Occurrence of Ureaplasma diversum (U. diversum) has been associated with reproductive failures in cattle and detected in pigs with and without pneumonia. However, its role in the porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC) is unclear. A cross-sectional study was conducted in abattoirs, inspecting 280 pig lungs from eight herds. All the lungs were inspected, processed and classified according to the histopathological analysis. Moreover, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens were collected and processed by PCR for detection of U. diversum and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyopneumoniae). Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum and M. hyopneumoniae were detected in 17.1% and 29.3% of the analyzed BAL specimens, respectively. The concomitant presence of both microorganisms was detected in 12.5% of the inspected lungs. Both agents were found in lungs with and without pneumonia. M. hyopneumoniae was detected in 31.8% of pig lungs with enzootic pneumonia-like lesions, while Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum was detected in 27.5% of lungs with these lesions. This descriptive exploratory study provides information for future experimental and field-based studies to better define the pathogenic role of this organism within the PRDC.

La presencia de Ureaplasma diversum se ha asociado a fallas reproductivas en el ganado bovino y se ha detectado en cerdos con y sin neumonía. Sin embargo, su participación en el complejo de enfermedades respiratorias porcinas (CERP) no es clara. Se llevó a cabo un estudio transversal en matadero, inspeccionando 280 pulmones de cerdo provenientes de ocho piaras. Todos los pulmones fueron inspeccionados, procesados y clasificados según el análisis histopatológico. También se colectaron muestras de lavado broncoalveolar (LBA) y se procesaron mediante PCR para la detección de U. diversum y Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Ureaplasma sp.-U. diversum y M. hyopneumoniae se detectaron en el 17,1% y en el 29,3% de los LBA analizados, respectivamente. La presencia concomitante de ambos microorganismos se detectó en el 12,5% de los pulmones inspeccionados. Ambos agentes se encontraron en pulmones con y sin neumonía. M. hyopneumoniae se detectó en el 31,8% de los pulmones con lesiones compatibles con neumonía enzoótica, mientras que Ureaplasma sp.-U. diversum se detectó en el 27,5% de los pulmones con estas lesiones. Este estudio exploratorio descriptivo proporciona información para futuros estudios experimentales y de campo tendentes a definir mejor el papel patógeno de este organismo dentro del CERP.

Ureaplasma diversum (U. diversum) is considered one of the most important members of the family Mycoplasmataceae causing reproductive failure in cattle. U. diversum has also been detected in pneumonic cattle14. In pigs, it was first detected in animals with and without pneumonia1,2 and recently in nasal swabs of live pigs11. However, there is a lack of information on this microorganism with regard to its distribution and participation in the multifactorial porcine respiratory disease complex (PRDC). While Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyopneumoniae) is the primary agent of the PRDC, co-infections with other pathogens such as viruses and bacteria are frequent10. Although the concomitant presence of M. hyopneumoniae with other Mycoplasma species, including Mycoplasma hyorhinis (M. hyorhinis) and Mycoplasma flocculare has been reported5,7, there has been scant confirmatory evidence of the important role of these Mollicutes in M. hyopneumoniae infections. Furthermore, recent swine lung microbiome studies have demonstrated that members of the family Mycoplasmataceae are one of the most common microbial families in pig lungs with and without pneumonia13. Although other Ureaplasma species, such as Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum, have been detected in pig lungs13, there are only limited reports of the presence of U. diversum with other Mollicutes in pneumonic pig lungs1,2. The objectives of this study were: (i) to detect U. diversum in abattoir-collected pig lungs at the individual and herd level and (ii) to determine the concomitant presence of U. diversum and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae.

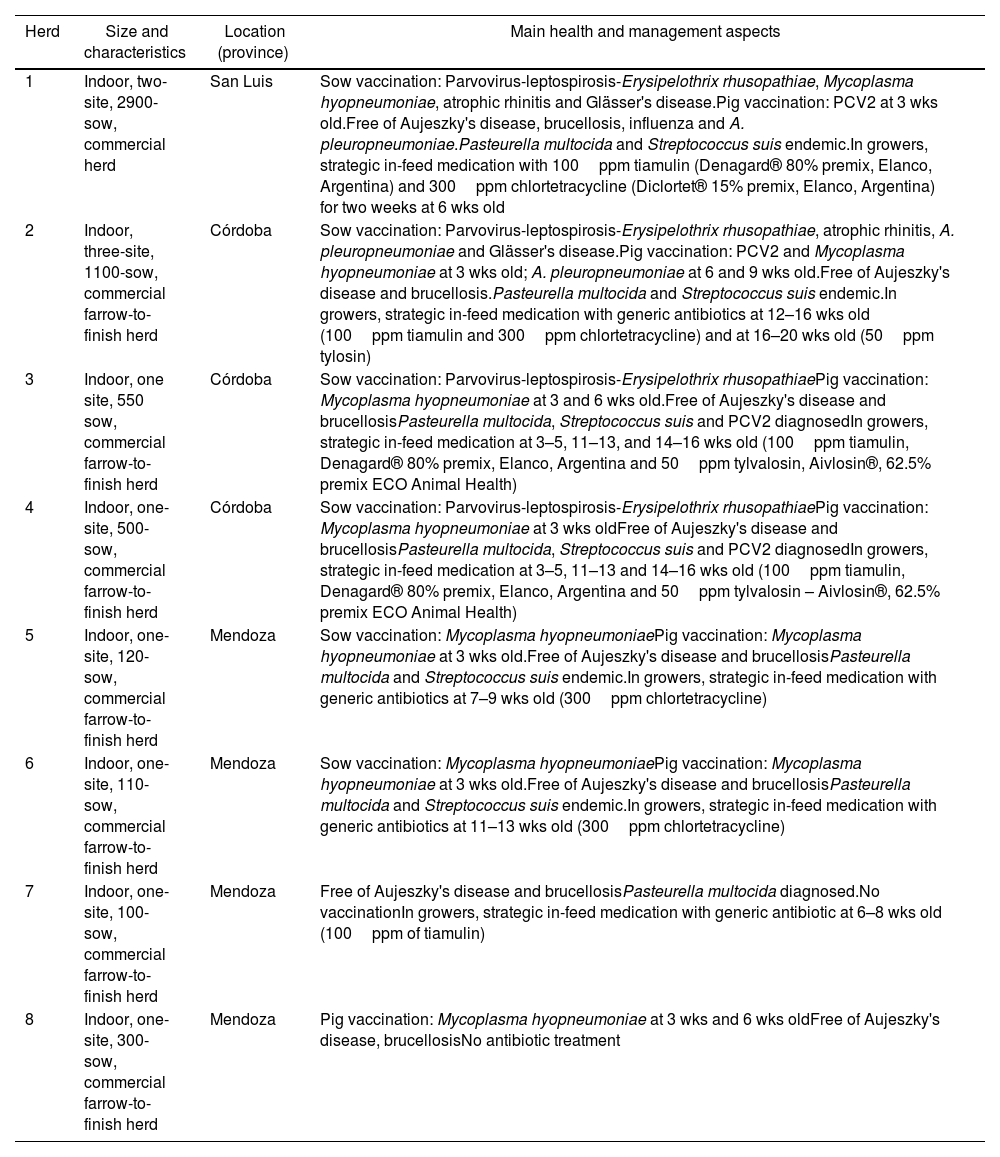

A cross-sectional study was conducted in five abattoirs involving eight Argentinian herds (1–8) from three provinces (Table 1). The main characteristics of the herds, such as type of system, size (number of sows) and main aspects of health management are shown in Table 1. Lung samples were collected using systematic random selection procedures where the first unit is randomly selected followed by selection at equal intervals. The herd sample size was set in 20, 40 and 60 lungs for herds with less than 500 sows, between 500 and 1000 sows, and more than 1000 sows, respectively. Each lung was grossly inspected for enzootic pneumonia (EP)-like lesions. Briefly, looking for purple to grey areas of pulmonary consolidation, located in the apical, intermediate, accessory and cranial parts of the diaphragmatic lobes10. Then, the type of pneumonia was determined by histopathological examination. For each inspected lung two specimens were collected using the following criteria: if the lung showed any macroscopic lesion compatible with EP-like pneumonia, a BAL sample (for PCR) and a piece of lung (for histopathological examination, in 10% buffered formalin) were collected for the affected lobe. Each BAL specimen was collected by a cut made in the affected lobe and a sterile 3ml plastic pipette with sterile saline was introduced into the secondary or tertiary bronchi adjacent to the lesion. In case no gross lesions were detected, the specimens were collected from the right middle lobe. For the histopathological analysis, lung tissues were formalin-fixed, paraffin wax embedded and haematoxylin and eosin (H–E) stained. To determine EP-compatible lesions, each sample was graded from 0 to 4, according to the criteria described by Calsamiglia et al.3. Lesions scoring 1–2 were considered nonspecific pneumonias and 3–4 were considered to be compatible with EP. DNA from 280 BAL samples was extracted using the commercial Puri-Prep S kit (Inbio-Highway, Argentina) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For both, U. diversum and M. hyopneumoniae detection, species-specific nested PCRs were performed under the conditions reported by Cardoso et al.4 and Calsamiglia et al.3, respectively. Considering that Cardoso et al.4 reported a specificity of 73.1% using this PCR in bovine samples and in order to verify the specificity of this reaction within pig lung samples, two U. diversum PCR positive samples from each herd were randomly selected for sequencing. The 18 PCR products obtained were purified (Puriprep-GP Kit, Inbio Highway), quantified and sequenced (ABI 3130xl; Applied Biosystems) using the inner primers described by the authors4. The sequences were curated using the BioEdit software6 and aligned using Clustal Omega software to obtain a consensus sequence (along with other sequences obtained from nasal swabs specimens from pigs)11. Then, the consensus sequence was aligned against the database using nucleotide BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast) excluding environmental sample sequences. The proportion of positive pigs was based on the number of PCR-positive specimens for M. hyopneumoniae, Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum or both, among the number of analyzed samples. Herds were classified as positive if at least one specimen rendered a positive result, and negative if all specimens were negative. The proportion of positive herds was based on the number of positive results among the total number of analyzed herds. The positive pig distribution among the type of microscopic lung was described. A contingency table and a test of independence based on a chi-square distribution was used with the level of significance set at 0.05.

Description of study herds, showing production type, number of sows, location and main health and management aspects.

| Herd | Size and characteristics | Location (province) | Main health and management aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indoor, two-site, 2900-sow, commercial herd | San Luis | Sow vaccination: Parvovirus-leptospirosis-Erysipelothrix rhusopathiae, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, atrophic rhinitis and Glässer's disease.Pig vaccination: PCV2 at 3 wks old.Free of Aujeszky's disease, brucellosis, influenza and A. pleuropneumoniae.Pasteurella multocida and Streptococcus suis endemic.In growers, strategic in-feed medication with 100ppm tiamulin (Denagard® 80% premix, Elanco, Argentina) and 300ppm chlortetracycline (Diclortet® 15% premix, Elanco, Argentina) for two weeks at 6 wks old |

| 2 | Indoor, three-site, 1100-sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Córdoba | Sow vaccination: Parvovirus-leptospirosis-Erysipelothrix rhusopathiae, atrophic rhinitis, A. pleuropneumoniae and Glässer's disease.Pig vaccination: PCV2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at 3 wks old; A. pleuropneumoniae at 6 and 9 wks old.Free of Aujeszky's disease and brucellosis.Pasteurella multocida and Streptococcus suis endemic.In growers, strategic in-feed medication with generic antibiotics at 12–16 wks old (100ppm tiamulin and 300ppm chlortetracycline) and at 16–20 wks old (50ppm tylosin) |

| 3 | Indoor, one site, 550 sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Córdoba | Sow vaccination: Parvovirus-leptospirosis-Erysipelothrix rhusopathiaePig vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at 3 and 6 wks old.Free of Aujeszky's disease and brucellosisPasteurella multocida, Streptococcus suis and PCV2 diagnosedIn growers, strategic in-feed medication at 3–5, 11–13, and 14–16 wks old (100ppm tiamulin, Denagard® 80% premix, Elanco, Argentina and 50ppm tylvalosin, Aivlosin®, 62.5% premix ECO Animal Health) |

| 4 | Indoor, one-site, 500-sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Córdoba | Sow vaccination: Parvovirus-leptospirosis-Erysipelothrix rhusopathiaePig vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at 3 wks oldFree of Aujeszky's disease and brucellosisPasteurella multocida, Streptococcus suis and PCV2 diagnosedIn growers, strategic in-feed medication at 3–5, 11–13 and 14–16 wks old (100ppm tiamulin, Denagard® 80% premix, Elanco, Argentina and 50ppm tylvalosin – Aivlosin®, 62.5% premix ECO Animal Health) |

| 5 | Indoor, one-site, 120-sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Mendoza | Sow vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniaePig vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at 3 wks old.Free of Aujeszky's disease and brucellosisPasteurella multocida and Streptococcus suis endemic.In growers, strategic in-feed medication with generic antibiotics at 7–9 wks old (300ppm chlortetracycline) |

| 6 | Indoor, one-site, 110-sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Mendoza | Sow vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniaePig vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at 3 wks old.Free of Aujeszky's disease and brucellosisPasteurella multocida and Streptococcus suis endemic.In growers, strategic in-feed medication with generic antibiotics at 11–13 wks old (300ppm chlortetracycline) |

| 7 | Indoor, one-site, 100-sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Mendoza | Free of Aujeszky's disease and brucellosisPasteurella multocida diagnosed.No vaccinationIn growers, strategic in-feed medication with generic antibiotic at 6–8 wks old (100ppm of tiamulin) |

| 8 | Indoor, one-site, 300-sow, commercial farrow-to-finish herd | Mendoza | Pig vaccination: Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at 3 wks and 6 wks oldFree of Aujeszky's disease, brucellosisNo antibiotic treatment |

Vaccination schedules and antibiotic treatments of piglets are described in greater detail. For sows, only the vaccines used are described.

PCV2: Porcine Circovirus type 2; wks old: weeks old.

M. hyopneumoniae and Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum were detected in 29.3% (95% CI 24.0–34.6) and 17.1% (95% CI 12.7–21.6) of the analyzed BAL specimens, respectively. The concomitant presence of both microorganisms was detected in 12.5% (95% CI 8.6–16.4) of pig lungs. All herds were positive for at least one of the evaluated specimens; in all herds M. hyopneumoniae was detected alone or in combination with Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum, while U. diversum was detected in 7 out of the 8 herds. The proportion of positive pigs in each herd ranged between 40% and 90%. Table 2 shows the proportions of PCR positives for M. hyopneumoniae alone, Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum alone or mixed detection and the proportion of macroscopic and microscopic lung lesions. The 16S ribosomal RNA consensus sequence obtained – 173 pb – (GenBank accession number ON059750) showed 100% similarity with the same region of U. diversum strains ATCC 49782 (CP009770.1: GU227397.1), T95 (JN935894.1), ATCC 49783 (GU227398.1) and A417 (NR_025878.1), and Ureaplasma sp. strains USP45 (GU227392.1), USP4 (GU227390.1), USP3012 (GU227389.1) and USP47 (GU227388.1). Among the 280 lungs examined, 125 (44.6%) and 110 (39.3%) had no macroscopic and microscopic lesions of pneumonia respectively. Of the 170 lungs with microscopic lesions, 66 (38.8%; 95% CI 31.2–46.4) were diagnosed as EP-like lesions (scored as 3–4) and 104 (61.2%; 95% CI 53.6–68.8) as nonspecific pneumonias, scored as 1–2 (Table 2). Table 3 shows the proportion of each type of pneumonia diagnosed by histopathological examination for all PCR results from the BAL specimens; from the data, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the histopathological diagnosis and PCR results are dependent on each other. Among the lungs diagnosed as EP-like lesions, an overlap of the confidence intervals was observed, indicating that there were no differences between the proportion of diagnoses by PCR, while among the lungs diagnosed as nonspecific lesions the proportion of PCR positives for M. hyopneumoniae alone was higher than for Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum alone or mixed detection.

Proportion (percentage and 95% confidence interval) of BAL PCR-positive specimens for Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum and/or Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and lungs with macroscopic and microscopic lung lesions, according to the herds.

| Herd | Lung pathology (%; 95% CI) | PCR positive (%; 95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macroscopic EP-like lesions | Microscopic lesions (scored 1–4) | M. hyopneumoniae | U. diversum–Ureaplasma spp. | U. diversum–Ureaplasma spp. and M. hyopneumoniae | |

| 1 | 38/60(63.3; 50.3–76.3) | 41/60(68.3; 55.7–80.9) | 19/60(31.7; 19.9–43.4) | 1/60(1.7; −1.6–4.9) | 9/60(15; 6–24) |

| 2 | 21/60(35; 22–47.9) | 23/60(38.3; 25.2–51.5) | 13/60(21.7; 11.2–32.1) | 6/60(10; 2.4–17.6) | 5/60(8.3; 1.3–15.3) |

| 3 | 17/40(42.5; 25.9–59) | 19/40(47.5; 30.7–64.2) | 1/40(2.5; −2.3–7.3) | 20/40(50; 34.5–65.5) | 15/40(37.5; 22.5–52.5) |

| 4 | 28/40(70; 54.5–85.4) | 28/40(70; 54.5–85.4) | 15/40(37.5; 22.5–52.5) | 0/40(0; 0–0) | 1/40(2.5; −2.3–7.3) |

| 5 | 13/20(65; 40.7–84.6) | 15/20(75; 50.9–91.3) | 4/20(20; 2.5–37.5) | 6/20(30; 9.9–50.1) | 3/20(15; −0.6–30.6) |

| 6 | 10/20(50; 25.6–74.4) | 13/20(65; 40.7–84.6) | 18/20(90; 76.9–103.1) | 0/20(0; 0–0) | 0/20(0; 0–0) |

| 7 | 13/20(65; 40.7–84.6) | 13/20(65; 40.7–84.6) | 0/20(0; 0–0) | 14/20(70; 49.9–90.1) | 1/20(5; −4.6–14.6) |

| 8 | 15/20(75; 50.9–91.3) | 18/20(90; 68.3–98.8) | 12/20(60; 38.5–81.5) | 1/20(5; −4.6–14.6) | 1/20(5; −4.6–14.6) |

| Total | 155/280(55.3; 49.3–61.4) | 170/280(60.7; 54.8–66.6) | 82/280(29.3; 23.7–34.8) | 48/280(17.1; 12.5–21.7) | 35/280(12.5; 8.4–16.5) |

Proportion (percentage and confidence interval 95%) of BAL PCR-positive or negative specimens for Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum and/or M. hyopneumoniae according to the type of lesion diagnosed by histopathological examination in 280 lungs.

| PCR results | Lung pathology (%; 95% CI) | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No lesion | Nonspecific lesions(scored as 1–2) | EP-like lesions(scored as 3–4) | ||

| M. hyopneumoniae | 18/110(16.4; 9.5, 23.3) | 43/104(41.3; 31.9, 50.8) | 21/66(31.8; 20.6, 43.1) | 82/280(29.2%: 23.7–34.8) |

| Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum | 16/100(14.5; 8, 21.1) | 14/104(13.5; 6.9, 20) | 18/66(27.3; 16.5, 38) | 48/280(17.1%: 12.5–21.7) |

| Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum and M. hyopneumoniae | 17/110(15.5; 8.7, 22.2) | 8/104(7.7; 2.6, 12.8) | 10/66(15.2; 6.5, 23.8) | 35/280(12.5%; 8.4–16.5) |

| Negative | 59/110(53.6; 44.3, 63) | 39/104(37.5; 28.2, 46.8) | 17/66(25.8; 15.2, 36.3) | 115/280(41%: 35.1–47) |

The nested PCR used in this study for U. diversum detection was developed and originally tested in clinical specimens from bovines with a specificity of about 73%4. The obtained sequencing and alignment results showed that their specificity was not enough for the identification of U. diversum, since other close-related Ureaplasma species could be detected. Other specific molecular techniques should be used in future studies for specific U. diversum detection. Despite this fact, there are no antecedents in the literature about the detection of U. diversum and other close-related species in pig lungs at herd level. Given the low sensitivity of culture and the availability of PCR in our laboratory, we did not attempt a culture of Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum in this study but relied on molecular diagnostics to confirm their presence in the BAL samples. Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum were detected in BAL fluid from lungs of approximately 17% of finisher pigs of slaughter age, a proportion greater than that previously reported in pigs from Cuba and Canada, with 6.6% and 3.85%, respectively1,2. It is important to note here that the positive proportion of both, Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum and M. hyopneumoniae, might be overestimated, considering that the scalding tank has been highlighted as a critical point of cross contamination during the slaughtering process8. However, we recently estimated a prevalence of 16.5% of Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum in nasal swabs specimens from 6–8 and 15–22 weeks-old pigs11. These results might indicate, that a similar proportion of pigs carry Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum at different sites in the respiratory tract and at different ages. Further studies are needed to understand this phenomenon. On the one hand, the evaluation of lung lesions in abattoirs is limited because it only identifies chronic (or recent) lung lesions at the end of the production period and does not provide any information regarding the evolution of respiratory diseases in younger pigs12. On the other hand, a limitation of gross lung lesion evaluation in abattoirs is that other agents may also cause macroscopic lesions similar to those induced by mycoplasmas10,12. Thus, a histological examination is important in lesion characterization. With regard to microscopic lesions, BALT hyperplasia has so far been associated with M. hyopneumoniae and M. hyorhinis7,12 in spite of the fact that the role of M. hyorhinis in the PRDC is still controversial5,7. In this case, only Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum were detected in 27.3% of EP-like lesions (scored as 3–4). Furthermore, negative PCR results were obtained in 25.8% of EP-like lesions. Not having searched for M. hyorhinis is a limitation of this study. However, a putative relationship between the presence of Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum with lung lesions cannot be strictly ruled out, especially considering previous findings in which U. diversum has been detected in lungs with EP-like lesions2. Experimental studies should be conducted to confirm if Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum can produce chronic lung inflammation, resulting in BALT hyperplasia. Our second objective, to determine the concomitant presence of U. diversum and M. hyopneumoniae, resulted in evidence of mixed infection in almost 13% of BAL samples. This is an important finding since there are scarce antecedents about the presence of Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum together with other Mollicutes2. However, this type of mixed infection would not be rare, mainly due to the abundance of Ureaplasma and other Mollicute species within the pig lungs5,7,13. While pathogenic mechanisms of U. diversum in pigs remain unknown, there are already antecedents of the presence of the agent associated with lung lesions in other species. Human Ureaplasma sp. closely related to U. diversum are capable of causing pneumonia15, and U. diversum has been detected in pneumonic calves14. In pigs with pneumonia, not only U. diversum but also other species of the genus Ureaplasma have been detected1,13. The identification of surface molecules and capsular material involved in the interaction of U. diversum with the host, and virulence factors including the Mycoplasma immunoglobulin binding/Mycoplasma immunoglobulin protease (MIB-MIP) system9, most of them also present in M. hyopneumoniae, suggest that this organism has a pathogenic potential. This descriptive exploratory study provides information that can be used to design experimental and field-based studies to better define the pathogenic role of this organism within the PRDC.

This study represents a comprehensive investigation of Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum presence in pig lungs at the individual and herd level. The concomitant presence of Ureaplasma sp.–U. diversum with M. hyopneumoniae was demonstrated in BAL, being the first study to investigate such an association on a large field-based scale.

Conflict of interestNone reported.

This study was financially supported in part by FONCyT-ANPCyT-MinCyT, República Argentina [PICT 02148/2018]; and SeCyT-UNRC, República Argentina [PPI 2020-2022]. J.S. was holder of an “Ayudantía de Investigación” scholarship during the development of this study (UNRC).