We subtyped 32 Salmonella enterica strains isolated from carcasses (n=10), the environment (n=14), head meat (n=1) and viscera washing and chilling water (n=7) in provincial abattoirs with no Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system from Buenos Aires, Argentina, before and after implementing improvement actions. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was carried out using the XbaI restriction enzyme. Strains belonged to six serovars, from which 10 restriction patterns were obtained (five unique patterns and five clusters). We found different clones of S. enterica serovars in the same abattoir by XbaI-PFGE. In addition to promoting good hygiene practices, the implementation of an HACCP plan is necessary to meet the zero-tolerance criteria for Salmonella on beef.

Subtipificamos en total 32 cepas de Salmonella enterica aisladas de carcasas (n=10), medio ambiente (n=14), carne de cabeza (n=1) y agua de lavado y enfriamiento de vísceras (n=7) en frigoríficos provinciales de Buenos Aires (Argentina) sin análisis de peligros y puntos críticos de control (hazard analysis critical control point [HACCP]); la toma de muestras se efectuó antes y después de implementar acciones de mejora. Se llevó a cabo electroforesis en gel de campo pulsado (PFGE) utilizando la enzima de restricción XbaI. Las cepas pertenecían a 6 serovares y presentaron 10 patrones de restricción (5 patrones únicos y 5 clusters). Demostramos la presencia de diferentes serovares de S. enterica en un mismo frigorífico mediante XbaI-PFGE. Además de las buenas prácticas de higiene, se requiere la aplicación de un HACCP para cumplir con los criterios de tolerancia cero para Salmonella en carne bovina.

Salmonellosis represents an important public health concern worldwide, with an estimated 93.8 million gastroenteritis cases and 155,000 deaths annually due to Salmonella species, of which 85.6% are foodborne. Human salmonellosis has been associated with contaminated food products, primarily those of animal origin, as well as with direct contact with infected animals7. Salmonella spp. contaminate meat in the abattoir during slaughter by spreading from the hide and the intestinal tract of animals. Moreover, knives, workers, platforms and equipment can become sources of cross contamination14.

Argentine bovine abattoirs are classified into exporter, federal transit and provincial transit5, and have different hygiene and sanitation standards. Provincial transit abattoirs do not always have a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system; although they comply with the sanitary requirements of each provincial health authority, they do not implement the microbiological verification of either product or the environment5. Thus, meeting the zero tolerance criteria for Salmonella is quite difficult in abattoirs with no HACCP system. In our country, characterization and subtyping studies of this bacterial group in bovine abattoirs have not been previously conducted. For this reason, knowledge about circulating Salmonella spp. clones in this environment is scarce.

We have previously demonstrated that the prevalence of Salmonella enterica in products, by-products and environmental samples can be reduced by implementing improvement actions and food handlers’ training5. The aim of the present work was to characterize S. enterica isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in order to establish their epidemiological relationships, contamination routes and spread in abattoirs.

We subtyped 32 Salmonella enterica strains previously isolated from three provincial abattoirs with no HACCP system from Buenos Aires, Argentina during 2016–20185. For that purpose, the provincial health authority selected three licensed abattoirs (identified as A, B and C) located at less than 100km from the sample processing laboratory, each of them with an average slaughter of 150–200 animals per day5.

Samplings included carcasses (n=252), the environment (n=252, involving workers’ hands, knives, workers’ boots, platforms, cool chambers and bathroom), head meat (n=21) and viscera washing and chilling water (n=105, involving heart, sweetbread, liver, kidney and chitterlings). Isolation of Salmonella spp. was carried out according to ISO 6579-1:20176. In the baseline study5, 26 strains were isolated in 2016 before implementing improvement actions (stage I; 10 samplings per establishment), and other six strains were isolated in 2018 after their implementation (stage III; 4 samplings per establishment), although it was not possible to implement an HACCP plan5. Salmonella spp. strains were isolated from carcasses (n=10), the environment (n=14), head meat (n=1) and viscera washing and chilling water (n=7). The strains belonged to six serovars: Anatum (n=14), Montevideo (n=12), Typhimurium (n=2), Give (n=2), Cerro (n=1) and Newport (n=1) 5.

For the PFGE analysis, the one-day (24–26h) PulseNet standardized laboratory protocol4 for molecular subtyping of Salmonella serotypes was employed. Restriction digestion of DNA in agarose plugs was carried out with the XbaI enzyme (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). MaestroGen slider imager (Maestrogen Inc., Nevada, USA) was used to obtain PFGE images of the gels. Tagged file format (TIFF) image analysis was conducted using the BioNumerics version 6.6 software package (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) using the Dice coefficient and the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) to generate dendrograms with 1.5% band matching tolerance. Two or more isolates were grouped into a cluster when they shared an identical pattern (100% similarity).

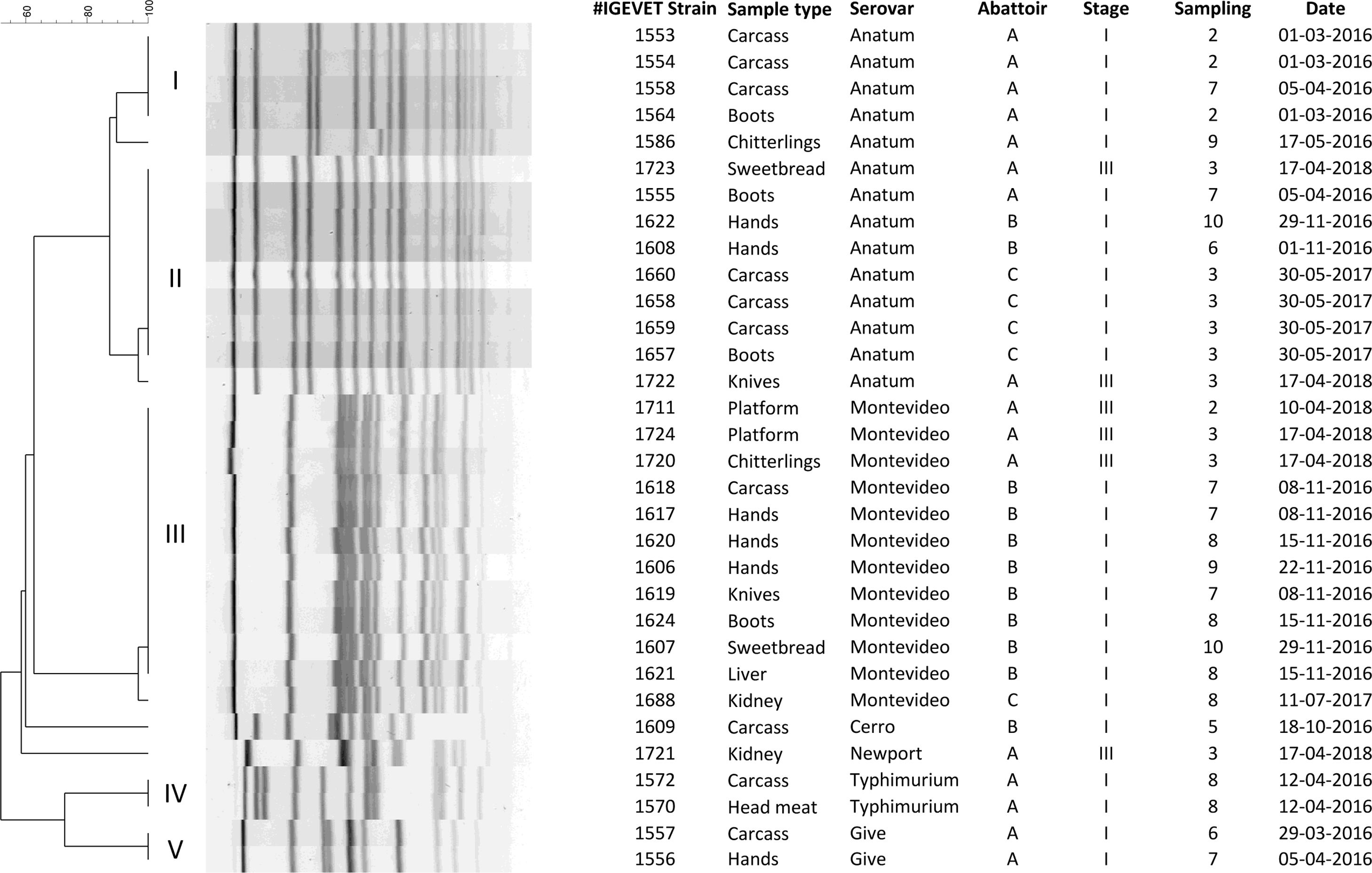

A dendrogram with 10 restriction patterns with at least 51.8% similarity was obtained. Five unique patterns and five clusters were obtained (Fig. 1). Isolates from serovar Anatum showed four patterns (two corresponding to unique strains and the other two in more than one isolate) with at least 87.4% similarity. Cluster I included four isolates from abattoir A obtained from carcasses (n=2) and workers’ boots (n=1) on sampling 2, and carcass (n=1) on sampling 7. These findings would indicate cross-contamination by direct contact with carcasses; persistence of contamination for more than a month in the abattoir environment would become a possible source of environmental contamination8.

Cluster II included eight strains of serovar Anatum, from the three abattoirs studied. In abattoir A, one strain was isolated from workers’ boots in 2016 and another from sweetbread washing and cooling water in 2018. The ability of S. anatum to persist in the environment for years has already been described by Carlson et al3. On this basis, we hypothesized that the strains were circulating, persisted in the animals and contaminated the establishment at different times with the same clone, or that the strains persisted in the abattoir environment. In abattoir B, two strains were isolated from workers’ hands on different samplings. In abattoir C, four clonal isolates were obtained from three different carcasses and workers’ boots on the same sampling. This highlighted the importance of reinforcing good hygiene practices (GHP), since workers would be a possible source of contamination of the final product15.

S. Montevideo serovars (n=12) were grouped into the same cluster (III) with at least 96.8% similarity, except for one strain from abattoir C that gave a unique pattern. In abattoir B, the strains were isolated from carcasses, workers’ hands and knives on sampling 7; from workers’ hands, boots and liver washing and cooling water on sampling 8; from workers’ hands on sampling 9, and from sweetbread washing and cooling water on sampling 10. The presence of clones for more than one month evidenced the capacity of S. Montevideo to persist in the environment3. Additionally, the same clone was isolated from workers’ hands during three consecutive samplings, showing its persistence among workers, thus entailing an additional risk, namely, the propagation of these strains in and out of the abattoir. In abattoir A, the strain was isolated from platforms on two successive samplings (2 and 3) and from chitterling washing and cooling water on sampling 3, indicating the lack of correct sanitation standard operating procedures10.

Contrary to what was described by other authors1,9,11, isolates from serovars Typhimurium, Give, Cerro and Newport were circumstantial in short periods of time. Cluster IV grouped two S. Typhimurium isolates from carcasses and head meat in abattoir A on the same sampling, probably due to the low capacity of this serovar to form biofilms and persist13. Two clonal strains of serovar Give were also isolated from workers’ hands and carcasses in the mentioned abattoir on two successive samplings (cluster V). Although this serovar has been associated with cattle in the province of Buenos Aires2, its detection in workers’ hands represented a source of contamination in the establishment15.

The results obtained revealed the simultaneous presence of different clones of S. enterica serovars in the same abattoir by XbaI-PFGE, as well as their self-perpetuating capacity. However, these strains should be analyzed using genome sequencing-based methods such as whole genome sequencing12 to obtain more robust conclusions. In the meantime, provincial abattoirs from Argentina should be strictly monitored and, besides promoting GHP, the implementation of an HACCP plan is necessary to meet the zero-tolerance criteria for Salmonella on beef.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This study was undertaken under the Project “The Omics at the service of animal production and food security in the 2030 horizon”, of IGEVET-CONICET, whose support is greatly acknowledged. We thank A. Di Maggio for editing the manuscript.