of B. cereus in product storage tanks or pipes36. Also, the formation of two biofilms stands out on the interface of the stored liquids (air-interface liquid) and submerged (solid–liquid interface)50. Because the food production environment has infrastructure and equipment made of different materials, the formation of biofilms of B. cereus has been studied in different hydrophobic or hydrophilic materials5,25,33, as well as in different culture media1,33 and the participation of different trace elements in the formation of biofilms24,29, even the relationship with the origin of isolation of the strain has been sought5,25,31. Ultimately, genes related to biofilm production have been investigated and found as homologs in B. subtilis9,11, a microorganism in which biofilm production has been extensively studied, in addition to the possible participation of flagellum during the process28. Therefore, the objective of this work was to evaluate the production of submerged and interface biofilms, the effect of dextrose on motility and biofilm production, the presence of genes related to biofilms, and the enterotoxigenic profile of strains of B. cereus group from different foods in different materials

Materials and methodsStudy groupThe study included 43 strains biochemically identified as Bacillus cereus group according to ISO 7932:2004. The strains belonged to the biobank of the Laboratorio de Patometabolismo Microbiano of Universidad Autonoma de Guerrero and were isolated from previous studies. All the strains were isolated in southern Mexico, on metallic surfaces and food distributed throughout the country (powered infant formula, infant food, and eggshell). The B. cereus ATCC 14579 strain was used as a positive control strain for molecular identification of B. cereus, toxin gene profiling (hbl+), motility, and genes related to biofilm production. To control of amplification of nhe and cytK genes, a strain of B. cereus BC372 previously characterized in the laboratory was used. B. cereus BC372 was originally isolated from adobero cheese2.

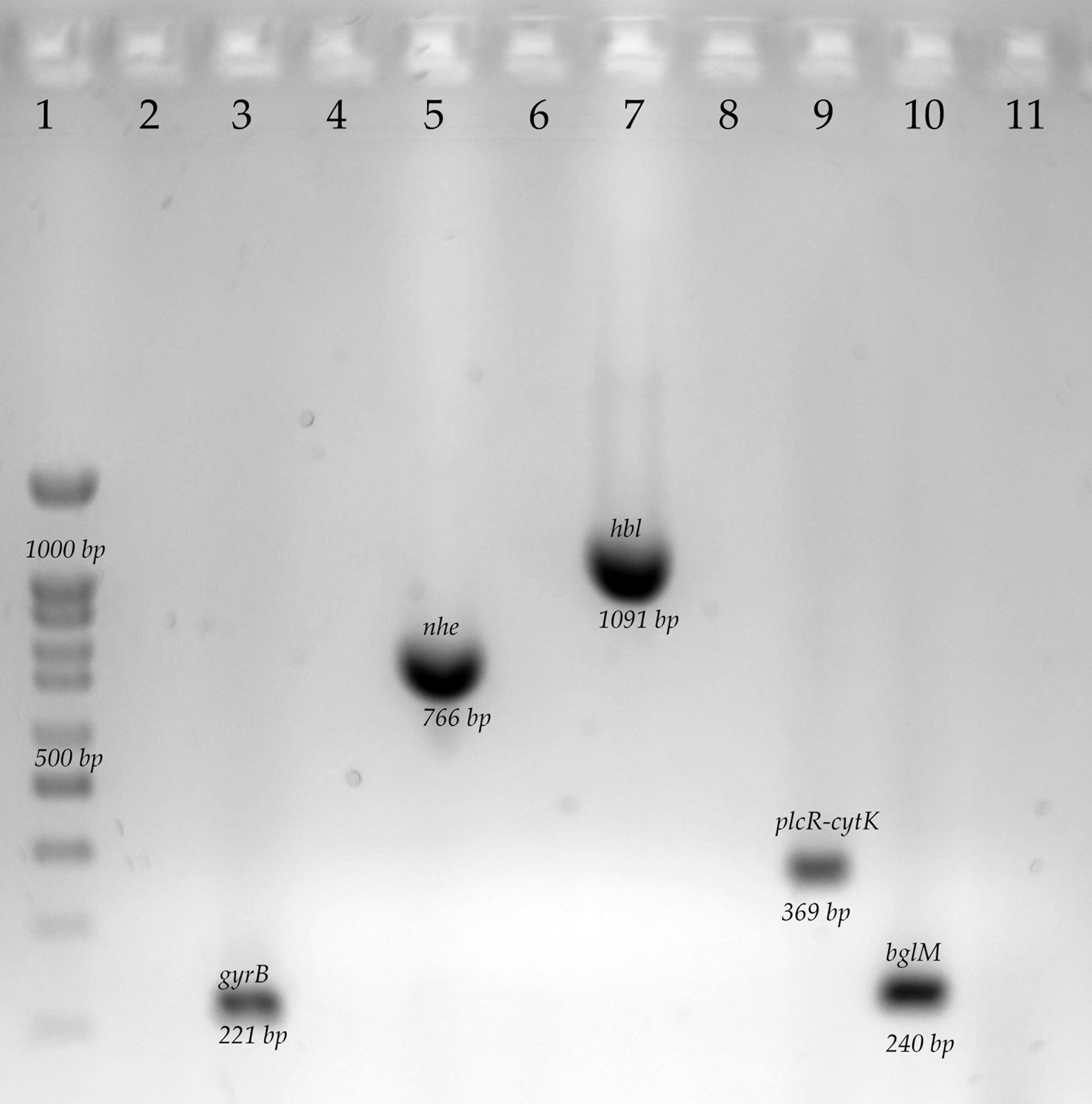

Molecular identification and toxin gene profiling of B. cereus isolatesThe chromosomal DNA was obtained by thermal shock from bacterial cultures. Briefly, cells from one colony were suspended in sterile water, heated at 95°C for 3min, and then placed on ice. After centrifugation, the supernatants were used as a template for the molecular identification of the Bacillus cereus group, enterotoxin profile, and genes that possibly participate in biofilm production.

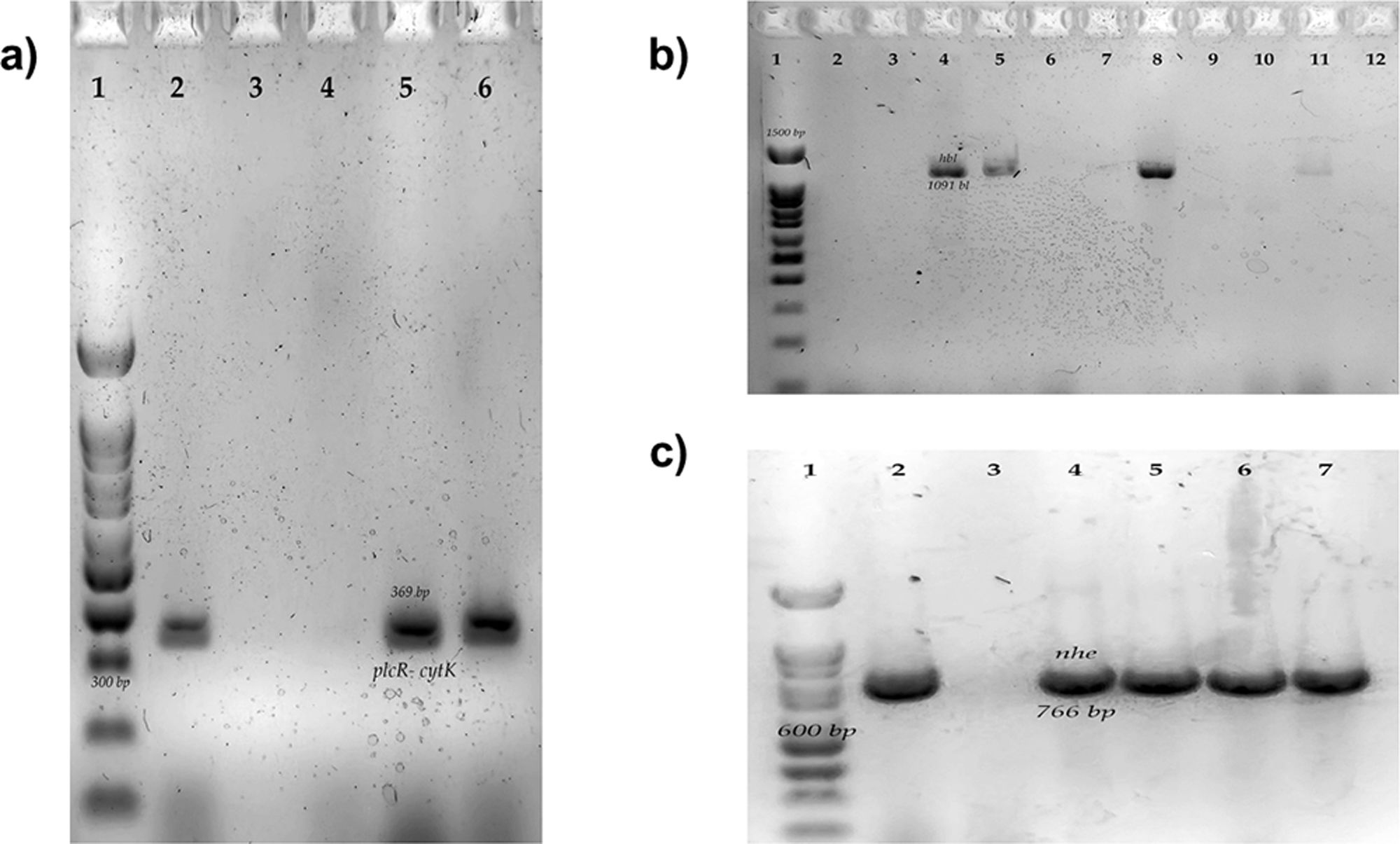

The differentiation of B cereus group was carried out by the amplification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to the gyrB gene and the toxin gene profiles from nheABC, hblABD, ces, and cytK gene. The final mix for each PCR reaction contained 0.2mM of each dNTP, 3mM MgCl2, 0.2μM of the primers, 1U of Taq DNA polymerase (Ampliqon, Odense, Denmark), 5μl of 10× buffer and 1μl of DNA as a template. The PCR cycling conditions and primers are shown in Table 1. We used a thermocycler for endpoint PCR (Applied Biosystem). A B. subtilis strain was used as a negative control, this strain was previously characterized in the laboratory. B. subtilis was originally isolated from vegetables1. The complete characterization of positive and negative strains is included in this manuscript (Fig. S1).

Primers sequences and cycling conditions used for molecular identification and toxin gene detection.

| Gene | Primer sequences | PCR cycling conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| gyrB | F – GCC CTG GTA TGT ATA TTG GAT CTA CR – GGT CAT AAT AAC TTC TAC AGC AGG A | Initial denaturation of 2min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30s, at 52°C for 1min and 72°C for 30s, and final elongation at 72°C for 10min | 49 |

| nheABC | F – AAG CIG CTC TTC GIA TTCR – ITI GTT GAA ATA AGC TGT GG | Initial denaturation of 5min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 49°C for 1min and at 72°C for 1min, and final elongation at 72°C for 5min | 15 |

| hblABD | F – GTA AAT TAI GAT GAI CAA TTT CR – AGA ATA GGC ATT CAT AGA TT | ||

| ces | F – TTG TTG GAA TTG TCG CAG AGR – GTA AGC GGA CCT GTC TGT AAC AAC | Initial denaturation of 2min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30s, at 52°C for 1min and 72°C for 30s and a final elongation at 72°C for 10min | |

| cytK-plcR | P1 – CAA AAC TCT ATG CAA TTA TGC ATP3 – ACC AGT TGT ATT AAT AAC GGC AAT C | Initial denaturation of 2min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30s, at 52°C for 1min and 72°C for 30s, and final elongation at 72°C for 10min | 40 |

| tasA | F – AGC AGC TTT AGT TGG TGG AGR – GTA ACT TAT CGC CTT GGA ATTG | Initial denaturation of 5min at 94C, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 59°C for 45s and 72°C for 45s, and final elongation at 72°C for 5min | 11 |

| sipW | F – AGA TAA TTA GCA ACG CGA TCTCR – AGA AAT AGC GGA ATA ACC AAGC | Initial denaturation of 5min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30s, 54°C for 45s, and 72°C for 45s, and a final elongation at 72°C for 5min |

Electrophoresis was performed on 2% agarose gels at 80V for 120min. The gels were stained with Midori Green (Nippon Genetics, Düren, Germany) and visualized with UV light. A 100bp molecular weight marker was used in all electrophoresis (CSL-MDNA-100BP, Cleaver Scientific Ltd., Warwickshire, England, UK).

Biofilm productionBefore the determination of static biofilms on polyvinylchloride (PVC), coupons of PVC were placed inside glass tubes. The coupons were rinsed to remove dirt and other organic components and were sterilized before the use. The biofilms were generated in brain heart infusion broth (BHI). Phenol red broth with or without dextrose was used at a concentration of 1% to assess the participation of carbohydrates (dextrose). Each glass tube containing the PVC coupon was filled with 1ml of the corresponding broth. The broths were inoculated with 1% volume of a 24-h culture (3ml). The tubes with the PVC coupons were incubated at 30°C for 48h under static conditions. For the determination in glass and polyethylene, the procedure was similar, but without the PVC coupons and tubes of each respective material. In the case of polystyrene, 96 well microplates were used, which were filled with 200μl of the respective broths and 1% of a 24-h culture. Incubation times were the same.

Next, the biofilm formation was measured by performing a safranin assay. Briefly, after incubation, the growth was read by removing 200μl of culture and reading it at an absorbance of 600nm. Then, in the case of PVC, the coupons were carefully washed three times by dipping them in saline phosphate buffer (PBS) (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using sterile tweezers. In the case of the glass and polyethylene tubes, as well as the polystyrene plates, the medium was removed, and they were washed three times with PBS. The adhered biofilm was stained with 0.1% safranin solution (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for 30min. At this point, in the case of glass, due to the volume of the medium used, it was possible to identify interface biofilms (a ring that forms in the glass tube at the limit of the culture medium) and submerged (those that form at the bottom tube). The coupons, the glass and polyethylene tubes, and the polystyrene plates were washed with PBS another three times and incubated with 70% ethanol for 30min to release the biofilm-bound safranin. The solubilized safranin was quantified by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 492nm. The safranin tests were repeated in three independent experiments. The culture medium without inoculum was used as a negative control. The formula proposed by Niu and Gilbert38 was used to determine the specific biofilm formation (SBF). Strains with values above 25% SBF were considered positive for biofilm production.

Motility determinationMotility was determined; for this, 3.5g/l of bacteriological agar (0.35%) was added to the respective broths used for biofilm production in to use them as a soft medium. This medium was poured into Petri dishes and allowed to gel before being inoculated. Ten μl of a 24h liquid bacterial culture was placed in the center of the plate. After the incubation times had elapsed, the size of the colony was measured with a vernier caliper. The tests were repeated in three independent experiments. A Klebsiella pneumoniae strain was used as a negative control.

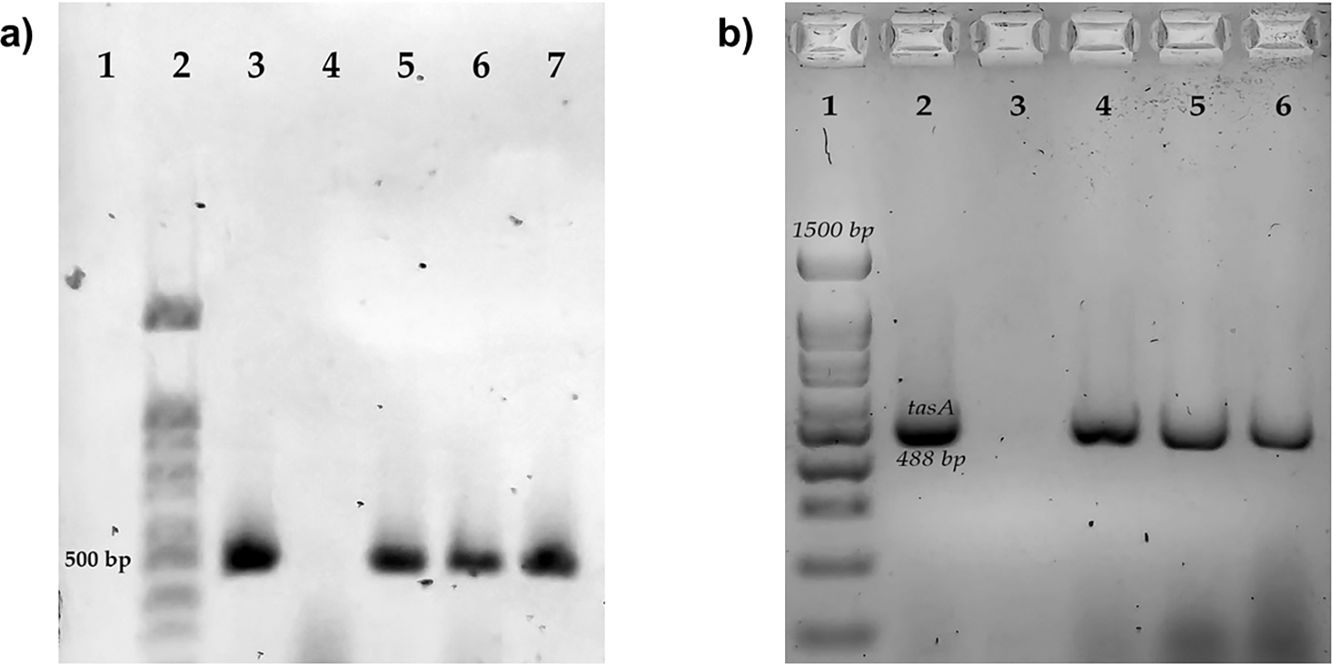

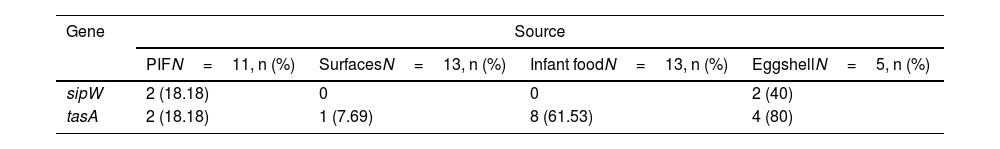

Determination of genes related to biofilm production in Bacillus cereus group isolatesGenes related to biofilm formation were determined by PCR amplification of the regions coding for tasA and sipW. The final mix for each PCR reaction contained 0.2mM of each dNTP, 3mM MgCl2, 0.2μM of the primers; 1U of Taq DNA polymerase (Ampliqon, Odense, Denmark), 5μl of 10× buffer and 1μl of DNA as a template. The PCR cycling conditions and primers are shown in Table 1. Electrophoresis was performed on 2% agarose gels at 80V for 45min. The gels were stained with Midori Green (Nippon Genetics, Düren, Germany) and visualized with LED light. We performed an in-silico analysis with the genome of strain B. cereus ATCC14579 and the primers described Table 1, observing the amplification of both genes of interest of the desired size, and we used strain B. cereus ATCC14579 as a positive control.

Statistical analysisResults per strain represent the average of at least three independent experiments. The effects of the material, source of isolation, and sugar supplementation on the formation of biofilms by strains of B. cereus group were compared using Mann–Whitney U for two groups or Kruskal–Wallis for more than two groups with a Bonferroni post hoc test and Tukey. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

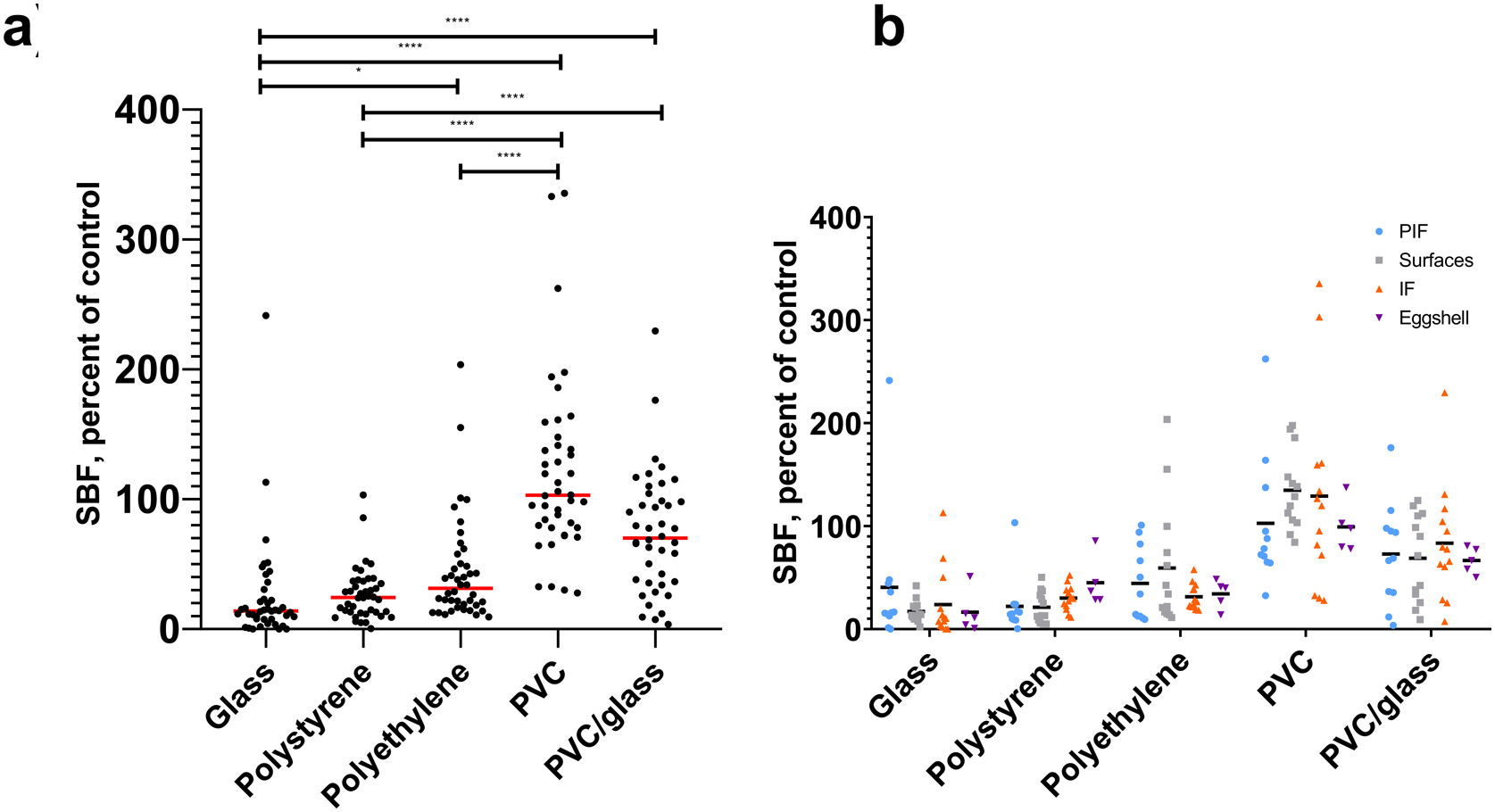

ResultsBiofilm production in different materials, sugar influence in biofilm productionThis study found differential biofilm production in BHI broth regarding the materials used. We observe a higher production of biofilms by strains (specific biofilm formation, SBF) in PVC (p<0.0001) and PVC glass (p<0.0001) compared to glass. Regarding the origin of isolation of the strains, we did not find statistically significant differences with the materials used (Fig. 1).

Biofilm production in different materials and by source isolation at 37°C with O2. (a) Biofilm production of B cereus group strains in different materials and (b) from source isolation: light blue circles, powered infant formula; gray squares, surfaces; orange triangles, infant food; purple triangles, eggshell. *p≤0.05, ****p≤0.0001. In the X axis are the materials and, in the Y, the specific biofilm formation (SBF). Top Kruskal–Wallis post hoc Dunn's. Lower ANOVA.

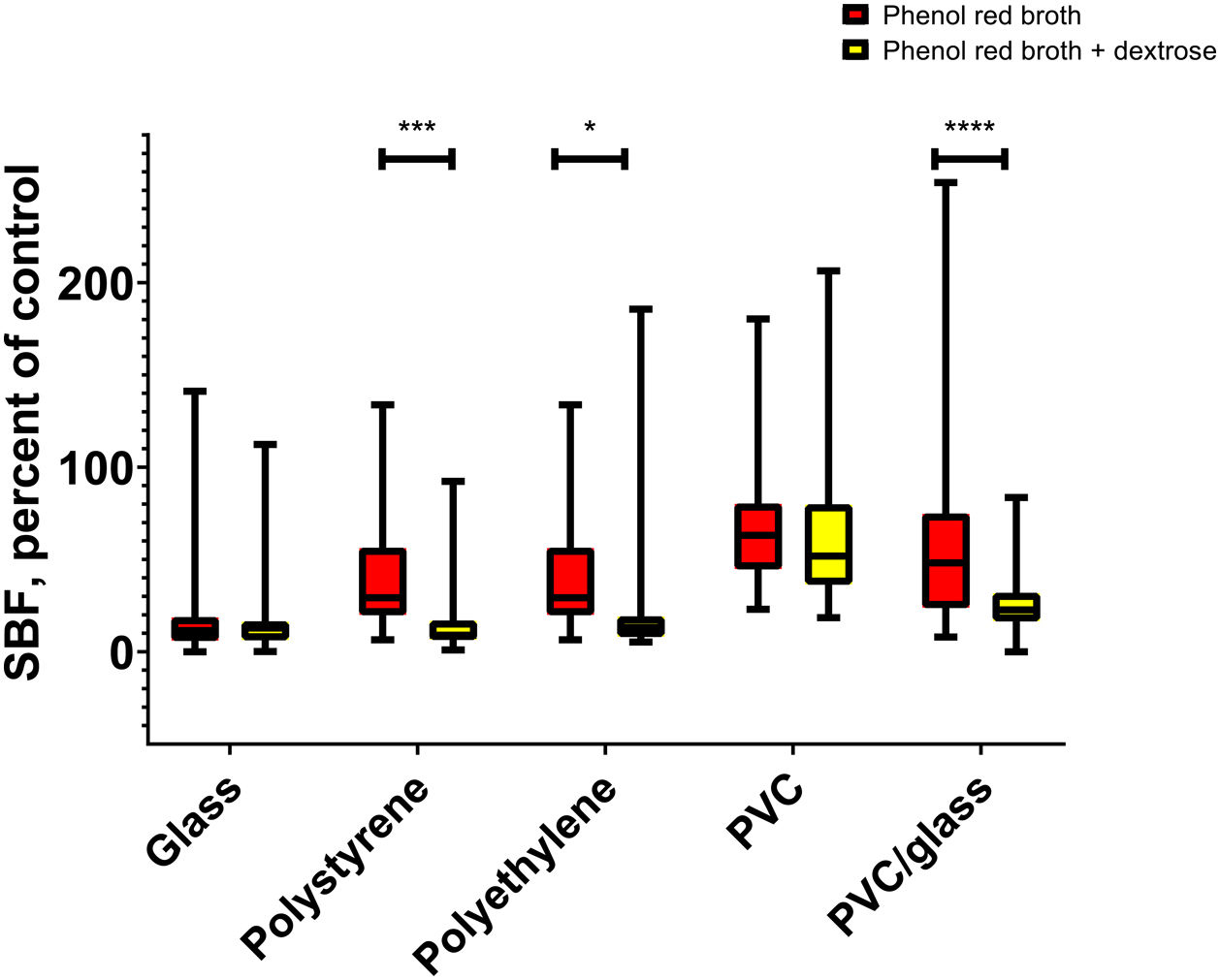

We compare biofilm production on different materials. When phenol red broth was supplemented or not with dextrose, we observed a higher production of biofilms in the absence of dextrose in the materials polystyrene (p=0.0002), polyethylene (p=0.02), and PVC glass (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Relationship between biofilm production and motility on different mediaThe relationship between biofilm production and motility was sought, finding a negative correlation during the production of biofilms in the glass with BHI broth (R=−0.320, p=0.039) (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, we compared the motility of the strains in semi-solid culture media BHI, phenol red, and phenol red with dextrose. We found that strains have higher motility in BHI than to phenol red (p=0.04) (Fig. 3b). When finding differences between motility in BHI and phenol red, it was expected to find differences in biofilm production. However, no statistically significant differences were found (Fig. 3c). However, when classified by type of biofilm, in the BHI broth (medium in which greater motility was observed), no submerged biofilms were found compared to phenol red broth and phenol red broth supplemented with dextrose (Fig. 3d).

Relationship between biofilm production and motility on different media. (a) Relationship between biofilm production and motility on BHI medium, (b) motility on different media, (c) biofilms production of 43 strains on glass on different media, and (d) biofilm type frequency on different media. The color blue is brain heart infusion broth/medium, the color red is phenol red broth/medium and the color yellow is phenol red broth/medium plus dextrose. (a) Spearman correlation, (b) Kruskal–Wallis post hoc Dunn's, and (c) Kruskal–Wallis.

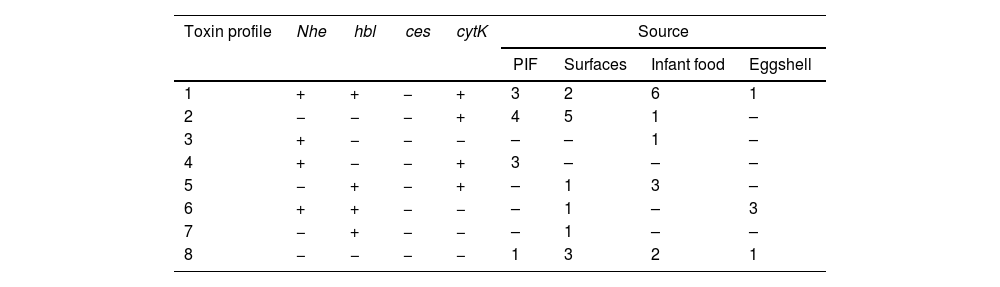

Regarding the enterotoxigenic profile, we did not find strains with the ces gene; but we identified eight different enterotoxigenic profiles, the most common being the profile that includes genes for the three enterotoxins (NHE, HBL, and CYTK) (12/43, 27.9%); When comparing them by origin, the profile mentioned above was the most common in isolated strains of the infant food; in the case of eggshell, the most common profile included the genes for the enterotoxins NHE and HBL; for strains isolated from surfaces and powdered infant formula, the profile that only had the cytotoxin K gene (cytK) was the most frequent; It is important to mention that most of the strains had at least one gene for one of the three most important enterotoxins of B. cereus (36/43, 83.72%) (Table 2 and Fig. S2).

Toxin gene profiles of Bacillus cereus group isolates by source.

| Toxin profile | Nhe | hbl | ces | cytK | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIF | Surfaces | Infant food | Eggshell | |||||

| 1 | + | + | − | + | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| 2 | − | − | − | + | 4 | 5 | 1 | – |

| 3 | + | − | − | − | – | – | 1 | – |

| 4 | + | − | − | + | 3 | – | – | – |

| 5 | − | + | − | + | – | 1 | 3 | – |

| 6 | + | + | − | − | – | 1 | – | 3 |

| 7 | − | + | − | − | – | 1 | – | – |

| 8 | − | − | − | − | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

PIF: powered infant formula.

This study includes two genes previously described as important for producing biofilms. We observed the sipW and tasA genes more frequently in the strains isolated from eggshells (Table 3 and Fig. S3). We compared biofilm production with the presence of these two genes; however, no significant differences were found (Fig. S4).

DiscussionIn this study, we worked with strains of the Bacillus cereus group isolated from different foods, which have previously been reported contaminated by this microorganism3,6,27,30,32,42,44,52, considering that biofilm production could be a strategy for contamination. We decided to include strains isolated from stainless steel metal surfaces because a greater production of biofilms on stainless steel plates has been described in other materials (polystyrene), in addition to the fact that biofilms or spores have been described on surfaces of this material17.

We decided to carry out the molecular identification of the B. cereus group by amplifying the gyrB gene (Fig. S1) because it is a technique that does not require gene sequencing, allowing a significant number of samples to be processed. Furthermore, Wei et al.49 describe that using this primer among 111 B. cereus strains, 106 strains were positive (95%). Non-members of the B. cereus group (B. amyloliquefaciens, B. subtilis, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Micrococcus luteus, Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes) were also subjected to the PCR assay to test the specificity of the primers. These strains showed no amplification (0/9).

The strains were able to produce biofilms in different materials, which are commonly used in the industry, such as PVC in product conveyor belts and glass, polystyrene, and polyethylene in the production of food containers and plastic containers20. In this study, we used the BHI culture medium to determine biofilms on these materials because, in this culture medium, greater production of biofilms by strains of the B. cereus group has been reported compared to the soybean trypticase medium or the phenol red1,25. The BHI medium contains nutrients from the brain heart infusion, peptone, and glucose components. The peptones and infusion are organic nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, vitamins, and trace substances. Glucose is the carbohydrate source that microorganisms utilize by fermentative action. The medium is buffered with disodium phosphate.

When determining the biofilms, we found statistically significant differences in PVC and glass/PVC compared to glass; these data have already been previously reported by Adame et al.1. In addition, various authors report the production of biofilms is different according to the material used. Hayrapetyan et al.25, report a higher production in stainless steel to polystyrene as well Wijman et al.50. These production differences may be related to these materials’ physicochemical characteristics, such as hydrophobicity13. Also, it is interesting that strains did not show differences in PVC or glass but showed a significant difference in PVC/glass. This phenomenon may be related to biofilms, once mature at 24h, could release spores or vegetative cells into the medium tube50, which could spread, and in this case, adhere to the glass.

We consider that the differences in biofilm production between materials could be related to the characteristics of the strain. Hayrapetyan et al.24, describe the genetic variability of B. cereus, which could be related to the different iron uptake systems inherent in the strains and could be related to the source of obtaining iron and, therefore, its ability to grow and form biofilms. It could also explain the effect of the origin of isolation of the strain. Hayrapetyan et al.25, compared biofilm production according to isolation without finding statistically significant differences. Various studies have found differences regarding the origin of isolation, Kamar et al.31, describe a greater production of biofilms in isolated strains of food poisoning to non-pathogenic strains. Auger et al.5, describe a higher production of biofilms in strains isolated from soil and gastrointestinal diseases than isolated ones from different non-gastrointestinal diseases. One possible explanation is the type of comparison; the authors described above consider different isolation sources (soil, gastrointestinal diseases, food). Our study is the same source of isolation from food, while the comparison is between different types of foods.

Previously, we reported the formation of biofilms using red phenol broth1. For this reason, we decided to continue working with this culture broth because it is an advantage the opportunity to supplement with carbohydrates and observe the effect on the production of biofilms. After all, an increase in the expression of genes related to fermentative pathways has been previously reported during biofilm production in B. cereus and products of these pathways strongly promote the production of biofilms such as ethanol and acetoin51. The red phenol broth is a complete medium without added carbohydrates. The pancreatic digest of casein provides nutrients and, is low in fermentable carbohydrates. The pH indicator, phenol red, is used to detect acid production. We use dextrose as a fermentable carbohydrate because all the strains utilize this carbohydrate. Were found a decrease in biofilm production in some materials in the presence of dextrose, but it was not a consistent result in all. The above could be explained because the production of biofilms is not only affected by the presence of carbohydrates in the medium; Okshevsky et al.39, identify 91 genes involved in the production of biofilms, and these genes encode functions such as chemotaxis, amino acid metabolism, and cell repair mechanisms. Also, it is mentioned that most of its mutants are not motile, which confirms the theory that motility is involved in the production of biofilms. In addition to carbohydrates and amino acids, it has been described that other trace elements could be important during the production of biofilms, such as iron or manganese25,29,51.

As described above, there is a decrease in the expression of genes related to motility during biofilm production. For this reason, we find a negative correlation between the motility of the strains on BHI agar and the production of biofilms in the glass. When strains with large motility halos were found, lower biofilms with this medium could be suspected. However, compared with phenol red broth and phenol red broth supplemented with dextrose, media in which lower motility halos were observed, no significant differences were determined. In the safranin method, at the time of incubation with 70% methanol, all the safranin adhered to the biofilm is released, regardless of the biofilm is an interface or submerged. We, therefore, consider performing an analysis according to the type of biofilm and culture media. We found that in the BHI broth (strains with higher motility halo), no strains with submerged biofilm production were found compared to the other media.

Regarding the production of submerged and interface biofilms with motility. Hayrapetyan et al.26, described that the mutant strains for rpoN did not present swarming-type halos (related to flagellum synthesis) and the biofilms produced were submerged. However, in the WT strain (B. cereus ATCC 1579) and in the strain in which rpoN was restored, the swarming halo and the formation of surface biofilms were observed. The above could explain the results obtained in BHI, where the strains with greater motility would form a greater quantity of surface biofilms. Houry et al.28, described that the flagellum is necessary for forming biofilms in the air-liquid. Hayrapetyan et al.25, described that most of the isolates from the food he used produce BHI air-liquid biofilms. They also explain that the production of submerged biofilms by strains in B. cereus in BHI medium is rare. In this sense, our results show that it is rare because the medium does not favor the production of this type of biofilm. Gao et al.21, report that B. cereus surface-associated biofilms takes place under conditions of glucose fermentation and depends on a drop in the pH of the medium.

In this study, to determine the toxigenic profile of the strains, we used the PCR technique implemented by Ehling-Schulz et al.15. These PCR allows a pair of primers for each enterotoxin to identify at least the joint presence of two subunits of the nheABC or hblABD operon. The above simplifies the search for enterotoxigenic strains of B. cereus. Also, Ehling-Schulz et al.15, describe those primers that allowed the detection of enterotoxin genes previously missed by PCR. According to enterotoxigenic profiles, it is important to mention the high frequency of strains with enterotoxigenic profile 1, which includes strains with genes for all three enterotoxins, which have been previously described2,12,15,30,41. In addition, the most common profiles included the nheABC operon and the cytK gene, which has been reported to be more frequent in strains isolated from food15. In this study, no strains with the ces gene were found; in this sense, various studies report negative or low results for this gene of interest4,47. The search for emetic strains is relevant because emetic strains represent a particular risk in heat-processed foods or preheated foods that are kept warm8. It is important to mention that most strains have at least one enterotoxin gene; it highlights their toxigenic potential. When strains are combined with biofilms, it could increase their importance in the food industry. However, a decrease in the expression of the nheABC and hblABD operons has been reported in strains during biofilm formation and has a lesser effect in HeLa cells. Also, it has been described that these cells, when shedding, can contaminate different products, change gene expression, and favor the production of toxins10.

The sipW and tasA genes have recently been described as orthologous genes of sipW and tasA of B. subtilis. They could fulfill the same function in biofilm formation, tasA codes for an amyloid protein, a structural component of B. cereus biofilms. SipW is a protein- related to the modification of tasA11. Previously, we showed the presence of these genes in strains of the B. cereus group; however, a few strains were used1. In this study, 43 strains were included where tasA was more prevalent to sipW, mentioning that all sipW-positive strains also had tasA, which their genetic arrangement could explain in the bacterial chromosome and their function11. This study found no statistically significant differences between tasA positive and negative strains.

On the one hand, we consider that the sequences where the primers have been designed are not conserved. Therefore, we consider that the primer design can be carried out in future studies, taking up this point. On the other hand, this could be related to the possible regulation of tasA either by the null or low expression of this protein during the production of biofilms under the experimental conditions tested. For example, Caro-Astorga et al.11, used TY broth and MSgg broth; unlike in this study, we used BHI broth and phenol red broth. Therefore, the analysis of the expression of this protein should be considered in the future. In addition, considering the contribution of other proteins to the exopolysaccharide matrix, such as capsular polysaccharide (eps2)9. Caro-Astorga et al.11, describe that wild-type cells formed visible rings after 24h of growth, which grew in thickness up to 72h; while ΔtasA strain, a thicker biomass ring, was observed at 24h, which disappeared at 72h. These observations revealed that this gene is important for biofilm formation in B. cereus. Considering the origin of isolation of the strain, a different distribution of these genes was observed in the strains used, being more common in strains isolated from infant food and egg. Even when no literature elucidates this behavior, it could be related to the genetic diversity of microorganisms and particular characteristics that allow them to contaminate certain food products.

The study highlights its importance due to an increase in the publication about B. cereus and the production of biofilms36, a mechanism that favors its environmental resistance, which was already facilitated by the production of endospores45 and that does not favor its eradication from food production environments43.

FundingThis research was funded by the Secretaría de Educación Pública. Itzel Maralhi Cruz Facundo had a student scholarship [966901] granted by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We appreciate the support in the preparation of the media and the different materials to Laura Isabel Reyna Terán and José Ángel Flores Ávila.